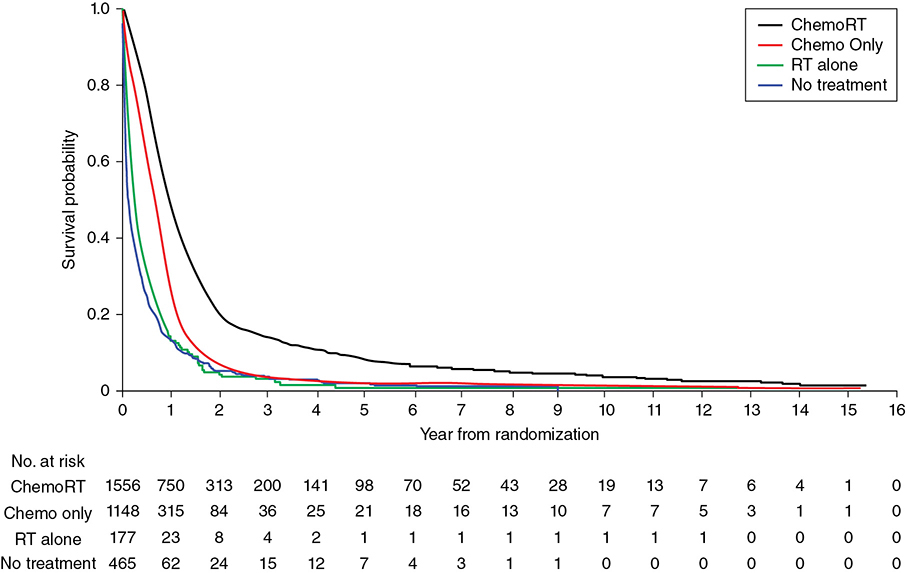

A 62-year-old Caucasian male with an 80 pack-year smoking history, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and diabetes presents with progressively worsening shortness of breath over the past week. He is saturating 86% on room air in the emergency room, requiring oxygen at 5 L per nasal cannula and eventually bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP). Examination of the arterial blood gas (ABG) shows he is hypoxic and hypercapnic. His breathing becomes more labored, and he is electively intubated. Chest computed tomography (CT) shows bilateral pulmonary nodules with bulky mediastinal and hilar adenopathy. Abdominal/pelvic CT shows multiple hepatic lesions. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is negative for brain metastases. Biopsy of a liver lesion returns with presence of small cell carcinoma. Learning Objectives: 1. When should you expect to see a response in small cell lung cancer (SCLC)? 2. What is a common chemotherapy regimen for SCLC? 3. What is the recommended first line treatment for extensive stage SCLC? As with early stage SCLC, metastatic SCLC also has a dramatic response initially, with response rates of 60%-70% with chemotherapy alone. However, even with appropriate treatment, the median survival rates are only 9-11 months, and the 2-year survival rate is less than 5% in these patients.1 Small cell lung cancer is very sensitive to chemotherapy and often has a dramatic response within 1-2 cycles. Many chemotherapy combinations have been evaluated for extensive stage SCLC, but none has had consistent benefit when compared to cisplatin/etoposide. A Japanese phase 3 trial showed promising results, with 154 patients randomized to either cisplatin/irinotecan or cisplatin/etoposide.2 Those treated with cisplatin and irinotecan had a significantly better overall response rate (84.4% vs. 67.5%), median survival (12.8 months vs. 9.4 months), and 1-year survival (58.4% vs. 37.7%) compared to those treated with cisplatin and etoposide, respectively. The irinotecan arm had more grade 3 and 4 diarrhea, while the etoposide arm had higher rates of myelosuppression. The Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) tried replicating the trial using the same schema but failed to show a significant difference in response rate or overall survival.3 However, another phase 3 trial involving 220 patients did find that median overall survival was slightly improved (8.5 months vs. 7.1 months, p = .04) with carboplatin/irinotecan compared to carboplatin/oral etoposide.4 A meta-analysis went on to suggest improved progression-free survival and overall survival with irinotecan plus a platinum drug when compared to etoposide with a platinum drug, but this meta-analysis did not use individual data, and the small absolute survival benefit needed to be balanced with toxicities from irinotecan.5 Based on these findings, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines consider carboplatin and irinotecan as an option for extensive-stage SCLC but continue to recommend etoposide plus platinum regimens. Many studies have evaluated whether adding a third agent to the current cisplatin/etoposide regimen would improve treatment for extensive-stage SCLC. Two trials added ifosfamide or cyclophosphamide plus an anthracycline to cisplatin/etoposide but only found a modest survival advantage at the cost of significantly increased hematologic toxicities.6 Adding paclitaxel to a platinum regimen with etoposide had promising results in phase 2 trials but failed to improve survival in phase 3 studies.7 The Global Analysis of Pemetrexed in SCLC Extensive Stage (GALES) aimed to show non-inferiority of pemetrexed plus carboplatin compared to carboplatin plus etoposide, but the study was terminated prematurely once the pemetrexed arm was found to actually be inferior.8 The experimental arm had a median progression-free survival of 3.68 months compared to 5.32 months for carboplatin/etoposide and a preliminary overall survival of 7.3 months for pemetrexed/carboplatin compared to 9.6 months for carboplatin/etoposide. Studies have also looked at the role of immunotherapy as both first-line and maintenance therapy in SCLC. One phase 2 study combined ipilimumab after an initial administration of carboplatin/paclitaxel and found improved immune-related progression-free survival, but a phase 3 trial of ipilimumab added to platinum/etoposide failed to show any difference in progression-free survival or overall survival.9 Most recently, the study of carboplatin plus etoposide with or without atezolizumab in participants with untreated extensive-stage (ES) small cell lung cancer (SCLC) (IMpower133) trial met its coprimary endpoints of progression-free survival and overall survival. The phase 4 trial randomized 403 patients to atezolizumab plus carboplatin and etoposide versus carboplatin and etoposide alone. After 4 cycles of treatment, patients10 went on to receive either atezolizumab or placebo as maintenance until disease progression. The median progression-free survival improved with atezolizumab (5.2 months vs. 4.3 months), as did overall survival (12.3 months vs. 10.3 months) and 1-year survival rate (51.7% vs. 38.2%).11 The role of bevacizumab in treatment for metastatic SCLC is unclear. Several phase 2 studies have shown improved response and survival outcomes with bevacizumab added to chemotherapy. One study involved 52 patients treated with irinotecan, carboplatin, and bevacizumab for 6 cycles. Patients with no progression went on to receive maintenance bevacizumab. The response rate, time to progression, and survival outcomes were found to be better than chemotherapy alone.12 Another study of 63 patients involved treatment with bevacizumab plus cisplatin and etoposide followed by bevacizumab alone until disease progression or death. This study found improved progression-free survival and overall survival relative to historical controls who received cisplatin and etoposide with minimal increase in toxicities compared to chemotherapy alone.13 However, these results have not been consistent. One phase 3 study also randomized 204 patients to cisplatin/etoposide with or without bevacizumab. Those in the bevacizumab arm who did not have disease progression after 6 cycles of treatment continued on bevacizumab alone until disease progression. At the median follow-up, the median overall survival times for the chemotherapy-alone arm versus chemotherapy plus bevacizumab were 8.9 months and 9.8 months, and 1-year survival rates were 25% and 37% (hazard ratio 0.78, 95% CI 0.58-1.06, p = .113), respectively. There was a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival but not in overall survival.14 Another study found no difference in response or progression-free survival in patients who received chemotherapy plus bevacizumab versus those who received chemotherapy alone.15 Chemotherapy for SCLC has traditionally been given for 4-6 cycles based on randomized trials, but there is no ideal number for treatment cycles. Many have looked at whether maintenance or consolidation treatments are of any benefit to these patients. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) randomized patients who had not progressed after initial therapy to either consolidation or maintenance with topotecan and found the progression-free survival from the treatment arm was significantly better (3.6 months vs. 2.3 months, p < .001).16 However, overall survival for the topotecan versus observation group was not significant (8.9 months vs. 9.3 months, p = .43). A meta-analysis of 14 trials looking at consolidation or maintenance therapy in these patients found that the 1- and 2-year odds ratios for progression-free survival and overall survival favored prolonged treatment.17 However, these results were not based on individual patient data, and the trials involved not only differed in their designs but also outdated regimens were used by most. As a result, there was still no definitive recommendation for continuing chemotherapy beyond the initial 4 or 6 cycles. There is currently no role for maintenance chemotherapy. However, immunotherapy may be used after initial treatment based on newer data. A phase 2 trial used pembrolizumab as maintenance after 4-6 cycles of platinum/etoposide but ultimately failed to show improvement in progression-free survival or overall survival.18 Currently, only atezolizumab is recommended for maintenance therapy based on significant results from IMPower133 as mentioned previously. Despite being very sensitive to treatment initially, most patients with SCLC eventually relapse with relatively resistant disease. Response to subsequent treatment depends on the time from initial therapy to relapse. If this time is less than 3 months, response to second-line therapy is expected to be poor (<10%). If this time is greater than 3 months, response rates are slightly better at about 25%. Patients with relapse while on atezolizumab maintenance that is more than 6 months from the initial chemotherapy induction can also be treated with the original regimen but without atezolizumab. The exception to this is for patients initially treated with carboplatin/etoposide/atezolizumab who relapse more than 6 months while on atezolizumab maintenance. These patients should receive carboplatin/etoposide without atezolizumab next. For resistant or refractory disease, there is no standard treatment, so when possible, patients should be referred for a clinical trial. For relapse that occurs within 6 months, treat with a second line regimen. Single-agent topotecan is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as second-line therapy for patients who relapse after initial chemotherapy. An older phase 3 trial compared single-agent intravenous topotecan to CAV (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine) and found similar response rates but a better toxicity profile with topotecan.19 Another phase 3 trial compared oral topotecan to best supportive care and found improved overall survival (26 weeks vs. 14 weeks).20 Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab was recently added to guidelines, with preliminary data showing a 1-year survival of 42% with nivolumab/ipilimumab together and 30% in those receiving nivolumab alone.21 Immunotherapy in SCLC is discussed further elsewhere in this book. There is no optimal duration of subsequent systemic therapy, and it should usually be continued until 2 cycles beyond the best response, progression of disease, or unacceptable toxicities. Second-line options for extensive stage SCLC are as follows: • Subsequent therapy options The incidence of lung cancer increases with age, but elderly patients are unfortunately underrepresented in clinic trials. Though being older does portend more adverse reactions with treatment, age alone should not be a factor in deciding treatment options. Randomized clinical trials have shown that single-agent chemotherapy is inferior to combination chemotherapy in the elderly patients with good performance status though toxicities including fatigue and myelosuppression were more common. For elderly patients with SCLC, using a smaller area under the curve to dose carboplatin takes into consideration the declining renal function in these patients.22 Overall, elderly patients appear to have a similar prognosis as younger, stage-matched patients. Poor performance status is a universal indicator of poor tolerance to treatment. These patients tend to have more toxicities with treatment and are ineligible for clinical trials. However, given the sensitivity of SCLC to chemotherapy, some patients may have an improvement in their performance status once treated. A retrospective review of 7 trials found that 21% of 152 patients who initially had a performance status of 2 converted to that of 0 or 1 after salvage therapy with topotecan.23 A Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) meta-analysis found that tolerance to therapy was more dependent on dose intensity than performance status.24 One study randomized patients with poor performance status to either a 4-drug regimen of ECMV (etoposide, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and vincristine) or EV (etoposide, vincristine). The two groups had similar response rates, palliation of symptoms, and survival, but not surprisingly, the 4-drug arm had greater toxicities.25 Oral etoposide was once thought to be more suitable for patients with poor performance status until a study randomized patients with performance status of 2-4 to either oral etoposide or standard chemotherapy with cisplatin/etoposide or CAV.26 Palliation of symptoms was similar for both groups, but survival was lower in the oral etoposide arm (130 days vs. 183 days). Another trial similarly compared oral etoposide versus CAV or cisplatin/etoposide in patients who were either younger than 75 years old but with poor performance status of 2-3 or older than 75 years with any performance status. The oral etoposide arm again had a lower median survival (4.8 months vs. 5.9 months) and a 1-year survival rate (9.8% vs. 19.3%).27 Though a poor performance status typically predicts a patient’s inability to tolerate treatment, it may be the result of the disease itself in SCLC patients, so treating the underlying malignancy may improve their functional status. Small cell lung cancer is associated with paraneoplastic syndromes, the most common of which is syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), which is marked by hyponatremia, euvolemia, and confusion. Immediate treatment includes fluid restriction, demeclocyline, vasopressin receptor inhibitors, or hypertonic saline. As with all treatments for hyponatremia, sodium should be corrected slowly to avoid central pontine myelinolysis. Another commonly mentioned paraneoplastic syndrome in SCLC is Lambert-Eaton, in which antibodies attack voltage-gated calcium channels, resulting in proximal leg weakness. Small cell lung cancer can also produce anti-Hu (ANNA-1) antibodies that cross-react with small cell carcinoma antigens and human neuronal RNA-binding proteins. These patients can develop encephalomyelitis and other severe neurologic deficits.28 In addition to treating the underlying malignancy, corticosteroids, plasmapheresis, and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) have been used. A 60-year-old white female has a central 3-cm lung mass and on positron emission tomography (PET) diffuse osseous metastases. She smoked 2 packs of cigarettes per day and has COPD and coronary artery disease (CAD). The pathology shows SCLC. Her performance status is ECOG 2 due to dyspnea. How will you treat her? Learning Objective: 1. What is the role of consolidation radiation therapy in metastatic SCLC? The use of thoracic radiation in patients with metastatic SCLC continues to evolve. Initial support of integrating consolidative thoracic radiation into the treatment paradigm was based on the results from the work of Jeremic et al. Patients were only included in the study if they had low-bulk metastatic disease. Only after an initial complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) to systemic chemotherapy were patients randomized to receive sequential thoracic radiation using an accelerated fractionation technique versus further chemotherapy. In patients who received thoracic radiation, the mean survival was increased from 11 months to 17 months.29 Additionally, our institutional data combine with information from the Kentucky Cancer Registry demonstrated improvements in overall survival in patients with extensive-stage disease who were treated (Figure 18-1). Figure 18-1. Kaplan-Meyer survival curves for patients with extensive-stage SCLC. The data demonstrate the addition of radiation to chemotherapy (ChemoRT, black) leads to a survival benefit over chemotherapy alone (red) or radiation alone (green). Studies that are more contemporary have attempted to clarify the role of consolidative thoracic radiation in improved survival. The Dutch CREST trial was designed to randomize patients with good performance status and with extensive-stage disease with any response to chemotherapy to either no further treatment or thoracic radiation using 30 Gy in 10 fractions. The primary endpoint of 1-year overall survival was not significant, but secondary analysis of the 2-year survival endpoint showed an overall survival improvement from 3% to 13%. Thoracic progression was also less likely in the group receiving radiation. The authors concluded that patients with a response to systemic chemotherapy should be considered for both prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) and consolidative chest radiation.30,31 In a follow-up report, the authors also stated that the benefit was most pronounced in patients with residual disease after chemotherapy.30 The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG 0937) attempted to further explore the question of consolidative chest radiation.32 The premise of the phase 2 randomized trial was to highly select patients with limited extrathoracic metastasis whom were presumed to have more favorable biology. The term oligometastatic was applied to this group of patients by limiting enrollment to patients with 1-4 extrathoracic metastases. Eligible patients had to have a PR or CR to 4-6 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy at a minimum of 1 site of disease and no evidence of progression at any site. Patients were randomized between PCI alone versus PCI plus consolidative radiation of 45 Gy in 15 fractions to all extracranial disease. Metastases were alone treated if residual disease remained after chemotherapy. The study was closed early because of futility at the interim analysis. The median survival was 15.8 months in the PCI arm and 13.8 months in the PCI plus consolidative radiation. Patients who received extracranial radiation had delayed progression compared to the PCI-only group. Although the RTOG 0937 study failed to confirm a survival advantage as seen in the Jeremic29 and Slotman31 studies, important conclusions may be drawn from the results. In highly selected patients with extensive-stage disease, survival rates may approach that of patients with limited-stage disease.33 The survival advantage compared to historical data evaluated for extensive-stage patients is likely attributable to selection rather than the use of thoracic radiation. Much of this may be from the routine use of PET/CT as part of the staging workup.34 Radiation therapy may also alter the pattern of failure in patients with extensive-stage disease. RTOG 0937 showed that patients were more likely to fail at sites of initial disease, but those patients receiving extracranial radiation were less likely to have locoregional progression at a site of first failure. Although a possible benefit was seen in controlling locoregional disease, the response was not durable.

18

SMALL CELL LUNG CANCER TREATMENT: METASTATIC

CHEMOTHERAPY FOR METASTATIC SMALL CELL LUNG CANCER

CHEMOTHERAPY DOUBLET

CHEMOIMMUNOTHERAPY COMBINATION

BEVACIZUMAB

DURATION AND MAINTENANCE THERAPY

SECOND-LINE THERAPY

Topotecan

Topotecan

Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab

Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab

Pembrolizumab

Pembrolizumab

Irinotecan

Irinotecan

Paclitaxel

Paclitaxel

Docetaxel

Docetaxel

Temozolomide

Temozolomide

Vinorelbine

Vinorelbine

Oral etoposide

Oral etoposide

Gemcitabine

Gemcitabine

CAV

CAV

Bendamustine

Bendamustine

ELDERLY

POOR PERFORMANCE STATUS

PARANEOPLASTIC SYNDROMES

RADIATION THERAPY FOR METASTATIC SMALL CELL LUNG CANCER

THORACIC RADIATION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree