Surgical Management of Penile Cancer

Paul Russo

Simon Horenblas

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 95% of penile cancers are squamous cell cancers (SCCs), a disease associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Penile cancers are rare in the United States and European countries (0.4%-0.6% of all malignancies) but common in tropical and subtropical regions of Latin America, South America, Asia, India, and Africa (10%-20% of all malignancies). The overall annual experience in the United States and Europe, even in tertiary referral centers, is limited. Risk factors associated with penile cancer include lack of circumcision, phimosis, chronic inflammation, numerous sexual partners, and cigarette smoking. Human papilloma virus (HPV), particularly the oncogenic strain HPV 16 has been detected in between 30% and 100% of penile cancer specimens (1). Hernandez et al. used the United States SEER database to analyze 4,967 patients from 1998 to 2003 which represented <1% of new cancers in men during that time frame. Rates of penile cancer in Hispanics were 72% higher than non-Hispanics, and rates were higher in southern states and regions of lower socioeconomic status. The authors speculate that HPV vaccination may potentially decrease the incidence of this disease in the future (2). Recent reports on incidence figures have shown a decrease in the United States; however, no change was seen in the Netherlands (3).

Effective surgical intervention, fundamental throughout the natural history of this malignancy, plays an essential role in both the diagnosis and management of the primary penile cancer (4). In addition, operative intervention is essential for accurate staging and therapy for regional inguinal and pelvic lymph nodes. The main principle of surgical treatment of the primary tumor is to resect the penile cancer with adequate margins and attempt to leave as much functional penis as possible for upright voiding and sexual function (5,6). Delayed or incomplete surgical interventions can have an adverse effect on patient survival, a situation made worse by the absence of effective systemic chemotherapy. Moreover, progression is often characterized by loco regional progression only with ulcerating, foul smelling inguinal metastases and lymphangitis that is very difficult to palliate. Regional inguinal and pelvic lymph node dissection (LND) remains an integral component of the treatment of invasive penile cancer with evidence mounting that a survival advantage exists for patients undergoing early as opposed to therapeutic groin dissection. Dynamic lymphoscintigraphy to identify the sentinel lymph node (SLN), a technique found highly effective in the management of melanoma and breast cancer, has increasingly been integrated into the care of patients with invasive penile cancer, particularly those presenting without adenopathy. For patients with bulky metastatic groin disease, strategies employing neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy are being utilized in order to convert unresectable disease into resectable disease, often with the use of myocutaneous and advancement flap coverage, to provide local tumor control and effective disease palliation.

PENILE CANCER: DISEASE, NATURAL HISTORY, AND PATTERNS OF RECURRENCE

An understanding of the pathology, natural history, and common recurrence patterns is essential for urological surgeons caring for penile cancer patients. Guimaraes and colleagues reported a clinicalopathological study of 333 patients with penile cancer from Brazil. Four patients underwent primary excision, 194 patients underwent partial penectomy, and in 133 patients, a total penectomy was performed. SCC was the histological subtype in 65% of the cases with mixed verrucous and condylomatous carcinomas, the most common variants and combined histological patterns. The predominant age peaks were the sixth and seventh decades of life with two thirds of the cases involving the glans or foreskin. Basaloid, sarcomatoid, and adenosquamous variants, usually of high grade, tended to involve the glans, whereas unusual tumors arising in the foreskin or coronal sulcus tend to be of the lower grade verrucous or papillary types. High T stage was associated with sarcomatoid and basaloid carcinomas, whereas verrucous carcinoma showed the lowest stage. Groin metastases occurred in 50% to 75% of sarcomatoid, basaloid, and adenosquamous carcinoma cases, were absent in verrucous carcinoma, and infrequent in mixed, warty, and papillary carcinoma cases. Tumor recurred in 75 patients (22%) including local recurrence in 6, regional recurrence in 41, and systemic recurrence in 11. Simultaneous local, regional or regional-systemic recurrence occurred in ten and seven cases, respectively. Only verrucous carcinoma was unassociated with regional recurrence. Overall survival in this cohort was 82% at 10 years with verrucous, adenosquamous, mixed, papillary, and warty carcinoma ranging from 90% to 100% survival as opposed to SCC and basaloid which had 78% 10-year survival (7).

In a study of 700 penile cancer patients from the Netherlands and Sweden managed from 1956 to 2007, 205 patients (29.3%) experienced a recurrence, 74.1% within 2 years and 92% within 5 years of diagnosis. Local recurrence occurred in 18.6%, regional recurrence in 9.3%, and metastatic recurrence in 1.4%. In this cohort, patients undergoing penile preserving operations (as opposed to partial penectomy), those initially staged as regional node positive, and those who were initially managed with active surveillance of the regional nodes were at highest risk for systemic progression and death from disease (8). Involvement of pelvic lymph nodes with metastatic SCC is a harbinger of fatal disease in most cases with ultimate disease dissemination occurring to bone, retroperitoneal nodes, liver, lungs, and brain leading to death. Despite systemic chemotherapy, once systemic disease occurs survival is usually measured in months (9).

DIAGNOSIS OF THE PRIMARY PENILE LESION

When a suspicious penile tumor or ulcer is encountered, a decision concerning the extent of the biopsy procedure is made depending on the location of the lesion. Any penile lesion that is not healing after a period of 2 to 3 weeks of careful observation, meticulous hygiene, and skin care should be biopsied. For small discrete lesions, the biopsy procedure can be at the same time diagnostic and therapeutic. The biopsy specimen, regardless of location, must contain adequate underlying tissue to allow the pathologist to determine the depth of tumor invasion, an important predictor of local tumor recurrence and regional nodal metastases (10,11). Patients with noninvasive cancers (i.e., carcinoma in situ [CIS]) that are completely excised with negative margins must be carefully monitored with frequent physical examinations to determine any early signs of local recurrence (12).

For tumors involving only the prepuce, circumcision can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. Tumors involving the glans, glans and prepuce, coronal sulcus, or shaft are best approached with an initial excisional biopsy that includes ample underlying soft tissue to accurately determine the depth of invasion. Tumor stage, the presence of vascular invasion, and the percentage of poorly differentiated cancer each serve as independent prognosticators for inguinal lymph node metastases in penile cancer (13). Once the diagnosis of an invasive penile cancer (T1, T2, and T3) has been made, an extent of disease evaluation is ordered. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with artificial erection have been used to assess the extent of the primary tumors (14). In general, meticulous physical examination is sufficient and accurately determines the depth of invasion into the corpus spongiosum of the glans and even invasion into the corpus carvernosum. Lymphatic invasion has traditionally been evaluated with CT scanning; however, this modality is plagued by low sensitivity as it mainly depends upon nodal size, often not present in the early phase of invasion. Lymphotropic nanoparticles MRI was shown to be very accurate albeit in a very small patient population and lacking any follow-up. Ultrasound in combination with fine needle aspiration biopsy can be useful to detect microscopic invasion at an early stage. The reader, however, is cautioned that only a tumor-positive outcome is reliable. Recent publications have shown the usefulness of a combination of positron emission tomography scan with CT scan in diagnosing regional metastatic disease (15,16). An increased serum calcium level is almost pathognomonic for disseminated disease but is seen only in patients already diagnosed with regional metastases. A full discussion with the patient concerning the degree of penile resection required, the anticipated functional deficit, and the necessary reconstruction required is prudent. Occasionally, plastic surgical consultation is requested if a wide local excision with complex rotational flap coverage is contemplated. If total penectomy is planned, a psychiatric consultation is recommended to be certain that the patient has the emotional capacity to tolerate such a procedure.

While adhering to basic surgical and oncological principles, a tumor-free margin after resection is an essential goal. As in many other primary tumors (e.g., melanoma, prostate cancer, colon cancer, breast cancer), the extent of the negative margin required to secure local tumor control is controversial in penile cancer. If a surgeon were to adhere strictly to the formerly described 2-cm margin, almost no penile cancers would be amenable to a penis-conserving operation. Recent studies have shown that patients treated with margins <2 cm also can obtain long-term recurrence-free survival (17). Hoffman et al. reported, after a mean follow-up of 32.4 months, no local recurrences and one inguinal metastasis in seven patients with T1 or greater tumors with microscopic margins of 10 mm or less, suggesting that a 1-cm margin is sufficient to achieve local tumor control (18). The question of what is the required surgical margin could easily be answered in a contemporary, multi-institutional, randomized trial. It is our practice to send a frozen section of the proximal margin at the time of tumor resection to assure a microscopically negative margin.

TREATMENT OF THE PRIMARY PENILE CARCINOMA

Ablative Techniques

The choice of surgical therapy is dictated by the primary tumor characteristics including size, location, and depth of invasion; and the surgeon’s desire to achieve effective local tumor control while at the same time retaining maximal function of the penis. In situ penile lesions, such as erythroplasia of Queryat and Bowen’s disease, are amenable to local excision, circumcision, tissue ablative techniques such as CO2 and Nd: Yttrium Aluminum Garnet lasers (19,20), and topical 5-fluorouracil cream application (21,22). Occasionally, surgeons may use surgical excision in conjunction with laser therapy to provide an additional 4-mm margin with the intent of achieving a more cosmetically appealing result. With careful case selection and close clinical follow-up, it appears that laser therapy can effectively treat some patients. The effectiveness of laser therapy for overtly invasive penile cancers is uncertain and laser treatment should not be considered an alternative to standard resection. Wound healing after the use of the laser is by secondary intention with full re-epithelialization, usually complete after 8 to 10 weeks. Wound infections are rare following laser therapy. There are also favorable reports of Mohs micrographic surgery for carefully selected in situ and superficially invasive lesions of the glans or shaft (23,24). A specially trained dermatologist performs serial resections until the histological findings are tumor free. If the treating dermatologist or urologist selects an ablative technique to treat in situ lesions of the penis, careful physician follow-up and patient self-examinations to seek early signs of recurrence are essential.

Penile Conservation Techniques

For tumors of the prepuce, circumcision is an effective surgical treatment. Careful examination of the fully exposed glans for evidence of CIS is recommended and a low threshold for additional biopsy should exist. Local excision with adequate underlying soft tissue of invasive penile cancer without partial or total penectomy must be carefully approached. In determining which patient is a candidate for penile conservation procedures, knowledge of the true extent of the local tumor is vital. Physical examination has been shown to be quite reliable in determining the extent of disease and degree of local infiltration into the deeper structures of the penis (25). Operations must be designed to assure negative surgical margins with the goal to achieve a cosmetic result that is acceptable and not cosmetically or functionally worse than a partial penectomy. Intraoperative frozen section must assure negative margins. Local recurrence, an uncommon event following partial or total penectomy, is more common in penile-conserving operations and can be as high as 10% to 15% (26). Patients should be instructed to inspect the remaining epithelium of the glans for recurrence or a new primary, as they remain at lifelong risk for new tumor formation (27).

Most local recurrences can be treated with either a delayed partial amputation or another attempt at penile-conserving surgery. The degree to which local tumor recurrence translates

into degradation in overall survival is not known. Extensive local resections by removing a part of the corona of the glans penis can improve the tumor-free margins and can aid in decreasing local recurrences. Superficial disease covering a large part of the glans can be treated by so-called resurfacing. The epithelial layer of the glans is completely removed and replaced by a skin graft. Excellent results with this approach have been published (28). Resection of a part of the glans is also feasible. This is advisable only if the lesion does not infiltrate deeply into the cavernous tissue and does not extend more than half of the glans. Otherwise, these conservative operations can lead to serious deformation and deviation of the penis during erections with the patient clearly better served with a formal glans removal. In this approach, only the glans is removed instead of standard partial amputation, leading to minimal loss of length of the penis. This defect can be left open for secondary healing, covered with a split thickness skin graft, or partially covered by a mobilized urethra (28). Larger lesions should be managed by a formal partial penectomy (amputation). Verrucous carcinomas, which are of low to intermediate grade and have an exophytic growth pattern, are particularly amenable to local tumor excision (29). If penile conservational techniques are used, it is still necessary to frequently monitor the inguinal nodes that remain at risk for the development of metastatic disease (30).

into degradation in overall survival is not known. Extensive local resections by removing a part of the corona of the glans penis can improve the tumor-free margins and can aid in decreasing local recurrences. Superficial disease covering a large part of the glans can be treated by so-called resurfacing. The epithelial layer of the glans is completely removed and replaced by a skin graft. Excellent results with this approach have been published (28). Resection of a part of the glans is also feasible. This is advisable only if the lesion does not infiltrate deeply into the cavernous tissue and does not extend more than half of the glans. Otherwise, these conservative operations can lead to serious deformation and deviation of the penis during erections with the patient clearly better served with a formal glans removal. In this approach, only the glans is removed instead of standard partial amputation, leading to minimal loss of length of the penis. This defect can be left open for secondary healing, covered with a split thickness skin graft, or partially covered by a mobilized urethra (28). Larger lesions should be managed by a formal partial penectomy (amputation). Verrucous carcinomas, which are of low to intermediate grade and have an exophytic growth pattern, are particularly amenable to local tumor excision (29). If penile conservational techniques are used, it is still necessary to frequently monitor the inguinal nodes that remain at risk for the development of metastatic disease (30).

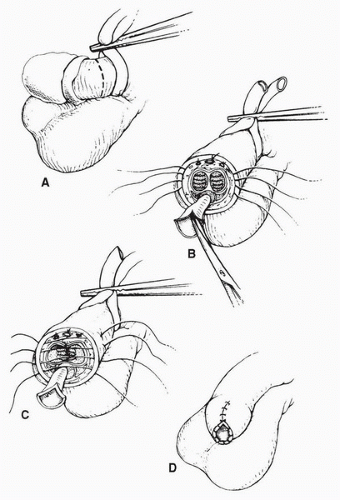

Partial Penectomy

For invasive tumors of the distal penis, partial penectomy with at least a 1-cm margin of resection is recommended (Fig. 47.1). The operation should be designed, if possible, to allow the patient to void in the upright position and without the need to push away the scrotum; otherwise, a perineal urethrostomy should be created. Partial penectomy achieves excellent tumor control with local recurrence rates as low as 6% reported (31). At the time of operation, a latex glove is placed over the primary tumor and distal shaft and is secured to the penis with a suture. A sterile marking pen is used to circumferentially outline the planned incision with care taken to provide at least a 1-cm margin. A medium Penrose drain is placed around the base of the penis and tightened to function as a tourniquet. The incision is circumferentially carried through the skin and Buck’s fascia to the tunic of the corpora. On the dorsum of the penis, the dorsal veins and arteries are individually ligated with absorbable suture. As the resection is carried ventrally, a 1-cm stump urethra is created and spatulated to prevent stenosis of the neourethra. The tunic of corpora cavernosa is closed with 2-0 absorbable sutures that provide hemostasis. The urethra is sutured to the ventral penile skin and a sterile dressing is applied. A recent study of 19 patients whose sexual function was evaluated prior to and after partial penectomy indicated that two thirds of the patients maintained the same level of sexual function and desire as they did prior to partial penectomy. However, only one third maintained the same frequency of intercourse and reported the same degree of satisfaction in their sexual lives. Factors associated with a decline in sexual function included concerns regarding the small penile size, an absence of the glans, and postsurgical complications (32). Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) investigators recently reported the outcome of 34 consecutive patients treated with partial penectomy at their center from 1989 to 2005. Pathology distributions included PIS (N = 1, 3%), P1 (N = 11, 34%), P2 (N = 16, 50%), and P3 (N = 4, 13%). After a mean follow-up of 34 months, overall survival was 56%. Local tumor control was excellent in this series with only one local recurrence reported. Prognostic factors associated with a poor outcome included a poor and moderate tumor differentiation and T stage >1 (33). Kattan et al. combined partial penectomy data on 175 patients from 11 Italian centers to construct a nomogram to predict survival probabilities based on clinical and pathological variables. Important adverse prognostic factors in this study included tumor grade (2 or 3), tumor thickness (>5 mm), tumor emboli present, infiltration of the corporal cavernosa and spongiosum, and regional node involvement. After a median follow-up of 24 months, 57.7% of patients were alive free of disease and 42.3% were dead of disease (34). Taken together, these studies portray invasive penile cancer as an ominous malignancy from the time of partial penectomy.

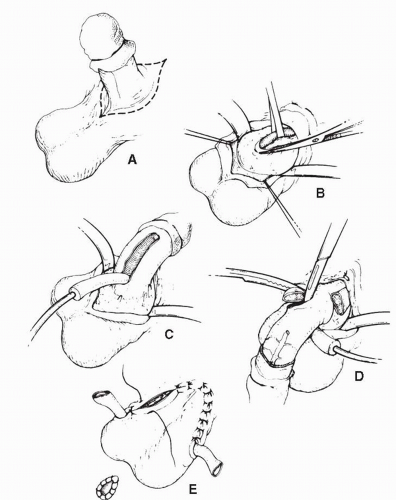

Total Penectomy

For bulky T3 or T4 proximal tumors involving the base of the penis, total penectomy with perineal urethrostomy is done (Fig. 47.2). Total penectomy for proximal tumors that are locally advanced and associated with agonizing local symptoms and bulky regional metastatic disease can provide effective palliation for these patients. Psychiatric input is recommended for patients undergoing total penectomy to be certain that the patient has the necessary emotional capacity to endure the operation and its postoperative implications. During total penectomy, an incision is outlined circumferentially at the base of the penis with extension into the median raphe of the scrotum. At the base of the penis, the suspensory ligament of the penis is identified and divided. The urethra and corpora spongiosum are mobilized from the corpora between clamps and divided. A 2-cm margin of perineal urethra is preserved for construction of a perineal urethrostomy. The urethral remnant

is passed through the scrotum to the midline perineum and the urethrostomy is performed. An 18-French Foley catheter is left in the urethrostomy. In rare cases, the site of attachment of the corpus cavernosum to the pubic bone may need to be resected in order to achieve a clear margin.

is passed through the scrotum to the midline perineum and the urethrostomy is performed. An 18-French Foley catheter is left in the urethrostomy. In rare cases, the site of attachment of the corpus cavernosum to the pubic bone may need to be resected in order to achieve a clear margin.

POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT AND COMPLICATIONS

Early complications after partial or total penectomy include wound infection and hematoma, and stricture of the neomeatus. Stricture of the neomeatus can be managed by simple dilatation or meatotomy. Recurrent strictures may need some form of meatoplasty to correct (i.e., Blandly inlay plasty) or daily patient self catheterization. Needless to say, penectomy can adversely affect a patient’s sexual quality of life. For potent men, erectile function is unaffected; however, intromission may be disturbed. A normal sense of orgasm and ejaculation can persist even after total penectomy.

MANAGEMENT OF REGIONAL LYMPH NODES

General Considerations

Like all squamous cell carcinomas, penile cancer has a propensity for locoregional dissemination, whereas hematogenous dissemination in the absence of lymphatic invasion is uncommon. Metastases in penile carcinoma occur in a sequential manner with tumor cells embolizing through firstechelon regional inguinal nodes and then on to second-echelon deep pelvic nodes (35). Using pooled data from 11 Italian centers involving 175 patients, Ficarra and colleagues generated a nomogram of clinical and pathological features which estimated the risk of inguinal nodal metastases. Features associated with regional metastatic disease at presentation included palpable groin nodes, vascular or lymphatic embolization, and poorly differentiated primary tumors (36). Some surgeons advocate a conservative approach to the groin nodes at the time of presentation in order to avoid the potential morbidity of groin dissection (cellulitis, flap necrosis, lymph edema) without the certainty of a therapeutic dissection. Others advocate an immediate, preemptive surgical approach toward the regional nodes at a point earlier in the course of the disease when a potential survival advantage may be realized, even at the expense of perioperative morbidity or the finding of negative nodes. Approximately 30% to 60% of patients presenting with squamous cell carcinoma of the penis have enlarged lymph nodes in the groin. There are no reported cases of patient with pelvic node involvement without concomitant inguinal node involvement first (37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48).

Nodal metastasis will develop in approximately 20% of patients presenting without any clinical sign of lymphadenopathy, and unfortunately, physical examination and contemporary imaging with CT scan or MRI are not able to reliably detect minimal metastatic nodal disease. The management of this group of patients with invasive penile cancer who are initially node negative remains controversial and may be improved by the evolving use of radionuclide-based lymphoscintigraphy of the sentinel nodes (SNs) or dynamic sentinel lymph node biopsy (DSLNB). This technique has the potential to identify early metastatic disease while at the same time spare the side effects of groin dissection in patients who are node negative. Unlike other genitourinary tumors (e.g., prostate, renal), in which nodal involvement is usually synonymous with incurable disease, nodal metastases in penile cancer are highly curable and therapeutic nihilism is not justified, even in patients with locally advanced lymphatic involvement.

Anatomic Considerations

The regional lymph nodes of the penis are located in the inguinal region (Fig. 47.3) (49,50,51). Some urologic oncologists have divided the inguinal nodes into two groups, a superficial group and a deep group. The superficial nodes are located beneath the subcutaneous fascia and above the fascia lata covering the muscles of the upper leg. Eight to twenty-five nodes can be found. The deep inguinal nodes are those around the fossa ovalis, the opening in the fascia lata in which the saphenous vein drains into the femoral vein. Three to five nodes are usually found there. These nodes intercommunicate with one another and then drain to the pelvic nodes. From a clinical point of view, this distinction is meaningless, because at the time of operation, the superficial inguinal nodes cannot be distinguished from the deep nodes. This point of anatomic confusion has led some surgeons to perform operations that are incomplete and can contribute later to regional nodal recurrence. Therefore, complete groin dissection should be performed in all cases to remove both of these inguinal nodal drainage basins. The most constant and usually largest node is the node found medial to the femoral vein and just underneath the inguinal ligament, the so-called node of Cloquet or Rosenmuller. This node may be missed during either incomplete groin or pelvic dissection and can represent a common site of local recurrence following lymphadenectomy. It is customary to divide the inguinal region into four sections by drawing a horizontal and a vertical line through the point where the saphenous vein drains into the femoral vein. The nodes that are involved primarily in

penile cancer are mainly located in the superomedial segment. However, individual variation exists, and therefore all groin nodes should be removed. The penis drains to both inguinal sides in at least 85% of the patients, as evidenced by lymphangiographic studies, and in 60% of patients as evidenced by studies utilizing lymphoscintigraphy (52,53). The pelvic nodal package consists of nodes around the iliac artery and vein as well as the obturator fossa, above and below the obturator nerve, and contains between 12 and 20 nodes. Crossover from one pelvic nodal basin to the other has not been observed clinically or by lymphoscintigraphy.

penile cancer are mainly located in the superomedial segment. However, individual variation exists, and therefore all groin nodes should be removed. The penis drains to both inguinal sides in at least 85% of the patients, as evidenced by lymphangiographic studies, and in 60% of patients as evidenced by studies utilizing lymphoscintigraphy (52,53). The pelvic nodal package consists of nodes around the iliac artery and vein as well as the obturator fossa, above and below the obturator nerve, and contains between 12 and 20 nodes. Crossover from one pelvic nodal basin to the other has not been observed clinically or by lymphoscintigraphy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree