Patient Position and Exposure

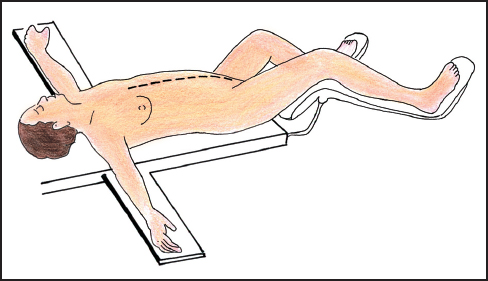

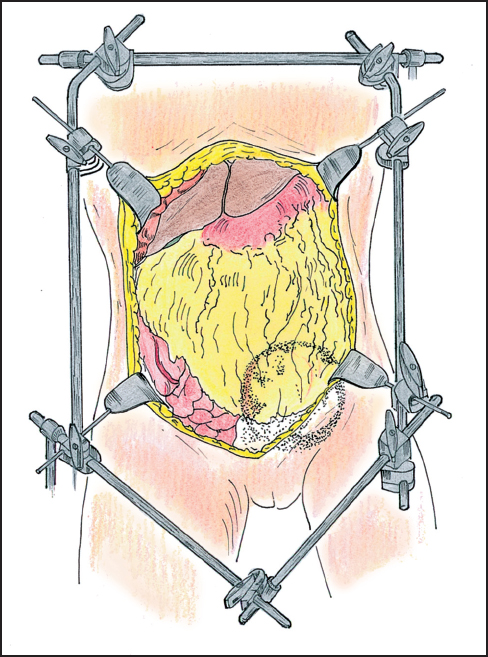

One must be prepared for a major surgical event with wide abdominal and pelvic exposure in order to achieve the greatest incidence of success. In most patients extensive abdominal dissections must be performed before the pelvic malignancy can be approached. Positioning of the patients so that surgery through the perineum is possible is often indicated (Fig. 11.1). Long abdominal incisions from xiphoid to pubis are usually required and self-retraining retractors that can expose the entire abdomen and pelvis are often indicated (Fig. 11.2). Skin is prepared so that a thoracoabdominal or an abdominoinguinal incision can be performed if required.

One must always be cognizant of the surgeon’s needs to think three-dimensionally in approaching these deep-seated malignancies. This helps to avoid inadvertent damage to vital structures. In order to build within the surgeon’s mind a three-dimensional appreciation of the vital structures in the abdomen, one should always strive to open the abdomen and set up the self-retaining retractor system in the same way. This means that the iliac arteries and veins, the ureters,etc., have a particular spatial orientation within the surgeon’s mind. A standard exposure of the abdominal cavity through a midline incision with uniform placement of the self-retaining retractor can assist the surgeon in his goal of avoiding hemorrhage and inadvertent damage to vital structures.

Fig 11.1 Patient position for surgical treatment of abdominal and pelvic sarcoma.

Fig 11.2 Exposure for abdominal and pelvic surgery using a self-retaining retractor.

Reoperative Surgery

Reoperative Surgery

Frequently in a tertiary referral center, one sees patients with pelvic malignancy after one or more prior attempts at the surgical removal of the cancer.7 In these patients, removal of the recurrent cancer may be delayed many hours because exposure of the tumor mass may be difficult and time consuming. Cancer within the old abdominal incision, extensive abdominal adhesions, tumor that has regrown within scar tissue, fibrosis that accompanies the local recurrence of cancer, and alterations of normal anatomy by prior reconstructions may require patience and advanced technical skills to bring about the complete exposure of the malignant process.8,9

Always Open Old Incisions

Always Open Old Incisions

Even though opening an old incision is difficult and may result in small or large bowel damage, rarely should a new incision be made into the abdomen in performing reoperative surgery. New incisions will cause additional adhesions and may severely jeopardize primary wound healing of the abdominal wall. It is usually necessary to excise old incisions because they can contain malignant foci embedded within the scar tissue. The surgeon routinely plans to completely excise the old scar tissue in the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and fascia as the abdomen is opened.

Safe Entry into the Abdominal Cavity

Safe Entry into the Abdominal Cavity

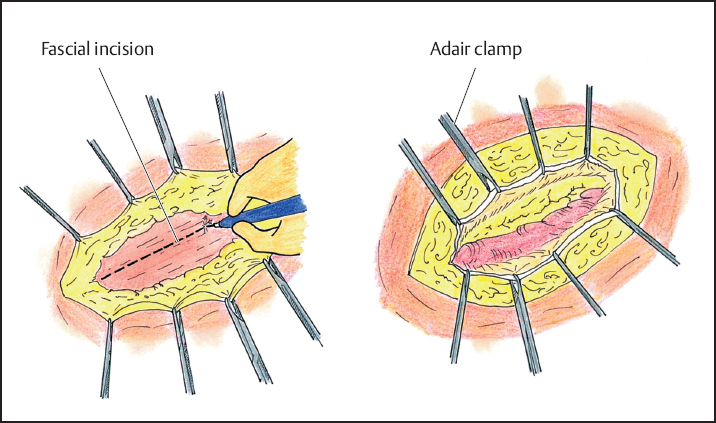

Opening the abdomen without damage to the small bowel in a patient who has had several prior surgical procedures in order to remove a pelvic malignancy may be difficult and time consuming. One should realize that entering an abdomen with multiple adhesions requires a strong upward traction of the abdominal wall in order to avoid inadvertent small bowel or large bowel enterotomy. Adair clamps should be used to pull up on the skin or abdominal fascia as the abdomen is entered (Fig. 11.3). Pushing down in order to spread the scar that makes up the old abdominal incision is to be avoided.

Fig 11.3 Opening the old abdominal incision by pulling upward on skin (left) or fascial edges (right) using Adair clamps

Surgical Approach to Intraabdominal Adhesions

Surgical Approach to Intraabdominal Adhesions

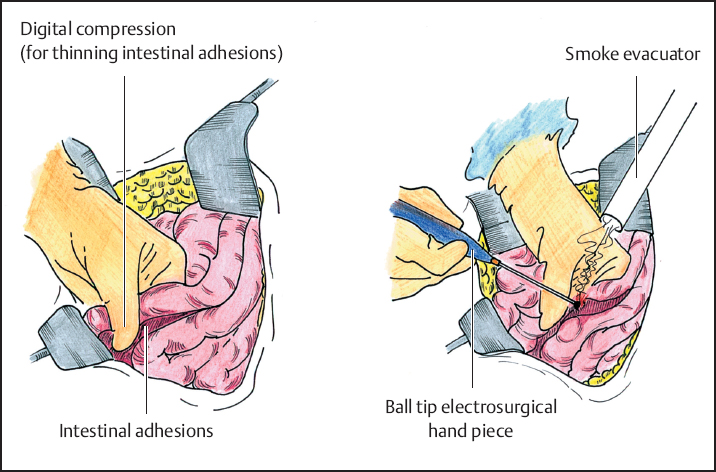

Small bowel adhesions present a special problem in management. Small bowel enterotomy resulting in fistula formation after reoperative procedures is a major problem that will be encountered. The experienced surgeon will adhere to several principles in lysing small bowel adhesions:

- Tactile sense should be added to visual perceptions in the dissection of the adhesions (Fig. 11.4). This requires the use of ball-tipped electrosurgery. Fibrous adhesions and fat are morseled between the thumb and index finger of the nondominant hand. Important pressure may need to be applied. Ball-tip electrosurgery electroevaporates (carbonizes) residual tissue on the small bowel surface as this tissue is splayed out on the middle finger.

- Absolute hemostasis must be maintained at all times in dissecting small bowel adhesions. One must realize that bleeding that occurs while dissecting small bowel adhesions indicates that the surgeon is in an improper plane. Fat with blood vessels contained within should only be divided in the abdomen and pelvis when the surgeon is transecting omentum, retroperitoneal structures, or perirectal fat. Bleeding that is encountered while taking down intestinal adhesions indicates that the surgeon is entering into the small or large bowel mesentery and this should be avoided.

- I Large volume saline irrigation should be used frequently. Even small amounts of blood can interfere with adequate visualization of delicate tissue planes for further dissection. If absolute hemostasis is combined with frequent irrigation the translucent nature of the tissues will be preserved throughout the dissectionand inadvertent damage to vital structures or to blood vessels should not occur.

- Fat or scar tissue should never be left behind on small bowel surfaces. This scar tissue may frequently contain entrapped tumor cells. If miscellaneous tissues remain on bowel surfaces, confusion may arise in subsequent dissection. There is only one small bowel surface that contains fat on its antimesenteric border, and this is at the terminal ileum.

- Broad traction (as compared to point traction) should be maintained. The small bowel should be splayed out so that the plane of dissection for the ball-tipped electrosurgical handpiece is clearly visualized.

- I Complete removal is the rule when dealing with intraabdominal adhesions. Generally, all adhesions must be lysed and then resected. The complete anatomy of the large and small bowel is visualized prior to beginning the definitive resection.

In the reoperative setting opening old abdominal incisions and the dissection of abdominal adhesions without damage to the bowel must be mastered by the cancer surgeon. Use of electrosurgery with the ball-tip is indicated because it allows tactile sensations to be added to visual perceptions in the dissection. This makes the process safer and certainly expedites the opening of the abdomen, lysis of intraabdominal adhesions, and clarification of the dissection required for radical excision of the recurrent malignancy.

Fig 11.4 Dividing abdominal adhesions. Pressure between thumb and index finger is used to thin out the adhesion between two loops of small bowel. Ball-tip electrosurgery is used to divide and evaporate the adhesion (right). Division of adherent tissue on small bowel surfaces on the middle finger of the nondominant hand adds tactile to visual perceptions (left).

Abdominal and Pelvic Exploration

Abdominal and Pelvic Exploration

In performing surgery on patients with advanced pelvic malignancy, the complete (both visceral and parietal) abdominal and pelvic surfaces must be visually inspected to look for tumor deposits.10 This means that all abdominal adhesions must be lysed as part of the complete exploration. The omentum, likewise, must be dissected free and inspected to determine whether it contains sarcoma nodules. The presence of carcinomatosis or sarcomatosis is of great importance in the decision-making process in patients undergoing reoperative surgery. If there was tumor spillage at the time of earlier surgery, then implants are expected to be revealed with the abdominal exploration.

If the patient can be made disease-free in the presence of peritoneal surface spread, then the benefits of intraperitoneal chemotherapy should be considered. The adhesions are completely dissected as part of the oncologic procedure to allow uniform distribution of chemotherapy. From a purely technical point of view, complete lysis and resection of all abdominal adhesions is not an absolutely necessary step in complete resection of abdominal and pelvic sarcoma. However, from an oncologic perspective, complete lysis and resection of all adhesions followed by early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy is an absolute requirement for the prevention of subsequent carcinomatosis or sarcomatosis.

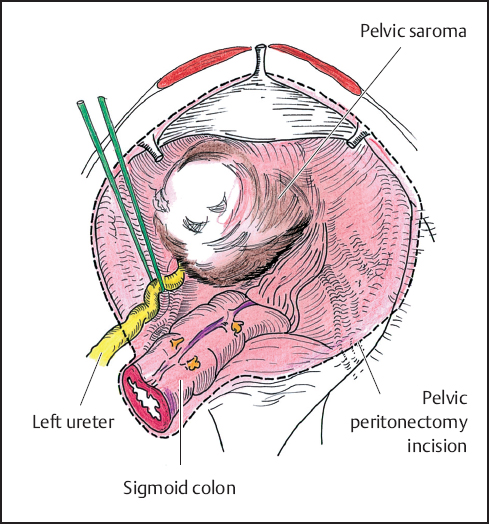

Fig 11.5 Pelvic peritonectomy is useful to completely excise a pelvic sarcoma, especially if there is sarcomatosis or recurrent tumor at the resection site.

Centripetal Dissection

Centripetal Dissection

“Centripetal dissection” requires repeated dissection in a circular manner around the principal tumor mass. Dissection continues at a particular site only if there is clear visualization of the operative field. The surgeon should repeatedly circle the tumor mass completing the superficial dissections before the more difficult deep ones are attempted (“Do what is easy first.”). He moves around and around the cancer, only working where he has good exposure, where he is loosing no blood, where he is unlikely to damage vital structures, and where the dissection is proceeding with a clear margin. If any of these criteria for safe progress are not met, the surgeon should move his dissection to a different area. The tumor mass is generally circled many times prior to delivering the intact specimen. In summary, centripetal dissection avoids at all times major hemorrhage or damage to vital structures by limiting dissection to areas that allow clear visualization of the operative field. A circular pattern of progressively deeper dissection results from this approach.

Avoid Trauma to the Tumor Surface Especially with Sarcoma

Avoid Trauma to the Tumor Surface Especially with Sarcoma

In the removal of pelvic sarcomas, one must always be aware of possible major hemorrhage from surface vasculature. Blood vessels in the sarcoma pseudocapsule are large, thin-walled, easily traumatized, and difficult to control once bleeding has occurred. Once one disrupts the tumor vasculature, bleeding is likely to be brisk. One should dissect away from the tumor in normal tissues as much as possible. If strong traction on the sarcoma mass is required, this should be allowed only after all other dissection is completed.

Maintain Hemostasis throughout the Procedure

Maintain Hemostasis throughout the Procedure

One must always pay continuous attention to hemostasis, because inadequate hemostasis interferes with subsequent exposure. Blood in the operative field obscures the identification of additional bleeding points. Hemostasis must be achieved with electrocoagulation, ligatures, or clips as the dissection proceeds. The translucent nature of the tissues within the surgical field can be maintained by meticulous hemostasis and frequent irrigation.

Use of Peritonectomy Procedures

Use of Peritonectomy Procedures

Very often in the reoperative setting the surgeon must be willing to dissect in a preperitoneal or retroperitoneal plane rather than moving through the peritoneal cavity itself. Peritonectomy procedures go beneath scar tissue to achieve a negative margin of resection.11–15 Tumor at a resection site will almost always be beneath the peritoneal surface. An effective way to safely approach these recurrent tumor masses is by going beneath the peritoneal layer into a deeper plane away from the tumor mass (Fig. 11.5). Pelvic peritonectomy should be pursued in the reoperative setting with recurrence at the resection site and for invasive tumors being resected for the first time.

Utilize “Piecemeal” Excision

Utilize “Piecemeal” Excision

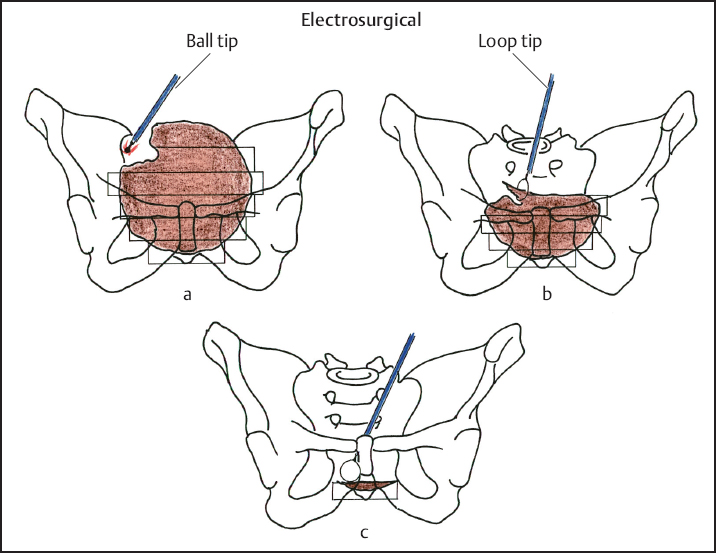

Often freeing up of a pelvic tumor mass will progressively obscure the plane of dissection. This will compromise the safety of subsequent dissection because of inadequate visualization, inadequate hemostasis, or an unnecessarily narrow margin of excision. Large tumor masses will become more and more difficult to extirpate as the dissection proceeds. As the anatomic site for further dissection is more deeply obscured by a large mass of tumor, the surgeon may be tempted to resort to dangerous blunt pelvic dissection to continue resection. In this situation, piecemeal excision of the sarcoma is an important part of the operative procedure. Superficial components of the tumor may be removed prior to continuing the dissection of a deeper aspect of the tumor. Piecemeal excision using an electrosurgical loop on pure cut is usually the best way to remove portions of the tumor prior to its complete resection (Fig. 11.6). Piecemeal excision of a large tumor mass is much safer for the patient than is dissection with inadequate visualization. However, one must do everything possible to guard against the intraabdominal dissemination of cancer cells. The surrounding structures must be protected with laparotomy pads and towels. The electrosurgical loop at high voltage on pure cut removes fillets of tumor with minimal spillage of viable malignant cells. After each level of tumor is resected, thorough irrigation of the operative field is required.

Fig 11.6 Piecemeal excision of abdominal or pelvic sarcoma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree