Introduction

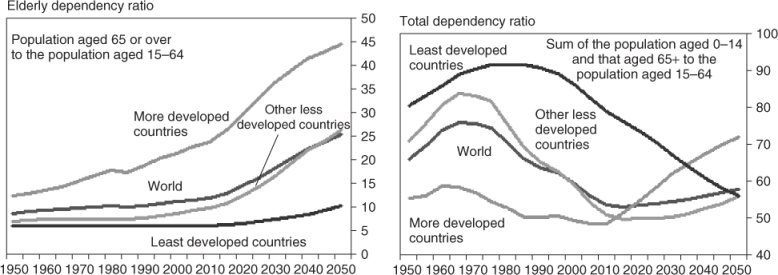

The interactions between social and community factors and access to healthcare are extraordinarily complex (Figure 7.1), especially for the older person. It is important for the healthcare professional to be aware of the impact of these factors on the health and wellbeing of the older person.

Figure 7.1 An illustration of the complex interrelationship between community/social aspects of ageing, the genome and the progression of disease and disability towards death in the older person.

Demography of Ageing

The Greying of Nations

The greying of nations1 is a metaphor that describes the demographic changes that have taken place in all industrially developed countries since the beginning of the twentieth century. It describes an increase in both the numbers of older people and the proportion of the population that is older.

Absolute Ageing

In both developed and developing nations, there has been a rapid growth in the numbers of older people. This has led to a need to ensure that adequate resources are available to meet the growing needs of older persons. Much effort has been placed in designing programmes that would allow older persons to remain in their own homes, ‘to age in place’. These new programmes have included redesigning existing communities to deal with the problems of disability and ageing. The rate at which a nation has aged, its gross domestic product and the political will of the nation to recognize the geriatric imperative are all factors that decide the quality of life for older persons.

The Causes of Absolute Ageing

The increase in numbers of older people is primarily due to their increased survival at younger ages that resulted from improved sanitation and better nutrition, housing and working conditions. More recently, vaccinations of children and older persons, treatment of infectious diseases, improved management of chronic conditions, enhanced neonatal survival and improved care for persons with disabilities have all further increased lifespan.

The number of older persons in a society depends primarily on the number of births 70+ years previously and the subsequent mortality of that cohort over those 70 years.

Relative Ageing

The relationship between the numbers of older and younger people in a society is important. Three factors determine the rate of relative ageing: fertility rates, mortality rates and, at a national level, patterns of migration.

As a country develops economically, there is usually a decline in mortality, which increases the numbers of older people. However, it is not until fertility declines, usually about 20 years later, that the relative age of the population begins to increase. This has happened in all the developed countries, except those whose age structure has been significantly affected by immigration.

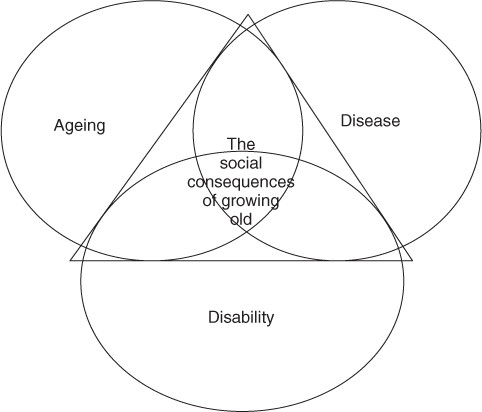

Rising life expectancy and declining birth rate have noticeable effects on the age structure of a population. The old-age dependency ratio is the number of people aged over 65 years per 100 persons of working age (15–64 years old). Between 2005 and 2050, the old-age dependency ratio will almost double in more developed regions and almost triple in less developed regions. The socioeconomic impact resulting from this increasing old-age dependency ratio is an area of growing research and public debate. The old-age dependency ratio is most useful both for those primarily concerned with the management and planning of staff-intensive caring services and for economists and actuaries trying to forecast the financial consequences of pension policies (Figure 7.2). The demographic trend in many less developed countries has a less dramatic effect on the economic systems than in many industrial countries, primarily because less developed countries usually have no or only rudimentary pension systems. However, the societal implication of the demographic development in these countries remains precarious, as a declining number of young people are available to take care of an increasing number of older people.2

Retirement Migration

The distribution of old people, and hence their proportion in the population, varies very much from one part of a country to another. Although the main reasons for this range are variations in mortality and fertility rates, the migration of retirees also affects distribution.

In the USA, the general trend has been a migration from colder to milder climate, especially to Florida, South Carolina, Arizona, Nevada and California. Longino3 described migration patterns of older people in terms of three moves. The first generally occurs at retirement and involves moving for improved amenities (such as weather) and to maintain friendship contacts. The second move is precipitated by moderate functional disabilities, complicated by widowhood, and is often towards the community in which an adult child resides. The third move is due primarily to severe disabilities and is local and towards an institution such as a congregate living or custodial facility (see the section Housing problems).

In England, there has also been a southern migration, particularly to the southern coastal areas. People moved soon after retirement for a variety of reasons (Table 7.1). With the development of the European Union, many persons from the UK now migrate upon retirement to southern Europe. The effect on ageing of these diverse language, cultural and healthcare systems represents a fascinating study for the future. Migration over the lifetime from a poor to a more advantaged community could improve the mortality of the migrants.

Table 7.1 Main reasons for retirement move.

| Bexhill | Clacton | |

| Sample number | 503 | 487 |

| Reasons for moving | ||

| Better climate; cleaner air; sea air | 33 | 19 |

| Health reasons | 11 | 18 |

| Flat country | 1 | 1 |

| To get away from town or live in a quiet place | 16 | 10 |

| To live in a bungalow | 4 | 9 |

| Having to leave a tied house | 5 | 5 |

| The expense of living in the previous place | 5 | 9 |

| To have a change | 7 | 9 |

| To join friends or relations | 10 | 15 |

| Other | 7 | 6 |

Reproduced from Karn,4 by permission of Taylor & Francis.

Although migration for functional elderly to better climates is on the whole positive, the development of disability often leads to frustration. With ageing and the onset of cognitive and other problems, older persons often require advocates to help them make healthcare decisions and to deal with financial problems. The loss of the ability to drive safely dictates that choosing a place to migrate to must take into account the availability of transportation and the juxtaposition of essential shopping and entertainment facilities. In the USA, case managers often assist adult children who live at a distance to provide care for their older parents who wish to remain in their homes (‘to age in place’). The Community Care and Health (Scotland) Act 2002 stimulated changes in community planning for the care of older persons, including personal attendants and free nursing home care.

Effects of Immigration

Two forms of immigration can affect the older person: (1) migration as an adult and (2) migration beyond pensionable age. Adult immigrants may have different rates of certain diseases in older age than the population to which they immigrated, for example, immigrants from Yugoslavia and Hungary had a higher stroke incidence than Swedes living in Malmo, Sweden.5 Alternatively, immigration can lead to altered disease patterns. Japanese immigrants to Brazil have different cancer mortality rates than do Japanese in Japan.6 Immigrants may or may not adapt to the diet and health practices of their host country. Older Koreans in the USA often continue to utilize traditional Korean medicine (Hanbang). Quality of life may also change. Polish-American ethnic elderly had a significantly better subjective quality of life than Polish-immigrant elderly, who in turn had a better subjective quality of life than Poles in Poland.7 Studies of Chinese immigrants to Canada and New Zealand have suggested a high rate of depression in older Chinese immigrants compared with the general population and a similar high rate of depression is seen in Hispanic immigrants.8

In the USA, by 2003, 11.7% of the population consisted of immigrants. These immigrants were more likely to be poor and, as a group, earned less, had less health insurance and obtained less health promotion testing. Despite this, they live 3–4 years longer based on birth and 1.5 years longer at 65 years.9

Immigration has assorted effects on ageing. These may be either beneficial or deleterious. Awareness of health attitudes and health problems specific to older immigrant populations is an essential part of the therapeutic armamentarium of healthcare professionals.

The Male-to-Female Ratio

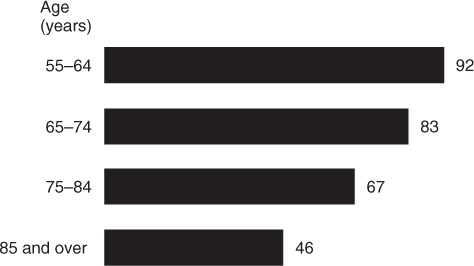

The gender ratio of number of men to 100 women in the older age-groups is an aspect of population ageing meriting special mention. The expectation of life at birth (Table 7.2) is about 5 years greater for females in most developed countries than it is for males. In the UK, the difference between the life expectancy at the age of 60 years is about 3.5 years. In the USA, the gender ratio declines by 67% from ages 65–69 to 100+ years (Figure 7.3).

Table 7.2 Expectancy of life in males and females from birth (years) (2009).

| Country | Males | Females |

| Australia | 79.2 | 84.1 |

| Bangladesh | 57.6 | 63.0 |

| Canada | 78.7 | 83.9 |

| France | 77.8 | 84.3 |

| Germany | 76.3 | 82.4 |

| Israel | 78.6 | 83.0 |

| India | 67.4 | 72.6 |

| Japan | 75.8 | 85.6 |

| Macau | 81.4 | 87.5 |

| The Netherlands | 76.8 | 82.1 |

| Niger | 57.8 | 56.0 |

| Russia | 59.3 | 73.1 |

| Singapore | 79.4 | 84.8 |

| Swaziland | 31.6 | 32.2 |

| South Africa | 49.8 | 48.1 |

| UK | 76.5 | 81.6 |

| USA | 75.6 | 80.0 |

| Zimbabwe | 40.1 | 42.6 |

From Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_life_expectancy) citing CIA figures of countries by life expectancy.

Figure 7.3 Gender ratio of people 55 years and over by age, 2002 (number of men per 100 women). Source: US Bureau of the Census, Annual Demographic Supplement to the March 2002 Current Population Surveys.

There are biological and social reasons for the differences in life expectancy and also for the fact that there are more older women than older men. Biologically, the high mortality of male fetuses and infants and the inhibitory effect of estrogens on the development of atherosclerosis both play a part. However, social influences appear to be more important. In the early twentieth century, there were more men than women among the elderly so this gender ratio is a relatively recent phenomenon. The change would seem to have been due to the differing lifestyles of men and women. The prevalence of cigarette smoking, high alcohol consumption and exposure to hazards of the workplace have penalized men in comparison with women. In some African nations, such as Niger, South Africa and Zimbabwe, the ratio of older males to females is <1.

A higher death rate of men than women during Wars has also affected the ratio, while higher rates of mortality from homicide and road traffic accidents continue to have an effect during peacetime. This is particularly evident in modern Russia, where there is nearly a 12 year difference between males and females related to societal problems, following the fall of the Soviet Empire. Finally, decreased death rates during pregnancy and decreased number of pregnancies have dramatically decreased female mortality (Table 7.3).

Table 7.3 Estimated average number of children to parents born in different years.

| Year of birth of parent | Average number of children | Average number of children surviving to age 45 years |

| 1871 | 4.8 | 2.7 |

| 1881 | 4.1 | 2.5 |

| 1891 | 3.3 | 2.2 |

| 1901 | 2.6 | 2.0 |

| 1911 | 2.2 | 1.7 |

| 1921 | 2.0 | 1.6 |

Reprinted from Exton-Smith and Grimley Evans.10 Copyright 1977, with permission from Elsevier.

As the lifestyles of men and women become more alike, the gap will probably narrow; changes in female morbidity and mortality associated with increased consumption of alcohol and cigarettes are trends already apparent in younger cohorts.

The Changing Family

The structure of the modern family in the post-industrialization period has been influenced by increased age at marriage, increased divorce rate (50% in the USA), high geographic mobility, an increasing proportion of women in the labour force and fewer children. In Europe, Asia, North America and Australia, these trends have been exacerbated in the ‘baby boomer’ generation (those born between 1946 and 1964).

These trends make it difficult for families to look after their elderly relatives when they become dependent. This has created the ‘sandwich generation’, where the middle-aged person needs to provide care for both dependent children and parents. Nevertheless, there is no evidence that the modern family in the UK or USA cares less for its elders than did the family in the past. In fact, in the USA ∼80% of older persons have living children, two-thirds of whom live within 30 min of the elderly parent. Furthermore, ∼75% of those over 65 years of age have some contact (personal or by telephone) each day. Support from adult children (transportation, financial and emotional) makes it possible for 95% of people aged over 65 years to live in the community.11 Most (82%) live independently. Of those who need assistance for functional disabilities, 30% of the needs are met by family members, with the balance being met by a combination of family and formal community agency services.

Only 4.5% of older persons in the USA live in nursing homes, belying myths that families do not provide at least as much support as they did in the past.

Growing Older—The Social Process

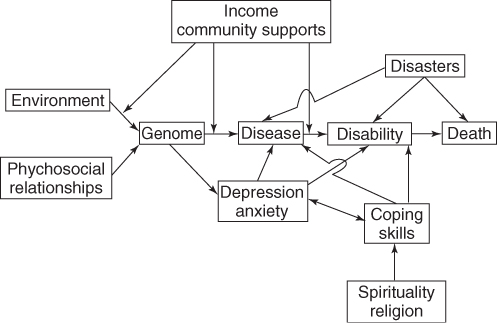

Although the distinction is arbitrary, it is useful to try to separate the effects of physical processes affecting people as they grow older from the effects of the social consequences of attaining an advanced chronological age. There are three of these physical processes—ageing, disease and disability—and these overlap with each other and with the social process which is often called growing old (Figure 7.4).

In this chapter, we will consider the social problems that occur as a result of growing old.

A Life Course Perspective on Age

It is useful to view older people as a product of life course events. Thus, infancy, childhood and adolescence occur in the first two decades of life and involve preparation for a job while living at home as a dependent. Adulthood and middle age bring with them increasing involvement in work, marriage and creating a family in an independent setting. Persons in old age, however, will have experienced departure of grown children, retirement, perhaps death of a spouse, family and friends and increasing dependency, especially from functional health limitations.

From a social psychological perspective, the transition from youth to adulthood may be seen as increasing attachment to one’s social groups through meaningful and productive roles. Likewise, the transition from adulthood to old age may be seen as detachment from one’s social groups as these meaningful and productive roles are given up. This may help account for the reports that the very old are, or at least perceive themselves to be, isolated, a ‘burden to society’ and to have feelings of unworthiness. In fact, clinical depression is a common problem for older people, which could be exacerbated by these perceptions.

Social Problems

When people talk about the social problems of older persons, they are usually referring to certain practical problems that occur more frequently among older people, principally poverty, housing problems, difficulties with transportation and isolation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree