Chapter 15

Sharing Information with Friends, Family, and Coworkers

ALTHOUGH ISSUES RELATED to hereditary predisposition are deeply personal, the decisions you make may affect others. Sharing with loved ones along the way can help you shoulder the burden of hereditary risk and gain new perspective about testing, risk management, diagnosis, and treatment. It may not be easy. These are complex issues, and family dynamics can make these conversations difficult.

Sharing Risk and Genetic Testing Information with Family

Your family members may already be familiar with genetic counseling and testing. Perhaps you’ve already had conversations with them about cancer or risk, or a relative has accompanied you to healthcare appointments. If not, requesting information to build your family medical history is a good way to introduce the subject. If you’re tested for a mutation, your results may benefit your relatives. If you test positive, share this information with your family, because they may have the same mutation and high risk. You needn’t share your complete medical records and details with everyone if you prefer not to; your genetic counselor can identify information that will be most helpful to others and with which relatives you should share results. It will be helpful to disclose the type of mutation you have—a 187delAG mutation in the BRCA1 gene, for example—so if relatives decide to be tested, the lab will know what to look for. Consider not just the impact of learning that cancer runs in your family, but also the potential risk of not disclosing information.

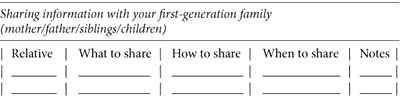

Table 15. Information-sharing worksheet

There’s never a good time to learn that hereditary disease runs in your family or that you might be genetically predisposed to one cancer or another. It’s important, however, to share what you find with other members of your family. Not all people want to know whether they have a mutation, but the decision to ignore inherited risk or take action against it should be their own. Considering what to say and how to say it may help you have a more successful conversation. Documenting the following information will help you collect your thoughts about what you want to share with family members and how best to do it. Create separate documents for discussions with your first-generation, second-generation, and third-generation relatives. (You can download and print the form illustrated in table 15 from the FORCE website.)

Coping with Family Dynamics

The loving support of those close to you can help you deal with hereditary cancer and high risk. The challenges of the situation often forge a stronger family bond and foster improved communication. Your risk management decisions may be unconditionally supported, particularly if cancer is already a much-discussed topic. For many families, the opposite is true. Not everyone appreciates knowing that they may have an unusually high cancer risk, and because the subject is disturbing, it may generate conflict. Some people prefer the ostrich approach, keeping their heads in the sand when bad news arrives, and you may not be able to change their minds.

Ideally, these issues are best approached as a family, when dialogue is nonthreatening and concerns are voiced openly. That’s not always possible, and you may feel tense or unsure about approaching the subject. The most effective way to share medical information depends on your relationship with relatives and how well they communicate with you and each other. If your family has pre-existing conflict, consider involving a professional counselor, trusted friend, or other neutral third party to help facilitate productive communication. Be straightforward. This can be difficult, especially if your relationships aren’t cordial. You may need to approach family members in different ways, depending on your level of closeness or estrangement. If you don’t know what to say, try something like, “I just learned some medical information that affects our family’s risk for disease. May I share it with you?” or “I was tested for a hereditary mutation and I have my results—are you interested?” rather than “I have a genetic mutation—you and your kids must be tested too.”

If you have a family organizer or conduit—the person who always seems to know what’s going on with everyone and passes the information along to others—you may want to speak with her first. It may be more difficult if you’ve been out of touch. If you haven’t been in contact with your cousins for twenty years, how do you call them out of the blue to say they may have a dangerously high cancer risk? When it isn’t possible or desirable to speak face-to-face with distant or estranged family members, call, send a letter, or e-mail. Clarify how you’re related, if necessary, and explain that you have medical information that may be relevant to their health. Provide them with the names of genetics specialists in their area so that they can get credible information and make their own informed decisions about genetic testing. Your genetic counselor can provide letters and information packets as examples of what to include.

It’s difficult to share your test results and risk management decisions with people who argue, aren’t interested, or tell you what you’re planning is wrong. Some people may respond with anger, suspicion, or a barrage of questions you’re unprepared to answer. Conflict may also arise when the information is perceived as upsetting or useless. The realization of your risk may scare them. One parent may agree with your course of action while the other considers it too drastic or feels guilty and avoids the topic altogether. A sister who has struggled through breast cancer treatment may tell you to proceed full steam ahead with surgery. Another who hasn’t may consider it too drastic. Well-intentioned loved ones might try to protect you by dismissing your fears or telling you to think positively. They may be afraid for you or not want to see you unhappy. It’s natural for the people who care about you to reassure you; it may be equally important for you to have a confidante with whom you can share and vent your fears. The input of others is helpful to gain perspective, but ultimately, risk management decisions are yours and yours alone.

Realize that others may not know as much as you do about hereditary cancer. They may be confused or put off by terms they don’t understand. Give relatives a chance to absorb what you’ve told them. If they feel forced to give opinions before they’ve absorbed shocking news, they may respond differently than if they have a chance to think about it and understand how they feel. If others in your family subsequently test positive, avoid pressuring them to make the same decision you did, and respect their right to gather information and make their own informed decisions. Be supportive without being insistent.

MY STORY: Sharing Information with Patience and Gentle Encouragement

After I tested positive for a BRCA1 mutation, I felt a responsibility to share my information with my uncle and cousins. I gave my uncle our family’s medical history, suggested he might want to be tested, and gave him information about genetic counselors in his area. He asked that I not share the information with my cousins before he had time to review it. As time passed, I began online contact with a cousin, although I never asked if he knew anything about our family’s mutation, because I wanted to respect my uncle’s request. I felt my cousins needed to make their own informed decisions. I wasn’t sure what I should do. I followed up with my uncle and carefully emphasized how his own genetic counseling would give my cousins information they deserved to have. He did see a genetic counselor and was tested—he doesn’t have the mutation. I was ready to tell him that I would speak to my cousins about this against his wishes if he didn’t share the information. Happily, that wasn’t necessary.

—CATHY

Asking a Relative to Be Tested

When a mutation hasn’t been identified in a family, genetic counselors identify who should be tested first to maximize information for all family members. This might not be you, even if you were the only one in the family to have genetic counseling. Asking someone else in the family to test first can be particularly challenging if you’re not close to them or if they’re uninterested. They might be concerned about health, privacy, insurance, or other issues, or upset or confused about genetic information they’ve received from people who aren’t trained in genetics. Relatives are more likely to pursue testing when they understand how their results can benefit them and others in the family. The best way to ensure they receive balanced and credible information is to direct them to a genetics expert.

When a Relative Asks You to Be Tested

If you’ve had ovarian, fallopian tube, primary peritoneal, pancreatic, or breast cancer (especially if diagnosed before age 50), you may be the most appropriate person in the family to initiate genetic testing. It’s a decision that is best made with credible and up-to-date information provided by a genetics expert.

MY STORY: I Don’t Want to Talk about It

When I learned I carried a BRCA mutation, the last thing I wanted to do was talk about it. The thought of telling my closest friends made my stomach turn. So I hid the piece of paper that said “positive for a deleterious mutation” and did everything possible to forget that I was basically a ticking time bomb. They give you the information and then they say, “Don’t panic. Don’t be neurotic. Don’t be paranoid.” But your body can go off at anytime, and that pressure starts right away.

—JOANNA

Issues for Spouses, Partners, and People You Date

Telling your partner or spouse about your high risk or your plans to deal with it can strongly affect a relationship. While devastating news can unravel a relationship with weak foundations, it often strengthens the caring bond two people share. In a study of young single women who had genetic testing before marriage, participants reported fear and anxiety prior to sharing their BRCA mutation status with dating partners. Yet many of the women felt that sharing their status had positive effects on their relationships.1

A partner who seems uninterested or uncaring may be fearful, particularly if this is the first experience with a serious health issue. He may be afraid of losing you. Often partners feel distressed by a medical issue because they have no control over it and can’t fix it. They don’t know how to deal with something that disrupts their normal lives, so they ignore it. Your tone and attitude make a difference. Calmly explain the circumstances. Talk honestly about what you need and how he can best support you. Talk about how your oophorectomy may affect your plans for children, what breast reconstruction involves, or what side effects you might expect from chemoprevention. Invite your partner to participate in your research, doctor visits, and decisions. Although it’s your body, the life disruptions caused by a BRCA mutation affect you both, and hopefully, you’ll overcome these issues together.

Sexuality, Intimacy, and Body Image

For most of us, sexuality and sensuality are intertwined, bound together by the intimacy we feel with another person. When life throws us a curve (like inheriting a BRCA mutation) and disrupts our normal lives, shared intimacy is often one of the first casualties. Preventive choices or the aftermath of radiation, chemotherapy, chemoprevention, or surgery may shake your otherwise confident feelings about your body image, self esteem, libido, and ultimately your ability to be sexually satisfied. Intimacy may be the last thing on your mind as you cope with mammograms, MRIs, biopsies, or hot flashes after your oophorectomy. If you’ve had a mastectomy, you may dread that first moment of naked intimacy: the revelation that your breasts are gone or that your reconstructed breasts can’t sense your partner’s touch.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree