Soft Tissue Sarcoma

RETROPERITONEUM

Anatomy

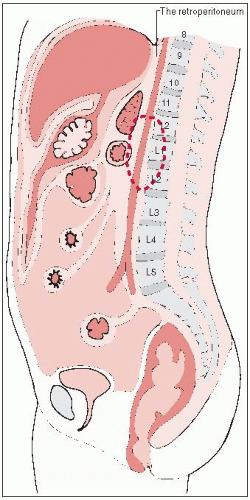

The retroperitoneum is the region of the trunk covered anteriorly by the parietal peritoneum.

Superiorly, it is bounded by the twelfth rib and the diaphragm.

The pelvic diaphragm with the fascia of the levator ani and coccygeus muscles forms the inferior boundary.

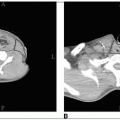

Posteriorly, it is bounded by the fascia of the muscles of the abdominal wall (Fig. 44-1).

Because of the rigidity of the posterior, cephalad, and caudal boundaries, the most common route of expansion and invasion for retroperitoneal tumors is anteriorly into the abdominal cavity.

Natural History

The histology of a retroperitoneal tumor tends to predict the mode of invasion.

Benign soft tissue tumors and well-differentiated sarcomas (myxoid liposarcomas) tend to grow in an expansile manner.

High-grade sarcomas, germ cell neoplasms, and lymphomas often invade and surround the aorta and its main tributaries and the vena cava.

Small round cell tumors (neuroblastoma and rhabdomyosarcoma) can invade into the intervertebral foramina in a dumbbell shape.

Clinical Presentation

Patients present with complaints of abdominal pain or a mass in 60% to 80% of cases.

Fifty percent of patients have weight loss and loss of appetite at diagnosis.

Patients with sarcomas tend not to seek medical treatment until the tumors are large, because these tumors are usually asymptomatic. Patients with a germ cell tumor or lymphoma become more acutely ill.

Several retroperitoneal tumors are associated with paraneoplastic syndromes.

Germ cell tumors can cause precocious puberty in children, and neuroblastoma can produce opsoclonic myoclonus.

Retroperitoneal liposarcoma or lipoma can produce intermittent hypoglycemia.

Extraadrenal retroperitoneal paraganglioma can produce symptoms of excessive catecholamine.

Diagnostic Workup

Evaluation should focus on three factors: physiologic status of the patient, extent of tumor involvement, and histologic characteristics.

In addition to a thorough history and physical examination, a complete blood cell count and blood studies are required to assess the baseline bone marrow, hepatic, and renal status.

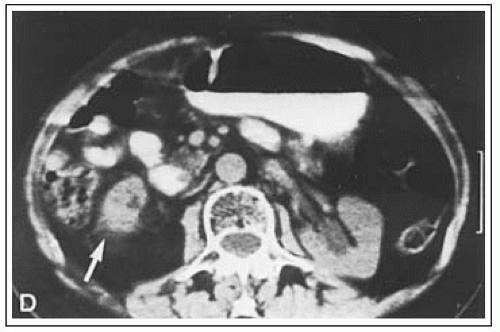

Computed tomography (CT) has changed the detection and staging of retroperitoneal neoplasms because it can delineate tumor size and extent with more than 90% accuracy (18). The ability of CT to predict histology has been more disappointing.

CT has made it possible to obtain histologic and cytologic specimens by needle biopsy, thus enabling diagnosis without a laparotomy (8, 24).

Magnetic resonance imaging can also be used to study retroperitoneal tumors. Chang et al. (2) from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) showed that MR imaging was significantly better than CT at delineating tumor from muscle in sarcomas using T2-weighted spin-echo and inversion-recovery sequences in a study of 20 patients.

TABLE 44-1 Relative Incidence of Retroperitoneal Tumors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Staging System

Staging for retroperitoneal tumors is based on histology.

Pathologic Classification

Retroperitoneal neoplasms are extremely diverse in histopathology because of the embryologic origin of the region in which the mesoderm, urogenital ridge, and neural crest develop (Table 44-1).

Mesenchymal neoplasms predominate in adults. Lipoma and liposarcoma, the most common histopathologic subtypes, constitute 25% to 50% of cases in most studies and can recur, if not excised with a wide margin (7, 10, 12, 19, 20, 23).

The most common retroperitoneal malignancy in children is rhabdomyosarcoma, followed by lymphoma.

The majority of affected infants and children develop germ cell tumors.

Primary germ cell tumors of the retroperitoneum theoretically arise from the embryonic urogenital ridge. Before a definite diagnosis can be made, a thorough examination of the genitalia is necessary. A physical and ultrasonographic examination of the testes are probably adequate in most patients. In six small series, 6 of 18 patients (33%) had a biopsy or autopsy that showed a malignant tumor in the testes (21).

Prognostic Factors

The major prognostic factors are histology, invasiveness, and resectability of retroperitoneal tumors.

General Management

In the past, surgical resection was the only means of achieving a cure in most patients with retroperitoneal tumors (4, 13); this is still true in soft tissue sarcomas.

Nonresectability criteria include involvement of the aorta, vena cava, iliac or superior mesenteric vessels, as well as spinal cord or nerve plexus, peritoneal seeding, and distant metastases (3). Wist et al. (23) showed that 45% of patients survived for 5 years after complete excision, whereas only 8% survived after partial excision or biopsy.

Radiation therapy is usually required in most malignant retroperitoneal tumors because of their infiltrative nature into retroperitoneal soft tissues.

A strong rationale exists for the use of preoperative irradiation to decrease the likelihood of tumor seeding; this facilitates complete tumor resection and minimizes the risk of complications.

Chemotherapy

The role of chemotherapy in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma is well established; vincristine sulfate, doxorubicin, actinomycin D (dactinomycin), and cyclophosphamide are the most commonly used agents.

Germ cell tumors are responsive to etoposide, cisplatin, bleomycin, and vincristine sulfate.

In both germ cell tumor and rhabdomyosarcoma, chemotherapy is often the initial treatment, followed by surgery and irradiation.

Disease-free survival for patients who have complete responses is 75% to 90%, compared with less than 5% in patients who do not completely respond. If disease is present after retroperitoneal dissection, a radiation dose of 40 to 45 Gy can be delivered (9, 11).

In one prospective randomized NCI study, 108 patients were accrued after removal of the primary tumor (16). Among patients assigned to chemotherapy, survival was favorably affected in those with extremity tumors. Patients with head and neck or trunk lesions (including retroperitoneal sarcomas) did not benefit; the 5-year survival rate was approximately 40% in both arms.

Radiation Therapy Techniques

In the treatment of retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcomas with radiation therapy, we prefer preoperative irradiation, with consideration given to an intraoperative or postoperative boost (21). This usually requires that an initial procedure be done (either needle biopsy, if adequate tissue can be obtained, or a small operative procedure) to obtain tissue for histology.

No randomized data prove the value of any specific radiation therapy approach.

Preoperative irradiation is preferred for three reasons: (a) the extent of the local disease is usually easily defined by CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging; (b) radiation therapy morbidity usually is less with preoperative irradiation than with postoperative therapy, since the large primary tumor mass acts to push normal tissues out of the irradiation field; and (c) preoperative irradiation may shrink the tumor, which may allow for a complete resection.

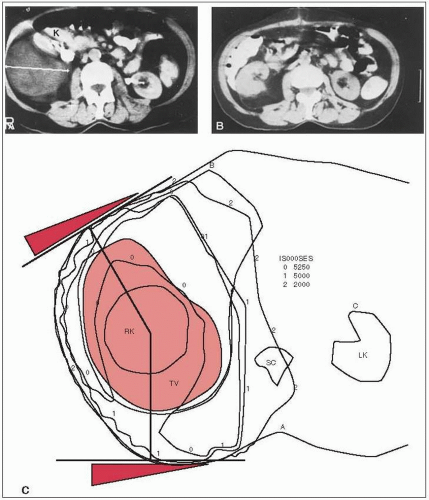

When preoperative irradiation fields are designed, planning based on CT scanning is of great value. Contrast studies of the stomach or small bowel can be useful.

At times, the tumor is well outlined by air-filled bowel seen on a simple radiograph; this can help confirm the location determined by CT scan.

When retroperitoneal tumors are irradiated, careful attention must be paid to the location and radiation tolerance of kidneys, liver, small bowel, and stomach (6).

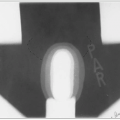

It is common for at least one kidney to be entirely within the irradiation field. In this situation, it is essential that the function of the other kidney be documented with a differential renal scan (Fig. 44-2) and that the total renal function be determined to ensure that there will be adequate residual renal function (5).The contralateral kidney should receive no more than 18 Gy.

The entire liver should not be treated to a dose of more than 30 Gy. If substantial portions of the liver are treated to high doses, one should further decrease the dose to the remainder of the liver to allow for hepatic regeneration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree