Introduction

Smart homes have been in existence for many years, primarily pursued by those with a love of high-tech living environments. However, despite their rather pretentious label, this technology can provide many benefits to support elderly people and there is a growing body of experience which demonstrates its potential. This chapter looks at the ways in which smart homes can provide support based on the experiences of a number of groups. It considers the issues that have to be addressed if it is to be successful, together with some of the growing evidence for its effectiveness and it concludes with a look at the future of this work.

What is a Smart Home?

The term ‘smart home’ has been confused by some by using it to describe technology that relies on sensors in the home that can send messages to call centres. Such technology is really telecare and will be referred to as such in this chapter. The primary property that endows a house with the smart home label is its ability to support the user in an autonomous fashion. In other words, it can monitor the user’s activities and the way they interact with appliances in the home, but it is also able to supply a response itself to support the user. For example, if a smart home detects a running bath being nearly full it will respond by turning off the taps rather than calling for someone to come and intervene.

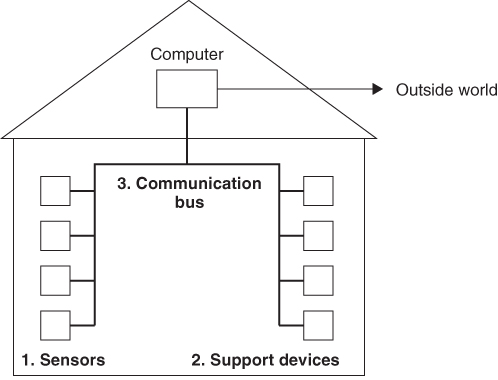

What needs to be incorporated in a house to enable it to qualify for this lofty label? A smart home requires three facilities to be installed in order to operate (see Figure 124.1). First, it requires sensors that can monitor the occupant’s behaviour and activities as described above, for example, by sensing the water level in a bath. Second, it requires a series of support devices so that it can autonomously provide the backup needed to support the user, for example, means for automatically turning off the bath water. Third, the particular feature that distinguishes a smart home, it requires a means whereby all the sensors and the support devices can talk to each other. This facility is achieved through the use of a communication bus, which is conventionally a form of wiring that enables messages to be sent between the sensors and the support devices, although increasingly it is embodied in a wireless form. The communication bus is linked to a computer or other logic controller that can see all the information being provided by the sensors and which can then make judgements about the user’s behaviour. If it decides some action is needed, then it can initiate the activities of the relevant support device.

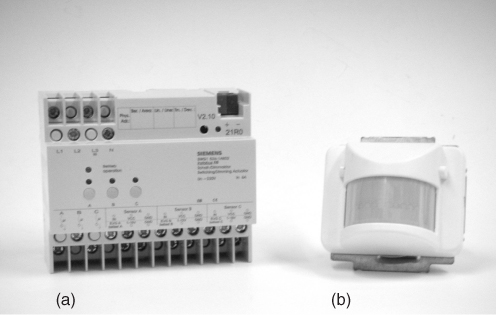

Hence there is nothing particularly complicated about smart technology. It has been around for a long time in installations in larger public buildings such as airports and hotels. In such buildings, the technology primarily enables environmental control to be provided autonomously so that the building is able to ensure that appropriate temperatures, ventilation and so on are maintained automatically. The communication bus, a key feature of such installations, has been the subject of some standardization so that different manufacturers’ components can talk to each other. Many of the components developed for these purposes, such as lighting controls, can be directly applied to usage in domestic homes (Figure 124.2).

Figure 124.2 Standard commercially available smart home components: (a) a light fader unit and (b) a passive infrared sensor.

Applicability to Elderly People

Given the ready availability of smart home components, a number of groups have explored the possibility of using them in a domestic setting to provide support that augments the help received from carers. A lot of work has been carried out to see if people with physical disabilities can be supported. The Edinvar Housing Association in Edinburgh undertook pioneering work to explore the potential of this technology. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) has provided a number of installations in York with a fair amount of success. The JRF has published a number of guides about the technology.1, 2 Some pioneering work in Norway has also explored the potential of this technology to support people with dementia.3 The installations have primarily used commercial smart home components developed for public buildings and configured them in a form that allows their use in a domestic environment. More recently, purpose-designed technology has been developed, such as work at Brunel University on the Millennium Homes project,4 which enabled the home to give voice prompts to the user to check if they needed outside support.

The majority of these installations have used the ready availability of smart home components to provide the technology that is used. For lighting and ventilation, these components are very appropriate. However, there are a number of situations where such technology is not so appropriate and where support devices need to be better tailored to the needs of the end user. A typical example is the use of commercially available technology to provide tap control. Several installations have used taps controlled by an infrared sensor that could be very useful for someone with poor hand function. All the user has to do is wave their hands in front of the sensor, usually mounted just underneath the tap, and water will be provided while the hands are in position. However, this operation is somewhat unnatural and for someone with a cognitive problem such taps would be totally confusing. These kinds of installations take a somewhat technology-led approach to their design. In other words, the installations start from looking at what technology is available and then configuring it in a form that seems to be close to providing the support needed.

The work carried out at the Bath Institute of Medical Engineering on the Gloucester smart house project explores these issues from a somewhat different perspective.5 This project is aimed specifically at supporting people with dementia and uses a design technique that is very user-led. In other words, user needs are explored initially to provide a definition of the kind of problems that have to be supported by the technology. Having made these definitions, the design work then moves on to create purpose-designed devices that provide the care needed.

Ensuring User Friendliness

There is, of course, a spectrum of reaction to technology on the part of elderly people in the same way as there is for any other age group, and some elderly people are very excited and very proficient in using equipment such as computers. However, there is no doubt that interaction with sophisticated technology can cause a lot of anxiety, which may deter many people from using it. Consequently, when it comes to providing supportive technology for the majority of users, it is preferable that the cognitive load on the user is kept as low as possible. The technology should really provide support with as little intervention as possible from the user.

The problems of designing user-friendly installations are exacerbated when it comes to providing support for people with dementia. For such a user group, having to learn new skills or make sense of a new piece of technology is out of the question. The technology really does have to be invisible and just intervene and provide support when the house deems it to be necessary. The technology has to be totally in the background, where the home appears to be just the same as any other home, where the user does not have to learn any new skills or interact with the new technology. But such installations are also going to be very user friendly for more cognitively able users and will be suitable for those who are less able to cope with new technology. Design approaches that embody this approach have been published.6, 7

The individual nature of the problems faced by older people has a big impact on the installation of smart home systems. As with all assistive technology, any means of tailoring it to the needs of the individual will make it more effective. Smart home technology is inherently flexible in that the way in which a system responds depends on the control software and this in turn can be easily configured for the individual. Ideally, installations need to be set up for an individual client by a non-technical professional such as an occupational therapist (OT), and this in turn means that such configuring interfaces also need to be user friendly.

Some Examples of Usage

A few examples can illustrate how new technology can be supportive of someone but require little or no learning. A situation that causes a lot of concern is the problem of an elderly person getting out of bed at night and finding the toilet. For someone who may be unsteady on their feet, rising from lying down to standing is particularly dangerous. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that they are probably in a dark environment. How can smart home technology assist in this situation? First, the house can know whether it is dark or not through ambient light sensors. It can also detect whether someone is in bed and about to get up by means of bed-occupancy sensors. These can be placed underneath the bed legs or across the mattress to detect a weight change (see Figure 124.3). Sometimes pressure-sensitive mats are used on the floor next to the bed, although experience has shown that some users will make a point of not treading on the mat once they have learnt that it is there. Given this information, the house can ensure that when someone gets out of bed in the dark the bedroom light or a bedside lamp is turned on. To reduce the possibility of alarming the user, the light can be activated through faders so that they fade up to a fairly low level in a gentle manner (Figure 124.4). In this way, the user is provided with lighting to help them orientate more easily and move around without tripping or bumping into things. The process can also be reversed. If the user gets back into bed but forgets to turn off the light, the house can again detect that this has happened and can turn the lights off automatically.

This simple use of smart home technology can be taken further. The movements of an occupant about a room can be easily and reliably detected using passive infrared sensors (PIRs). These are the kind of sensors that are used in most home security systems and burglar alarms. It is easy to arrange for lights to come on automatically as the user moves around the house, again ensuring that they have illumination and help reduce falls. If the user has got out of bed and begins to go out of the bedroom, the house could make an initial assumption that they probably want to go to the toilet. It could then fade up the toilet lights and fade down the bedroom lights. In this way, it provides guidance to the toilet for the user. When the user has finished in the toilet and begins to go out of the bathroom, the house could reverse its response, fading up the bedroom light again and fading down the toilet one. In this way, the house can provide guidance to the user moving around the house in addition to providing illumination.

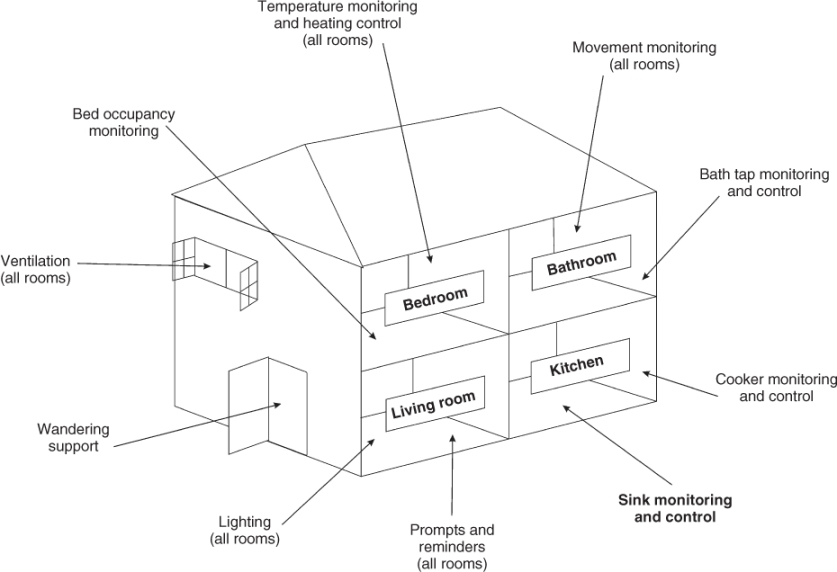

There are many other ways that smart house technology can provide support to the occupant (see Figure 124.5). For example, the house can detect if something slightly dangerous has been done, say in the kitchen, and then provide prompts and support. In a similar way, the use of other domestic appliances such as the bath and the kitchen sink can be backed up by keeping water temperatures safe and turning off taps as described above. For people with dementia, the house can keep an eye on wandering tendencies and try to discourage going out of the house and calling for help if it occurs. The house can also provide prompts for activities that need to be carried out such as taking medication or provide a form of day diary to remind people of visitors or mealtimes or even a favourite TV programme. In many ways, the house acts like an extra carer, but one that acts for 24 h per day without becoming tired or frustrated. However, of course it can never supply the qualities of personal human care and it is crucial that installers bear this in mind and do not just see smart homes as a cheap replacement for normal caring.

Appropriate Design

Simple application of smart home technology can, in the ways illustrated, provide a lot of support for the user. However, if it is to be effective it has to be designed from a close understanding of the issues that are likely to arise and the way in which users are likely to interact with the technology. A very useful rule of thumb that was used in the development of technology within the Gloucester smart house project was to try to design new support equipment that reacted in a way that emulated the behaviour of personal carers. The reasoning behind this approach was that in many circumstances a personal carer is likely to be the person who best understands what works in caring for the person they are looking after. If they have developed a strategy that works for them, it is likely that any new technology that reacts in a similar way is going to be helpful. Surveys of personal carers showed that there was often a good consensus about strategies found to work. This understanding was a starting point for the new technology developed by the team for use in a smart home. During the design and development work, whenever a situation arose where it was not clear how the technology should react, it was found to be very useful to ask, ‘What would the carer do in this situation?’. In this way, the technology is being designed to act as a kind of invisible carer that is ever present, just looking over the user’s shoulder, checking that things are alright and just providing help when needed.

A good example of the use of the ‘carer emulation’ approach is provided by the designs used to control a bath. It would be easy to install a bath water-level sensor that shuts off the water supply when the bath is nearly full. Such a facility would ensure that a forgetful user did not flood the bathroom. However, if they came back to add some more hot water or they let out the water and wanted to run a bath the next day, they would find that the taps did not work because the water had been shut off. A key element in maintaining quality of life for someone with a cognitive problem is to enable them to feel they are still in control of their lives, and finding that their house is taking that control away from them would be counterproductive. How would a carer react to the problem of someone forgetting they were running a bath? It was found that, in these kinds of situations, the carer would follow a simple three-stage response. They would first provide a reminder, ‘Don’t forget you’ve got the bath running’. If that did not do the trick, they would then intervene to turn off the bath (or the cooker or other appliance). However, they would turn off the tap in the usual way, which would mean that it could still be used subsequently. Third, they would provide some reassurance to the user, such as, ‘I’ve turned off your bath. It’s ready now’, so that the user knew why something had happened.

All these actions can be emulated by the smart home, but there is a need for some additional technology. There is a need for a means of communicating with the user, to provide prompts and reminders, and this was done through the use of voice recordings. There is also a need for a means of turning off the bath taps in such a way that the user can still carry on using it themselves (Figure 124.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree