Surgical Technique

Marc S. Zimbler

When analyzing facial soft tissue skin defects certain considerations are important, even before examining the defect itself. First and foremost, the reconstructive surgeon must be comfortable with the tumor extirpation itself. This is essential in cases where the reconstruction will involve the rearrangement of local tissue. Otherwise, concealing residual tumor can have devastating consequences. For many basal and squamous skin cancers of the face this means removing the lesion with Mohs micrographic surgery. In cases of melanoma, reconstruction should be delayed until permanent section analysis of surgical margins are completed. Other considerations prior to examining the defect include the patients’ skin thickness, skin color and texture, and surrounding solar damage. Age and resultant skin laxity are also important when determining how much tissue advancement can be achieved and how long incisions should be made. Many skin cancer patients have had prior malignancies or recurrences, and scar tissue in the immediate or adjacent regions can influence reconstructive choices. Also, prior elective operations such as rhinoplasty or rhytidectomy can influence the surgeon’s decision making. Consideration of comorbidities is also important. Many elderly skin cancer patients are on anticoagulants, have a history of diabetes, may not tolerate general anesthesia, or lack the ability to care for complex postoperative wounds. Cancer monitoring is always a major concern with more invasive tumors or recurrences. In many specific cases, a simple reconstruction is chosen initially, and then a more complex staged procedure can be performed once sufficient cancer monitoring has been obtained. The patient’s own expectations are also essential to the surgeon’s planning. For instance, does the patient require a complex staged surgery if his/her own aesthetic satisfaction is achieved with a simpler option. Many times the surgeon’s level of aesthetic may not correlate with that of the patient. This is often a subtle distinction.

After considering these issues, it is now time to examine the defect. When examining the defect, several factors are determined initially before a reconstructive is designed. Relative to the defect three factors are essential—defect location, size, and depth. Ideally, each layer of absent tissue should be replaced by like tissue. When possible, the cutaneous defect should be closed with skin of similar thickness, color, and texture to that missing. Missing cartilage should be replaced by appropriately

positioned, contoured, and sculpted cartilage. Facial location is critical because defects of the nose may be treated differently than others in which adjacent lax skin is abundant. Defect size is particularly important in determining whether a flap or skin graft is preferable. Depth of the defect is also considered because some are very superficial and can be treated by allowing secondary intention healing. On the other hand, deeper defects with exposed cartilage or bone may require flap coverage.

positioned, contoured, and sculpted cartilage. Facial location is critical because defects of the nose may be treated differently than others in which adjacent lax skin is abundant. Defect size is particularly important in determining whether a flap or skin graft is preferable. Depth of the defect is also considered because some are very superficial and can be treated by allowing secondary intention healing. On the other hand, deeper defects with exposed cartilage or bone may require flap coverage.

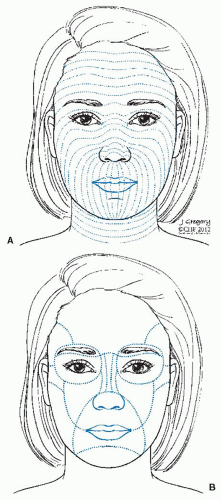

The location of the defect in relation to relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) and facial aesthetic subunits (Fig. 23-36A,B) is also an essential consideration in planning reconstruction. Scar orientation parallel to RSTLs or those camouflaged within facial aesthetic subunits create an optimal environment for wound healing and eventual scar formation. The importance of reconstructions utilizing these two key factors cannot be over emphasized.

Generically speaking, options for repair include healing by second intention, primary closure, skin graft, and skin flapslocal, regional, or distal. Although most publications on reconstructive surgery concentrate on flap design, one should not underestimate primary closure as a viable source in the appropriately chosen regions. Key considerations to this method are wide subcutaneous undermining, defect size, and location. Primary closure should be the first consideration for reconstruction of a surgical defect, and especially in those patients in whom there is an abundance of adjacent lax tissue, it is often the method of choice. Many cheek and forehead defects can be closed primarily as long as they do not cause distortion of adjacent structures such as the lower eyelid and eyebrow. Key to this determination is defect size, proximity to the structure of concern, as well as laxity of the skin. Primary closure should be oriented parallel to relaxed skin tension lines or hidden within facial aesthetic subunits whenever possible. Except for small midline defects, primary closure is seldom possible on the distal nose. The size and midline location is critical to the outcome so as not to cause unilateral nasal distortion.

Skin grafts are also insufficiently discussed in the literature, even though they can play an essential role. Skin grafts on the face should be full thickness when possible. Compared with split thickness grafts, they have the advantage of creating a better color and texture match. They also create less contour irregularities, resist contraction, do not require special equipment to harvest, and are associated with less donor site morbidity. Typical donor sites for full thickness skin include postauricular, preauricular, and supraclavicular areas. Less commonly used sites are the upper forehead, upper eyelid, and nasolabial fold. When determining which site would be most appropriate to reconstruct, the surgeon must examine the defect for size, skin thickness, skin texture, and depth. Postauricular skin, which is often a first choice, is limited by amount of skin for harvest and thin nature, and often it is light colored. Preauricular skin is an excellent choice for thickness and color match, but is also limited by defect size. For larger defects, the supraclavicular region is excellent; however, skin match for the face may be suboptimal. When harvesting skin graft donor sites around the ear, prior facelift scarring can limit tissue availability. Adequate fat trimming from the skin undersurface and postoperative bolster placement are important in helping to maintain graft survivability after placement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree