Fig. 2.1

Anatomical structure of the mandibular gingiva

(3)

Buccal mucosa: According to the UICC classification, the mucosal layer of the cheeks, mucosa of the upper and lower alveolobuccal sulci (oral vestibule), mucosa in the retromolar areas, and labial mucosa of the upper and lower lips are collectively termed the buccal mucosa.

(a)

Mucosal layer of the cheeks: Area between the upper and lower buccal sulci.

(b)

Upper and lower alveolobuccal sulci (oral vestibule): Area extending from the distal surface of the canine anteriorly to the palatoglossal arch posteriorly. This square-shaped area is surrounded by the mucogingival junction and the junction on the buccal mucosa 1 cm from the deepest point in the buccal sulcus.

(c)

Retromolar areas: The area posterior to the gingiva, forming the margin of the tonsillar fossa.

(d)

Labial mucosa of the upper and lower lips: A square region bordered by the line connecting the corner of the mouth and the distal surface of the canine on the maxilla or mandible, the mucocutaneous junction, and the line 1 cm from the deepest part of the labial groove toward the mucocutaneous junction.

(4)

Floor of mouth: The mucosa of the FOM is bordered by the mucogingival junction on the lingual side of the mandible and the tongue–FOM junction.

(5)

Hard palate: The mucosa of the hard palate is the triangular region encompassed within the borderline between the horizontal and vertical regions of the palate, the midline of the palate, and the borderline with the soft palate which lacks bone.

2.2.2 Locations of the Lesions (Fig. 2.2)

Fig. 2.2

Anatomical sites and subsites

Tongue (TON-0, 1, 2)—dorsal surface (0)/lateral borders (1)/ventral surface (2)

Upper gingival and alveolus (UG)

Dentulous jaw (teeth: 8/7/6/5/4/3/2/1/1/2/3/4/5/6/7/8)

Edentulous jaw (Molar/Premolar/Canine/Incisor/I/C/P/M)

Lower gingiva and alveolus (LG)

Dentulous jaw (teeth: 8/7/6/5/4/3/2/1/1/2/3/4/5/6/7/8)

Edentulous jaw (Molar/Premolar/Canine/Incisor/I/C/P/M)

Buccal mucosa (BM-0, 1, 2, 3, 4)

Buccal mucosa (0)/upper buccoalveolar sulcus (oral vestibule) (1U)/lower buccoalveolar sulcus (oral vestibule) (1 L)/retromolar area(2)/upper labial mucosa (3)/lower labial mucosa (4)

Anterior type (a)/posterior type (b)

Floor of mouth (FOM)—median type (a)/lateral type (b)

Hard palate (HP)

(1)

According to the UICC classification, the tongue is divided into three subsites: the dorsum of the tongue anterior to the circumvallate papillae (anterior 2/3 of the tongue) (TON-0), the lateral boaders of the tongue (TON-1), and the inferior (or ventral) surface of the tongue (TON-2).

(2)

The location of lesions in the upper and lower gingival cancer is determined in relation to the teeth on the dentulous jaw or the corresponding teeth on the edentulous jaw. In the latter case, the location of lesion may be specified as an anterior teeth region (A), premolar region (P), or molar region (M). Because the presence and absence of teeth is thought to affect the progress of gingival cancer, the presence of impacted teeth should be recorded.

(3)

Similarly, the location of buccal mucosal cancers is determined by dividing the buccal mucosa into five subsites: the mucosa of the cheeks (BM-0), the upper and lower alveolobuccal sulcus (oral vestibule) (BM-1), the retromolar area (BM-2), the labial mucosa of the upper lip (BM-3), and the labial mucosa of the lower lip (BM-4). In addition, because the tissue structure deep inside the oral mucosa varies depending on the anatomical locations, buccal mucosal cancers are further classified into the anterior or posterior type. Anterior type (the mucosa of the cheeks, most of the oral vestibule, and the upper and lower labial mucosae): muscles and fat tissue are present beneath the mucosa, and the outermost layer is the skin. Posterior type (primarily retromolar area): due to the presence of the masseter muscle just adjacent to the buccinator muscle, the medial pterygoid muscle on the side of the pharynx, and the mandible, tumors readily extend into the space between the muscles of mastication (hereinafter masticator space), which is among the poor prognostic factors for oral cancer. Consequently, it is useful to subclassify buccal mucosal cancers into the anterior or posterior type with respect to the anterior margin of the masseter muscle.

(4)

FOM cancers are subclassified into the medial and lateral types. Medial FOM cancers are located in the anterior region of the FOM mesial to the junction of the canine and the first premolar on the mandible. Any cancers located in the posterior region of the FOM distal to the region defined above are considered the lateral type. Medial-type FOM cancers, which account for the majority of FOM cancers, often expand into the opening of the salivary gland, sublingual caruncle, and eventually into the contralateral side of the FOM. This type of FOM cancer may also extend to the Wharton tube, sublingual gland, genioglossus muscle, geniohyoid muscle, and the lower anterior tooth area. The submandibular lymph nodes are a frequent site of cervical lymph node metastasis, but metastasis to the submental lymph nodes is rare. Lateral-type FOM cancers often originate from the lateral margin or the root of the tongue, and the determination of tumor range is sometimes difficult in advanced cases. There are two routes for lateral FOM cancers to invade adjacent tissues. First, along the mandibular periosteum, they may invade the mylohyoid muscle and submandibular space from the sublingual gland. These cancers may also invade internally the genioglossus muscle, geniohyoid muscle, styloglossus, and then the hyoglossus and posteriorly the medial pterygoid muscle (masticator space). Cervical lymph node metastasis often involves the submandibular and upper jugular lymph nodes.

2.2.3 Size

(long diameter) × (short diameter) × (thickness) cm

(mesiodistal diameter) × (buccolingual diameter) × (thickness) cm

2.2.4 Clinical Types

Superficial type: tumors primarily showing superficial growth

Exophytic type: those primarily showing exophytic growth

Endophytic type: those primarily showing endophytic growth

Unclassified type: those not belonging to any of the above types

Oral cancers are classified into superficial (Fig. 2.3a), exophytic (Fig. 2.3b), and endophytic (Fig. 2.3c) types based on the clinical manifestations. In general, early (T1, T2) tongue cancers are diagnosed by visual inspection and palpation; however, it is preferable to perform ultrasonographic (US) imaging to confirm the diagnosis. Although visual inspection and palpation are performed to determine tumor invasion depth in or under the mucosal layer, because of individual variations in palpation skills among clinicians, diagnostic accuracy may have a margin of error of ±0.5 cm. Nonetheless, for the diagnosis of T1-2 cancers in soft tissue, palpation can provide fairly accurate supplementary findings to visual inspection. With continued advances in and dissemination of probe-based US examination, it may be possible in the near future to determine the invasion depth of tumors in millimeter increments. At that point, it will be necessary to reestablish a next-generation classification method for invasion patterns of tumors including those in gastric cancer.

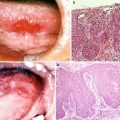

Fig. 2.3

Clinical types. (a) Superficial type. (b) Exophytic type. (c) Endophytic type

A previous study investigating the efficacy of clinical classification in 2,224 patients with T1-2 tongue cancer [5] revealed that this clinical type can be used as a prognostic factor for local recurrence, lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, and 5-year survival rate (Fig. 2.4a, b). Although such classification has some utility in buccal mucosa and FOM cancers, utility is affected by the site of the tumor. Consequently, we decided to subclassify buccal mucosa and FOM cancers into anterior/posterior type and medial/lateral type [6]. However, the utility of clinical classification based on growth patterns is not clear for cancers with a risk of bone invasion, such as gingival and hard palate cancers [7, 8], necessitating further investigation. As we describe later, the classification of lower gingival cancer by mandibular resorption type [9], which reflects mandibular invasion pattern [10], has proven useful [7, 10–13]. After incorporating diagnostic imaging that shows the pathological features at the apical end of cancer invasion, this classification method may be considered to fulfill all the requirements of a next-generation method. However, we decided to record the invasion of adjacent tissues in advanced oral cancers in detail without performing clinical classification, due to unproven utility.

Fig. 2.4

(a) Frequency of clinical types in lingual carcinoma. (b) Prognostic factors of clinical types

The clinical types of oral cancer, which are the superficial, exophytic, and endophytic types, correspond to the macroscopic classification of digestive tract cancers (e.g., esophageal, gastric, and colon cancers [14–16]), namely, type 0, type 1, and type 2–4, respectively. A small number of endophytic oral cancers are reported to be highly malignant, corresponding to type 4 oral cancer. Preliminary investigation of clinical cases at Saitama Cancer Center showed that 5 % of all T1-2 tongue cancers were the scirrhous type exhibiting the characteristic macroscopic features of a small ulcer with broad expansion into the deep tissue layer and with broad hard induration (Fig. 2.5a). In addition to these invasion patterns, such as broad invasion at depth and submucosal lateral infiltration (Fig. 2.5b Left, c), these cancers also exhibited histopathological features corresponding to a Yamamoto-Kohama’s (YK) Mode of Invasion [17] (Fig. 2.5b Right) of YK-4D and a scirrhous pattern, and they were also identified as a subtype with particularly poor prognosis, even among endophytic oral cancers (Fig. 2.5d). To improve the treatment of tongue cancer, further retrospective studies are being conducted to elucidate the pathological features associated with poor prognosis.

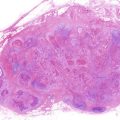

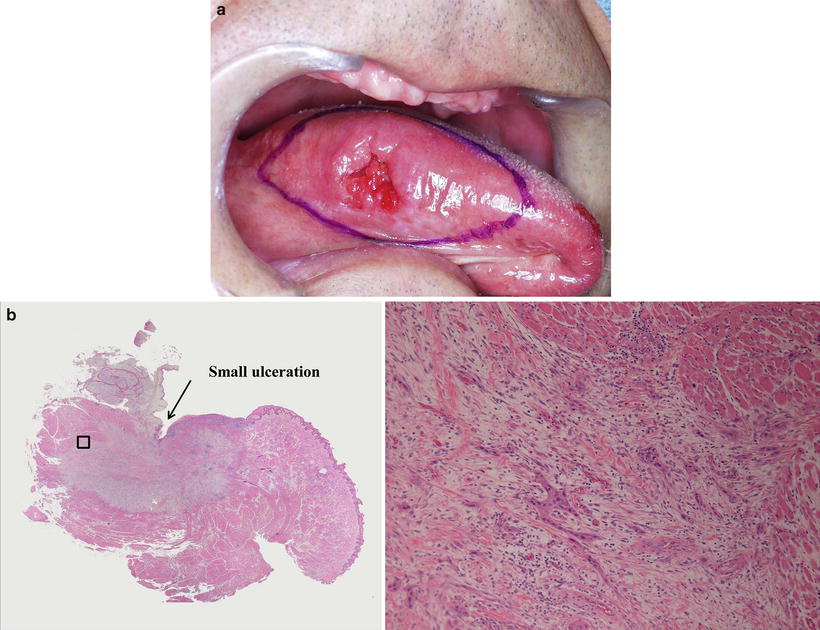

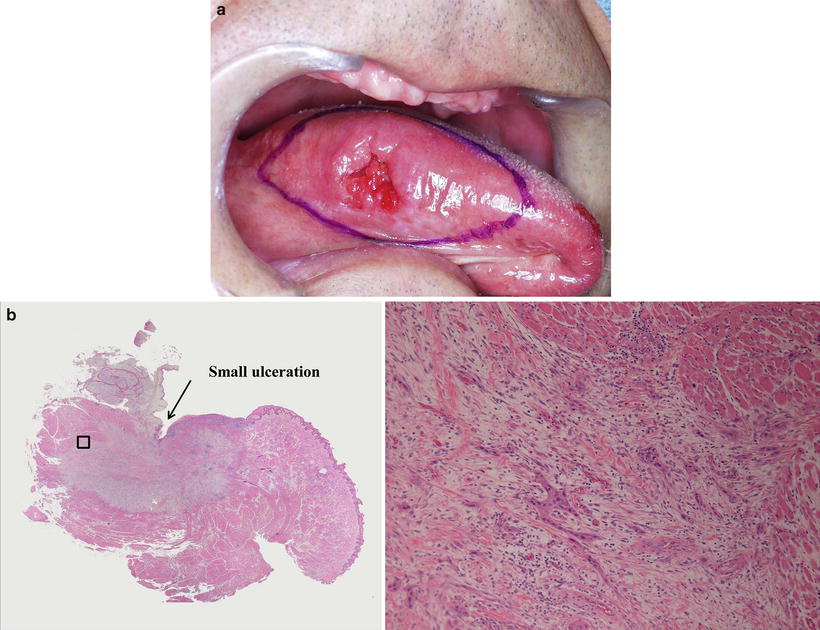

Fig. 2.5

(a) Macroscopic presentation of the scirrhous type of lingual carcinoma. Palpation of a small ulcer with broad expansion into the deep tissue layer and extensive induration (outlined in ink). (b) Histologic presentation of the scirrhous type of lingual carcinoma. Left panel: low-magnification image showing a small ulcer on the surface with broad expansion into the deep tissue layer. Right panel: high-magnification image of the opening showing diffuse invasion (YK-4D) of small nests or single cells. (c) Spread pattern of endophytic and scirrhous types of lingual carcinoma. Left panel: broad endophytic ulcer with tapering depth. Right panel: small ulcer with broad expansion in the deep tissue layer and lateral expansion in the submucosal layer. (d) Prognostic factors of the endophytic and scirrhous types of lingual carcinoma

2.2.5 Depth and Deepness of Invasion

Depth: Tissue name of the deepest part of cancer invasion. (See tissue names below according to subsite. Underlined tissue names refer to adjacent tissues.)

Deepness: Distance from the surface of the assumed normal mucosa to the deepest part of cancer invasion, which is different from the thickness of tumor.

T factors in the UICC classification of oral cancers are determined based on greatest tumor diameter. However, the prognosis of primary tumors correlates with tumor invasion depth much more strongly than with tumor diameter. For this reason, we plan to define the invasion depth of a tumor as the T factor in future studies. Determination of invasion depth is relatively easy in esophageal and gastric cancers because of the six clear layers of the wall: the mucosa (M), muscularis mucosae (MM), submucosa (SM), muscularis propria (MP), subserosa (SS), and serosa (S).

However, in oral cancers, it is not possible to standardize tumor depth because of the complex three-dimensional structure of the oral cavity, which has different deep tissue structures at different anatomical locations. Accordingly, albeit somewhat cumbersome, invasion depth of the vertical structures is recorded in detail from the mucosa to the deeper layers by anatomical site and subsite.

In the present rules, original evaluation criteria were developed for the invasion of adjacent tissues (T4a) by considering evaluation of the depth.

(1)

Invasion depth of tongue cancer

Tongue (TON): mucosa (M)/submucosa (SM)/shallow part of the proper muscle layer of the tongue (MP1)/deep part of the proper muscle layer of the tongue (MP2)/extrinsic muscles of the tongue (HG)

Scanning of a healthy tongue with the most widely used US [18–20] device shows three layers of different US intensities and features at the lateral boarder of the tongue, which is the most frequent site of the cancer. These are the outermost, second, and innermost layers of heterogenous hyperechoic or hypoechoic signal intensity (Fig. 2.6a). The outermost hyperechoic layer is thought to represent signal reflection at the mucosal surface, the second hypoechoic layer likely represents mucosa (M), and the innermost layer therefore represents submucosa (SM) and muscularis propria (MP). Because of the hyperechoic signal in the muscularis propria, cancer invading this layer is displayed as an area of hypoechoic intensity (Fig. 2.6b).

Fig. 2.6

(a) Ultrasonographic findings of normal lingual tissue. (b) Assessment of tumor invasion in the muscular layer and comparison between ultrasonographic and histological images. (c) Assessment of tumor depth

Given the extroverted growth of the tumor and the formation of a depression due to ulcer, it is important to measure the deepness of tumor from the assumed normal mucosal surface, instead of measuring the actual thickness of tumor (Fig. 2.6c). It is also important to record the method of measurement (palpation or US), the extent of tumor invasion in the existing structure, and the depth of invasion in centimeters if palpated or millimeters if scanned by US.

(2)

Invasion depth of upper gingival cancer

Upper gingival and alveolus (UG): mucosa (M)/submucosa (SM)/periosteum (PER)/ cortical bone (CB)/bone marrow (CAN)/maxillary sinus (MS) and nasal cavity (NC)

(3)

Invasion depth of lower gingival cancer

Lower gingiva and alveolus (LG): mucosa (M)/submucosa (SM)/periosteum (PER)/cortical bone (CB)/upper part of the mandibular canal in bone marrow (CAN1)/lower part of the mandibular canal in bone marrow (CAN2)

According to the UICC classification, superficial erosion alone of the bone/tooth socket by gingival primary carcinoma is not sufficient to classify a tumor as T4a, and consequently, the diagnosis of any mandibular infiltration beyond this point is crucial. By classifying mandibular infiltration patterns as shown in Fig. 2.7, the JSOT demonstrated the appropriateness of mandibular canal classification that defines CAN2 as T4a in a multicenter study of 1,187 cases of mandibular gingival cancer [23]. The present general rules define CAN2 in mandibular bone invasion as T4a.

Fig. 2.7

Invasion depth of lower gingival carcinoma

The mandibular invasion of lower gingival cancer is an important indication for surgery. The invasion depth of squamous cell carcinoma (SSC) in the mandible shows a fair correlation with the degree of mandibular resorption on X-ray absorptiometry [9, 12]. By also assessing the pattern of bone resorption, it is possible to determine which resection method is appropriate for the mandible [9, 11–13, 23]. Consequently, in addition to the invasion depth from the gingival mucosa, the images of mandibular resorption by lower gingival cancer should be examined carefully for the following points.

Note: Images of mandibular resorption

In the evaluation of the depth of lower gingival cancer, additional comments concerning the following findings on X-ray studies are attached.

(a)

Type of images examined

(b)

Degree of mandibular resorption: none/alveolar process of bone marrow/upper mandibular canal of bone marrow/lower mandibular canal of bone marrow

(c)

Deepest part of mandibular bone resorption:

Dentulous jaw (Retromolar/8/7/6/5/4/3/2/1/2/3/4/5/6/7/8/R)

Edentulous jaw (Retromolar/ Molar/Premolar/Canine/Incisor/I/C/P/M/R)

(d)

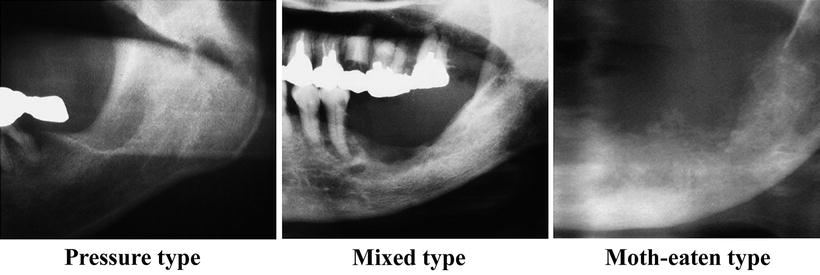

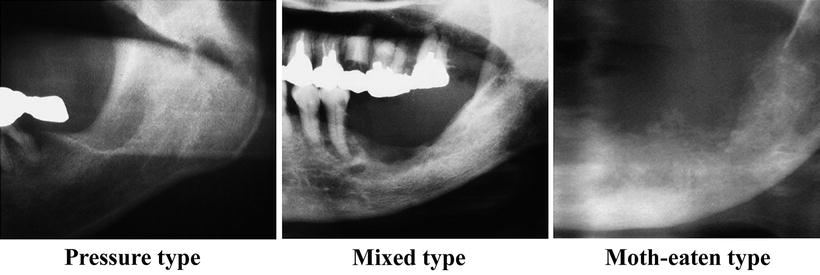

Mandibular resorption type: pressure type/mixed type/moth-eaten type

The patterns of bone resorption on radiograms are grouped into the pressure type, moth-eaten type, and mixed type in accordance with the Swearingen classification [9] (Fig. 2.8). It is common to observe all bone resorption patterns distributed continuously on the same radiogram of upper or lower gingival cancer.

Fig. 2.8

Patterns of bone resorption in lower gingival carcinoma

(1)

Pressure type: The margins of bone resorption are clear and smooth with no displaced bone fragments.

(2)

Mixed type: Despite somewhat unclear and irregular margins of bone resorption, no displaced bone fragments are observed.

(3)

Moth-eaten type: The margins are unclear and irregular, and bone fragments are observed.

(4)

Invasion depth of buccal mucosal cancer

Buccal mucosa (BM): mucosa (M)/submucosa (SM)/buccinator muscle (oral orbicular muscle) (BM, OOM)/buccal sulcus (BS)/buccal fat (BF)/muscles of facial expression and superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) (FM)/subcutaneous fat (SCF)

Anterior type: buccal space→muscles of facial expression and superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) (FM)/subcutaneous fat (SCF)

Posterior type: buccal space→masticator muscle space (MS)

Because of the small number of cases and the complex deep tissue structure, a search of the literature does not produce sufficient information on the clinical and pathological features of buccal mucosal cancer. In the general rules, buccal mucosal cancers are subclassified into the anterior and posterior type on the basis of deep tissue structure. It is important to carefully examine diagnostic images and histopathological samples to accumulate sufficient information on tumor depth in the mucosa, submucosal tissues, buccinator muscle, buccal space, buccal fat pad, muscles of facial expression interlinked via the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) [27, 28], subcutaneous fat, skin, masticator space, maxilla, and mandible, as well as information on the invasion of the surrounding tissues.

(5)

Invasion depth of FOM cancer

Floor of mouth (FOM): mucosa (M)/submucosa (SM)/sublingual space (SLS)/mylohyoid muscle (MH)/submandibular space (SMS)

Median type: sublingual space→genioglossus muscle (GG)/geniohyoid muscle (GH)/ mylohyoid muscle (MH)/submandibular space (SMS)

Lateral type: sublingual space→mylohyoid muscle (MH)/submandibular space (SMS)

Median-type FOM cancers infiltrate into the tissues surrounding the Wharton duct immediately below the mucosa and sublingual gland in the relatively early stages; these cancers infiltrate into the genioglossus (extrinsic tongue muscle) and may further advance into the geniohyoideus and mylohyoideus muscles and the submental space. Lateral-type FOM cancers infiltrate into the mylohyoid and submandibular space vertically via the tissues surrounding the Wharton duct and sublingual gland. In addition, it is important to pay clinical attention to the invasion of the intrinsic muscles of the tongue, the outer periosteum on the mandibular lingual side, and the masticator space.

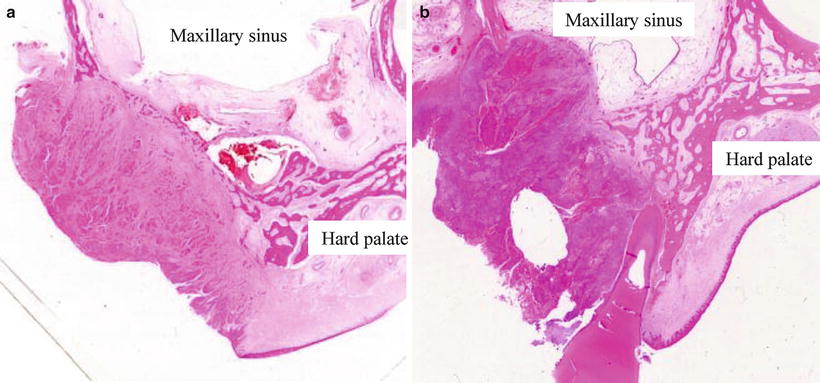

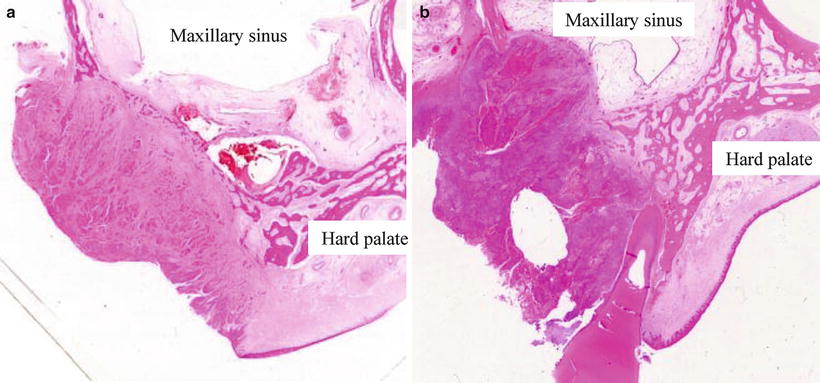

(6)

Invasion depth of hard palate cancer

Hard palate (HP): mucosa (M)/submucosa (SM)/periosteum (PER)/cortical bone (CB)/bone marrow (CAN)/maxillary sinus (MS) and nasal cavity (NC)

In general, hard palate cancers located in the posterior region have poor prognosis and a high risk of lymph node metastasis. Prognosis for hard palate cancers invading the nasal cavity and maxillary sinus is thought to be even worse; however, hard palate cancers have not been studied in great detail due to the extremely small number of cases. To reveal their clinical manifestations, it is necessary to carefully investigate their invasion depth into surrounding tissues, including the nasal cavity and maxillary sinus. At present, we tentatively use the SNF criteria [21, 22], which classify tumor invasion in the maxillary sinus and nasal cavity as T4a.

2.2.6 Invasion into Adjacent Structures

In principle, the UICC TNM classification of malignant tumors [3] is used to assess the infiltration of primary lesions, except T4a lesions, into surrounding tissues. For T4a lesions, we propose our own classification criteria specific to the site of invasion, as described below. In the following section, we review the association between T factors and the UICC classification.

(1)

Invasion into adjacent tissues by tongue cancer

None/FOM/sublingual space/mylohyoid muscle/extrinsic muscles of the tongue/root of the tongue/gingiva/mandibular cortex/mandibular bone marrow

The tongue consists of four extrinsic muscles (genioglossus, hyoglossus, styloglossus, and palatoglossus) and four intrinsic muscles (superior longitudinal, inferior longitudinal, verticalis, and transversus muscles). Infiltration into the intrinsic muscles is used as an indication of deep tissue invasion in T4a tumors. Infiltration into individual intrinsic muscles is not regarded as an indication of T4a tumors. The intrinsic muscles move the tongue, whereas the extrinsic muscles change its shape during swallowing and speech. For example, the genioglossus muscle moves the tongue anteriorly or toward the mentum, whereas the hyoglossus pulls the root of the tongue posteriorly. In addition, the styloglossus pulls the tongue toward the upper posterior direction, and the palatoglossus plays a role in narrowing the faucial area by elevating the root of tongue and lowering the palate. The lingual and hypoglossal nerves serve to regulate the tongue’s sensory and motor functions, respectively. The extent of invasion is diagnosed while taking account of the function of individual muscles and nerves as well as the current symptoms. With regard to bone metastasis, infiltration into bone marrow is clearly an indication of T4a. In addition, as in the other oral cancers, the diagnosis of T4a is made when the submandibular space is infiltrated via the mylohyoid muscle. Invasion into the skin, which also appears in the UICC classification criteria, occurs only through the mandible or submandibular space and therefore is excluded from the criteria for T4a lesions in these general rules. T4b is also diagnosed upon tumor invasion into the posteriorly located masticator space. The UICC T4b criteria are used for infiltration into the internal carotid artery and pterygoid process, both of which rarely occur without the invasion of the masticator space.

(2)

Invasion of adjacent tissues by upper gingival cancer

None/maxillary sinus/nasal cavity/buccinator muscles/buccal space/muscles of facial expression/masticator space/pterygoid plate/skull base/internal carotid artery/subcutaneous fat/skin

Figure 2.9 shows the potential infiltration routes of upper gingival and hard palate cancers into the surrounding tissues in the coronal section. In these general rules, infiltration into surrounding tissues beyond the buccinator muscle is classed as T4a in upper and in lower gingival cancer. Because the orbicularis oris muscle and buccinator muscles are adjacent to each other, any tumor invasion beyond the orbicularis oris muscle is diagnosed as T4a as well. In contrast to the UICC classification for lower gingival cancer, which defines T4a by bone marrow infiltration, we define tumor invasion reaching the mandibular canal as T4a. However, compared with the mandible, the bone cortex of the maxilla is thin and thus readily allows tumor invasion into the bone marrow. Accordingly, the invasion of the nasal cavity or maxillary sinus, but not the bone marrow, is also defined as T4a for upper gingival cancers in accordance with the SNF criteria (Fig. 2.10). Infiltration into the skin, which is described in the UICC classification, occurs only through the buccinator muscle and therefore is excluded from the T4a criteria in these general rules. As described earlier, anterior and posterior infiltration into the buccal space and subcutaneous fat is considered to be T4a. However, as described in the section on buccal mucosal cancer, none of the infiltration routes in the horizontal direction (Fig. 2.11) are considered T4b (the routes in Figs. 2.9a and 2.11a). The most important factor that affects prognosis is tumor invasion in a posterior direction. Because infiltration into the medial and lateral pterygoid muscles, masseter muscle, and temporal muscle is invasion of the muscles of mastication (the routes in Fig. 2.11c–e) and because of the potential invasion of the pterygoid process (the route in Fig. 2.11b), infiltration into these muscles is defined as T4b in accordance with the UICC classification.

Fig. 2.9

Invasion routes of upper gingival and hard palate carcinomas on a coronal section

Fig. 2.10

Maxillary invasion of upper gingival carcinoma according to the sinus and nasal floor criteria. (a) The carcinoma advancing through and expansively absorbing the bone marrow on the buccal side is not classified as T4a because of no infiltration into the maxillary sinus. (b) The carcinoma infiltrating the maxillary sinus through the bone is classified as T4a

Fig. 2.11

Invasion routes of upper gingival carcinoma in the horizontal section

(3)

Invasion of adjacent tissues by lower gingival cancer

None/FOM/sublingual space/tongue/buccal mucosa/buccinator muscles/buccal space/ masticator space/muscles of facial expression/subcutaneous fat/skin

The progression of lower gingival cancer toward the buccal mucosa may lead to tumor infiltration into the buccinator muscle, buccal space, and even the skin (Fig. 2.12a). In the direction of the FOM, lower gingival cancer may infiltrate superficially into the lingual gingiva, FOM mucosa, and even the tongue (Fig. 2.12b) and infiltrate deeply into the sublingual gland, Wharton duct, lingual nerve, and as far as the submandibular space via the mylohyoid muscle (Fig. 2.12c). The progression of lower gingival cancer toward the retromolar areas may cause invasion of the submandibular space via the posterior edge of the mylohyoid muscle medially (Fig. 2.12d), invasion of the masseter muscle via the buccinator muscle laterally (Fig. 2.12e), and invasion of the base of the skull and the parapharyngeal space via the pterygomandibular space posteriorly (Fig. 2.12f). In the JSOT general rules, tumor infiltration reaching the mandibular canal via the deep interior region of the mandible is defined as T4a. Invasion of the adjacent tissues that are defined as T4a includes the extrinsic muscles of the tongue on the FOM side, the submandibular space, and the skin, buccal space, and even subcutaneous fat on the buccal mucosal side. The problem associated with the UICC criteria of T4b for lower gingival cancers is the invasion of the masticator space because lower gingival cancers originating from the retromolar areas readily invade the masticator space (Fig. 2.13).

Fig. 2.12

Invasion routes of lower gingival carcinoma

Fig. 2.13

Masticatory space and pterygomandibular space

(4)

Invasion of adjacent tissues by buccal mucosal cancer

None/masticator space/lower gingiva/mandibular cortex/mandibular bone marrow/FOM/upper gingiva/maxillary cortex/maxillary bone marrow/ oropharynx/lips/subcutaneous fat/skin

The major invasion routes of FOM cancers into the adjacent tissues and the relationship between the routes and fascial spaces are shown in Fig. 2.14. In the upper and lower gingival cancer section of the JSOP general rules, the invasion of buccal space or subcutaneous fat is defined as T4a. However, it can be problematic to apply this definition as is because buccal mucosal cancers easily invade the buccal space. Figure 2.15 therefore shows the different degrees of invasion of buccal mucosal cancers in the coronal plane. The buccal space is present between the buccinator muscle and the SMAS muscles for facial expression and contains the buccal fat pad with a distinctive coating. Although invasion into the skin is defined as T4a in the UICC classification, the JSOT general rules define invasion of the subcutaneous fat via the buccal space or via the orbicularis oris muscle which lacks the buccal space as T4a. On the other hand, the invasion of the maxilla and mandible (Fig. 2.15f1, f2) is defined as T4a only when accompanied by bone marrow invasion, in accordance with the UICC classification. The posterior type of buccal mucosal cancer may bypass the buccal space and posteriorly invade the masseter muscle, i.e., the masticator space (the route in Fig. 2.14b). In this case, the invasion is defined as T4b in accordance with the UICC classification.

Fig. 2.14

Invasion routes of buccal mucosal and floor of mouth (FOM) carcinoma and fascial spaces

Fig. 2.15

Depth of buccal carcinoma on a coronal section

(5)

Invasion of adjacent tissues by FOM cancer

None/mylohyoid muscle/tongue/extrinsic muscles of the tongue /gingiva/mandibular cortex/mandibular bone marrow/submandibular space/masticator space/oropharynx

The invasion routes of FOM cancers in the coronal plane may involve the sublingual gland (a), intrinsic tongue muscles (b), extrinsic tongue muscles (c), mylohyoid muscle (d), and mandible (e), as shown in Fig. 2.16. Non-superficial lesions generally involve tumor invasion into the sublingual gland and rarely infiltration into the mandible or the submandibular space beyond the mylohyoid muscle. However, with regard to the progression of lateral FOM cancers in the posterior direction, attention must be paid to the invasion of the submandibular space via the posterior margin of the mylohyoid muscle and the invasion of the medial pterygoid muscle. The T4a definitions of FOM cancers conform to the corresponding UICC criteria, and accordingly, FOM cancers are defined as T4a when accompanied by the invasion of the extrinsic tongue muscles and mandibular bone marrow and the invasion of the submandibular space by coming around the posterior margin of the mylohyoid muscle (the route in Fig. 2.14d) or by passing over the mylohyoid muscle (the route in Fig. 2.14c). Invasion into the skin is excluded from the UICC T4a criteria because it is possible only via the mandible or submandibular space. Invasion of the medial pterygoid muscle is defined as T4b in accordance with the UICC classification because the invasion is equivalent to the invasion of the masticator space (the route in Fig. 2.14f).

Fig. 2.16

Invasion routes of FOM carcinoma on a coronal section

(6)

Invasion of adjacent tissues by hard palate cancer

None/maxillary sinus/nasal cavity/gingiva/soft palate/masticator space/ pterygoid plate/skull base/internal carotid artery

The potential invasion routes of upper gingival and hard palate cancers in the coronal plane are shown in Fig. 2.9. Although hard palate cancers may invade posteriorly into the soft palate, pterygoid process, and medial pterygoid muscle (masticator space), invasion of the soft palate is not included in the UICC T4 criteria. On the other hand, despite the contiguous mucosal structure, invasion of soft palate cancer (oropharyngeal cancer) into the hard palate is considered to be T4a according to the UICC criteria. To ensure consistency among the criteria, it may be necessary to define the invasion of hard palate cancer into the soft palate as T4a. However, define such simple invasion of contiguous anatomical regions as T4a independently of the depth is questionable. We will therefore continue to investigate the prognosis of soft palate cancer accompanied by invasion of the hard palate.

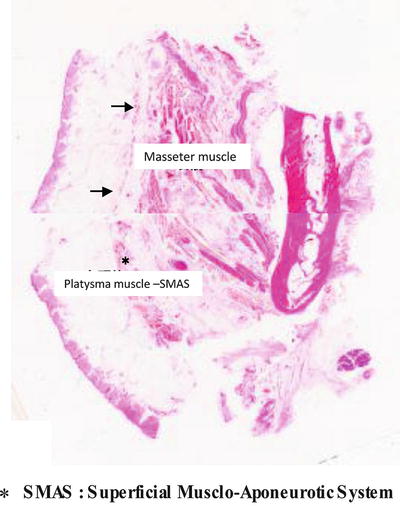

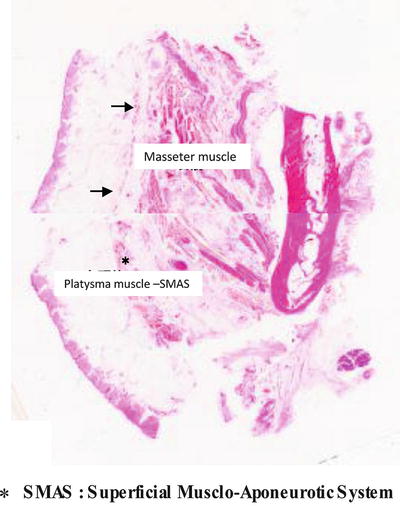

Note: Description of the superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS)

In 1976, Mitz et al. reported the presence of the SMAS [27], which is connected to the platysma muscle, muscles of facial expression, temporoparietal fascia, and galea aponeurotica [28]. The SMAS is an important anatomical structure in cosmetic surgery, especially rhytidectomy, because the system stabilizes facial expression and transmits contraction signals to the facial skin. Compared with the adipose tissue medial to the SMAS, the adipose tissue lateral to it (i.e., toward the skin) contains small adipocytes partitioned by fibrous tissues that transmit muscular movement to the skin. The SMAS is wide at the para-parotid gland area but becomes thinner and discontinuous anteriorly. As indicated by the arrow in the coronal section of the masseter muscle stained with hematoxylin and eosin of Fig. 2.17, the SMAS is contiguous to the platysma muscle and forms a thin layer of muscle or a layer of connective tissue outside the masseter muscle.

Fig. 2.17

Histologic figure at the masseter muscle on a coronal section

2.2.7 T Score

The assessment of T score in primary tumors, except T4a tumors, is performed in accordance with the UICC TNM malignant tumor criteria [3].

TX: Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0: No evidence of primary tumor

Tis: Carcinoma in situ (squamous intraepithelial neoplasia)

T1: Maximum diameter ≤2 cm

T2: Maximum diameter >2 and ≤4 cm

T3: Maximum diameter >4 cm

T4: Invasion into adjacent structures

However, as stated earlier, the criteria for T4a lesions were developed by invasion sites, and therefore we summarize the differences between our general rules and the UICC classification below.

In addition, tumors 2–3 and 3–4 cm in the greatest diameter are occasionally called early T2 and late (or advanced) T2, respectively. This appears to be an effective subclassification for:

<Comparative relations to the UICC T4a criteria>

(1)

Tongue cancer:

T4a: Invasion into the mandibular bone marrow, invasion into the submandibular space, and invasion into the extrinsic tongue muscles

T4b: Invasion into the masticator space, invasion into the pterygoid plate, invasion into the skull base, and invasion circumferentially surrounding the internal carotid artery

Addition of “invasion into the submandibular space”

Omission of “invasion into the skin” in the UICC classification because it does not occur without the invasion of the mandible or submandibular space

Deletion of “invasion into the maxillary sinus” in the UICC classification

Retention of “invasion into the mandibular bone marrow” and “invasion into the extrinsic tongue muscles” in the UICC classification

(2)

Upper gingival cancer:

T4a: Invasion into the maxillary sinus and nasal cavity and invasion into the buccal space or subcutaneous fat

T4b: Invasion into the masticator space, invasion into the pterygoid plate, invasion into the skull base, and invasion circumferentially surrounding the internal carotid artery

Note 1: If the tumor is confined to the alveolar bone, the tumor is classified as T1-3 according to its size.

Note 2: Tumors invading the maxillary sinus are judged to be T4a regardless of their size.

Omission of “invasion of the bone marrow” and change of “invasion of the maxillary sinus” in the UICC classification to “invasion of the maxillary sinus and nasal cavity”

Change of “invasion of the skin” in the UICC classification to “invasion of the buccal space or subcutaneous fat”

Omission of “invasion of the extrinsic tongue muscles” in the UICC classification

(3)

Lower gingival cancer:

T4a: Invasion reaching the mandibular canal, invasion into the buccal space or subcutaneous fat, invasion into the submandibular space, and invasion into the extrinsic tongue muscles

T4b: Invasion into the masticator space, invasion into the pterygoid plate, invasion into the skull base, and invasion circumferentially surrounding the internal carotid artery

Note 1: If the tumor is confined to the upper part of the mandibular canal in the bone marrow, the tumor is classified as T1-3 according to its size.

Note 2: Tumors invading the mandibular canal are judged to be T4a regardless of their size.

Addition of “invasion of the submandibular space”

Change of “invasion of the skin” in the UICC classification to “invasion of the buccal space or subcutaneous fat”

Change of “invasion of the bone marrow” in the UICC classification to “invasion reaching the mandibular canal”

Omission of “invasion of the maxillary sinus” in the UICC classification

Retention of “invasion of the extrinsic tongue muscles” in the UICC classification”

(4)

Buccal mucosal cancer:

T4a: Invasion into the subcutaneous fat, invasion into the maxillary and mandibular bone marrow, and invasion into the maxillary sinus

T4b: Invasion into the masticator space, invasion into the pterygoid plate, invasion into the skull base, and invasion circumferentially surrounding the internal carotid artery

Change of “invasion of the skin” in the UICC classification to “invasion of the subcutaneous fat”

Retention of “invasion of the mandibular bone marrow” and “invasion of the maxillary sinus” in the UICC classification

Omission of “invasion of the extrinsic tongue muscles” in the UICC classification

(5)

FOM cancer:

T4a: Invasion into the mandibular bone marrow, invasion into the submandibular space, and invasion into the extrinsic tongue muscles

T4b: Invasion into the masticator space, invasion into the pterygoid plate, invasion into the skull base, and invasion circumferentially surrounding the internal carotid artery

Addition of “invasion of the submandibular space”

Omission of “invasion of the skin” in the UICC classification because it does not occur without the invasion of the mandible or submandibular space

Omission of “invasion of the maxillary sinus” in the UICC classification

Retention of “invasion of the mandibular bone marrow” and “invasion of the extrinsic muscles of the tongue” in the UICC classification

(6)

Hard palate cancer:

T4a: Invasion into the maxillary sinus and nasal cavity

T4b: Invasion into the masticatory muscle space, invasion into the pterygoid process, invasion into the base of the skull, and invasion circumferentially surrounding the internal carotid artery

Addition of “nasal cavity” into “invasion of the maxillary sinus” in the UICC classification while omitting “invasion of the mandibular bone marrow”

Change of “invasion of the skin” in the UICC classification to “invasion of the buccal space or subcutaneous fat”

Omission of “invasion of the extrinsic tongue muscles” in the UICC classification

2.2.8 Histological Classification

2.2.8.1 Tis Cancer: Oral Intraepithelial Neoplasia (OIN)/Carcinoma In Situ

(1)

Basaloid type

(2)

Differentiated type

The histological classification of early oral SCC has been performed universally in accordance with WHO’s classification of “dysplasia” [29–31], which grades the severity of dysplasia as mild, moderate, or severe and defines carcinoma in situ (CIS) as a precursor to oral SCC. The definition of CIS as the presence of atypical cells in all layers of the epithelium has remained unchanged since the first edition (1971). However, this diagnostic criterion is controversial because the criterion was established by emulating the pathological concept of dysplasia in cervical cancer [32–34] and because differentiated precancerous lesions and CIS are typically present in the mucosa of the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx [35–41]. Against this background, when the classification of squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (SIN) [39–42] and the Ljubljana classification of laryngeal lesions [43–54] were proposed, WHO included these classifications alongside the criteria for dysplasia in head and neck tumors (2005) [31]. Nevertheless, in the WHO classification, the pathologic concept of dysplasia and SIN includes both neoplastic lesion and atypical reactive lesion. This concept is not only incomplete for pathological classification but also useless as a diagnostic indicator for deciding the treatment strategy. Furthermore, it remains a descriptive diagnosis and cannot be used to qualitatively diagnose tumor malignancy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree