Introduction

Faecal incontinence is a common condition which affects up to 21% of community-dwelling elderly individuals over the age of 65 years,1–3 and prevalence in the institutionalized elderly exceeds 50%.4, 5 An acute diarrhoea can result in an incontinence episode even in healthy people, when the rectal reservoir is overwhelmed by liquid/loose stools. Patients with faecal incontinence experience anxiety, fear of embarrassment, emotionally and socially devastating silent suffering, isolation and depression.6 Faecal incontinence, along with urinary incontinence, is among the leading reasons for nursing home placement.7

Anatomy and Physiology of the Anal Canal and Rectum

In order to understand better the clinical presentation, evaluation and treatment options for faecal incontinence, the anatomy and physiology of the anal canal and rectum are briefly reviewed along with changes that occur with ageing.

The rectum is a tubular structure, 12–15 cm in length, with the anal canal extending about 4 cm, from the anal verge to the anorectal ring. The anal canal is separated by a dentate line into an upper mucosal lining and lower cutaneous segment. The area above the dentate line is supplied by the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems, whereas below the dentate line the somatic nervous system provides innervation. Just above the dentate line there are 8–12 rectal columns (anal cushions) with their bases connected to each other. The high-pressure zone of the anal sphincter is formed by the combination of muscles (internal anal, external anal and the puborectalis) and anal cushions.8, 9

The internal anal sphincter is a circular muscle layer that starts from the rectum. The internal anal sphincter is tonically contracted at rest, preventing the involuntary loss of stool and gas.

Tone of the Anal Sphincter

The internal anal sphincter contributes 50–85% of the resting tone of the sphincter with the external anal sphincter contributing 25–30%, the remaining 15% coming from the anal cushions.10–12 In response to rectal distension, the internal anal sphincter tone increases initially, followed by decreased tone constituting the anorectal inhibitory response.8

Changes with Ageing

The thickness of the internal anal sphincter increases with age, as confirmed by ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging.13–15 The functional significance of this change is unclear. It could be a compensatory change for the maintenance of continence,12 but this is unlikely, as the age-related changes in anal sphincter pressures are modest in healthy individuals.16, 17 The most likely explanation is increased connective tissue or ‘sclerosis’ of the internal anal sphincter with ageing.18

The external anal sphincter is a striated muscle surrounding the inner smooth muscle and terminating distal to the internal anal sphincter. Both the puborectalis and the external anal sphincter provide voluntary control of continence in response to various stimuli such as the increased intra-abdominal pressure that occurs with coughing, rectal distension and anal dilatation.9, 19 Voluntary anal sphincter pressure decreases with age and the pressure is lower in women than in men.20

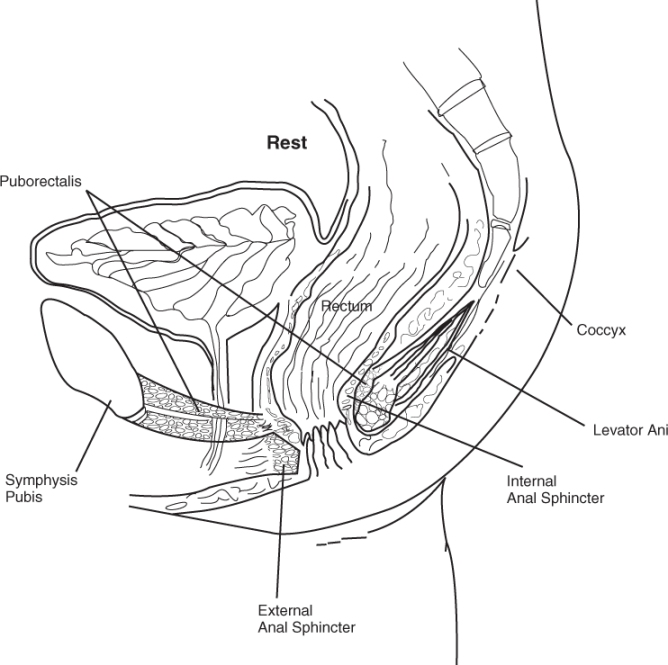

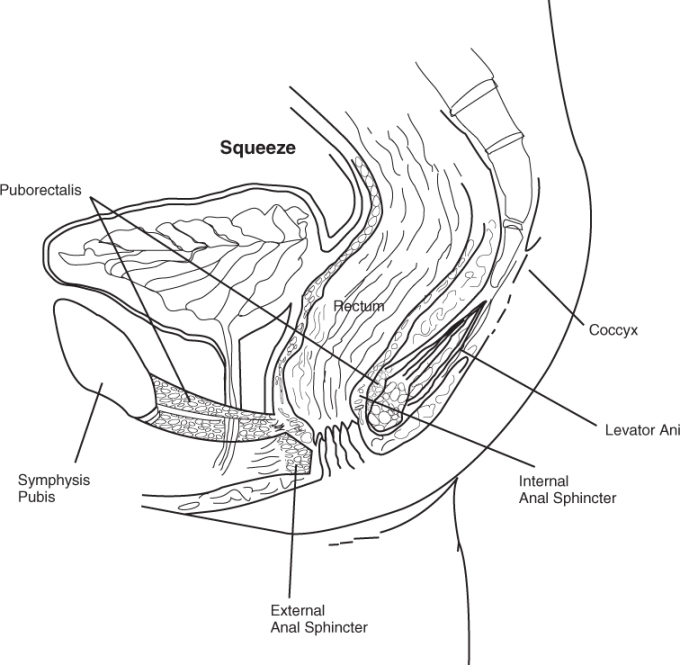

The levator ani muscle is a major component of the pelvic floor and is composed predominantly of three striated muscles: iliococcygeus, pubococcygeous and puborectalis. The puborectalis muscle plays the largest role in continence and is a U-shaped loop of striated muscle slinging around the posterior aspect of the external anal sphincter, pulling the anal canal forwards creating the anorectal angle (Figure 24.1). The puborectalis and resultant anorectal angle aid in the maintenance of continence, as this angle becomes more acute with voluntary sphincter contraction, providing an anatomical obstruction to the distal movement of stool retained above the angle.21

Physiology of Defecation

Both the sensory and motor neurons of the anorectum interact to maintain continence and control the process of defecation. The desire to defecate is usually preceded by propagation of contractions in the proximal colon, resulting in the movement of faeces into the rectum with relaxation of the distal colon/rectum, relaxation of the internal anal sphincter and contraction of the external anal sphincter until the socially appropriate time for defecation.22, 23 The sensory receptors in the anal canal determine the nature of luminal contents, that is, whether the contents are solid, liquid or gas.24 When voluntary defecation is desired, the intra-abdominal pressure rises due to abdominal wall contraction. The muscles of the pelvic floor (external anal sphincter, puborectalis and other muscles of the levator ani) relax. Relaxation of the puborectalis results in straightening of the anorectal angle, providing a straightened conduit for stool movement (Figure 24.2). The anal canal relaxes with the increased rectal pressure, resulting in the evacuation of stool.

Mechanism of Continence

Continence is maintained through the combined action of the external and internal anal sphincters and the puborectalis muscle. Determinants of continence include resting anal tone, resistance to opening at the anus, rectal compliance, normal anorectal sensation and the consistency of stools.25 In addition, mobility and intact cognition are required in order to have a controlled bowel movement. Impairment in any of these mechanisms may result in faecal incontinence.

Prevalence and Importance

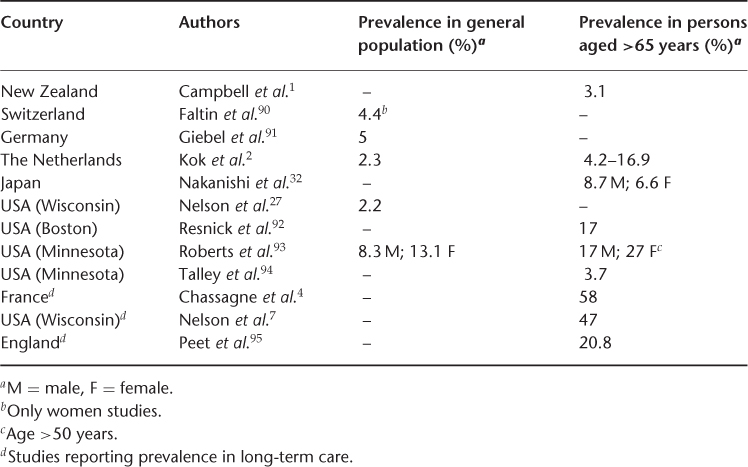

The prevalence of faecal incontinence in the general population is reported to be 2.2%,26 but the study referred to did not include individuals residing in nursing homes. When individuals over the age of 65 years were studied, the frequency of faecal incontinence increased from 3.7 to 27% (Table 24.1). The greatest prevalence of faecal incontinence is found in nursing homes, with more than 50% of long-term care residents affected by chronic faecal incontinence.5 A higher prevalence of faecal incontinence is seen in geriatric hospital wards (20–32%) and geriatric psychiatry patients (up to 56%),28, 29 and 80% of patients hospitalized with dementia also experienced faecal incontinence.10 Double incontinence (i.e. faecal incontinence and urinary incontinence) occurs 12 times more commonly than faecal incontinence alone, with 50–70% of patients with urinary incontinence also suffering from faecal incontinence.28–30 This is not surprising, as the combination of urinary and faecal incontinence is the second most common cause of institutionalization of elderly persons.31

Table 24.1 Prevalence of faecal incontinence.

Faecal incontinence is a marker for poorer overall health and is associated with increased mortality.4, 32 Incontinent nursing home residents experience more urinary tract infections and pressure ulcers.33 The total health care costs attributable to faecal incontinence are difficult to determine as few studies have examined healthcare costs for faecal incontinence alone. Most healthcare cost information comes from nursing homes caring for patients with faecal incontinence, urinary continence or both. The nursing home-related costs for incontinence were $3.26 billion in 1987 and the yearly cost of adult diapers alone is $400 million.34, 35 The additional health expenditure reaches in excess of $9000 per patient-year of incontinence.33

Risk Factors and Causes of Faecal Incontinence

The risks and causes of faecal incontinence are summarized in Table 24.2. Risk factors for faecal incontinence include a prior history of urinary incontinence, the presence of neurological or psychiatric disease, poor mobility, age greater than 70 years and dementia.25, 36 Possibly the most common predisposing condition to faecal incontinence is faecal impaction, which is reported in up to 42% of elderly patients admitted to geriatric units.37 These patients are often chronically constipated resulting in incontinence from leakage around the large faecal impaction. The problem is further complicated by the presence of decreased rectal sensation, allowing the progressive accumulation of stool in the rectum.38 Faecal incontinence in diabetes mellitus occurs from autonomic neuropathy and is exacerbated in the presence of diabetic diarrhoea.39 Pelvic neuropathy may result from prolonged straining and birth trauma. Faecal incontinence results in these patients because of sphincter damage and pudendal neuropathy.40 Trauma to the anal canal such as anal surgery, including haemorrhoidectomy, anal fissure repair and anal dilatation, may disrupt the anal sphincter muscles, resulting in impaired continence.41, 42 Patients with total internal sphincterotomy have a 40% risk of faecal incontinence, while partial sphincterotomy carries a risk of 8–15%.43–45

Table 24.2 Risk factors and causes of faecal incontinence.

| Risk factors23, 27 |

| Prior history of urinary incontinence |

| Presence of neurological disease |

| Presence of psychiatric disease |

| Poor mobility |

| Age >70 years |

| Dementia |

| Causes of faecal incontinence36 |

A. Faecal impaction B. Loss of normal continence mechanism 1. Local neuronal damage (e.g. pudendal nerve) 2. Impaired neurological control 3. Anorectal trauma/sphincter disruption C. Problems overwhelming normal continence mechanism D. Psychological and behavioural problems 1. Severe depression 2. Dementia 3. Cerebrovascular disease E. Neoplasm (rare) |

Clinical Subgroups

There are three main types of faecal incontinence: (a) overflow (b) reservoir and (c) rectosphincteric. Overflow incontinence is specially seen in cognitively impaired, bed-ridden nursing home individuals and the risk factors are outlined in Table 24.3. Reservoir incontinence is seen in individuals with diminished colonic or rectal capacity. This condition is commonly seen with radiation proctopathy, rectal ischaemia, idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease and proctocolectomy with ileoanal anastomosis. Rectosphincteric incontinence is seen in conditions associated with structural damage to one or both anal sphincters, pudendal neuropathy affecting the external anal sphincter and or puborectalis muscle and/or rectal sensation, or degenerative or myogenic disorders affecting the internal or external anal sphincter.

Table 24.3 Risk factors for overflow incontinence.

| Inadequate fibre |

| Inadequate water intake |

| Immobility |

| Inadequate toileting facilities |

| Mental status changes |

| Metabolic abnormalities |

| Hypothyroidism |

| Hypercalcaemia |

| Medication |

| Narcotics |

| Antipsychotics |

| Antidepressants |

| Calcium channel blockers |

| Diuretics |

Evaluation of Faecal Incontinence

The goals in evaluating faecal incontinence include establishing the severity of incontinence, understanding the pathophysiology present and directing the patient to appropriate therapy for their condition. This is accomplished through history, physical examination and investigations targeted at determining the aetiology of faecal incontinence.

History and Physical Examination

The physician may find it difficult to recognize faecal incontinence since patients usually will not volunteer information about incontinence unless asked. This information is best elicited through direct questioning regarding bowel habit and continence. It is helpful to identify when the symptoms first occurred, and to determine if the patient has any sensations such as the passage of stool or gas, fullness in the rectum or warning symptoms such as abdominal cramps and urgency. Inquiry about the home environment may reveal barriers to bathroom facilities, especially in nursing homes and particularly in patients with walkers. Table 24.4 summarizes important areas to address during history. Colitis of any cause may result in loose stools that overwhelm the continence mechanisms. In the evaluation of faecal incontinence, several components of the neurological history deserve attention. A cerebrovascular accident may limit the patient’s physical ability to use the toileting facility. The new onset of faecal incontinence may also herald the presence of cord compression, especially when associated with other neurological symptoms.

Table 24.4 Evaluation of faecal incontinence.

A. History Chronic medical condition Diabetes and chronic diarrhoea or constipation Cerebrovascular accidents or cord compression Dementia and depression Immobility Trauma during childbirth Surgery history Haemorrhoidectomy Haemorrhoidectomy Sphincterotomy Fistulectomy Colon resection and dilatation Radiation to the prostate or cervix for carcinoma Review of medications such as antipsychotic, sorbitol-based medications (theophylline) B. Physical examination Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination or Mini-Mental State Examination Geriatric depression scale Neurological examination Rectal examination |

A thorough review of prescription and over-the-counter medicines and supplements may reveal an underlying cause for the altered bowel habit. Medicines causing diarrhoea include magnesium-containing antacids and poorly absorbed sugars such as sorbitol and mannitol (used in dietetic products). Sorbitol is also frequently used as a base in elixirs, for example, theophylline elixir. The intentional or inadvertent use of cathartics may contribute to diarrhoea and incontinence.

The physical examination helps to identify the pathophysiology of faecal incontinence and can guide the ordering of appropriate tests for further evaluation.46 The usual physical examination may be supplemented by a Mini-Mental Status Examination or Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination, which help identify patients with cognition problems.47, 48 The neurological examination includes assessment of general patient mobility, motor strength and sensory testing. The ‘anal wink’ is elicited by stroking the skin lateral to the anal canal and observing the contraction. Absence of this reflex suggests significant neural damage. Anal gaping can be seen when the buttocks are parted in patients with paraplegia.49 The perineum should be inspected for dermatitis, haemorrhoids, fistula, surgical scars, skin tags, rectal prolapse, soiling and ballooning of the perineum (suggesting weakness of the pelvic floor). Following inspection, the next step is digital rectal examination to note the baseline sphincter tone, squeeze pressure, any asymmetry of the sphincter on squeeze and the amount and character of the stool (hard pellets or soft). The positive predictive value of digital examination is 67% for detecting decreased anal tone when compared with anal manometry.50 Patients with high or normal sphincter tone can also be incontinent, especially in the setting of large rectal volumes or altered rectal sensation. In patients with lesions of the spinal cord or cauda equina, the sphincter tone may be normal, but when pressure is applied to any part of the anorectal ring the phenomena of gaping can be seen. Findings in the normal elderly patient typically reveal lower anal canal pressures.51

Diagnostic Tests

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree