Background

Prevalence

The prevalence of sleep problems in adulthood increases with age.1–6 In the general population, the most common types of sleep problems reported are insomnia (difficulties in initiating and/or maintaining sleep) and early morning waking with an inability to return to sleep. By survey, half of elderly individuals report some extent of sleep difficulties, including trouble initiating sleep, poorer sleep efficiency, increased time in bed, more night-time awakenings, earlier wake-up times and more daytime naps.7 Older adults primarily report difficulty in maintaining sleep and, although not all sleep changes are pathological in later life, severe sleep disturbances may lead to depression (see below), cognitive impairments and stress to partners.2, 8

Insomnia is supposedly the most prevalent sleep disturbance in the elderly, with up to 40–50% of those aged over 60 years reporting difficulty sleeping,5 with an annual incidence rate of 5% in those over 65 years old.9 General prevalence rates of insomnia in people aged 65 years and over are reported to range between 12 and 40%.10 Interestingly, prevalence rates of insomnia are higher when coexisting medical or psychiatric illness is taken into account.1, 11, 12 Foley et al.9 reported that only 7% of the incident cases of insomnia in the elderly occur without a comorbid condition. Furthermore, lifestyle changes related to retirement, the increased incidence of health problems and the use of medication all place older people at increased risk of disrupted sleep.13 The relationship between sleep problems and depression in the elderly is strong, but prone to confounding influences.1 Sleep disturbances may also be comorbid with (but not necessarily causative of) dementia, while Alzheimer-related deterioration of suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons could cause still further disturbance in sleep–wake cycle disorders.14

Basic Issues Concerning Sleep in the Elderly

In spite of the high prevalence of sleep disorders in the elderly, relatively little is known about them. This may be because gerontologists, in common with many other clinicians, are taught very little about sleep at either undergraduate or postgraduate levels.15–18

In short, sleep is a reversible state of reduced awareness of and responsiveness to the environment, which usually occurs when lying down quietly with little movement. The functions of sleep are still being debated, with a range of theories postulating physical and psychological restoration and recovery, energy conservation and a range of biological purposes. No single theory encapsulates all of these functions, and it is likely that sleep serves many purposes. For most people, a significant lack of sleep impairs both physical and psychological functioning.

Sleep problems may relate to the quality, duration or timing of sleep. Asking patients whether they feel sleepy during the day, whether they feel refreshed in the morning and whether they are sleeping at socially appropriate times provides good indicators of whether these important aspects of sleep are acceptable.

There are essentially three main sleep problems: too much, too little and the so-called parasomnias (things that go bump in the night!). However, the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd edition,19 lists more than 80 sleep disorders. This chapter focuses on the most common sleep disorders faced by people aged over 65 years and considers diagnostic and treatment issues relevant to each of them.

A variety of factors may give rise to the sleep problems reported (and often under-reported) by the elderly.2, 20 Principally, these are: medical illnesses, both chronic and acute; the effects of medication; psychiatric problems; primary sleep disorders; social changes; and behaviour patterns that are not conducive to good sleep. These problems may be exacerbated by poor handling of these problems by the patient, his or her family, doctors and other healthcare workers.

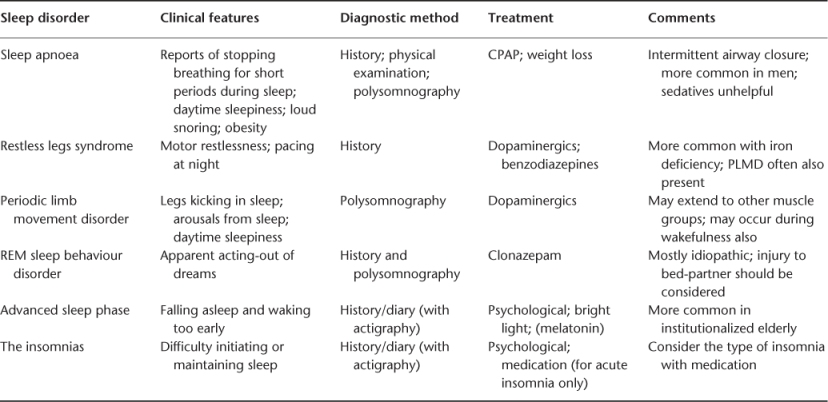

The consequences of sleep problems can be serious and costly. Lack of sleep and sedative medications have been shown to be associated with falls and accidents.21–24 The risk of medication side effects and complications related to surgery could also be detrimental in the elderly population.25 Sleep-related breathing problems, or sleep apnoea, have serious cardiovascular, pulmonary and central nervous system (CNS) effects.26 In patients with dementia, sleep disorders frequently lead to nursing home placement. Experimental studies of total sleep loss indicate that this is associated with a negative impact on mood and cognitive functioning, although as with most sleep problems, individual variations can be substantial. For ethical reasons, the number of studies in this area is limited. Partial sleep loss has been better researched and these studies are likely to be more relevant to daily life and clinical practice. A loss of sleep of between 1 and 2 h per night has been shown to lead to irritability and poor concentration. When sleep loss is prolonged, disorientation, hallucinations and inappropriate behaviour may be reported.27–31 It is important that sleep disorders are diagnosed properly and treated accordingly in view of their consequences to patients and also carers. These problems also impact healthcare costs,32 further justifying medical attention. Table 54.1 gives a brief guide to these problems and their treatments.

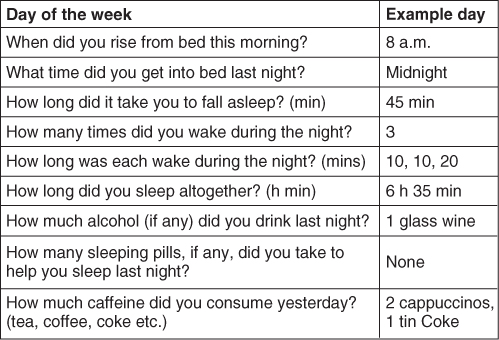

Table 54.1 Common sleep problems and their treatments in the elderly.

Sleep Structure

Normal sleep consists of a number of stages that can be simplified into rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. REM sleep is generally associated with dreaming together with lability of heart rate, blood pressure and respiration. Brain metabolism is highest in this stage of sleep, with a low-voltage, mixed-frequency non-α electroencephalogram (EEG). Spontaneous rapid eye movements are seen and skeletal muscle tone is virtually absent. REM sleep makes up ∼25% of total sleep time in adults and it is when most dreaming occurs. REM sleep episodes occur in ∼90 min cycles, with each episode increasing in duration as the night progresses. It is sometimes known as paradoxical sleep since the EEG is most like wakefulness and yet there is very little physical activity.

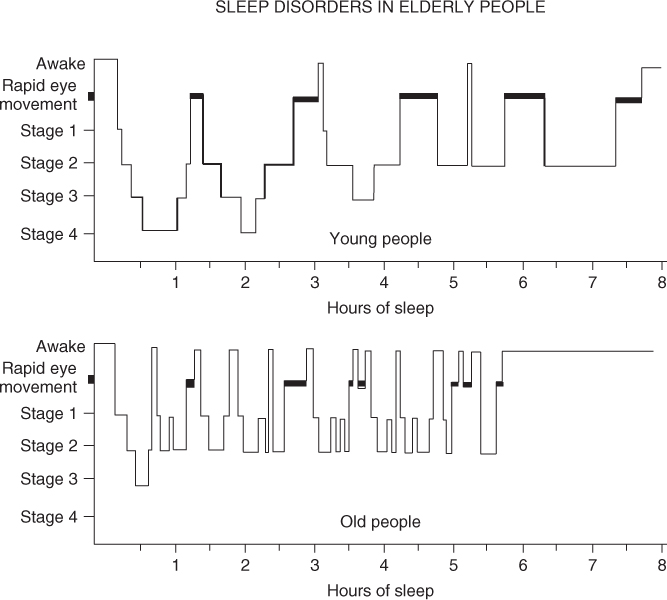

NREM sleep is subdivided into four stages of increasing depth and dominates the first half of a normal night. Stage 1 occurs at sleep onset or following arousal from another stage of sleep. The EEG is of low voltage with mixed frequencies and reduced α-activity compared with the awake state. It makes up ∼5% of the total sleep time. Stage 2 contains more slow-wave activity and sleep spindles and K complexes are seen. It makes up ∼50% of overnight sleep. Stage 3, also about 5% of sleep time, is yet more slow-wave EEG activity and stage 4 is the slowest activity and makes up ∼15% of sleep. Together, stages 3 and 4 are known as slow-wave sleep. These are the deepest forms of sleep from which awakening is especially difficult. Arousal disorders such as sleep-walking and confusional arousals arise in slow-wave sleep. These sleep stages are summarized in Figure 54.1, which shows a summative hypnogram for a 25-year-old adult and an otherwise healthy 80-year-old person for comparison.

Figure 54.1 Sleep hypnogram for a young adult and an 80-year-old. Horizontal axis = time; vertical axis = sleep stage. These subjects fall from wakefulness into slow-wave non-REM sleep in stages 1–4 before their first REM phase where most dreaming occurs. The first half of the night is dominated by slow-wave sleep and the second half by REM sleep. Thus, a patient who is limiting their sleep is more likely to be deficient in REM sleep and, therefore, more likely to have cognitive difficulties. Note the shorter, more fragmented sleep in the elderly compared with the young adult.

The most striking differences are that the younger person sleeps for a longer time, with fewer wakes during the night. The elderly person sleeps less and this sleep is highly fragmented with many arousals, some of which are for a considerable time. The older person also has very much less deep NREM sleep. Whether the older person needs less sleep at night or simply cannot get it is not currently known, but it may go some way in explaining why high levels of daytime sleepiness in the elderly is so common.2 Overall, it can be seen that sleep efficiency (the ratio of time asleep to time in bed) has fallen. The reduction in deep sleep and its replacement with lighter stage 2 sleep is of clinical significance as it is reflected in perception of sleep quality.33

The noise threshold required to waken an older person appears to be lower than in younger adults despite reductions in hearing sensitivity,34 although a study looking at this issue in people living near Heathrow Airport indicated that bed-partner behaviour was more influential than noise.35 Perhaps the elderly have a general increase in sensitivity to external stimuli, which decreases sleep quality.

Whether these sleep problems are related to gender is not yet properly understood. It appears that women report more sleep problems, although men have objectively more disordered sleep. This may be due to women reporting their sleep problems more frequently.36

The timing of sleep in the elderly is often phase advanced, that is, they generally go to sleep early and wake up earlier than they would like. The early morning waking may lead to sleep deprivation and excessive daytime sleepiness. Conversely, some older people may develop a phase delay, that is, becoming ‘night owls’ with bedtime delayed until late. This behaviour may have been accommodated in youth when the cues of bright morning light and other environmental influences were stronger; however, deterioration of light perception has weakened these cues. These patients may go on to develop very irregular sleep–wake cycles, which can be difficult to treat.

Dementia

Dementia presents additional challenges to physicians because many of the sleep changes seen in the normal ageing population are amplified. Compared with controls, older people with dementia have a longer sleep latency (time between going to bed and getting to sleep), wake up in the night more frequently and for longer periods and are more likely to fall asleep during the day.37–39 Circadian rhythm problems are also more common and 10% of older people with dementia actually sleep more during the day than during the night. These changes are often accompanied by episodes of night-time agitation and sundowning, which are among the most common reasons for admission to a nursing home.40 While there is some evidence of a possible link between sleep problems and dementia,37 individual differences are great and do not discriminate effectively between dementia and non-dementia patients. The possible causal mechanism is thought to include a degeneration of the neurons in the suprachiasmatic nuclei. Whatever the organic origin, it is likely that behavioural factors will influence sleep problems. There is good evidence that a regular day–night pattern of activity with minimal naps and optimal daytime stimulation is helpful. An exhausted carer leaving their demented relative to sleep during the day in order to give themselves a much-needed break may make life considerably worse in both the short and medium term.

Sleep disturbances in the elderly with dementia should be treated according to the specific disorder and symptom.7

Institutionalization

The link between institutionalized living and sleep disturbance is perhaps best demonstrated by the high levels of hypnotic drug consumption that have been found in hospitals and nursing homes.41 Within these institutions, sleep disturbance may be related to the act of admission itself. A period of adjustment may be required (3–4 days), as is common in many other settings where people do not sleep normally when their usual night-time environment changes. Hypnotics should not be prescribed for people who cannot sleep in a new institution unless they also have other problems. Moving to an institution is likely to be contemporaneous with a life event such as the death of a partner, discomfort or pain, any of which may have a negative effect on sleep. Noise has been shown to be a significant factor in the sleep of the institutionalized elderly and, often, noise levels in such homes are excessive. Institutions that fail to stimulate residents during the day and that have routines that are not conducive to sleep may be more likely to have sleep-disordered residents.

Assessment

As sleep can be influenced by medical conditions, chronic diseases, psychiatric disorders, medications and a host of other conditions, the first step in treating sleep disturbances in the elderly is to identify or assess the underlying problem.42 Subjective enquiries about the sleep of elderly patients should be made routinely as they are at special risk of sleep disorders, which they tend to under-report and see as normal and untreatable. More detail on the assessment of sleep disorders can be found elsewhere.43

All patients should be screened by being asked whether they sleep enough and whether their sleep is of good quality. They should be asked if they are sleepy during the day and whether their nocturnal sleep is disturbed at all. Information may be corroborated by carers or bed-partners. If any of these enquiries are positive, a fuller sleep history should be taken. This should include details of the nature of the sleep complaint, its onset and so on. Contributing factors and patterns of occurrence should be explored. The impacts of both sleep problems and previous treatments on patients and their families should be assessed. Patients should be taken through their 24 h schedules, which may elicit helpful information about timing and other aspects of their sleep. If justified, clinicians may then consider giving patients sleep diaries to complete. Sleep diaries can be helpful in understanding the times a patient goes to bed, gets to sleep, wakes in the night, wakes in the morning and gets up. Using sleep diaries, estimates can be made of sleep latency and efficiency (times between getting to bed and getting to sleep and ratio of time asleep to time in bed, respectively). There are many versions of sleep diaries available (for an example, see http://science.education.nih.gov/supplements/nih3/sleep/guide/nih_sleep_masters.pdf), but it may be helpful to customize one to attend to the particularly relevant points raised in the clinical interview. An example diary is given as Figure 54.2.

From the physical examination, attention should be paid to any systemic illness, including cardiorespiratory disease or neurological disorder such as Parkinson’s disease or stroke, which may disturb sleep. Obesity or craniofacial abnormalities may suggest upper airway obstruction and any psychiatric problems (particularly depression and anxiety) should be noted during the physical examination.

Objective investigations of sleep are not justified for all sleep disorders.44 The main indications for them are sleep apnoea, narcolepsy or periodic limb movements (PLMs). If details of parasomnias (such as REM-sleep behaviour disorder) are unclear from clinical interview, an objective check on the clinical impression is required. Generally, objective investigation is in the form of polysomnography (PSG) in a sleep laboratory, although home PSG is becoming better established and validated. When this is more accepted and widely available, home PSG may diminish the so-called first night effect, which is common when patients spend their first night in a sleep laboratory. PSG studies should include an EEG, an electrooculogram and an electromyogram in order to compile an overnight hypnogram such as in Figure 54.1.

Commonly, PSG is extended to include respiratory variables where sleep-related breathing disorders (SRBD) are suspected and anterior tibialis electromyogram if period limb movements of restless leg syndrome (RLS) are suspected.

Alternative objective measurements of sleep can be made using actigraphy, small wristwatch-sized motion detectors that distinguish wake and sleep and so are useful for circadian rhythm disorders and insomnia.45

Diagnosis and Treatment

In general, current evidence indicates that non-pharmacological treatments, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or sleep education, are more effective in the treatment of sleep disturbances in the elderly.23, 25, 46 Bright light therapy and physical exercise have also been shown to be effective in improving sleep outcomes in the elderly.47, 48 Although some evidence supports the use of pharmacology in the treatment of selected sleep disorders, most studies are limited by small, mixed samples and short trial periods of a few days.23 The most prevalent sleep disorders and their relative treatment options will be considered in greater detail here.

Apnoea, Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders (SRBD)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree