General Principles

Multiorgan resections follow the general principles of all oncological surgery. The patient must be operable, which means that all co-morbidities (cardiopulmonary, renal, etc) must be carefully assessed to determine the true operative risk. Distant metastases must be carefully ruled out by appropriate investigations. Complete local control of the tumor must be achieved. To obtain clear margins a rim of healthy tissue has to be resected with the tumor. Other prerequisites include systematic lymph node dissection, salvaging the blood supply to adjacent structures, the preservation of important nerves, the maintenance of adequate function of vital structures as well the preservation of their pathway of drainage (such as the ureter, for example). As for all major resectional surgery with curative intent, the projected postoperative quality of life is of paramount importance in determining the indication for surgery.1–6 The impact of the surgery must be carefully and very openly discussed with the patient and it is essential to take into account the patient’s perception of adequate quality of life and not to impose on the patient our own views on the subject.

It is not always easy to reconcile these ideals with multivisceral resections. The local control, the respect of the blood supply to adjacent structures, and the maintenance of the patient’s quality of life are essential.7,8 So to justify surgery the prognosis must be substantially better than what palliative surgery or chemotherapy and radiotherapy (either as isolated modalities or in combination) can offer. It is also important to recognize when palliative care (as a sole treatment modality) is the best option for the patient. Finally, the benefits of the surgery have to well outweigh the risks-a patient who dies following surgery cannot be cured.

There is no place for palliative multiorgan resections. To be effective palliation requires low morbidity and quick, uneventful recovery so that the patient can either undergo further therapy or have the best quality of life back as quickly as possible. The risks and recovery times of this type of extensive surgery are only justifiable in the context of curative intent.9

The philosophy of the resection itself follows on logically from these principles. The first and most important step of the operation is the determination of resectability before committing to it. The entire body cavity (chest or abdomen) is carefully inspected for signs of unexpected distant spread. Any areas of concern are biopsied and frozen section is performed. Nothing irreversible is done until these results are available. Any lymph node stations that would determine resectability are dissected out and again any areas of concern are sent for frozen section. Finally, the key areas of concern regarding technical resectability are dissected until the surgeon is sure that a complete resection will be achieved. This is when and only when the point of no return should be reached, which means that irreversible steps will be taken. Beyond this point the surgeon is committed to proceed with resection. Up to this point it is possible to choose to perform a much lesser, purely palliative procedure, or indeed to back out completely. The decision to proceed or to withdraw must always be a cold, clinical decision based on the probability for cure and on the expected quality of life, taking into account the patient’s wishes as ascertained preoperatively. Implicit in the old-fashioned “it’s his/her only chance” heroic attempt to resect the tumor at any cost is the very real ethical issue: is it licit to submit say 97 patients to a totally useless and dangerous operation (which is the case for all patients who are not cured) so that three can benefit (i. e., be cured)? The reader will please note that we have not introduced the difficult “cost per quality of life year gained” issue to this debate.

So, in reality, there are only a very few, very highly selected patients who actually truly qualify for this type of resection and it is of paramount importance to select patients rigorously and scrupulously and to be prepared to perform a lesser operation or to back out when adverse prognostic indicators are found during the initial evaluation phase of the operation. These issues must be fairly and openly discussed with the patient and his/her family prior to surgery as part of the consent process.

The “En Bloc” Resection

The “En Bloc” Resection

Any thoracic or abdominal tumor involving more than one organ must be resected en bloc with the surrounding involved structures.10 This concept of en bloc resection is a constant theme throughout this book and a tenet common to all of its authors. Implicit in the term is the fact that there is only one operative specimen for the pathologist that contains all of the resected structures together. It is important to clearly identify all important structures and resection margins as well as any area of concern regarding tumor proximity so that the pathologist can take appropriate specimens. It is often very useful to go down to pathology immediately after surgery and to go over these complex specimens with the pathologist to help orientate the specimen for him/her and clarify areas of concern. During the operation itself it is important that frozen sections be clearly identified and if there are concerns about margins these areas should be marked with metal clips to help the radiotherapist to target these areas if postoperative radiotherapy would be an option.

