Chapter 6 Supplementary techniques including blood parasite diagnosis

Tests for the acute-phase response

Inflammatory response to tissue injury includes alteration in serum protein concentration, especially increases in fibrinogen, haptoglobin, caeruloplasmin, immunoglobulins (Ig) and C-reactive protein (CRP), and decrease in albumin. The changes occur in acute infection, during active phases of chronic inflammation, with malignancy, in acute tissue damage (e.g. following acute myocardial infarction) with physical injury. Measurement of the acute-phase response is a helpful indicator of the presence and extent of inflammation or tissue damage and response to treatment. The usual tests are estimation of CRP and measurement of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); some studies have suggested that plasma viscosity is also a useful indicator, but there is debate on the relative value of theses tests.1,2

Kits that are sensitive and precise are available for CRP assay; small increases in serum levels of CRP can often be detected before any clinical features become apparent, whereas as a tissue-damaging process resolves, the serum level rapidly decreases to within the normal range (<5 mg/l). The ESR is slower to respond to acute disease activity and it is insensitive to small changes in disease activity. It is less specific than CRP because it is also influenced by immunoglobulins (which are not acute-phase reactants) and by anaemia. Moreover, because the rate of change of ESR is slower than that of CRP, it rarely reflects the current disease activity and clinical state of the patient as closely as the CRP. The ESR is a useful screening test, and the conventional manual ESR method is simple, cheap and not dependent on power supply, thus making it suitable for point-of-care (near-patient) testing. It is recommended that, in clinical practice, both tests should be carried out in tandem.3 Because CRP assay is a biochemical test usually performed in the clinical chemistry laboratory, it will not be discussed further here.

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate

The method for measuring the ESR recommended by the International Council for Standardization in Haematology (ICSH)4 and also by various national authorities5 is based on that of Westergren, who developed the test in 1921 for studying patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. ESR is the measurement of the sedimentation of red cells in diluted blood after standing for 1 h in an open-ended glass tube of 30 cm length mounted vertically on a stand.

Conventional Westergren Method

Method

The method described below, originally described by the International Council for Standardization in Haematology (ICSH)4 and now adopted by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) as its approved method,5 is intended to provide a reference method for verifying the reliability of any modification of the test.

Range in health

The mean values and the upper limit for 95% of normal adults are given in Table 6.1. There is a progressive increase with age, but it is difficult to define a strictly healthy population for determining normal values in individuals older than 70 years.6 In the newborn, the ESR is usually low. In childhood and adolescence, it is the same as for normal men with no differences between boys and girls. It is increased in pregnancy, especially in the later stages, and independent of anaemia;7 this is due to the physiological effect of haemodilution (an increase in the plasma volume)

Table 6.1 Erythrocyte sedimentation rate ranges in health

| Age range (years) | ESR mean MM IN 1 H |

|---|---|

| 10–19 | 8 |

| 20–29 | 10.8 |

| 30–39 | 10.4 |

| 40–49 | 13.6 |

| 50–59 | 14.2 |

| 60–69 | 16 |

| 70–79 | 16.5 |

| 80–91 | 15.8 |

| Pregnancy | |

| Early gestation | 48 (62 if anaemic) |

| Later gestation | 70 (95 if anaemic) |

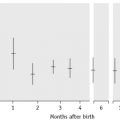

In the newborn, the ESR has been reported to be 0–2 mm in 1 h, increasing to 4 mm in 1 h at 1 week, up to 17 mm in 1 h by day 14, and then 10–20 mm in 1 h for both girls and boys, until puberty.8 However, as the studies in infants were obtained by the capillary method, they are not strictly comparable to the Westergren method.

Modified methods

Time

Sedimentation is measured after aggregation has occurred and before the cells start to pack, usually at 18–24 min. From the rate during this time period the sedimentation that would have occurred at 60 min is derived and converted to the conventional ESR equivalent by an algorithm.9

Sloping tube

Red cells sediment more quickly when streaming down the wall of a sloped tube. This phenomenon has been incorporated into automated systems in which the end-point is read after 20 min with the tube held at an angle of 18° from the vertical.10 Incorporating a low-speed centrifugation step (approx. 800 rpm) in this automated method reduces the end-point time further.11 These have been shown to give results comparable to the conventional method.

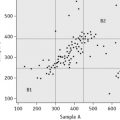

Quality Control

The standardized method can be used as a quality-control procedure for routine tests or alternatively stabilized whole blood preparations which are now available are suitable as a daily control for use with automated systems (e.g. ESR-Chex).12 Three or four specimens of EDTA blood kept at 4°C will also serve as a control on the following day.

Another control procedure is to calculate the daily cumulative mean, which is relatively stable when at least 100 specimens are tested each day in a consistent setting (see Chapter 25). A coefficient of variation of <15% between daily sets appears to be a satisfactory index for monitoring instrument performance.13

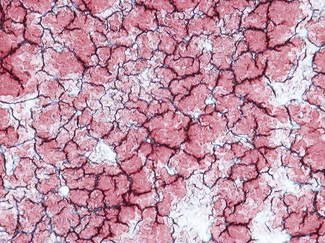

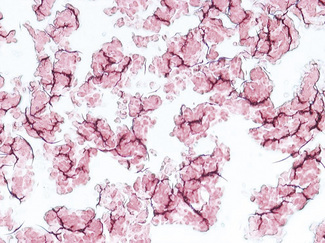

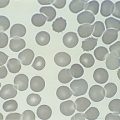

Semiquantitative Slide Method

Enhanced red cell adhesion/aggregation can be demonstrated by allowing a drop of citrated blood to dry on a slide. An estimate of the amount of cell aggregation on the film by image analysis provides a semiquantitative measure of the acute-phase response that appears to correlate with the ESR.14 Based on this principle, serial microscopic images of red cells aggregating on a glass slide taken every 30 s for 5 min can distinguish a normal ESR from a high value (Figs 6.1, 6.2). The images demonstrate greater spacing of cells in blood with higher ESR values compared with blood with lower ESR values.

Mechanism of Erythrocyte Sedimentation

An elevated ESR occurs as an early feature in myocardial infarction.15 Although a normal ESR cannot be taken to exclude the presence of organic disease, the vast majority of acute or chronic infections and most neoplastic and degenerative diseases are associated with changes in the plasma proteins that lead to an acceleration of sedimentation. An increased ESR in subjects who are HIV seropositive seems to be an early predictive marker of progression toward acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).16 The ESR is less helpful in countries where chronic diseases are rife; however, one study has shown that very high ESRs (higher than 100 mm/h) have a specificity of 0.99 and a positive predictive value of 0.9 for an acute or chronic infection.17 The ESR is influenced by age, stage of the menstrual cycle and medications taken (corticosteroids, contraceptive pills). It is especially low (0–1 mm) in polycythaemia, hypofibrinogenaemia and congestive cardiac failure and when there are abnormalities of the red cells such as poikilocytosis, spherocytosis, or sickle cells. In cases of performance-enhancing drug intake by athletes (discussed below) the ESR values are generally lower than the usual value for the individual and as a result of the increase in haemoglobin (i.e. the effect of secondary polycythaemia).

Plasma Viscosity

The ESR and plasma viscosity generally increase in parallel with each other.1 Plasma viscosity is, however, primarily dependent on the concentration of plasma proteins, especially fibrinogen, and it is not affected by anaemia. Changes in the ESR may lag behind changes in plasma viscosity by 24–48 h, and viscosity seems to reflect the clinical severity of disease more closely than does the ESR.18

There are several types of viscometers, including rotational and capillary types that are suitable for routine use1 and, as for ESR methods, automated closed-tube methods are available.19 The main use of plasma viscosity is in the investigation of individuals with suspected hyperviscosity, myeloma and macroglobulinaemia. In conjunction with the ESR and CRP, the plasma viscosity can be used as a marker for inflammation. The viscosity test should be carried out as described in the instruction manual for the particular instrument used.

Reference Values

Each laboratory should establish its own reference values for plasma viscosity. As a general guide, ICSH has recorded that with the Harkness capillary viscometer normal plasma has a viscosity of 1.16–1.33 mPa/s (if expressed in poise (P), 1 cP = 1 mPa/s) at 37°C and 1.50–1.72 mPa/s at 25°C.20 Plasma viscosity is lower in the newborn (0.98–1.25 mPa/s at 37°C), increasing to adult values by the 3rd year; it is slightly higher in old age. There are no significant differences in plasma viscosity between men and women or in pregnancy. It is remarkably constant in health, with little or no diurnal variation, and it is not affected by exercise. A change of only 0.03–0.05 mPa/s is thus likely to be clinically significant.

Whole blood viscosity

Guidelines for measuring blood viscosity and red cell deformability by standardized methods have been published.21 Rotational and capillary viscometers are suitable for measuring blood viscosity; deformability can be measured by recording the rate at which red cells in suspension pass through a filter with pores 3–5 mm in diameter.

Heterophile antibodies in serum: diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis

Infectious mononucleosis (IM) is caused by Epstein–Barr virus.22 The immune response that develops in response to virus-infected cells includes not only antibodies to viral antigens but also characteristic heterophile antibodies. Before the nature of this reaction was understood, Paul and Bunnell23 demonstrated the antibodies as agglutinins directed against sheep red cells. They are, in fact, not specific for sheep red cells but also react with horse and ox, but not human, red cells. They are IgM globulins, which are immunologically related to, but distinct from, antibodies that occur in response to the Forssman antigens. The latter are widely spread in animal tissue; they occur at low titre in healthy individuals and at high titre in serum sickness and in some leukaemias and lymphomas.24,25 In these non-IM conditions, the antibody can be absorbed out by guinea pig cells. Thus, for the diagnosis of IM, it is necessary to demonstrate that the antibody present has the characters of the Paul–Bunnell antibody (i.e. it is absorbed by ox red cells but not by guinea pig kidney). This is the basis of the absorption tests for IM (‘monospot’ test). Immunofluorescent antibody tests have been developed to distinguish the IgM antibody, which occurs at high titre in the early phase of IM and diminishes during convalescence, from the IgG antibody, which persists at high titre for years after infection26,27 and which also occurs in the non-IM infections.22,28

Screening Tests for Infectious Mononucleosis

The reagents for IM screening are available commercially in diagnostic kits from several manufacturers. Guinea pig cells can be also be manufactured locally as described in previous editions. Some kits are based on agglutination of stabilized horse red cells or antigen-coated latex particles to which IM antibody binds. An extensive evaluation of 14 slide tests for the UK Medical Devices Agency (MDA), showed them to have a sensitivity between 0.87 and 1.00 and specificity of 0.97 to 1.00, with an overall accuracy (positive and negative) in the order of 91–100%.25 False-positive reactions have been reported in malaria, toxoplasmosis, and cytomegalovirus infection; autoimmune diseases; and even occasionally without any apparent underlying disease.29,30 False-negative reactions occur if the test is carried out before the level of heterophile antibody has increased or conversely when it has decreased. False-negative reactions may also occur in the very young and the very old. In the UK MDA study the best performance was obtained with the Clearview test (Unipath

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree