The stomach, which begins at the gastroesophageal (G-E) junction and ends at the pylorus, is usually apportioned into three parts. The cranial portion is the fundus (cardia). A plane passing through the incisura angularis on the lesser curvature divides the remainder of the stomach into the body and the pyloric portion (antrum).

There is variable visceral peritoneal covering at the most proximal portion of the G-E junction.

The stomach’s vascular supply is derived from the celiac axis, which originates at or below T12 in about 75% of patients, and at or above L1 in 25% of patients.

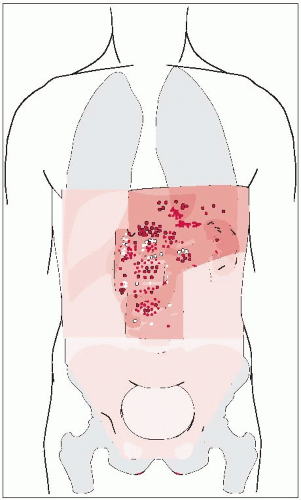

Lymphatic drainage follows the arterial supply. Although most lymphatics drain ultimately to the celiac nodal area, lymph drainage sites can include the splenic hilum, suprapancreatic nodal groups, porta hepatis, and gastroduodenal areas.

Risk factors implicated include smoked and salted foods, low intake of fruit and vegetables, low socioeconomic level, and decreased use of refrigeration (1).

Gastric ulcer per se carries no increased risk, although previous distal gastrotomy for benign disease confers a 1.5- to 3.0-fold relative risk of developing gastric cancer with a latency period of 15 to 20 years (20).

Helicobacter pylori is associated with a 3 to 6 times greater risk of gastric cancer than in those without infection. The increased association of H. pylori appears confined to those with distal gastric cancer and intestinal-type malignancy (7).

Cancer of the stomach may extend directly into the omenta, pancreas, diaphragm, transverse colon or mesocolon, and duodenum.

Peritoneal contamination is possible after a lesion extends beyond the gastric wall to a free peritoneal (serosal) surface (13).

The liver and lungs are common sites of distant metastases for G-E junction lesions. With gastric lesions that do not extend to the esophagus, the initial site of distant metastasis is usually the liver.

It is difficult to perform a complete node dissection because of the numerous pathways of lymphatic drainage from the stomach (Fig. 26-1). Initial drainage is to lymph nodes along the lesser and greater curvatures (gastric and gastroepiploic nodes), but drainage continues to the celiac axis (porta hepatis, splenic suprapancreatic, and pancreaticoduodenal nodes), adjacent para-aortics, and distal paraesophageal system.

Diagnosis is usually confirmed by upper gastrointestinal radiography and endoscopy. Doublecontrast x-ray films may reveal small lesions limited to the inner layers of the gastric wall.

Endoscopy with direct vision, cytology, and biopsy yields the diagnosis in 90% or more of exophytic lesions.

TABLE 26-1 Staging Systems for Gastric Carcinoma

Modified

Astler-Coller

TNMa

Characteristics

Stage A

T1N0

Nodes negative; lesion limited to mucosa

Stage B1

T2N0

Nodes negative; extension of lesion through mucosa but still within gastric wall

Stage B2b

T3N0

Nodes negative; extension through entire wall (including serosa if present) with or without invasion of surrounding tissues or organs

Stage C1

T2N1-2

Nodes positive; lesion limited to wall

Stage C2b

T3N1-2

Nodes positive; extension of lesion through entire wall (including serosa)

aT4, diffuse involvement of entire thickness of stomach wall (linitis plastica); N1, perigastric nodes in immediate vicinity of primary tumor; N2, involvement of perigastric nodes at a distance from primary tumor or on both curvatures.

bSeparate notation is made regarding degree of extension through wall: m, microscopic only; g, gross extension confirmed by microscopy; B3 + C3, adherence to or invasion of surrounding organs or structures; both T3 and M1 in TNM system.

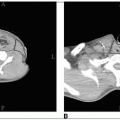

Abdominal computed tomography is useful in determining the abdominal extent of disease.

Endoscopic ultrasound is the most accurate method of preoperatively assessing tumor (T) and nodal (N) stage.

Adenocarcinoma accounts for 90% to 95% of all gastric malignancies.

Lymphoma, usually with unfavorable histology, is the second most common malignancy.

The most important prognostic indicator is tumor extent.

Lymph node involvement is also important, as are the number and location of nodes affected.

Operative attempts are highly successful if disease is limited to the mucosa, but the incidence of such early lesions at diagnosis is less than 5% in most United States series.

The preferred treatment for gastric carcinoma, especially for lesions arising in the body or antrum, is radical subtotal resection, if satisfactory margins can be achieved. This operation removes approximately 80% of the stomach with the node-bearing tissue, the gastrohepatic

and gastrocolic omenta, and the first portion of the duodenum. Total gastrectomy does not offer improved locoregional control, and leads to increased morbidity and mortality. Proximal lesions, however, often prompt total gastrectomy if 5-cm margins are unachievable.

The propensity for gastric carcinoma to spread by means of submucosal lymphatics suggests that a 5-cm margin of normal tissue proximally and distally may be optimal.

The increasing incidence of T3 and T4 G-E tumors has resulted in a greater incidence of microscopically positive radial margins. The perigastric tissue surrounding the G-E junction and distal esophagus has no serosa, so lesions that extend to the margin at this site often represent “true” positive margins.

The optimal extent of lymph node dissection is controversial. Two prospective randomized trials of lymphadenectomies showed no survival advantage with more extensive lymph node dissection (3, 4, 10, 14). D1 dissection removes only the perigastric nodal areas within 3 cm of the stomach; D2 procedures also remove celiac axis, splenic artery, and splenic hilar nodes, omentum, and removal of all perigastric nodes further than 3 cm of the stomach.

Endoscopic laser surgery may also be used to treat patients with early gastric cancer in the setting of patients who are deemed inoperable secondary to medical comorbidities.

Disease progression within the abdomen is approximately 57%. Abdominal treatment should also address peritoneal seeding, which occurs in 23% to 43% of postgastrectomy patients (20).

The U.S. GI Intergroup Gastric Adjuvant Trial (INT 0116) evaluated the benefit of adjuvant combined modality therapy in the postoperative setting for patients with disease extension through the gastric wall and/or nodes positive for tumor. Five hundred and sixty-six patients with Stage IB-IVM0 disease underwent R0 resection of adenocarcinoma of the stomach and were randomized to receiving surgery plus postoperative chemoradiation or surgery alone. Combined modality therapy increased median survival to 36 months compared to 27 months in the surgery-only arm (p

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree