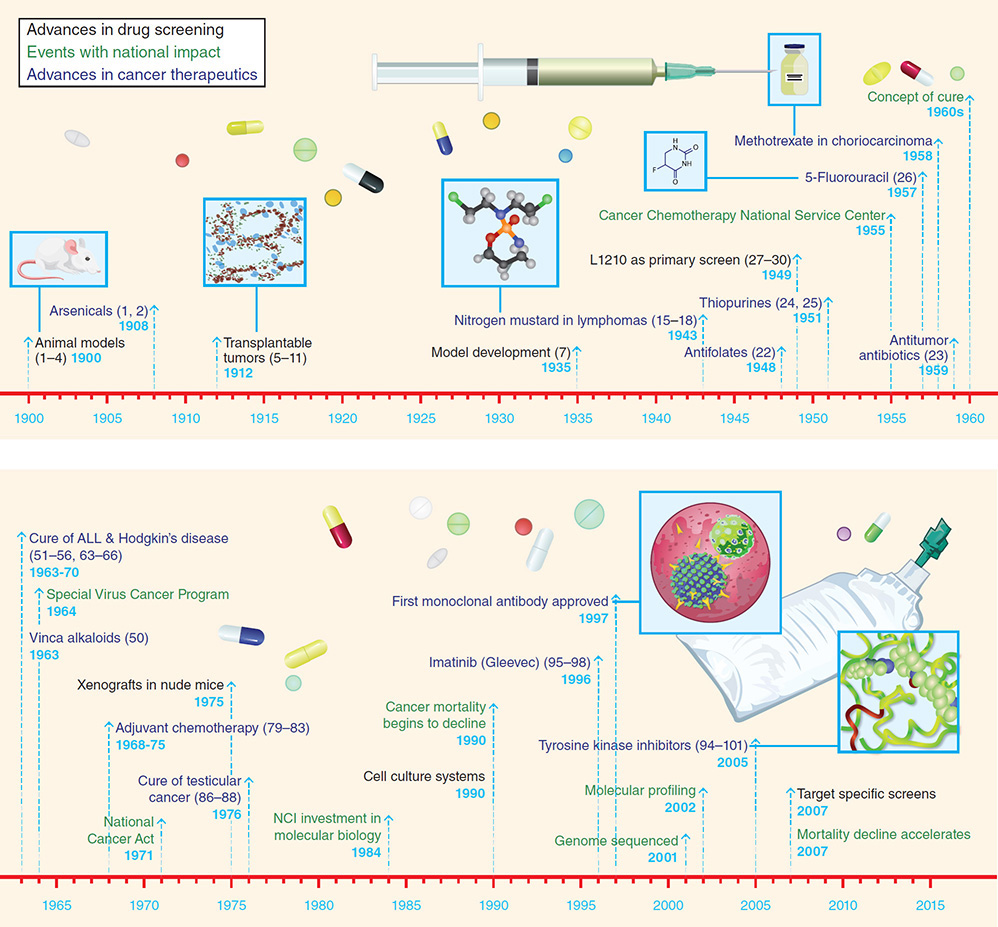

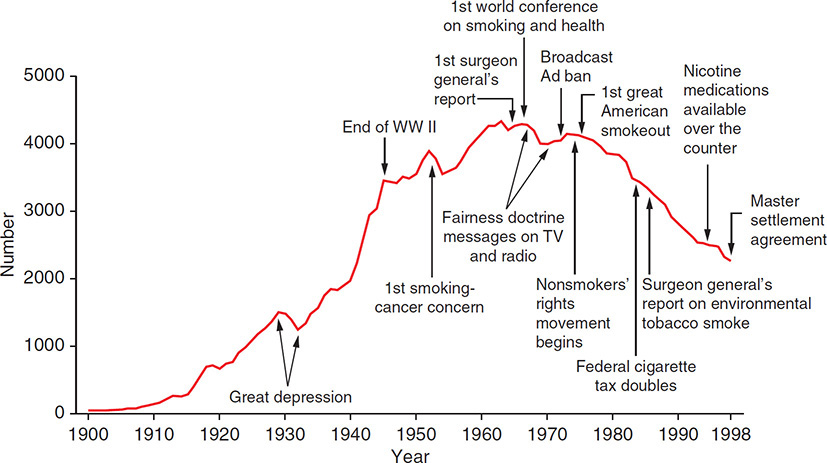

A medical student reading about lung cancer notices that the number of lung cancer deaths has steadily increased worldwide. She asks when lung cancer was first described in the medical literature and how it was treated in the past. She wonders, how the frequency of deaths due to lung cancer compares to the frequency of deaths due to other cancers. Learning Objectives: 1. Who described cancers within the chest for the first time? 2. How was lung cancer diagnosed and treated in the last 200 years? 3. For how long has lung cancer been the most common cause of cancer deaths globally? In 1912, Isaac Adler published the first literature review about lung cancer.1 He listed the known 374 cases mentioned in several European registries over the preceding 50 years. Most physicians at the time thought of lung cancer as an extremely rare disease, and Dr. Adler suspected that lung cancer was underdiagnosed. Not all cases were diagnosed by microscopy, but the number of reported cases had been rising since the mid-1800s.2 The concept of cancers arising in the lung has been a rather recent development in medical history. In the 1800s, Dr. René Laennec at the Hopital Necar in Paris started a new practice of combining postmortem pathology with clinical observation. Dr. Laennec also is known for his invention of the stethoscope. He was a keen clinical observer and well-published writer. The lesions that Dr. Laennec described based on his autopsies were unlike the well-known tuberculosis cases in the 1800s. He described these lesions as encephaloid (cerebral) or medullary tumors due to the visual appearance, which was similar to brain tissue. Dr. Laennec was the first author to describe them as cancers arising from the lung. Dr. Laennec’s work was soon translated into English by John Forbes in 1821 and reached a wider audience, who became aware of this new entity of cancer arising in the chest.3 New medical journals, such as the Lancet Journal (launched in 1823), promoted the practice of autopsies and helped their readers identify lung cancer as a diagnosis apart from the widespread tuberculosis.2 The paradigm of cancer’s cellular origin was slowly evolving in the middle of the 1800s based on microscopic work by Theodor Schwann, Johannes Mueller, and Matthias Schleiden.4 Microscopes, as well as new histological staining and fixing techniques, helped decipher the nature of cell growth. In 1858, Dr. Rudolf Virchow published his book on cellular pathology.5 He lectured on cellular pathology in the 1860s and the new cellular pathology replaced the theory of humoral imbalances which has been the pathological concept explaining diseases since ancient times. The lung cancers in the 19th century were often called fungiform and encephaloid tumors following Laennec’s terminology. The diagnosis was mainly based on history and autopsy and not always on histopathology. The identification and terminology were evolving faster in the case of breast cancer because of the better surgical access to breast cancer than to the interthoracic lung cancer. Since the tumor was not easily accessible and microscopic examination of tissue was not routinely done, it took until the development of chest x-rays and bronchoscopy in the early 20th century to diagnose lung cancer more frequently and reliably. The epidemiology of lung cancer in the 19th century is therefore difficult to assess. Medical statistics was not commonly used. The field started with Pierre Charles Alexandre Louis (concerning debunking bloodletting) in the early 19th century and was further pioneered by John Snow (concerning the cholera epidemic) and Florence Nightingale (concerning sanitation). Cancer, however, was not the main interest of epidemiologists in the 19th century; rather, the focus was on diseases such as gout, congestive heart failure, and tuberculosis. In the late 19th century, cancer was increasingly mentioned in registries.2 A registry in Frankfurt, Germany, listed all cancer deaths in the city, and lung cancer was found to involve less than 1% of the deaths. The surgical resection of lung cancer evolved in the first part of the 20th century. Surgery within the chest was mainly driven by trying to treat tuberculosis. Another reason why thoracic surgery became more standard was the treatment of war casualties, often involving the chest, during the World War I (WWI). It is important to know that surgery in the early 20th century was done in spontaneously breathing patients. At the time, surgery was limited to the collapse of the lungs when opening the chest cavity. To circumvent this problem, Dr. Ernst Ferdinand Sauerbruch developed the negative-pressure chamber, in which the operating field was within a negative-pressure chamber.6 At the same time, Dr. Morristan Davies, a young surgeon in the United Kingdom, started active intubation; however, this was performed without anesthesia. Dr. Davies is also credited for doing the first lobectomy in 1912 on a young man with lung cancer. The patient unfortunately succumbed to postoperative empyema. Dr. Ivan Magill developed artificial ventilation in the 1920s, which made chest surgery more feasible by intubating one lung while doing surgery on the other lung. This technique became standard of care after the 1940s.7 Dr. Evarts Graham accomplished the first curative resection of lung cancer. In 1933, he performed a successful pneumonectomy at Barnes Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri. The patient was an obstetrician who received anesthesia with nitrous oxide and oxygen and was intubated. He had a central left upper lobe mass, and a left pneumonectomy was performed, with cauterization of the stump by silver nitrate. Radon seeds were left in the chest cavity to irradiate tumor cells.8 The ribs of the right chest wall were removed to allow the collapse onto the stump. This was the first published patient cured of lung cancer. Incidentally, the patient survived his surgeon, Dr. Graham, who died in 1957 of lung cancer himself.9 Over the course of the next 20 years, surgeons were resecting lung cancers more routinely. X-rays and bronchoscopy also were more commonly used.10 In the 1950s, radiation therapy of lung cancer became a more standard option as well in patients unable to undergo surgery. Despite the early advances, the mortality of lung cancer remained very high. Studies in the 1950s compared radiation therapy to surgery in lung cancer; both modalities continued to have dismal results, with mortalities more than 80%.2 Chemotherapy had its first clinical breakthrough in the 1940s for patients with leukemia. It was soon tried in solid cancers, and in the late 1950s chemotherapy, such as cyclophosphamide and busulfan, was tested in lung cancer, with disappointing results11 (Figure 1-1). Figure 1-1. History of cancer chemotherapy (ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; NCI, National Cancer Institute). (Reproduced with permission from DeVita VT Jr, Chu E. A history of cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2008;68(21):8643-53.) By the 1970s, lung cancer has turned into one of the most common causes of death. Few patients with lung cancer were referred to surgery in Great Britain and rarely cured. Often, the patients were not told that they had lung cancer, and many of the patients dying of lung cancer died at home in agonizing pain and distress. Possibly related to the frequency, fatality, and high symptom burden of lung cancer in the 1970s, the hospice movement started in the United Kingdom.2 Due to the poor outcomes treating lung cancer, increased efforts were undertaken to prevent lung cancer. Antismoking campaigners were increasingly politically active, and the media presented more and more of the rest of the Marlboro story. These campaigns helped in the stigmatization of smoking. Several decades after the initial scientific connection between tobacco and lung cancer was published, the public discussion about tobacco’s use and risks started to become louder and more influential. Once smoking was more and more negatively stigmatized, doctors and professionals were the first to stop smoking. In 1980, the consumption of cigarettes was almost half compared to consumption in the 1950s12 (Figure 1-2). Smoking was increasingly associated with socioeconomic biases in the late 1970s, and smokers were increasingly thought of as social misfits. Figure 1-2. Cigarette consumption per capita in the United States in the 20th century. (Reproduced with permission from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health 1900-1999, tobacco use—United States 1900-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(43):986-93.) Also adding to the stigma, more research in the 1980s showed the risk of passive smoking (secondhand smoking, environmental tobacco exposure). Studies, initially from Japan, clearly demonstrated the risk of passive smoking. The finding of passive smoking as a risk factor was a major contributor to the change of policies and the approach toward the tobacco industry.13 In the 1950s, the idea arose that lung cancer could be found by chest x-rays in an early stage. The idea was based on positive experience in cervical cancer screening outcomes, and the intent was to find lung cancer early in its asymptomatic stage and to have a better chance of curing it. However, none of these large studies in the United States and Europe using chest x-rays alone showed any benefit in screening to improve survival despite finding more cancers by using chest x-rays. Only in recent years have large screening trials using chest computed tomography (CT) (NLST, NELSON) been successful in shifting the stage of lung cancer to an earlier, curable stage. In the 1970s, medical oncology was established as a specialty. Based on experience in other cancers (eg, lymphoma, testicular cancer), attempts to treat lung cancer with chemotherapy again were initiated.14 Small cell lung cancer, which was described as its own entity in 1959, had in fact impressive, but short-lived, responses to chemotherapy.15,16 However, in non–small cell lung cancer no significant responses to the prevailing alkylating chemotherapy regimens were seen, and it took until the 1990s for chemotherapy to find a role in the treatment of non–small cell lung cancer. While the treatment of lung cancer was not advancing, prognostication of lung cancer was slowly adapting lung cancer staging based on tumor size, lymph-node involvement, and metastasis (TNM) at time of diagnosis. The TNM staging system was first introduced in 1943 by Dr. Paul Denoix, a breast surgeon at the Institute Gustave Roussy in Paris.17 The American Joint Commission on Cancer announced in 1968 the adaptation of the TNM system. The arrival of CT scans in the 1970s made TNM staging of lung cancer more practical. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) proposed the TNM staging system that was based on Dr. Clifton Mountain’s for a few thousand patients at MD Anderson Cancer Center.18 Since then, the IASLC has systematically expanded the database worldwide to more than 100,000 patients, with periodic updates refining its criteria of stage classifications.

1

HISTORY OF LUNG CANCER

FIRST DESCRIPTION OF LUNG CANCER

LUNG CANCER IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

FIRST BREAKTHROUGHS IN LUNG CANCER TREATMENT

THE CHALLENGE OF LUNG CANCER AND ITS GLOBAL EPIDEMIC

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree