Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) represents the most common lymphoid malignancy in adults, with a median age of 60 to 70 years. Clinical behavior is usually rapidly aggressive, with extranodal involvement in 40% of cases. Chemoimmunotherapy administered every 21 days is still the standard of care in the advanced stage. Optimization of frontline therapy and the amelioration of salvage strategies remain the most important targets in the treatment of patients with DLBCL. Novel drugs directed to specific molecular targets have been introduced as single agents or in addition to standard chemoimmunotherapy for the treatment of DLBCL.

Key points

- •

Identification of prognostic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) subgroups, standard treatment with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and prednisone (R-CHOP), role of high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplant, addition of novel biologic drugs to R-CHOP therapy.

- •

R-CHOP 21 is still the standard treatment in both low-risk and high-risk advanced-stage DLBCL.

- •

Approximately 30% to 40% of patients fail R-CHOP, mainly not achieving complete response (CR) or with early relapse.

- •

An essential step to improve the outcomes of these patients is to increase the CR rate.

- •

A better recognition of unfavorable DLBCL subtypes is necessary, in order to personalize the treatment with targeted and tailored approaches.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common lymphoid malignancy in adults, representing almost 35% to 40% of lymphomas in Western countries. The estimated incidence is 7 to 8 cases per 100,000 per year and has doubled in recent decades. The peak incidence of DLBCL is in the sixth decade.

DLBCL shows a diffuse pattern of proliferation, with high proliferation rate of atypical large cells with vesicular nuclei. There are different histologic subtypes of DLBCL with peculiar features, including immunoblastic lymphoma, T-cell/histiocyte rich, primary cutaneous DLBCL leg-type, and Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL of the elderly.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common lymphoid malignancy in adults, representing almost 35% to 40% of lymphomas in Western countries. The estimated incidence is 7 to 8 cases per 100,000 per year and has doubled in recent decades. The peak incidence of DLBCL is in the sixth decade.

DLBCL shows a diffuse pattern of proliferation, with high proliferation rate of atypical large cells with vesicular nuclei. There are different histologic subtypes of DLBCL with peculiar features, including immunoblastic lymphoma, T-cell/histiocyte rich, primary cutaneous DLBCL leg-type, and Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL of the elderly.

Patient evaluation overview

Surgical excision or incision tumor biopsy is required for histology definition and DLBCL diagnosis; in some cases (deep mass, mediastinal mass, unacceptable surgical risk), a core needle biopsy is advisable.

Standard staging includes physical examination, evaluation of performance status (PS), and assessment of B symptoms (fever>38°C, night sweats, body weight loss >10% during the 6 months before the diagnosis). Laboratory examinations should include complete blood cell counts; assessment of renal and hepatic function; lactate dehydrogenase (LDH); and screening tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B (HB) virus (HBs antigen, anti-HBs and anti-HBc antibodies), and hepatitis C virus.

A complete radiological assessment with a computed tomography (CT) scan and an 18 flourodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) scan, in addition to a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy evaluation, are required for the staging of the disease, based on the Ann Arbor Classification.

Based on the Lugano Classification, PET-CT is now considered the standard imaging examination, both for staging and for response evaluation, because it is more sensitive to detect nodal and extranodal sites compared with CT scan. However, CT scan is often performed and it is useful to show vessel compression or thrombosis, to differentiate abdominal lymphadenopathy from bowel involvement, to delineate radiation sites, and to measure nodal sites. On this basis, both CT scan and PET are recommended at diagnosis, whereas for evaluation of response only PET could be sufficient. In contrast, in the follow-up setting, PET should not be used, because of a high incidence of false-positive results. Furthermore, recent publications suggest that focal bone marrow FDG uptake, even in the absence of diffuse uptake, is highly specific and more sensitive than bone marrow biopsy for detection of DLBCL involvement, with less than 10% of cases of positive biopsy and false-negative PET imaging. On this basis, bone marrow biopsy has been claimed to no longer be necessary for patients with PET scan positive for bone or marrow involvement. However low-volume (<20%) involvement or the presence in marrow of discordant lymphoma, such as low-grade lymphomas, may be missed by PET scan and this could suggest that bone marrow biopsy should be performed in all cases regardless of PET findings.

In patients with high risk of central nervous system (CNS) recurrence, including patients with high-intermediate and high-risk International Prognostic Index (IPI), especially with more than 1 extranodal site or increased LDH level; or with testicular, renal, or adrenal involvements; or cases with MYC gene rearrangements, a cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) examination with flow cytometry and cytology is recommended. Brain nuclear MRI is recommended in patients with clinical signs of CNS involvement.

A cardiac function evaluation may be useful in all patients with a new diagnosis of DLBCL in case they are candidates for an anthracycline-containing regimen; in particular, a cardiac evaluation is mandatory in elderly patients or patients with known cardiac risk factors.

The Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), based on age, comorbidities, and functional abilities of daily living, is an important tool in the elderly, in order to personalize the treatment and discriminate between fit, unfit, and frail patients.

The risk of infertility secondary to chemotherapy and the fertility preservation options should be discussed with women of childbearing potential and men who are sexually active.

Moreover, DLBCLs localized in particular extranodal sites require specific further examinations for a complete staging. In primary CNS lymphoma, besides diagnostic brain MRI, cytologic evaluation and flow cytometry of the CSF are mandatory and slit-lamp examination should be performed to investigate possible ocular involvement; in DLBCL with gastrointestinal or Waldeyer ring involvement, an endoscopic evaluation should be performed in staging and at the moment of response assessment. In primary testicular lymphoma (PTL), orchiectomy is mandatory for the diagnosis, and ultrasonography of the contralateral testis, a brain MRI, and a cytologic and flow cytometric analysis of CSF are mandatory for a complete staging. In primary breast lymphoma, contralateral breast examination should be performed, whereas the role of a complete CNS work-up remains unclear with the exception of patients with bilateral breast involvement, who are at high risk of CNS progression.

Prognostic index

Prognostic indices are important tools for clinicians to predict the outcome of patients affected by DLBCL.

The standard prognostic score for DLBCL is the IPI published in 1993; based on age, stage, LDH level, PS, and number of extranodal sites, patients are stratified into 4 classes of risk at different prognosis: low, low-intermediate, intermediate-high, and high risk. In patients younger than 61 years, the abbreviate age-adjusted IPI (aa-IPI) should be applied. In the elderly, a prognostic index with an age cutoff point of 70 years has been proposed; the elderly IPI.

With the introduction of rituximab in the clinical practice, a revised version has been developed (rituximab-IPI [R-IPI]). Moreover, the IPI has been reevaluated in a series of 1062 patients with DLBCL treated in clinical trials with the combination of immunotherapy with the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab with a chemotherapy regimen of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and prednisone (R-CHOP), showing that the IPI is still valid in the rituximab era.

Recently, using raw clinical data from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) database collected during the rituximab era, a novel prognostic score, NCCN-IPI, was developed, with the goal of improving risk stratification. Compared with the IPI, the NCCN-IPI introduces as negative parameters 2 levels of increased LDH and the involvement of at least 1 of bone marrow, CNS, liver/gastrointestinal, or lung instead of the number of extranodal sites, and it is able to better discriminate the high-risk subgroup. The new NCCN-IPI was also subsequently validated in a cohort of 1660 patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP between 2001 and 2013 at the British Columbia Cancer Agency ( Table 1 ).

| Risk Group | IPI Factors (N) | Patients (%) | 5-y PFS (%) | 5-y OS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard IPI | ||||

| Low | 0, 1 | 28 | 85 | 90 |

| Low-intermediate | 2 | 27 | 66 | 77 |

| Intermediate-high | 3 | 21 | 52 | 62 |

| High | 4, 5 | 24 | 39 | 54 |

| Revised IPI | ||||

| Very good | 0 | 10 | 94 | 94 |

| Good | 1, 2 | 45 | 80 | 79 |

| Poor | 3, 4, 5 | 45 | 53 | 55 |

| NCCN-IPI | ||||

| Low | 0, 1 | 19 | 91 | 96 |

| Low-intermediate | 2, 3 | 42 | 74 | 82 |

| Intermediate-high | 4, 5 | 31 | 51 | 64 |

| High | ≥6 | 8 | 30 | 33 |

This article discusses the state of the art for the treatment of advanced-stage DLBCL.

Young patients with low-risk International Prognostic Index disease

The role of R-CHOP chemoimmunotherapy in young patients with low-risk IPI was investigated in an important trial conducted by the Mabthera International Trial (MInT) Group. In the multicentric phase III MInT, 824 patients with DLBCL, aged 18 to 60 years, with no risk factors or only 1 risk factor (aaIPI, stage II–IV disease, or stage I disease with bulk) were enrolled. They were randomized to receive 6 cycles of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and prednisone (CHOP)–like chemotherapy alone or in association with rituximab. Additional radiotherapy was planned to bulky localization and extranodal sites. Patients assigned to the rituximab chemotherapy arm achieved a significantly better complete response (CR) rate (86% [82%–89%] vs 68% [63%–73%]) in the arm without rituximab, with 3-year event-free survival (EFS) of 79% (95% confidence interval [CI], 75%–83% versus 59% [54%–64%], respectively) and with 3-year overall survival (OS) of 93% (90%–95%) versus 84% (80%–88%), respectively. The MInT also showed that there is no difference between CHOP21 chemotherapy and more intensive CHOP-like regimens (such as CHOEP21 or MACOP-B) in association with rituximab, underlining that rituximab equalizes chemotherapy regimens with different intensity. Moreover, in this study, 2 different prognostic groups were identified within young patients with low IPI risk, with significantly different 3-year EFS: a favorable one, IPI 0, without bulky disease; and a less favorable one, with IPI 1 or bulky mass or both. The recently updated MInT data, at a 6-year follow-up, suggested a central role of radiotherapy on bulky disease in this less favorable group of young patients.

The management of a similar subgroup of patients, with an age-adjusted IPI equal to 1, was investigated in a phase III randomized study by the Gruope d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA), which compared the standard R-CHOP21 regimen with an experimental arm with a dose-dense rituximab plus doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, prednisone (R-ACVBP) scheme. This trial was conducted in 379 patients, aged 18 to 59 years, affected by previously untreated DLBCL, with an age-adjusted IPI equal to 1. At a median follow-up of 3 years, the dose-dense R-ACVBP arm seemed to achieve a significant better 3-year EFS and 3-year OS compared with R-CHOP21 (3-year OS, 92% vs 84%; P = .007), even if it was associated with an increased incidence of mucositis and hematological toxicities. Note that the R-CHOP21 regimen was given without any radiation therapy. Table 2 summarizes the principal results of studies.

| MInT | LNH03-2B | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 R-CHOP21 IPI 1 N 118 | R-ACVBP N 196 | 8 R-CHOP21 N 183 | |

| Age (y) | 50 (19–60) | 47 (18–59) | 48 (19–59) |

| Stage III–IV | 58 (49%) | 115 (59%) | 93 (51%) |

| Increased LDH level | 58 (49%) | 77 (39%) | 89 (49%) |

| Bulky (>10 cm) | 47 (40%) | 38 (19%) | 45 (25%) |

| 3-y PFS (%) | 86 (78–91) | 87 (81–91) | 73 (66–79) |

| 3-y OS (%) | 92 (85–96) | 92 (87–95) | 84 (77–89) |

| Radiotherapy | 58 (49%) | — | — |

In patients with more favorable features, a reduction of a full course of chemoimmunotherapy treatment could be taken into account and a randomized phase III trial of The German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL) is ongoing (the FLYER trial) randomizing 4 R-CHOP versus 6 R-CHOP.

Standard treatment of advanced stage

Based on the result of the GELA trial, R-CHOP21 represents the standard treatment of patients with DLBCL ; the results showed a CR rate of 76%, an 2-year EFS of 66%, and a 2-year OS of 70%. A long-term analysis performed at a follow-up at 10 years showed a 10-year progression-free survival (PFS) of 37% and 10-year OS of 44%, but these data are affected by deaths from other causes. These data were validated and confirmed in a large retrospective population-based analysis of the British Columbia University that showed a dramatic improvement in the outcomes of patients with the introduction of rituximab to chemotherapy CHOP in the clinical practice setting.

Another trial was conducted by DSHNHL in elderly patients (>60 years old), to investigate the role of dose-dense regimens. In this RICOVER60 trial ; 1222 patients were randomized to receive 6 or 8 cycles of R-CHOP14 administered every 2 weeks with or without rituximab plus radiotherapy on bulky mass. The addition of rituximab to the CHOP chemotherapy regimen significantly improved EFS and OS compared with CHOP alone (3-year EFS after 6 courses of R-CHOP + 2 R was 66.5% (95% CI, 60.9%–702.0%) versus 47.2% (41.2%–53.3%) after 6 cycles of CHOP alone and 63.1% (57.4%–68.8%) after 8 courses of R-CHOP versus 53% (47%–59.1%) of 8 cycles of CHOP alone), but no differences were observed with the addition of 2 further courses of chemotherapy.

In the past few years there was a long debate, indirectly comparing the results of R-CHOP21 with the more dose-dense R-CHOP14 regimen. This debate prompted the design of 2 large randomized phase III trials comparing R-CHOP21 with R-CHOP14 in patients with untreated DLBCL. One trial conducted by the GELA group was restricted to elderly patients, and the second was run by the British National Lymphoma Investigation in patients of all ages and IPI risks. The results of both studies, conducted in more than 1000 cases, failed to show a significant benefit for the dose-dense therapy arm ( Table 3 ).

| Cunningham et al, 2011 N 1080Cunningham | Delarue et al, 2009 N 602 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-CHOP14 | R-CHOP21 | R-CHOP14 | R-CHOP21 | ||

| 2-y PFS (%) | 75 | 75 | 3-y EFS (%) | 56 | 60 |

| 2-y OS (%) | 83 | 81 | 3-y OS (%) | 69 | 72 |

Young patients with high-risk International Prognostic Index

Young patients with intermediate-high/high-risk IPI treated with standard chemoimmunotherapy experience a worse prognosis, and at least 40% still relapse. In order to improve the poor prognosis of these patients, the use of dose-dense regimens of chemotherapy has been investigated in several phase II and III trials, but the benefit remains unclear.

Designed to ameliorate the prognosis of young poor-risk patients with DLBCL, a consolidation with high-dose chemotherapy (HDC) followed by autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) was investigated.

In the prerituximab era, the results of several studies with HDC-ASCT remained controversial ; a meta-analysis on several phase III trials conducted by Greb and colleagues failed to show the superiority of high-dose chemotherapy compared with the standard chemotherapy regimen. On this basis, HDC-ASCT was not recommended as standard frontline therapy in high-risk DLBCL.

With the advent of rituximab in clinical practice, some phase II trials were conducted in order to investigate the role of intensification with HDC-ASCT in young patients with poor-prognosis DLCL, with promising results.

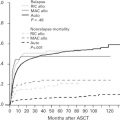

Tarella and colleagues published the results of a phase II study on 112 young patients diagnosed with high-risk DLBCL, with a median age of 48 years (range, 18–65 years), treated with a rituximab-based chemotherapy followed by HDC-ASCT, showing a 4-year PFS of 73% and 4-year OS of 76%.

Vitolo and colleagues conducted a phase II study on 97 patients with analogous unfavorable clinical features; the patients underwent a dose-intensified regimen of chemotherapy with R-Mega-CEOP scheme, followed by HDC-ASCT, obtaining analogous promising results (4-year PFS 73% [95% CI, 63–82] and 4-year OS 76% [95% CI, 68%–85%]).

On these bases, the major cooperative international lymphoma study groups designed phase III randomized trials in order to clarify the role of an intensification with HDC-ASCT compared with standard chemoimmunotherapy in poor-prognosis, patients with untreated DLBCL eligible for transplant.

Le Gouill and colleagues randomized 340 patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL in a prospective multicenter study, comparing R-CHOP14 treatment versus HDC-ASCT; preliminary results showed no differences either in terms of 3-year EFS or 3-year OS.

The Italian phase III trial DLCL04, conducted by the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi (FIL), was designed with a 2 × 2 factorial approach to evaluate the benefit of a full course of rituximab dose–dense chemotherapy at 2 different levels of intensification (R-CHOP14 or R-Mega-CHOP14) compared with a brief program of the same dose-dense chemoimmunotherapy followed by HDC-ASCT (R-HDC-ASCT) in young patients with DLBCL at aa-IPI 2 to 3 at diagnosis. The results of the DLCL04 trial showed a significant improvement in PFS in favor of the intensification with R-HDC plus autologous stem cell transplant, but no differences in terms of OS were observed: CRs were 76% in the R-HDC-ASCT arm versus 72% in the rituximab dose–dense arm, 3-year PFS was 70% (95% CI, 63%–76%) versus 59% (95% CI, 51%–66%) respectively, and 3-year OS was 79% in both arms.

In another randomized phase III trial conducted by the German group, high-risk young patients with DLBCL were randomly assigned at diagnosis to receive R-CHOP14 plus etoposide (R-CHOEP14) and R-MegaCHOEP14. The study showed that the R-MegaCHOEP14 regimen was associated with a significant increase in toxicity, without an improvement of the outcome, compared with conventional R-CHOEP14: 3-year PFS was 61% in R-MegaCHOEP14 versus 70% in R-CHOEP14, and 3-year OS was 77% versus 85%, respectively.

The phase III trial SWOG (Southwest Oncology Group) S9704 conducted by the US/Canadian Intergroup, investigated the benefit of HDC-ASCT in first-line therapy for DLBCL; patients were not randomized up-front but only responding patients after a course of chemoimmunotherapy were randomized. Three-hundred and ninety-seven patients up to age 65 years, with intermediate-high/high-risk IPI DLBCL, stage II to IV, and bulky disease were enrolled to received 5 cycles of chemotherapy CHOP with or without rituximab (with rituximab only in 47% of patients); patients who achieved a complete or partial response (n = 253) were randomized to receive an additional 3 courses of CHOP with or without rituximab (standard arm) or 1 additional course of chemotherapy followed by HDC-ASCT (experimental arm). A significant improvement in PFS was observed in the experimental arm, but this difference did not translate into a benefit for OS. However, an exploratory analysis, conducted only in high-risk IPI patients, suggested an advantage in term of PFS and OS for the intensified arm, with 2-year PFS of 69% in the experimental arm versus 56% in the standard arm ( P = .005) and 2-year OS of 74% versus 71% respectively ( P = .15). Some flaws of this study that may impair the overall results included that only 47% of patients receiving rituximab and many cases with histotypes other than DLBCL, such as T-cell lymphoma, were included in the analysis.

In addition, another Italian phase III randomized study, conducted by Cortelazzo and colleagues, was performed, showing comparable results ( Table 4 ).