Surgical Technique

Ramon M. Esclamado

Liana Puscas

INTRODUCTION

Contemporary reconstruction of ablative defects of hypopharyngeal carcinoma remains clinically challenging. Successful and appropriate reconstruction requires a thoughtful analysis of many factors that will ultimately impact the choice of the reconstructive technique employed. Careful consideration should be given to reconstructive goals, oncologic outcomes, patient related factors, and comorbidities, the extent of the surgical defect, as well as the expertise and preferences of the reconstructive surgeon. Ideally, the reconstructive team will have available the entire armamentarium of reconstructive options and will utilize the technique that is best suited for the patient, that optimizes function, while minimizing both short-term morbidity, long-term disability, and expense.

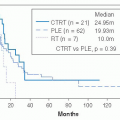

The reconstructive goals are straightforward but elusive: to restore continuity of the alimentary tract so that a patient is able to eat a normal diet, while preserving laryngeal voice or restoring alaryngeal speech. Oncologic factors are essential to consider. Although primary and salvage hypopharyngectomy have comparable locoregional control rates and survival, overall and disease-specific survival remains poor.1 Therefore, reconstruction should be single stage, have a low rate of fistula and delayed wound healing, allow for early resumption of deglutition and voice restoration, and have a low rate of delayed strictures, particularly if postoperative radiation is required. Since surgical ablation nearly always includes unilateral or bilateral neck dissection, the choice of reconstructive technique will in part depend upon availability and location of recipient vessels for free tissue transfer and should consider minimizing shoulder disability, particularly if the spinal accessory nerve has been sacrificed.

Patient-related factors and comorbidities must be recognized and considered to optimize outcomes.2 In this era of concurrent chemoradiation therapy (CRT), iatrogenic hypothyroidism occurs in 48% of patients as early as 4 weeks posttreatment.3 These patients can also be nutritionally or metabolically debilitated from alcohol and tobacco abuse, tumor burden and odynophagia, or from CRT. When primary surgery and reconstruction is contemplated, nutrition should be optimized; in the salvage setting, a preoperative TSH should be obtained. Diabetics should be carefully selected and managed in the perioperative period. Preoperative radiation, malnutrition, diabetes, and unrecognized hypothyroidism are known to increase fistula rates and delay wound healing.4,5 Many patients have COPD, and consideration should be given to choosing donor sites that are not intra-abdominal to minimize postoperative pulmonary complications.

The extent of the surgical defect is a primary determinant of the selected reconstructive option. Defect classifications have been proposed,6 but not universally adopted. The first

consideration is whether all or part of the larynx has been preserved. Reconstruction will require, thin, pliable tissue that can be contoured so as not to obstruct the airway and suspended with little downward traction to preserve laryngeal elevation. If total laryngectomy is performed, the second consideration is whether the pharyngectomy is total, requiring a completely tubed reconstruction, or partial, which would allow a “patch” graft. The superior extent of the defect must also be evaluated because there is a caliber mismatch between the base of tongue/oropharyngeal defect compared with the esophageal lumen that is magnified when resection includes portions of the tongue or oropharyngectomy. Finally, one must consider if the inferior anastomosis can be performed in the neck. Hypopharyngeal cancer can have significant submucosal spread, and historically total esophagectomy was regularly used to obtain a 4 cm or greater inferior margin, which precluded a cervical anastomosis. However, it has been shown that a 2-cm inferior esophageal margin is adequate and facilitates utilizing less morbid reconstructive techniques.7,8

consideration is whether all or part of the larynx has been preserved. Reconstruction will require, thin, pliable tissue that can be contoured so as not to obstruct the airway and suspended with little downward traction to preserve laryngeal elevation. If total laryngectomy is performed, the second consideration is whether the pharyngectomy is total, requiring a completely tubed reconstruction, or partial, which would allow a “patch” graft. The superior extent of the defect must also be evaluated because there is a caliber mismatch between the base of tongue/oropharyngeal defect compared with the esophageal lumen that is magnified when resection includes portions of the tongue or oropharyngectomy. Finally, one must consider if the inferior anastomosis can be performed in the neck. Hypopharyngeal cancer can have significant submucosal spread, and historically total esophagectomy was regularly used to obtain a 4 cm or greater inferior margin, which precluded a cervical anastomosis. However, it has been shown that a 2-cm inferior esophageal margin is adequate and facilitates utilizing less morbid reconstructive techniques.7,8

The experience and preferences of the reconstructive surgeon or team, and the availability of facilities to appropriately care for these patients cannot be overlooked. The literature abounds with studies espousing the superiority of one reconstructive technique over another, and there are benefits of expertise gained in performing a specific reconstructive technique repetitively so that errors in technique or judgment are minimized. Ideally, the reconstructive decisions take into account all of the above-mentioned factors, so that the reconstructive method chosen is best suited for the particular patient.

RECONSTRUCTIVE OPTIONS

A variety of reconstructive options are available. The pertinent surgical anatomy, blood supply, harvesting techniques, and donor site management and complications have been well described and are beyond the scope of this chapter. The myriad of the most commonly used flaps are listed in Table 19.8, and it is important to understand the broad principles as to their advantages and disadvantages.

Regional flaps are either fasciocutaneous or myocutaneous. They are readily harvested, do not require microvascular expertise, and are fairly reliable. The muscle pedicle of myocutaneous flaps can provide additional carotid protection. They can have limited reach and arc of rotation and can be bulky and not as pliable in a three-dimensional reconstruction. The bulk and weight of the flap and pedicle could cause undue wound tension and increase the risk of wound complications.9 When the skin paddle is extended beyond the normal vascular territory, there can be a partial flap necrosis. Fasciocutaneous flaps usually require a two-stage reconstruction to close a pharyngectomy defect, but are very useful in creating a controlled fistula to exteriorize a persistent fistula in an infected neck.

TABLE 19.8 Reconstructive Options for Hypopharyngeal Reconstruction | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Revascularized (free) flaps are generally excellent options, although microvascular expertise is required, and operative time can be prolonged, but minimized with a two-team approach. Adequate recipient vessels are essential, and flap survival rates exceed 95% to 98%. A postoperative fistula with infected saliva draining over the vascular pedicle can cause late thrombosis, which is rare in pedicled flaps. The lack of a fixed pedicle allows three-dimensional positioning to minimize tension on the suture lines, and wound tension from downward traction can be minimized. The variety of donor sites allows selection of texture, bulk, and flap size to optimally reconstruct the defect.

DEFECT RECONSTRUCTION AND RESULTS

As previously mentioned, the extent of the surgical defect is the primary determinant of the selected reconstructive option. Therefore, we will approach reconstruction of hypopharyngeal defects primarily by analyzing the defect, defining reconstructive goals, and looking at the advantages and outcomes of the most commonly used reconstructive options.

The Partial Pharyngectomy Defect with an Intact or Partially Resected Larynx

The more common defect is a partial pharyngectomy defect with an intact larynx. A limited lateral wall defect can be closed primarily or with a thin pectoralis myocutaneous (PMC) flap. Since most defects involve the posterior hypopharyngeal wall with or without the lateral wall of the piriform sinus(es), the surgical goal is to provide thin pliable tissue. When partially tubed, the reconstruction should not obstruct the airway nor impair laryngeal elevation. The radial forearm free flap (RFFF) is ideal in this setting, since it is thin, pliable, and very reliable.10 The disadvantages are that the donor site generally requires skin grafting or alloderm to close, the skin is nonsecretory, the flap cannot be used in the absence of an intact palmar arch, and if the patient is unwilling to accept the donor-site cosmetic result. Alternatives include the lateral arm11 or the anterolateral thigh (ALT) fasciocutaneous free flaps.12,13 Both of these flaps allow primary closure of the donor site, but can be quite thick and bulky, so the donor site must be carefully evaluated prior to its use. The free jejunal patch graft is a viable alternative and is the preferred option in many centers. It has the theoretic advantage of being self-lubricating, and both fistula and stricture rates are reportedly low when compared with RFFF. It does require a laparotomy, and there is the potential risk of aspiration of jejunal secretion. In a recent series of 43 patients, the flap success rate was 95%, the fistula rate was 11%, which all healed with conservative treatment, and all patients were tracheotomy independent. There were no instances of pneumonia from aspiration of jejunal secretions, and 95% of patients were eating and G-tube independent, usually within 2 weeks postoperatively.14

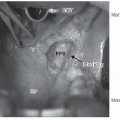

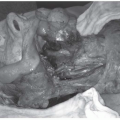

A partial pharyngectomy defect with a partial laryngectomy defect is more challenging. Usually, the hemilarynx and lateral wall of the pyriform sinus are absent with an intact cricoid arch. The reconstructive goals require restoration of glottic closure, and sensation to optimize airway protection, create an adequate airway, and preserve swallowing. Instinctively, one would want to recreate structure and restore the “volume” of the hypopharynx. However, restoring the natural contour of the hypopharynx with an insensate, adynamic flap may not be a good functional restoration when the hemilarynx is also reconstructed. One should consider

insetting enough soft tissue to restore continuity of the hypopharynx so that tension is minimized to facilitate wound healing. However, the reconstruction should “obliterate” the involved lateral piriform wall so that the food bolus will preferentially be diverted to the normal, sensate, and contractile pharyngeal wall. Swallowing can then be facilitated with a “chin tuck” to the involved side to further open the normal side. Kim et al.15 recently reported a series of 31 patients reconstructed with a RFFF for a vertical hemipharyngolaryngectomy for hypopharyngeal carcinoma. The palmaris longus tendon was included to reconstruct the glottis, and in 23 patients, the flap underwent sensory reinnervation to the superior laryngeal nerve. Eighty-eight percent of patients were able to meet all their nutritional needs orally, 2 patients (6%) developed glottic stenosis, marginal flap necrosis was seen in 2 patients (6%) that resulted in fistulas, and 88% of patients were eventually decannulated. If these results can be duplicated, the opportunity will arise for more patients to undergo laryngeal preservation procedures in selected hypopharyngeal cancers because the laryngeal defect can be safely and functionally reconstructed.

insetting enough soft tissue to restore continuity of the hypopharynx so that tension is minimized to facilitate wound healing. However, the reconstruction should “obliterate” the involved lateral piriform wall so that the food bolus will preferentially be diverted to the normal, sensate, and contractile pharyngeal wall. Swallowing can then be facilitated with a “chin tuck” to the involved side to further open the normal side. Kim et al.15 recently reported a series of 31 patients reconstructed with a RFFF for a vertical hemipharyngolaryngectomy for hypopharyngeal carcinoma. The palmaris longus tendon was included to reconstruct the glottis, and in 23 patients, the flap underwent sensory reinnervation to the superior laryngeal nerve. Eighty-eight percent of patients were able to meet all their nutritional needs orally, 2 patients (6%) developed glottic stenosis, marginal flap necrosis was seen in 2 patients (6%) that resulted in fistulas, and 88% of patients were eventually decannulated. If these results can be duplicated, the opportunity will arise for more patients to undergo laryngeal preservation procedures in selected hypopharyngeal cancers because the laryngeal defect can be safely and functionally reconstructed.

The Total Laryngectomy with Subtotal Pharyngectomy Defect

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree