Fig. 5.1

Patient positioning for inguinal lymph node dissection in the setting of clinically positive nodes. Exposure provided for inguinal and pelvic fields of dissection in addition to harvesting myocutaneous flaps if required

Skin Incision

A Horizontal incision extending medially and laterally two fingerbreadths lateral to and below the pubic tubercle is created for inguinal dissections where the mass does not tent the skin up and there is no ulceration (Fig. 5.2). Alternatively a straight incision extending from the anterior superior iliac spin to pubic tubercle running parallel and 2 cm above the inguinal ligament allows adequate exposure and has been shown to minimize the risk of wound dehiscence and skin necrosis (8 %) [24]. Previously used S and T incisions were associated with higher rates of wound dehiscence and skin necrosis (72 and 82 %, respectively) [25]. If a biopsy was previously obtained, a strip of skin should be excised to include that site. Similarly if the skin is tented up by the mass or skin ulceration is present, the overlying skin should also be excised. Skin flaps should be developed below scarp’s fascia and extended to above the level of the spermatic cord and to the level of the apex of the femoral triangle. Meticulous control of subcutaneous lymphatics is essential to reducing the risk of postoperative lymphocele. The edges of skin flaps should be handled gently.

Fig. 5.2

Skin marked for incision prior to inguinal lymphadenectomy

Surgical Boundaries

Clinically Node Positive Inguinal Field

The surgical boundaries of lymphadenectomy field are the lateral border of adductor longus medially, lateral border of Sartorius muscles laterally, spermatic cord superomedially reaching to 2–3 cm above inguinal ligament with inferior border being apex of femoral triangle with complete removal of muscular fascia, skeletonization of the femoral vessels. The saphenous vein may be spared as this has shown to significantly decrease postoperative edema in similar procedures [26, 27] unless there is bulky disease (Fig. 5.3). In this case of minimal palpable disease resection of the muscular fascia was recently omitted in one series with oncologic control maintained and decreased complications rate [28]. During lymphadenectomy dissection lateral to and below the plane of the femoral artery should be avoided in order to avoid the motor branches of femoral nerve. Superficial branches of femoral artery supplying traveling through the lymphatic packets to supply the overlying subcutaneous tissue are carefully ligated and divided. After completing lymphadenectomy 1-2 closed suction drain are placed to avoid seroma formation. Recently we have covered drain entry sites with patches impregnated with chlorhexidine in order to prevent drain tract infections [29].

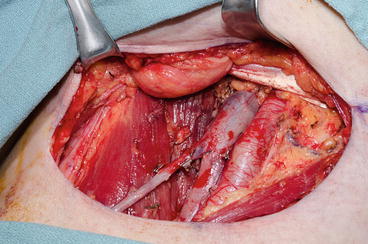

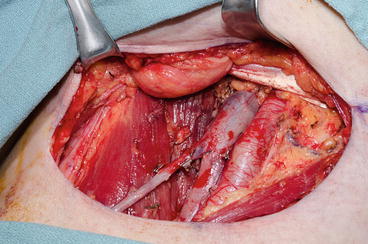

Fig. 5.3

Completed superficial and deep inguinal lymphadenectomy

Contralateral Clinically Node Negative Inguinal Field

A superficial inguinal dissection as described by Bevan-Thomas is performed [25]. Lymphatic tissue above the fascia lata of the thigh is removed between the midpoint of the Sartorius and the adductor longus muscles and 2–3 cm above the inguinal ligament superiorly and inferiorly to 2–3 cm above the apex of the femoral triangle. The saphenous vein was dissected from the nodal packet and preserved (Fig. 5.4). Frozen section analysis of lymph nodes is performed and, if metastases are absent, the procedure is concluded. If metastasis is detected, a complete inguinal dissection is performed. An alternative strategy to stage the clinically negative inguinal field is to perform a dynamic sentinel node biopsy [30] through intradermal, peritumoral injection of a 99mtechnetium-labeled nanocolloid followed by immediate dynamic and static imaging was at 30 min, 90 min, and 2 h. The sentinel node was defined as a node on a direct lymphatic drainage pathway from the primary tumor, and its location(s) were marked on the skin.

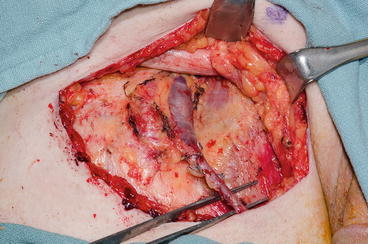

Fig. 5.4

Completed superficial inguinal lymphadenectomy with preservation of the muscular fascia and saphenous vein

Indications for Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection

Pelvic lymphadenectomy is usually preserved for cases with clinically positive pelvic nodes or high-risk pathologically positive inguinal nodes. Given that patients with clinically positive inguinal nodes are at risk to exhibit high-risk pathologic features [9], it is reasonable to perform simultaneous pelvic lymphadenectomy on the ipsilateral side in patients with proven metastases who present with clinically palpable lymph nodes. Lymphadenectomy is usually performed on the ipsilateral side(s) of inguinal nodal metastasis through midline suprapubic incision. In the setting of bilateral inguinal lymph node metastases one recent retrospective study showed that patients with four or more total inguinal nodes were at increased risk for bilateral pelvic metastases and should undergo a bilateral procedure [31]. Given the risk level, we would typically perform a bilateral pelvic dissection among those patients with bilateral inguinal metastases for surgical consolidation as many of these patients would have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to surgery. The boundaries of pelvic lymphadenectomy are the bladder wall medially, genitofemoral nerve laterally, bifurcation of common iliac artery superiorly, and lymph node of Cloquet distally.

Special Consideration for Postchemotherapy Resection of Inguinal Metastases

Surgical Approach and Boundaries

The ultimate goal of neoadjuvant chemotherapy is to improve survival by achieving cytoreduction of metastatic deposits prior to consolidative surgery. Patients who achieve an objective response to systemic therapy are ideal candidates for consolidative surgery. An elliptical skin incision with resection of the area of skin overlying bulky lymph nodes, tumor deposits fixed to the overlying skin, or ulcerated tumors is recommended to ensure complete removal of grossly palpable or visible residual disease with negative surgical margins (Fig. 5.5). Intraoperative frozen sections should be utilized to achieve thus goal. In the setting of bulky disease the saphenous vein and fascia lata are usually resected. Additional procedures occasionally used to ensure local control of advanced disease include excision of the inguinal ligament, spermatic cord and testicle, anterior abdominal wall or femoral vessels with subsequent vein patch or a bypass graft if these structures are grossly invaded by tumor [6].

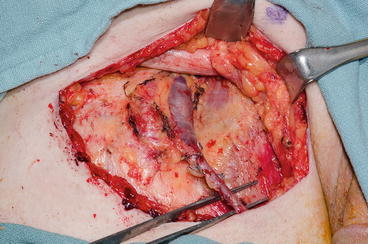

Fig. 5.5

Elliptical incision around mass with initial enbloc resection of skin superficial and deep inguinal nodes subsequent to chemotherapy

Myocutaneous Flap and Skin Graft

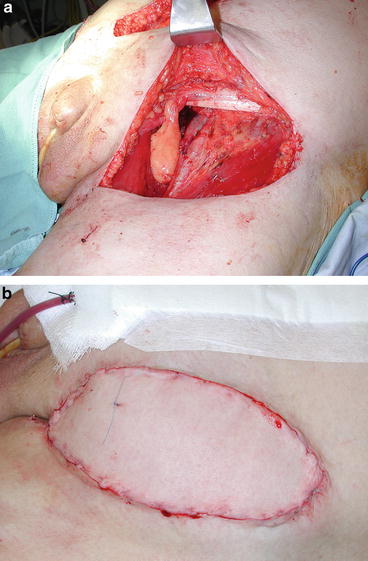

Providing coverage to the skeletonized femoral vessels with vascularized muscle flaps along with bridging skin defects without tension are important steps to decrease postoperative morbidity following ILND by providing for rapid wound healing. A Sartorius muscle flap can be used by dividing the Sartorius muscle from anterior superior iliac spine and transposing it to cover femoral vessels. Other options include the vertical rectus abdominis muscle via raising a flap of muscle with or without the overlying ellipse of skin depending on size of skin defect (Fig. 5.6a, b). The anterolateral thigh musculocutaneus flap is another popular alternative for inguinal reconstruction that may be less morbid than the vertical rectus flap.

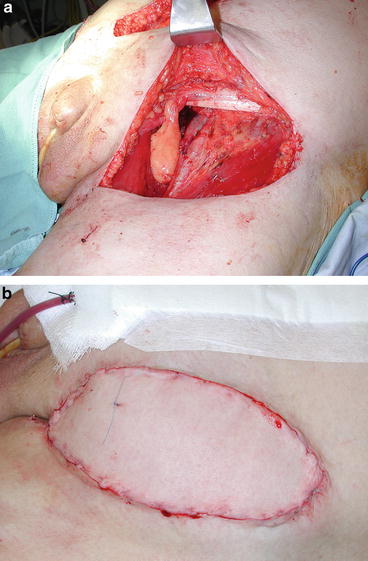

Fig. 5.6

(a) Inguinal tissue defect subsequent to postchemotherapy inguinal lymph node dissection. (b) Vertical rectus myocutaneous flap reconstruction

The above surgical considerations highlight the importance of preoperative planning when considering surgical consolidation among patients with advanced inguinal metastases. Multidisciplinary input from urologic, plastic, and vascular surgical teams helps insure optimal care for these patients.

Postoperative Care

Postoperative care for patients who undergo ILND for penile cancer is of specific importance to maximize quality of life and functional return. Patients with no limitations on activity based on the type of procedure performed should be encouraged to ambulate as early as possible. Support hose and sequential compression devices are utilized as standard along with low-molecular-weight heparin. Based upon the need for rotational muscular flaps certain positions may need to be avoided such as prolonged periods with the hips flexed at 90°. Drains are typically kept until drainage is less than 30–50 cm3 per 24 h for 2 days after ambulation, and antibiotics are discontinued once all drains are removed. The same principle applies for pelvic drains in the setting of pelvic lymphadenectomy. A physical therapy consult once all drains are removed is helpful to evaluate patients and prescribe specific strategies to prevent lymphedema. Typically patients are measured for fitted stockings and taught massage techniques to reduce the volume of fluid in the extremities. Early prophylactic intervention is preferred to waiting for lymphedema to develop and then subsequent treatment.

Postoperative Complications

Early postoperative complications were reported to be as high as 55.4 % in a recent study which analyzed data from four tertiary referral centers in United States and Europe [32]. However 65.7 % of these complications were deemed minor according to the Clavien-Dindo system. Wound infection (34.8 %) seroma (26.5 %), lymphocele (10.4 %) (requiring no intervention and wound dehiscence (7.2) were the most frequent minor complications while wound infection (requiring iv antibiotic) (22.1 %), skin flap necrosis (12.7 %), lymphocele (requiring intervention) (3.3), and no-healing wound (2.2 %) were the most frequent major complications. In multivariate analysis number of lymph nodes removed was an independent predictor of experiencing any complication, while the median number of lymph nodes removed was an independent predictor of major complications. The American Joint Committee on Cancer stage was an independent predictor of all wound infections. While the patient’s age, ILND with Sartorius flap transposition, and surgery performed before the year 2008 were independent predictors of major wound infections.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree