Surveillance of Healthcare-Associated Infections

Mary Andrus

Teresa C. Horan

Robert P. Gaynes

The findings and conclusions in this chapter have not been formally disseminated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and should not be construed to represent any agency determination or policy.

DEFINITION OF SURVEILLANCE

Surveillance is “the ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of public health practice, closely integrated with the timely dissemination of these data to those who need to know” (1). A healthcare-associated infection (HAI) surveillance system may be sentinel event-based, population-based, or both. A sentinel infection is one that clearly indicates a failure in the hospital’s efforts to prevent HAIs and, in theory, requires individual investigation (2,3). For example, gastroenteritis caused by Salmonella spp. in a patient hospitalized for >3 days should always prompt investigation because it clearly indicates a failure of the hospital’s safeguards. Denominator data usually are not collected in sentinel event-based surveillance. Sentinel event-based surveillance will identify only the most serious problems and should not be the only surveillance system in the hospital. Population-based surveillance (i.e., surveillance of patients with similar risks) requires both a numerator (i.e., HAI) and denominator (i.e., number of patients or days of exposure to the risk). An HAI surveillance program should be accurate, timely, useful, consistent, and practical.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Since the first edition of this book, there has been a great deal of discussion and debate among professionals over the desirability of continuing routine surveillance, argued by some to be too personnel-time-intensive in an era of constrained hospital budgets. As this discussion continues, an account of the development of concepts and techniques of surveillance should be considered. Many of these techniques were developed to meet emerging problems, and the basic concept of surveillance has been found effective in reducing HAI risk. Knowledge of the historical reasons for these developments may help improve the efficiency and effectiveness of surveillance without discarding the well-conceived approaches that remain effective.

The use of surveillance methods to control HAIs dates back at least to the classic work of Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis in Vienna in the 1840s (4). Although the Semmelweis story is best remembered as the first demonstration of person-to-person spread of puerperal sepsis and of the effectiveness of handwashing with an antiseptic solution, an equally important achievement was Semmelweis’ rigorous approach to the collection, analysis, and use of surveillance data. In contrast, the concurrent work of Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes on the same subject in the United States was based primarily on the traditional anecdotal case-study approach of clinical medicine.

Semmelweis’ investigation constitutes an amazingly contemporary example of the effective use of surveillance in addressing a widespread HAI problem. When he assumed the directorship of the obstetric service at the Vienna Lying-in Hospital in 1847, Semmelweis noted that the apparent risk of maternal mortality had been at high levels for >20 years. The eminent clinicians of the day, in fact, considered the risks to be no more than the expected endemic occurrence that could not be influenced. Semmelweis first undertook a retrospective investigation of maternal mortality and set up a prospective surveillance system to monitor the problem and, later, the effects of control measures. The initial results of his retrospective study of annual hospital mortality showed clearly that the maternal mortality level, which he measured by calculating yearly mortality rates, had increased 10-fold following the introduction in the 1820s of the new anatomic school of pathology, which used autopsy as its primary teaching tool. On the basis of the use of ward-specific mortality, Semmelweis calculated that the risk of death on the ward used for teaching medical students was at least four times higher than that on the ward used for teaching midwifery students. After the septic death of his mentor suggested the presence of a transmissible agent, Semmelweis used the findings from his retrospective surveillance study to implicate the practices of the medical students. After observing their daily routines, he surmised that students might be transferring “cadaver particles” from cadavers to the parturient women and that washing hands with a chlorine solution might prevent this transmission. Subsequently, his prospective surveillance data documented a dramatic reduction in maternal mortality immediately following the institution of mandatory handwashing before entering the labor room.

Apparently, due to his abrasive manner, lack of diplomacy, and inability to organize his statistical data into a concise and convincing report, Semmelweis failed to win over his clinical colleagues to his discovery. Within 2 years, he was dismissed from the staff of the hospital, and his successor gradually allowed the strict handwashing measures to decline. In the absence of continuing surveillance, the epidemic promptly resumed and lasted well into the early part of the 20th century, its

severity and means of prevention apparently unappreciated by several more generations of clinicians.

severity and means of prevention apparently unappreciated by several more generations of clinicians.

This story illustrates one of the main impediments to infection prevention and control today: in the absence of carefully collected epidemiologic data and a diplomatic presentation, clinicians, who are oriented almost entirely toward the treatment of individual patients, often fail to appreciate the severity of the HAI pathogen-transmission problem and sometimes resist control measures. It also points out the utility of surveillance in identifying problems and developing and applying control measures. From a methodologic viewpoint, Semmelweis’ efforts encompassed almost all aspects of the modern surveillance approach: retrospective collection of data to confirm the presence of a problem; analysis of the data to localize the risks in time, place, and person; controlled comparisons of high- and low-risk groups to identify risk factors; formulation and application of control measures; and prospective surveillance to monitor the problem, evaluate the implemented control measures, and detect future recurrences. The main shortcoming of his approach was in not diplomatically educating his powerful colleagues with a careful report of his findings.

Despite Semmelweis’ historical model, the modern era of HAI surveillance grew more from mid-20th century experience. The importance of surveillance for disease control in general arose in the effort to control tropical diseases among troops stationed in the Pacific Theater in World War II. At the end of the war, most of the epidemiologists of the “Malaria Control in War Areas Unit” were transferred to a civilian facility to apply their surveillance and control strategies to the control of malaria in the southern United States. Located in Atlanta, near the endemic areas, the unit was first named the Communicable Diseases Center and later became the Centers for Disease Control and then the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Since the large number of reports of malaria indicated the disease to be widespread, a surveillance system was immediately set up to define the extent of the problem. However, as investigators examined each reported case, they found virtually all of the reports had errors in diagnosis. Thus, the mere activity of surveillance “eradicated” the malaria epidemic in the United States.

Because of this and similar successes, when the pandemic of staphylococcal infections swept the nation’s hospitals in the mid-1950s, CDC staff members were quick to apply the concepts of surveillance to the problem (5). When asked to assist in investigating a staphylococcal epidemic in a particular hospital, these early investigators often met strong resistance from clinicians, and hospital administrators convinced that no unusual infection problems were present in their hospitals. In instances when CDC staff members were able to continue the investigations, the collection and reporting of surveillance data regularly changed those attitudes to strong concern over the documented problems and eagerness to apply control measures. These initial investigations thus confirmed a nationwide staphylococcal epidemic and led the CDC to sponsor several national conferences to discuss the problem.

By the early 1980s, some critics were questioning the effectiveness and cost-benefit of routine HAI surveillance although a growing number of hospitals were increasing their surveillance efforts rather than cutting them back (6). Surveillance was, and remains, a time-consuming activity, requiring about 40% to 50% of the time of an infection preventionist (IP) (7).

Several factors have influenced contemporary practices favoring robust surveillance activities in infection prevention and control programs. First, the results of the Study on the Efficacy of Nosocomial Infection Control (SENIC) project strongly substantiated the importance of surveillance along with prevention and control measures to reduce HAI rates and provided the scientific basis for surveillance of HAIs (8). The conclusion was that hospitals that are effective in reducing their HAI rates have an organized, routine, hospital-wide surveillance system. Second, the requirements of the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (TJC, formerly JCAHO) have legitimized the need for personnel to perform surveillance (9,10). Third, the surveillance practices developed in infection control have begun to influence other aspects of the hospital’s quality monitoring and improvement activities (11). The strategies of targeting surveillance to reduce specific endemic problems and monitoring to assess the intervention’s effectiveness were incorporated into TJC’s 1994 infection control standards for accreditation and were applied to hospital quality-assurance programs to reduce noninfectious complications (12).

The increasing pressure to continually improve quality has broadened the use of surveillance to aid in the prevention of HAIs (13). The Institute of Medicine’s Report, To Err is Human, in 2000 helped to focus public attention on the problem of medical errors, including discussions on HAIs as preventable harms (14). Since that report, consumer advocacy groups, legislative bodies, and accreditation organizations have increasingly demanded public reporting of HAIs. These groups argued that heightened transparency of HAI rates would improve the quality of care largely by increasing competition to stimulate hospitals to reduce infections.

GOALS OF SURVEILLANCE

A hospital should have clear goals for doing surveillance. These goals must be reviewed and updated frequently to address new HAI risks in changing patient populations, such as the introduction of new high-risk medical interventions, changing pathogens and their resistance to antibiotics, and other emerging problems. The collection and analysis of surveillance data must be performed in conjunction with prevention strategies. It is vital to identify and state the objectives of surveillance before designing a surveillance program and starting it (15,16).

REDUCING HAI RISK WITHIN A HOSPITAL

The most important goal of surveillance is to reduce the risks of acquiring HAIs. To achieve this goal, specific objectives for surveillance must be defined on the basis of how the data are to be used and the availability of financial and personnel resources for surveillance (15,16,17). The objectives for surveillance can be either outcome- or process-oriented. Outcome objectives are aimed at reducing HAI risk and their associated costs (17). By using comparative HAI data and providing feedback to patient-care personnel, outcome data are useful in demonstrating where gaps in HAI prevention activities exist. Process objectives help to identify the delivery of care problems that can have an effect on patient outcomes. Examples of process measures are observing and evaluating patient-care practices, monitoring equipment and the environment, and providing education. However, these activities are of limited value without clearly

stating the outcome objectives. While HAI surveillance has other legitimate purposes, the ultimate goal is to use process objectives to achieve the outcome objectives: decreases in HAI rates, morbidity, mortality, and cost.

stating the outcome objectives. While HAI surveillance has other legitimate purposes, the ultimate goal is to use process objectives to achieve the outcome objectives: decreases in HAI rates, morbidity, mortality, and cost.

ESTABLISHING ENDEMIC RATES

Surveillance data should be used to quantify the baseline rates of endemic HAIs. This measurement provides hospitals with knowledge of the ongoing HAI risk in hospitalized patients. Most HAIs, perhaps 90% to 95%, are endemic (i.e., not part of recognized outbreaks) (18). Thus, the main purpose of surveillance activities should be to lower the endemic HAI rate rather than identify outbreaks, and many hospital IPs report that their presence on the wards may be sufficient to influence HAI rates (19). However, the mere act of collecting data does not usually influence HAI risk appreciably unless it is linked with a prevention strategy. Otherwise, surveillance is no more than “bean counting,” an expensive exercise without focus that today’s hospitals can ill afford and that IPs will ultimately find dissatisfying.

IDENTIFYING OUTBREAKS

Once endemic HAI rates have been established, IPs and hospital epidemiologists may be able to recognize deviations from the baseline that sometimes indicate infection outbreaks (see Chapter 8). This surveillance benefit must be balanced with the relatively time-consuming task of ongoing data collection because only a small proportion of HAIs, perhaps 5% to 10%, occur in outbreaks (17). Moreover, HAI outbreaks often are brought to the attention of IPs by astute clinicians or laboratory personnel much more quickly than by the analysis of routine HAI surveillance data. This lack of timeliness often limits the use of routine HAI surveillance in identifying outbreaks in a hospital, although the use of data-mining software may address this issue (see Chapter 10).

CONVINCING HOSPITAL PERSONNEL

Convincing hospital personnel to adopt the recommended preventive practices is one of the most difficult tasks of an infection prevention and control program. Familiarity with the scientific literature on hospital epidemiology and infection prevention and control is effective in influencing behavior only if the hospital personnel believe the information is relevant to the specific situation in question. Studies in the literature may not address the many varied situations encountered in a particular hospital. Using information on one’s own hospital to influence personnel is one of the most effective means to address a problem and apply the recommended techniques to prevent HAIs. If surveillance data are analyzed appropriately and presented routinely in a skillful manner, hospital personnel usually come to rely on them for guidance. The feedback of such information is often quite effective in influencing the behavior of healthcare workers to adopt the recommended preventive practices (8). A team approach with IPs working with clinicians from a variety of disciplines is particularly effective (15).

EVALUATING CONTROL MEASURES

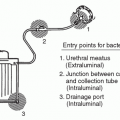

After a problem has been identified through surveillance data and control measures have been instituted, continued surveillance is needed to ensure that the problem is under control. By continual monitoring, some control measures that seemed rational can be shown to be ineffective. For example, the use of daily meatal care to prevent healthcare-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs) seemed appropriate but did not control infection (20). Even after the initial success of control measures, breakdowns in applying them can occur, requiring a constant vigil including the continued collection of surveillance data.

SATISFYING ACCREDITING AND REGULATORY AGENCY SURVEYORS

Satisfying the requirements of accrediting organizations, such as TJC, is a very common use of HAI surveillance data but one of the least justifiable. The collecting of surveillance data merely to satisfy a surveyor who visits a hospital once every 3 years (or occasionally more often) is a largely unproductive use of resources. TJC also changed its requirements to avoid this task-oriented process of collecting data when it altered its standards in 1990. Hospitals are now required to use HAI surveillance in a directed manner to initiate specific interventions designed to lower the risk of HAIs in patients (10). TJC’s Agenda for Change has motivated hospitals to use HAI surveillance for its originally intended purpose: to change the outcome of patient care by reducing HAI risk. More recently, the US Congress has passed legislation that sanctions the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to financially incentivize hospitals if potentially preventable HAIs are reduced (21) (see Chapter 13).

DEFENDING MALPRACTICE CLAIMS

One concern about the collection of HAI surveillance data has been that it would create a record that could be used against the hospital in a malpractice claim related to an HAI. A strong surveillance component in an infection prevention and control program will demonstrate, however, that a hospital is attempting to detect problems rather than conceal them. Additionally, the records of infection control committees are considered privileged in most states and may not be discoverable in civil court proceedings. Therefore, surveillance is often helpful in defending against malpractice claims, and it is rarely, if ever, a hindrance.

COMPARING HOSPITALS’ HAI RATES

Traditionally, HAI surveillance has been recommended solely for gaining an understanding of and reducing HAI rates within individual hospitals. The idea of comparing HAI rates among hospitals, though often suggested by administrators and quality-assurance supervisors, has generally been discouraged by IPs and hospital epidemiologists. They argue that the mix of intrinsic HAI risk of the patients in different hospitals renders differences among the hospital rates virtually uninterpretable. Studies performed by CDC, however, have suggested that interhospital comparisons can be useful in reducing HAI risk (22), if the rates are specific to a particular site of HAI (e.g., UTI) and control for variations in the distributions of the major risk factor(s) for that type of infection (e.g., duration of indwelling urinary catheterization). Conversely, using a single number to express a hospital’s overall HAI rate falls short as

a valid measure largely because suitable overall risk adjusters for infections of all types are lacking (23,24,25,26). Therefore, a hospital’s overall HAI rate should not be used for interhospital comparisons.

a valid measure largely because suitable overall risk adjusters for infections of all types are lacking (23,24,25,26). Therefore, a hospital’s overall HAI rate should not be used for interhospital comparisons.

PUBLIC REPORTING OF HAI DATA

Many state and national initiatives to mandate or induce healthcare organizations to publicly disclose information regarding institutional and physician performance are underway (see Chapter 47). Mandatory public reporting of healthcare performance is intended to enable stakeholders, including consumers, to make more informed decisions about healthcare choices, and has taken several forms such as report cards and honor rolls. In an effort to provide guidance and to establish more uniformity, the CDC, through the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), issued a guidance document on public reporting of HAIs in 2005, which included both outcome and process measures (27). As of January 2012, 32 states in the United States require hospitals to publicly report their HAI rates (28,29). Most states (28) and the District of Columbia use or will use the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) for HAI reporting mandates. In addition, CMS’ Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Program requires the use of NHSN for hospitals in that program to report central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLA-BSI), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CA-UTI), and surgical site infections (SSI) for two operative procedure categories (30). These data are or will be publicly reported on CMS’ Hospital Compare website (31).

The accuracy of data reported via mandate has been questioned by several attempts at validating these data (32,33,34,35,36). The problems in accuracy were sometimes based on inaccurate denominator data but most often were due to underreporting of infections, largely because of the variability and subjectivity in applying surveillance definitions. Efforts to create accurate objective measures of HAI, including electronic algorithms [37,38,39,40] that will be most useful for public reporting of HAI data, should ensure that such measures of HAI evaluate the same event, no matter where the care is delivered or who collects the information. In addition, ideally, every hospital, healthcare provider, or payer should be able to implement the measures relevant to the care provided or compensated.

Presently, the evidence on the merits and limitations of using an HAI public reporting system as a means to reduce HAIs is insufficient. The CDC/HICPAC guidance was intended to assist policymakers, program planners, consumer advocacy organizations, and others tasked with designing and implementing HAI public reporting systems. The challenges for meaningful interpretation of publicly reported HAI data include accuracy in identifying HAIs, risk adjustment to account for the varying degrees of risk among the sampled patient population, and the method of expression of the HAI data. Some investigators have recommended that efforts should be directed instead to creating acceptably accurate, objective measures of quality of care, such as process and/or surrogate measures that all healthcare facilities can use (41). Process measures can be useful when their link to beneficial or adverse outcomes is well established. For example, the appropriate delivery of perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis is a case in point of a process measure that emerged from decades of research (42). Surrogate measures are objective indicators of readily ascertained events that are sufficiently correlated with HAIs to provide useful information about the actual institutional HAI rate (43). For example, the SSI rates following coronary artery bypass graft, Cesarean section, or breast surgery appear to correlate closely with the proportion of patients who receive extended courses of inpatient antibiotics and are useful indicators of a hospital’s SSI outcomes for those procedures (44).

METHODS OF SURVEILLANCE

PLANNING FOR SURVEILLANCE

Once the goals of surveillance have been identified, the hospital should develop a formal, written surveillance plan, detailing how these goals will be met. The plan should include the outcomes and/or care processes to be surveyed; the frequency and duration of the monitoring; methods of surveillance to be undertaken, including definitions; metrics and their calculations; and dissemination strategies (15). Most acute care facilities (e.g., hospitals, long-term acute care facilities) in the United States perform prospective incidence surveillance of endemic infections. Depending on the goals, as well as the size of the facility, complexity of the patients, and resources available for surveillance, a combination of targeted and facility-wide surveillance will be included in the surveillance plan. The methods will focus on a combination of outcome and process measures and will include active case finding.

PROSPECTIVE INCIDENCE SURVEILLANCE