These are very challenging operations from a purely technical point of view and require perfect knowledge of the surgical anatomy of the region of interest, including the usual and variant anatomy of neighboring blood vessels and nerves. Adhesions to surrounding structures represent a particular challenge. Obviously it is desirable to take down purely inflammatory adhesions at a distance from the tumor so as to avoid unnecessarily wide excisions, but it is equally of paramount importance not to breach the tumor during the dissection with the attendant risk of intracavitary seeding of the tumor and wound tumor implants.11,12 This risk is not negligible with carcinomas and is considerable with sarcomas. If an inadvertent tumor breach does occur careful consideration should be given to washing out the body cavity with cytotoxic agents or even to proceed with formal intracavitary chemotherapy. As to tumor margins many surgeons prefer to rely entirely on respecting a clear macroscopic margin of healthy tissue around the tumor and deliberately avoid extensive frozen section examination of margins. If there are areas of adhesion these should be dealt with at a distance rather than risking breaching the tumor to obtain histologic confirmation by frozen section. Frozen sections are only justified at key “make or break” points during the explorative phase of the operation to decide if the tumor is technically resectable. If positive they imply retreat.

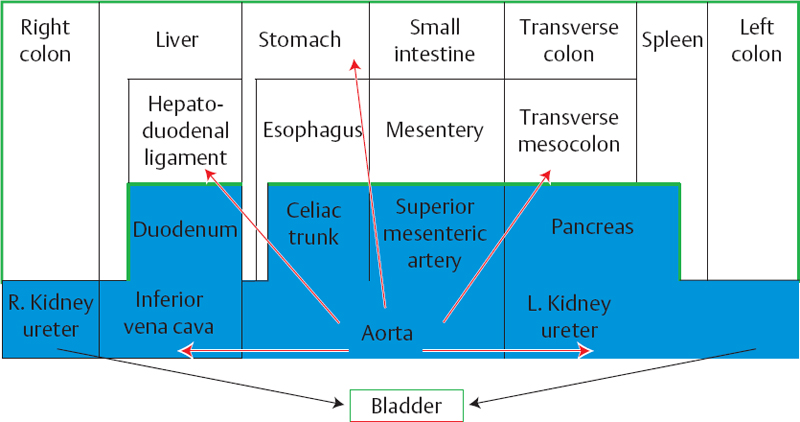

Fig. 2.1 The abdominal organs are schematically represented. The anterior organs are mobile (small intestine, transverse colon) or can be mobilized if they have a contact with the retroperitoneum (ascending colon, liver, esophagus, stomach, spleen, descending colon). The retroperitoneal organs (duodenum, pancreas, major vessels are less easily mobilized). Green line: peritoneum. Blue rectangles: retroperitoneal organs.

From Front to Back

From Front to Back

The preoperative CT and MRI can be very useful to determine if the tumor is in contact with or invades the abdominal wall, especially in the area of the planned incision. If there has been no prior surgery the incision must avoid areas of tumor invasion. If there has been a previous operation it is customary to widely excise the full thickness of the previous incision.

Upon entering the abdomen, once the general inspection and any other distant dissection have been performed the tumor is usually approached from front to back. It is useful to consider the abdominal organs as being disposed in layers (Fig. 2.1). The most anterior layer, made up of the liver, stomach, small bowel, transverse colon, and spleen are mobile or readily mobilizable. The viscera are much more fixed and less readily mobilized as one gets further back in the abdomen. Moreover, towards the posterior peritoneum the organs are much closer to the main blood supply to the abdominal contents such as the celiac axis and the superior mesenteric artery as well as to the great veins and the central lymphatics. Thus, during a multivisceral resection the anterior organs are freed and prepared first, leaving them attached to the deeper organs. The surgeon can then progressively work around them, moving them side to side or up and down so as to free up the more posterior elements last.

The “Secondary” Organ

The “Secondary” Organ

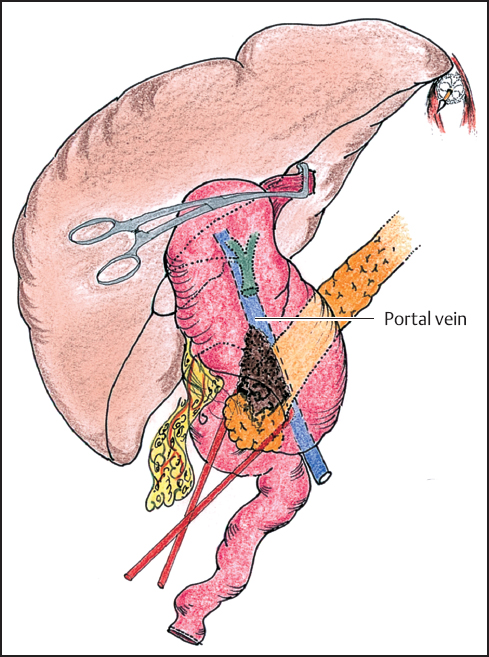

Multivisceral resections have two distinct components, even if an en bloc resection is always performed. The first is the resection of the organ in which the tumor originates. This will be done according to the usual principles guiding the resection of this organ for malignancy. The resection will deviate from this normal course in the area of involvement of the “secondary” organ. At the point where this interferes with the classic resection of the primary organ the dissection of the primary organ will stop to allow the secondary organ to be prepared. This will be done in the customary manner. Then the resection of the primary organ will resume. The operative strategy will of course need to include the reconstruction of all interrupted elements. An example is a tumor of the pancreas infiltrating the posterior wall of the stomach. The operation starts as a classic Whipple’s procedure. After removing the gallbladder and performing a cholangiography, the hepatoduodenal ligament is dissected out separating the common bile duct, the hepatic artery, and taking up the gastroduodenal artery on a vessel loop. The portal vein is found and dissected free of the posterior aspect of the pancreas along with the terminal portion of the mesenteric vein. The duodenum is then freed up widely from the retroperitoneum then the right part of the gastrocolic ligament is picked up allowing the superior mesenteric vein to be dissected out from below the pancreas until the previous dissection from above is met. The first loop of jejunum is divided with a stapler and the ligament of Treitz is taken down allowing the proximal small bowel to pass under the mesentery. The gastroduodenal artery is divided as is the distal common bile duct. Normally the next step would be to divide the proximal duodenum with a stapler. However, now it is time to resect the “secondary” organ-namely the stomach. The gastrocolic ligament is taken down, the left gastric vessels are dissected at their origin and divided. The short gastric vessels are also divided and if a total gastrectomy is to be performed the distal esophagus is dissected circumferentially and will be progressively divided as a Prolene purse-string suture is placed allowing the anvil of an EEA stapler to be placed into the distal esophagus. If a subtotal gastrectomy is planned then the short gastric vessels are spared and the proximal stomach is divided with a stapler. The stomach is now completely free, but remains attached to the pancreas in the area of tumor invasion which has not been touched so as to in no way compromise the completeness of the resection (Fig. 2.2). At this point the pancreatectomy can proceed with the division of the pancreas through the isthmus. Then the dissection of the posterior aspect of the pancreas from the portal vein can be completed and the uncinate process can be dissected out taking down the retroportal lamina in the retroperitoneum. The operative specimen is now free and can be handed off. The reconstruction can now proceed, reestablishing intestinal continuity with either the distal esophagus or the stomach remnant.

Fig. 2.2 The first steps of the duodenopancreatectomy are completed: the hepatoduodenal ligament is dissected, the duodenum is Kocherized, the venous axis is prepared, the choledochus and first jejunal loop are divided. The greater curvature is now reflected on the right and the esophagus is divided. The further steps of the duodenopancreatectomy are then processed with the section of the isthmus of the pancreas.

The Point of No Return

The Point of No Return

In all complex operations there is a point beyond which the resection must proceed. It is important to ensure that no irreversible steps are taken until the surgeon is sure that it will be technically possible to resect the tumor. Mobilization of the omentum, the duodenum, or even dividing the intestine with a stapler are all examples of reversible steps in the evaluation of the tumor. However, once the blood supply to an organ is interrupted or that a solid organ itself is divided the point of no return has been breached.

Once the point of no return has passed it is essential to always bear in mind what must stay behind and to ensure that the blood vessels to these structures remain intact. For example, when proceeding with a combined gastrectomy-splenopancreatectomy the hepatic artery must be preserved with its origin at the celiac trunk. However, the left gastric and splenic arteries will be divided.

Centripetal Resection

Centripetal Resection

Centripetal resection is a variant of the concept of front to back surgery. It is most commonly used in the superior part of the abdomen. It encompasses not only the resection of the organs which are involved by the tumor but also the systematic nodal dissection of the appropriate lymphatics which remain in continuity with the operative specimen. Thus, the primary organ and the secondary organ are first freed up anteriorly, then from above, below, and on both sides. The posterior aspect with the lymphatics is dissected last. The dissection becomes a sort of funnel. If we take the example of a combined gastrectomy-distal pancreatectomy-splenectomy for a stomach tumor invading the pancreas and/or spleen, the stomach is first prepared together with the omentum. The proximal duodenum is divided with a stapler. The spleen is freed from the diaphragm and retroperitoneum and mobilized to the right. This delivers the tail of the pancreas which is divided. The abdominal esophagus is dissected circumferentially and divided. The work at the mouth of the funnel is now done. Further dissection will follow the funnel down to the depths of the abdomen encompassing the nodal dissection. This usually starts at the hepatoduodenal ligament taking all the nodes off of the hepatic artery then along the top of the pancreas to the celiac trunk. The same dissection is then performed from left to right from the hilum of the spleen back to the celiac trunk. Only then will the left gastric and splenic vessels be divided. When this has been done the operative specimen will be free to be handed off. It will include in one specimen the stomach, distal pancreas, spleen, and the nodes draining all of these organs.

Lymphatic Drainage

Lymphatic Drainage

The role of nodal dissection in the staging of abdominal cancer is well established.13–16 This has direct prognostic implications and can influence subsequent management decisions. It is obviously of the same importance in multiorgan resections. The principle nodal dissection will be that of the primary organ.

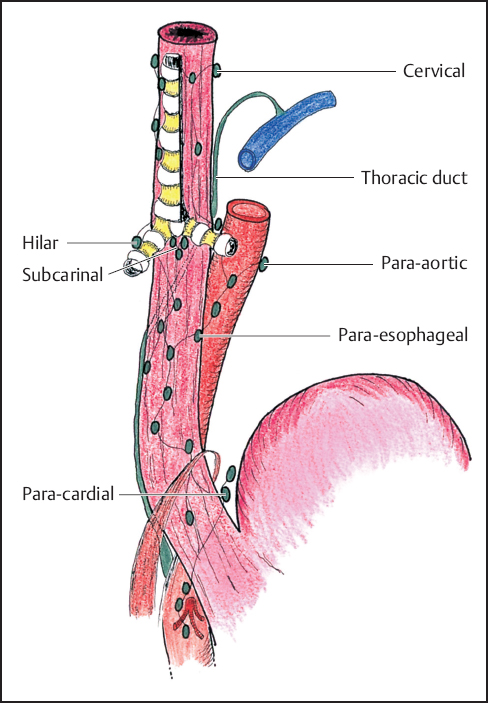

Esophagus

The lymphatic drainage of the esophagus is complex, segmental, and interconnected. It includes the lower cervical, paratracheal, hilar, subcarinal, paraesophageal, paraaortic, paracardial, and celiac nodes (Fig. 2.3).17,18

Fig. 2.3 Diagram of the lymph nodes draining the esophagus.

Stomach

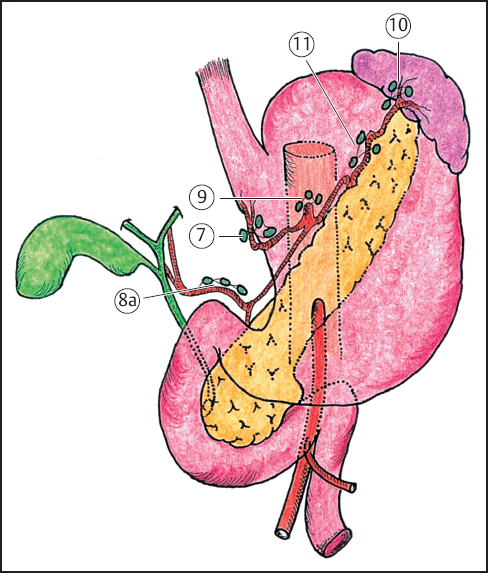

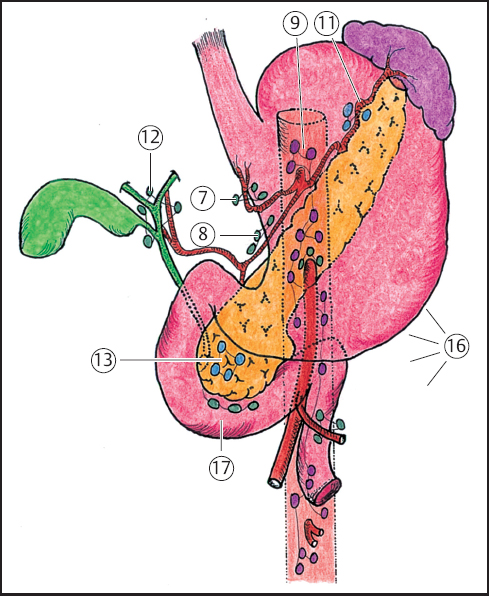

The Japanese Society for Research of Gastric Cancer has defined the different nodal territories for the stomach.19 There are four concentric areas of nodal drainage.20 The N1 nodes are closestto the stomach. They are labeled as follows: stations 1-right paracardial; 2-left paracardial; 3-lesser curvature; 4-greater curvature; 5-supra-pyloric; 6-infrapyloric (Fig. 2.4a). A D1 resection will remove all of these nodes.

The N2 nodes are the second ring of nodes. They are around the celiac trunk and the splenic vessels. They are defined as: stations 7-left gastric artery; 8a-above the common hepatic artery, 9-celiac trunk; 10-hilum of the spleen; 11 -splenic artery (Fig. 2.4b). The resection of these nodes constitutes a D2 resection. This is the subject of some controversy.21,22 It is recommended by most Japanese and German surgeons.23–26

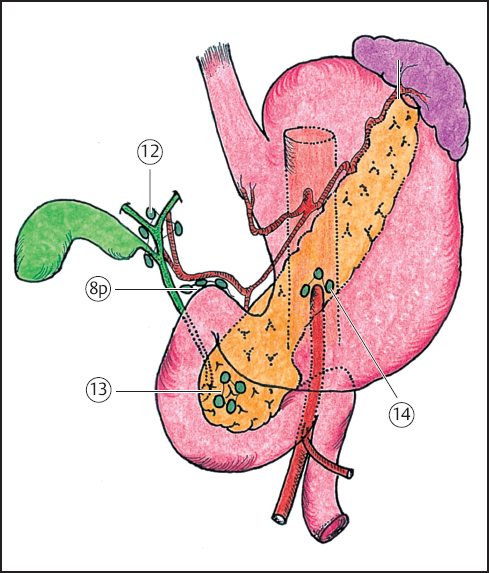

The N3 nodes are deeper or further from the stomach. They are respectively: stations 8p-behind the common hepatic artery; 12-hilum of the liver; 13-retro-pancreatic; 14-root of the mesentery (Fig. 2.4c). The Japanese surgeons are the main proponents of the resection of N3 nodes.27–29

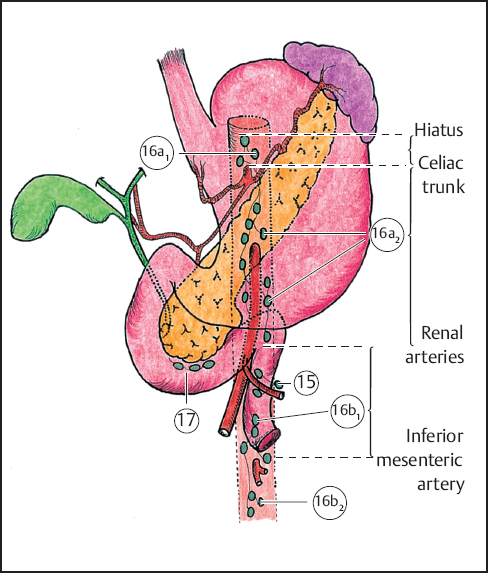

The N4 nodes make up the outside ring. They are respectively: stations 15-middle colic artery; 16 (a,b,c,d)-pre- and paraaortic (Fig. 2.4d). They are the last nodes prior to drainage into the major lymphatics. The Japanese surgeons are practically the only ones who resect these nodes.30–32

Fig. 2.4a Diagram of the N1 lymph nodes draining the stomach.

Fig. 2.4b Diagram of the N2 lymph nodes.

Fig. 2.4c Diagram of the N3 lymph nodes.

Fig. 2.4d Diagram of the N4 lymph nodes.

Pancreas

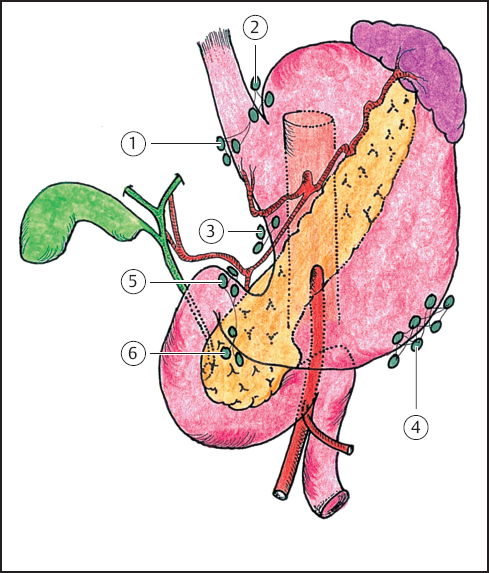

The lymphatic drainage from the head and body of the pancreas is towards the celiac trunk nodes. The head of the pancreas drains to stations 7, 8, 9,11,12,13, 14, 15, and 17 (anterior pancreaticoduodenal nodes) (Fig. 2.5).33–35 The lymphatic drainage seems to follow the embryological development of the organ36: the ventral bud gives rise to the unciform process as well as to the retromesenteric and retroportal parts of the gland. The dorsal bud develops into the head and body of the organ. These two parts fuse at day 37 in utero. The drainage from the two parts seems separated by the axis of the superior mesenteric artery. The right part of the pancreas is drained by station 13 whereas the left part drains towards station 11.37 These two stations are next to last, draining into station 16 .

Fig. 2.5 Diagram of the lymph nodes draining the pancreas.

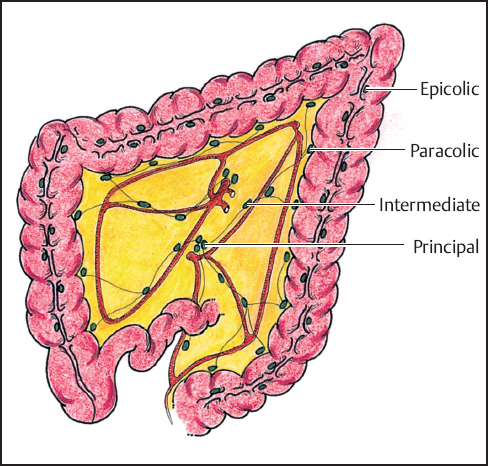

Fig. 2.6 Diagram of the lymph nodes draining the colon.

Colon and Rectum

There are several levels of nodal drainage. The colon has epicolic nodes along the taenias, then the paracolic nodes in the mesentery near the bowel. The drainage for the intestines is then towards the intermediate nodes which follow the blood vessels. The lymph then drains towards the central nodes. The small bowel and right colon then drain towards the superior mesenteric nodes whereas the left colon drains to the inferior mesenteric nodes. The last nodes are the pre- and paraaortic nodes (Fig. 2.6).36

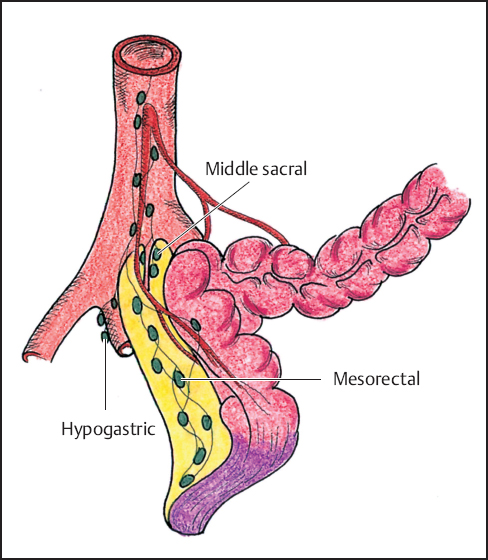

The lymph drainage of the rectum is to the nodes in the mesorectum then the paraaortic nodes.39 A second, deeper, set of nodes are the midsacral nodes, the internal iliac nodes, and the obturator nodes. These last two groups also drain the wall of the lesser pelvis (Fig. 2.7).40

Fig. 2.7 Diagram of the lymph nodes draining the rectum.

Lavage

There are two roles for lavage. These are technically challenging operations and a clean operative field is a prerequisite for successful surgery. Regular washing will maintain clear visualization of structures. The second, more controversial role is to lyse any spilled tumor cells.41 This can be accomplished by using sterile water, a 2% solution of hydrogen peroxide, or a solution of dilute Betadine.

Vascular Grafts

Vascular Grafts

Multiorgan resections can at times require the resection of segments of vital vascular structures if they are involved by the tumor, such as the celiac trunk by a tumor of the body of the pancreas, the portal vein by a tumor of the head of the pancreas, the hepatic artery by a bile duct tumor, or the superior mesenteric artery by a sarcoma of the mesentery. In appropriately selected patients resecting affected vessels will allow a complete resection to be performed. When complete resection is achieved the vascular invasion in itself does not have a prohibitively negative prognostic implication. However, if vascular resection is considered it is important to have access to appropriate replacement vessels. Autologous tissue should often be preferred to synthetic grafts both for graft permeability and for their inherently better resistance to infection. There are three preferred options. Whenever it is thought that a graft may be required it is important to guarantee access to the vessel when positioning and draping the patient.

Saphenous Vein

The saphenous vein is a very good substitute for medium-sized arteries such as the superior mesenteric or hepatic artery. We always ensure access to it when performing multivisceral resections.

Internal Jugular Vein

This is a very good substitute for the portal vein or the external iliac vein.

Internal Iliac Artery

This makes a very good substitute for bifurcating arteries or when the saphenous vein is not available. The internal iliac artery can be used to replace the bifurcation of the hepatic artery.

Teamwork or “Tour de Force” by the Maestro?

Teamwork or “Tour de Force” by the Maestro?

Presently, many surgeons will not have the expertise to carry out all these long, complex, and stressful procedures, especially if specialized vascular, orthopedic, urological, or thoracic expertise is required. It is essential to remain within one’s comfort zone of technical expertise and to recognize when help will or may be required so that appropriate colleagues will be available at the time of surgery. As in all fields of surgery expertise leads to shorter, smoother operations, and better outcomes. This is a field of surgery that does not tolerate the overambitious gladly at all.

As in all team endeavors it is important to have a designated leader. However, a cohesive team approach is necessary from the outset to ensure that the appropriate preoperative examinations are performed. Mutual respect will ensure technical excellence and a smooth operation. This starts with the positioning and draping of the patient in a way satisfactory to all. Likewise the incision(s) must be tailored to the needs of all.

Plenty of time should be set aside for these operations and if they will cover more than one shift adequate provisions need to be made by the nursing staff. It is virtually mandatory to have an ICU bed available for the immediate postoperative period. Careful consideration should be given to the use of transfusion sparing techniques. The use of cell-savers is considered inappropriate by some, controversial by others, and is acceptable to yet others. The blood bank should be warned if major vessels could be involved or if platelet transfusions are thought to possibly be necessary.

In the postoperative period the team must remain cohesive to obtain the best results and also to deal appropriately with possible complications. Each member must assume complete responsibility for his/her part of the operation, as for any other patient. This autonomy must be respected by all, especially the team leader. The patient should be officially referred to the surgeon who will be performing the bulk of the operation and follow-up. There is no scope for financial chicanery in this field of surgery. The old adage “proper planning and preparation prevent piss-poor performance” holds particularly true for this field of surgery.

Finally, it is essential that the anesthesiologist be actively involved in every aspect of the patient’s care. This needs to be a named individual who will assume personal responsibility for every aspect of the patient’s journey including the preoperative assessment, the intraoperative management and, ideally, the postoperative care.

The Patient

The Patient

These operations are a major undertaking, both for the surgeon and for the patient. They can have significant morbidity and influence on quality of life so careful consideration must be given to the perceived prognosis before proposing this type of resection to a patient. If there is a perception that the risks outweigh the benefits the patient should be referred to the oncologist for palliative therapy. Good patient selection is of paramount importance to maintain acceptable morbidity and mortality as well as good results.

These are not operations for frail patients or the faint-hearted. The patient’s active cooperation is essential in obtaining good results, as for all major surgery. The risks/benefits/uncertainties should be discussed very openly with the patient (and ideally with his/her family) and true informed consent is essential.

It is absolutely essential to have a complete preoperative work-up on these patients. Active coronary artery disease must be ruled out-there is scope for considerable blood loss and perioperative coronary events can have catastrophic consequences. If necessary, preoperative angiography and stent placement should be considered. This will mandate a 4-week delay in surgery so that the patient can receive adequate antiplatelet therapy while the endothelium covers the stent. Ideally the patient should be maintained on low-dose aspirin throughout the perioperative period to reduce the risk of stent occlusion. Similarly the patient needs to have adequate lung function. The patient’s general and/or respiratory condition may require 2-3 weeks of optimization prior to surgery. This can have a considerable beneficial influence on outcome. Similarly the patient’s nutritional status is of prime importance. If the patient has lost more than 10% of his/her body mass then surgery should be deferred for at least 2 weeks while the patient’s nutritional status is corrected. Small bore feeding tubes with continuous or intermittent tube feeds in addition to a healthy diet can be of considerable benefit. This optimization of nutritional status can be an on-going process along with other measures to improve the patient’s general condition, integrated with smoking cessation, bronchial toilet, and a graded exercise program. All necessary specialists should be called in (cardiology, respiratory medicine, nutritionists, and physiotherapists). The principle surgeon should keep a close eye on the patient-the logistics of these procedures can be quite complex and any change in plan will involve many people. Keeping them informed of progress focuses the team on these rather special patients. This also helps to motivate the patient.

Specific Principles

Specific Principles

Above the Mesocolon

Above the Mesocolon

This part of the abdomen is quite asymmetrical and the surgery is quite different on each side. The retroperitoneal structures, especially the pancreas, will play a key role. Multiorgan resections are highly dependant on the vascular anatomy and lymphatic drainage which have considerable influence both on the operation itself and its prognosis.

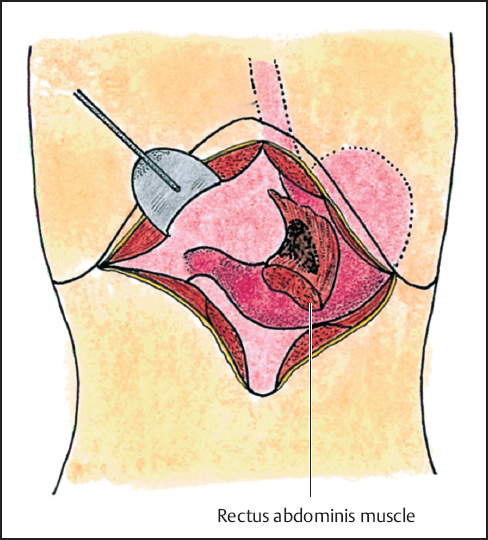

Fig. 2.8 Gastric cancer invading the left rectus muscle. A bilateral subcostal incision allows the approach to the aponeurosis of this muscle. The left rectus is then divided at a distance above and below the tumoral invasion and remains attached to the stomach.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree