Chapter 56 Sexually Transmitted Human Papillomavirus Infection

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) represent a large group of viruses that infect mostly the squamous epithelia of the body. They cause latent, asymptomatic infections as well as neoplasms that range from benign warts to malignant squamous cell carcinoma, particularly of the cervix. A subgroup of HPVs has a predilection for the anogenital tract (Table 56-1). Because these genital HPVs are mostly sexually transmitted, they are likely to be encountered in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected population; immunosuppression and immunodeficiencies tend to be associated with HPV diseases that are more florid and difficult to eradicate or control than in the immunocompetent host. Consequently, sexually transmitted HPV diseases in the HIV-infected patient create management problems for the practitioner. This chapter describes the resources and approaches that are available.

Table 56-1 Genital HPV Types and Their Disease Association

| HPV Types | ||

|---|---|---|

| Disease | Frequent Associationa | Less-Frequent Association |

| Condylomata acuminata | 6, 11 | 30,b 42, 43, 44, 45,b 51,b 54, 55, 70b |

| Intraepithelial neoplasias | ||

| Unspecified | 30,b 34, 39,b 40, 53, 57, 59,b 61, 62, 64, 66,b 67,b 68,b 69, 71, 72, 82b | |

| Low grade | 6, 11 | 16,b 18,b 31,b 33,b 35,b 42, 43, 44, 45,b 51,b 52,b 74,c 86, 87, 89, 90, 91 |

| High grade | 16,b 18b | 6, 11, 31,b 33,b 35,b 39,b 42, 44, 45,b 51,b 52,b 56,b 58,b 66b |

| Cervical (and other genital) carcinomas | 16,b 18b | 31,b 33,b 35,b 39,b 45,b 51,b 52,b 56,b 58,b 59,b 66,b 68,b 70,b 73,b 82b |

| Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis | 6, 11 | |

a The distinction between frequent and less frequent is arbitrary in many instances. Large descriptive statistics of HPV type distribution by disease are not available for the majority of HPV types. Moreover, many HPV types have been looked for or identified only once.

b Types with high malignant potential or only isolated in one or a few lesions that were malignant.

c Type first recovered from immunosuppressed or HIV-infected patients.

PATHOGEN

HPVs are circular, double-stranded DNA, nonenveloped viruses that belong to the Papillomavirus genus of the Papillomaviridae family. The nucleic acid is enclosed in a 55 nm diameter icosahedral capsid composed of 72 pentamers. One strand of the DNA encodes all the open reading frames (ORFs). The genome can be divided in three parts. The first is a noncoding region, or upstream regulatory region (URR) that contains the origin of replication as well as a promoter sequence and binding sites for various viral and cellular regulatory proteins. Downstream of the URR is a group of ‘early’ ORFs (E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, and E7) that encode for nonstructural proteins. E1 is involved in viral replication, as is E2, which also regulates viral expression. E4 produces an abundant cytoplasmic protein that associates with the intermediate filament network but whose role is obscure. E5 is believed to contribute to malignant transformation, a role that has been well established for E6 and E7 of high-risk oncogenic HPVs. The E6 protein binds to p53, a major tumor suppressor protein, and induces its degradation. Similarly, the E7 protein binds and inactivates other tumor suppressor molecules, the retinoblastoma protein (pRB) and pRB-associated proteins. Both p53 and pRB exert essential control on cellular replication and apoptosis. E6 and E7 also interact with many other cellular proteins. The late ORFs are the third component of the genome and are made up of two ORFs, L1 and L2, encoding for structural proteins: the major and minor capsid proteins, respectively. In malignant lesions, HPV DNA is typically found integrated into the host genome. This integration always disrupts the E2 ORFs but never the E6 and E7 ORFs, which become unregulated.

The classification of HPVs is based on genotypes rather than serotypes. HPV types are distinct if they share less than 90% of the DNA sequence homology for the L1 ORF with one another. More than 200 HPV types have been identified so far, and 10 types have been characterized. Each type tends to be associated with a particular tissue specificity, pathology, and oncogenic risk (Table 56-1).

The second group corresponds to epidermodysplasia verruciformis, a rare genodermatosis. It first manifests in late childhood as flat wart-like lesions, plaques, or pityriasis versicolor-like lesions that in the sun-exposed areas have a high risk of evolving into malignant squamous cell carcinomas in the fourth and fifth decades. The immunosuppression of HIV infection may cause a phenocopy of the disease.1

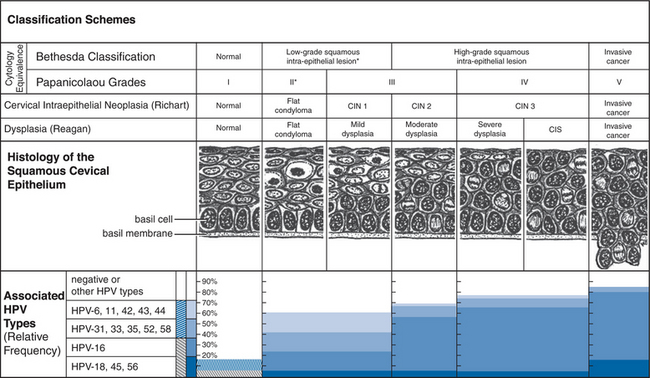

The intraepithelial neoplasias are a group of conditions defined by the proliferation in the anogenital stratifie depithelium of basaloid (basal-appearing) cells with an excess of often abnormal mitotic figures (dyskaryosis). Three grades are recognized, from the less to the more severe, based schematically on the proportion of the epithelium involved in this process. Thus the process involves up to the lower third of the epithelium in grade 1 (I), more than one-third but less than two-thirds in grade 2 (II), and more than two-thirds in grade 3 (III). In carcinoma in situ (CIS), a form of intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3, the full thickness of the epithelium is involved. Breakage of the basement membrane by this cellular proliferation represents invasion and the ultimate stage of evolution of an intraepithelial neoplasia: squamous cell carcinoma. Originally devised for the cervix (Fig. 56-1), this simple histologic classification scheme is also used for other locations, giving rise to various acronyms: CIN for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, VAIN for the vagina, VIN for the vulva, PIN for the penis, and AIN for the anus. Other conditions developing on the external genitalia are simply clinical variants of intraepithelial neoplasias. They include bowenoid papulosis (pigmented papules with a condylomatous cytoarchitecture); Bowen disease (CIS presenting as a flat, red to brown plaque, with well-demarcated borders and a scaly surface); and erythroplasia of Queyrat (Bowen disease of the glans penis). Condylomas and intraepithelial neoplasias of the cervix typically arise in the transformation zone, the virtual space between the location of the squamocolumnar-epithelial junction at birth and the current location of this junction, which with age recedes toward the endocervix. Similarly, in the anus, it is in the area of squamous metaplasia, at the junction of the squamous and glandular epithelium, that one finds AIN and carcinomas.

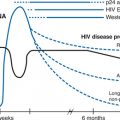

If only based on the fact that they are in part caused by the same HPV types, these diseases are related. Another relation, histopathologic, has been particularly well documented for the cervix, where a lesion may progress from condyloma or CIN 1 to CIN grades 2 and 3, and cancer. This progression is not necessarily steady, it may not even occur, some of its stages may be missed, and up to grade 3 it may revert. Importantly, the risk of progression or regression is related to the HPV type causing the process, molecular variants within HPV types, HPV viral load and persistence, as well as possibly other factors such as smoking, use of oral contraceptives, immunogenetics, diet, and co-infections. Figure 56-1 illustrates the relation between HPV type and disease grade in greater detail in the case of the uterine cervix involvement.

Two minor groups of diseases are related to the genital HPV diseases because they are caused by the same HPV types and are mostly sexually transmitted: recurrent respiratory papillomatosis and oral condylomas. Although risk factors for the acquisition of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis include receptive oral sex in adults and vaginal delivery in children, for unclear reasons the disease seems to be rare in HIV-infected individuals. Oral HPV diseases include condylomas resulting from sexual transmission. Only histology helps distinguish them from other oral benign HPV-associated lesions such as squamous papillomas and verruca vulgaris.2 Heck disease (focal epithelial hyperplasia), an uncommon florid oral papillomatosis predominantly caused by HPV type 13, has been described in HIV patients associated with HPV32.2

Anogenital HPV infections are particularly common in the general population, but the prevalence varies with the method of diagnosis and, as would be expected for agents that are mostly sexually transmitted, the age of the population. For example, in one study, using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay, 49% of women between the ages of 20 and 25 years had HPV in their cervix, in contrast to 34% of women 26–50 years of age.3 Based on cytology, the rates fall to ∼1–5% depending on age and diagnostic criteria.4 It is estimated that ∼1% of the population has condyloma acuminatum.4 These numbers exemplify the large size of the virus reservoir in the population at large. Sexual transmission is by far the major mode of dissemination and although direct evidence is lacking, it is probably more efficient if the infection causes full-blown disease rather than latency or subclinical disease.

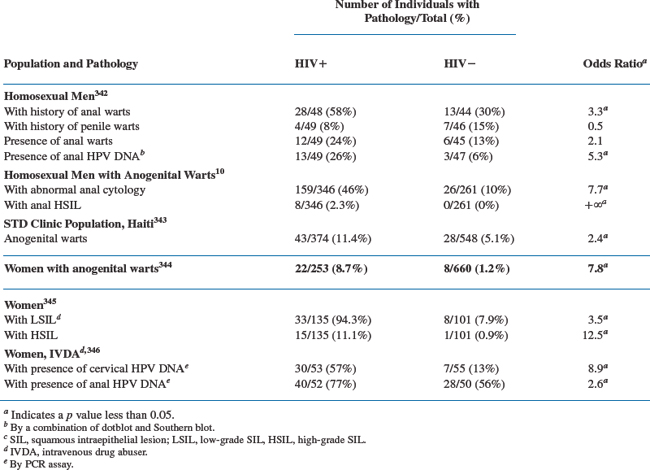

Three types of anogenital HPV diseases are clearly overrepresented in the HIV-seropositive population compared to the seronegative population: condyloma acuminatum, AIN (in men, and in women to a lesser extent), and CIN (Table 56-2).5–19

A large population survey has shown that in patients who have AIDS, the relative risks of in situ or invasive squamous cell carcinomas are increased in several anatomic locations: cervix, vulva/vagina, anus (both genders), penis, and (men only) tonsils and conjunctiva.14

These findings are consistent with the observation that HIV infection is associated with anogenital infections involving high-risk rather than low-risk HPV genotypes, and with more persistent and high HPV viral loads.7,12,15–27 Other factors, such as smoking and young age, independently contribute to the risk of anogenital HPV infection and disease.11,15,28 Although anal intercourse is a risk factor for anal HPV infection and disease in men and women, high prevalence of these conditions still exist in its absence.29,30

The nature of the link between HIV and HPV infections seems to be behavioral and immunologic, but the details are not well defined. Because both infections are sexually transmitted, it is obvious that they share some of the same behavioral risk factors. However, if oral sex seems to be a risk factor for adult-onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis in the general population, it is not clear why this entity is not more common in HIV-infected patients.31 HIV infection depresses the immune defenses that control HPV infections. Accordingly, the more severe the HIV infection (as measured by the progression to AIDS, CD4+ cell count, or HIV viral load) the higher is the risk of finding high-risk HPV DNA in the anogenital tract, condylomata acuminata, or preinvasive squamous cell carcinomas in the cervix and anus of men and women.32–35 It is also not surprising that because of the HIV-induced immunosuppression, HPV diseases in these patients tend to be more severe and intractable, and they recur more frequently.36–45

This simple biologic explanation is not sufficient, however, otherwise the risk of invasive cervical cancer should rise as patients progress to AIDS. On the basis of that expectation, in 1993 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had included cervical cancer as an AIDS-defining illness.46 The failure for the expectation to materialize clearly has been a surprise. It has since been reasoned that because cervical cancer takes about a decade to develop in the general population, the limited survival of HIV patients did not permit a sufficient number of cervical cancers to occur for the trend to be detected. This interpretation is losing much strength because larger surveys still did not detect a trend.14,47 It has been also proposed that intensified screening programs in combination with improved antiretroviral treatments might have curbed the progression of CIN to invasive cancer. However, the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) had no effect on the incidence of invasive cervical carcinoma in an Italian cohort study.48 In Africa where cervical cancer screening programs and antiretroviral therapy (ART) are rarely available, the increase in the incidence of cervical cancers in the HIV population has been much more limited, when present, than in the developed world.49,50 We do not know if, when noted, this increase correlates with the degree of immunosuppression or some important covariates.51,52 Some of those covariates might be independent of the stage of HIV disease and be linked to the possible direct enhancing role of HIV proteins on HPV oncogenesis, or the seeming ability of HPV16, the most oncogenic HPV, to evade the immune system.53,54 Some have argued for abandoning the characterization of cervical cancer as an AIDS-defining cancer, but this does not change the need for attentive screening for HPV-related anogenital cancers in the HIV population.55

DIAGNOSIS

All available treatment modalities are directed at eradicating HPV disease rather than HPV infection. Therefore, disease diagnosis is more relevant than proving HPV infection. To detect HPV disease, the clinician depends on clinical methods, cytology, colposcopy, and histology. It is clear that the diagnosis of HPV infection and the typing of its agents are likely to play an important role in the future. Because HPVs cannot yet be grown and propagated in vitro, the diagnosis of HPV infection depends on the detection of HPV DNA. Serology is useful in epidemiology but has no place in clinical practice.

Clinical Diagnosis

Diagnosis of anogenital HPV diseases in HIV-infected patients requires a history and physical examination. The history should focus on symptoms of the anogenital area (itching, discomfort, pain, bleeding, change of appearance) and inquiries about changes that affect sexual intercourse, urination, and defecation. Anorectal symptoms are particularly common in patients with AIN grade 3 and minimally invasive anal cancer, and should not be ignored.56 If a diagnosis has already been established, one should assess its psychological impact and note the treatment received for the present condition and possible previous occurrences. To ensure future treatment compliance, it is wise to inquire about the patient’s experience with prior treatment. It is also important to document how the diagnosis was made (e.g., clinically, cytologically, biopsy), because it may be open to revision. A sexual history should identify age at first intercourse, number of past and present sexual partners, sexual practices, and use of barrier methods of contraception and sexually transmitted disease (STD) prevention. The history and treatment of other STDs should be also recorded as well as the histories of warts, intraepithelial neoplasias, or cancers in the sexual partners.

The physical examination of the male patient is typically carried out with the subject leaning back against the end of the examining table and standing in front of the seated clinician. For the anal examination the patient turns back, legs apart, the torso bent and applied against the table. A tilting, proctologic examination table is helpful, if available. Alternatively, the patient can be examined in lateral decubitus and genuflected. For the female, the entire examination is conducted with the patient in the lithotomy position, legs placed in stirrups. Good lighting is essential. The examiner should wear gloves; the use of aprons, gown, mask, and eye-protective equipment should be tailored to the circumstances of the examination and to the additional procedures performed. Physical examination of the external genitalia can be augmented by the application for 1–5 min of gauzes soaked in 3–5% acetic acid (white vinegar). This is most helpful for detecting small or maculopapular HPV lesions because they tend to be acetowhite, particularly on the nonkeratinized (‘mucosal’) epithelia. However, acetowhitening is not a specific test when used alone and treatment should only be directed at papular lesions consistent with warts. The use of a magnifying glass or, better, a colposcope assists the diagnosis further. An anoscopic examination should be done if there are anal symptoms, a history of anal-receptive intercourse, or perianal warts (see section on Therapy).57 Anoscopic diagnosis requires some familiarity, and proper evaluation should be left to experts. The diagnosis can be aided with a colposcope and prior application of 1% acetic acid, a procedure called high-resolution anoscopy.58 Because lesions rarely extend beyond the pectinate line, a sigmoid examination is not routinelyindicated.59,60 In women, a speculum examination of the vagina and cervix should be done to at least rule out gross abnormalities and obtain a Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, if indicated (see section on Prevention). Application of acetic acid and use of a colposcope aid the diagnosis considerably, but such skills are usually beyond those of the primary care practitioner. The visual inspection of the anus, vagina, and cervix should be completed by a digital examination. An examination of the oral cavity should be considered to exclude associated oral warts. Whenever the proper diagnosis is in doubt, especially if intraepithelial neoplasia or cancer is in the differential diagnosis, a biopsy should be considered. This particularly applies to pigmented lesions and anal, vaginal, or cervical lesions. The use of anatomic diagrams to document the lesions is strongly recommended because they facilitate subsequent evaluations.

Cytology and Colposcopy

Cervical cytology in the form of the Pap smear is an important tool for detecting and managing HPV diseases of the cervix. Several methods and instruments have been designed to collect the cervical cells. Ideally, one uses a wooden Ayre spatula. The longer lip is placed in the cervical os, and the spatula is rotated 360°. A Dacron swab or, better, an endocervical brush is then introduced in the os and rotated 180°. The material collected on the spatula and on the brush are then respectively smeared and rolled on the same side of a glass slide bearing the patient’s identification. The slide is immediately exposed to a fixative, either with a spray or by immersion in a transport jar filled with alcohol. A Cervex brush (‘broom’) substitutes advantageously for the Ayre spatula and brush when the cells are collected for liquid-based cytology (ThinPrep; AutoCyte). This newer technology allows better preparation of the sample, increases the sensitivity for the detection of squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL), but is more costly and time-consuming than traditional cytology, which it has largely supplanted.61,62 Figure 56-1 illustrates the correspondence between the various histologic and cytologic classification schemes for HPV cervical lesions. The Bethesda classification, established in 1988, and revised in 1992 and 2001, calls for establishing the adequacy of the sample, categorizing the cytology, and recommending management and follow-up (http://www.bethesda2001.cancer.gov).63 Squamous cell abnormalities fall into four categories: (1) atypical squamous cells (a) of undetermined significance (ASC-US), or (b) but high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) cannot be excluded (ASC-H) (both subcategories used to be grouped as atypical squamous cells of unknown significance (ASCUS); (2) low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL); (3) HSIL and (4) squamous cell carcinoma. The sensitivity and specificity of the Pap smear for the detection of CIN in HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative women appear to be similar.64,65 The Pap smear is not a diagnostic test, but because it is inexpensive and can be repeated frequently it remains an excellent, so far essential, screening tool.

Colposcopy plays a role in the evaluation of an abnormal Pap smear. In that context, it has two connected purposes; the visual identification of lesions and the selection of biopsy sites for histologic confirmation. The colposcope is simply a binocular microscope with a long focal length (300–350 mm) and its own light source that permits detailed inspection of the cervix exposed with a vaginal speculum. With its complete implementation, the colposcopic examination includes application of 5% acetic acid and possibly an iodine (Lugol) solution (Schiller test). Lesion identification is based on one of several scoring systems that rely on elements such as color, shape of the margins, and vessel appearance. If abnormalities are present, colposcopy should be supplemented by biopsies for a more reliable histologic diagnosis. The performance characteristics of colposcopy in HIV-seropositive women might not be as good as in HIV-seronegative women.65

Cytologic screening has been extended to the anal canal. The technique requires introduction of a Dacron swab moistened with saline or water, or a cervical cytobrush, into the anal canal more than 2 cm from the anal margin.66 The swab is rotated as it is withdrawn and then rolled over a glass slide or shaken in a liquid cytology transportation medium (ThinPrep; Auto Cyte) vial bearing the patient’s identification. The slide is promptly fixed and processed as for a Pap smear. The test can be self-administered.67 The sensitivity and specificity of anal cytology for the diagnosis of AIN (excluding ASCUS) in HIV-seropositive homosexual men are 46% and 81%, respectively.68 Therefore, as for the cervix, anal cytology should be viewed more as a screening tool than a diagnostic tool. Anal cytology screening for SIL in HIV-positive and HIV-negative homosexual and bisexual men appears to be cost-effective when theoretical models are analyzed.69,70 Nevertheless, as appealing and promising as it is, it cannot be widely recommended at this time for several reasons.71,71a The interpretation of anal cytology and histology suffers from poor to moderate inter- and intraobserver reliability.72 There is a lack of clinically validated screening strategies adapted to the various populations at risk. We also do not know the natural evolution of high-grade anal SIL, which also are prone to recur after treatment.73 In addition, the medical and surgical treatment options are limited yet their selection is not codified or validated by comparative studies. Furthermore, their impact on the prevention of anal cancer is largely unknown. Another difficulty is the need to train physicians on how to evaluate, biopsy, and treat a cytology-positive patient with anoscopy under magnified optics (high-resolution anoscopy).

Histology

Histologic diagnosis is used to confirm the diagnosis of HPV disease. The histologic material may be an operative sample or a biopsy specimen obtained by scalpel, scissors, punch, forceps, or electrosurgical or laser excision. Buffered formalin is the fixative of choice if subsequent in situ hybridization techniques are contemplated. Although diagnostic criteria are well recognized, particularly for the cervix, sampling variations, the size and condition of the sample, and intra- and interobserver variabilities can still affect the accuracy of the diagnosis. Furthermore interobserver reproducibility of cervical histology is no better than that of cervical cytology and is only moderate with both techniques.74 Anal cytology and histology suffer from the same limitations.72

Nucleic Acid Detection Assays

Nucleic acid detection assays permit the diagnosis of HPV infection and typing of the virus. The material submitted for analysis can be cells collected from scraping, cervical lavage, or tissue. The Hybrid Capture II assay (Digene Diagnostics) is the only test approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that is available to the practitioner. This proprietary assay is based on liquid phase hybridization. Cells or DNA extracted from the tissue sample are denatured in an alkaline solution. Two pools of RNA probes are added in parallel. Probes in pool A hybridize low-risk HPV types (6, 11, 42, 43, 44), whereas in pool B they hybridize high-risk HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68). The hybrid DNA–RNA is immobilized by an antibody coating the wells of a microtiter plate and is recognized by an antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase that generates a chemoluminescent signal. The assay is rapid, resilient to cross-contamination, and quantitative. Investigators have also developed various assays based on the PCR for HPV DNA detection and typing. The Hybrid Capture II assay and PCR have comparable sensitivities, but PCR is more type-specific.75,76 HPV DNA testing has been recommended in the management of ASCUS.77 Since 2003, HPV DNA testing is also approved by the FDA to be used simultaneously with liquid-based cytology in women who are 30 years and older. The place of HPV typing for the anus is not established, but does not appear to be promising.78

THERAPY

Approach to Therapy

Condyloma Acuminatum

Goals of Therapy

The psychological effect of condyloma acuminatum in the general population tends to be overlooked, yet it is an important reason for seeking treatment.79 In fact, about half of the patients report a significant psychosexual impact either before or after treatment.80–83 It is not known if the HIV-seropositive population is similarly affected, or if the social stigma of an additional STD is a reason for seeking treatment.

In the general population three-fourths of patients are asymptomatic, and treatment is initiated for cosmetic reasons.84 There are no data on the frequency and nature of symptoms in HIV-seropositive patients, but symptoms such as itching and less frequently burning, pain, discomfort, discharge, bleeding, and dyspareunia may be indications for treatment. In pregnant women, warts may partially obstruct the birth canal or compromise hemostasis and repair of lacerations and incisions after delivery.

Treatment should be directed at the disease, not the infection, although the latter may be more extensive than the former.85–87 Current treatments are considered ineffective for eliminating HPV infection. For example, laser vaporization of the entire mucosal surface of the lower genital tract of women with histologic evidence of HPV infection failed to eradicate the infection in most patients, and it was associated with severe morbidity.88 Similar disappointing results have been obtained in men.89

No information is available on the prevalence of condyloma acuminatum and other anogenital HPV diseases in the sexual partners of HIV-seropositive patients with condyloma acuminatum. However, several studies in the general population have indicated that 40–70% of sexual partners of patients with anogenital HPV disease have lesions, which are macroscopic in half the cases.90,91 Treating the male partner of women with CIN or subclinical genital HPV infection has failed to have an impact on the patient’s condition.88,92 Whether the reverse situation wherein treating the female partner helps the male patient is unknown. At present, the CDC does not advocate tracing and treating sexual partners for HPV disease.93 The sexual partners of HIV-seropositive patients are more likely to be evaluated for HPV disease when traced for HIV infection or other STDs.

There is an association between condyloma acuminatum and the presence of cervical or anal intraepithelial neoplasias and cancer in HIV patients.94 As yet there is no other evidence to indicate that treatment of condyloma acuminatum, even intra-anal, has an effect on these conditions. Vulvar and penile cancers are too rare for studies to be able to gauge an effect from treating condyloma acuminatum. Thus so long as one can be reassured that it is condyloma acuminatum, not intraepithelial neoplasia or cancer, cancer prevention should not be a reason for treating condyloma acuminatum.

Risks of Therapy

Therapeutic abstention is definitely an option to consider, provided one is confident that the patient has only condylomata acuminata, not intraepithelial neoplasia or cancer, and that regular follow-up is possible. Although HIV-seropositive patients may have more recalcitrant and longer-standing disease than their HIV-seronegative counterparts, this is not uniformly the case.36,41 The natural history of condyloma acuminatum is poorly known, especially among those who are HIV seropositive. In the nonimmunocompromised host, the experience with the placebo recipients in controlled clinical trials suggests that one can expect a 5–20% rate of spontaneous resolution of condyloma acuminatum within 3–4 months.95–100

Other Anogenital HPV Diseases

The three general principles that apply to the management of intra-anal warts and anogenital intraepithelial neoplasias are simple. First is the need to make a tissue diagnosis. Biopsies are essential, but sampling errors are a problem. For example, cervical punch biopsies of the cervix may underdiagnose HPV disease in HIV-seropositive women.101 The second principle is to apply the proper treatment, which should be left to experts.102 The third, extremely important principle is to follow the patient on a regular basis. In at least half of the HIV-seropositive patients treated for CIN, disease recurs, with a risk that increases with the falling CD4+ cell count, and disease involvement of the margins of the resected tissue.37,42,44,45,103 Recurrence is also the typical outcome for anal HSIL lesions.73 Screening is part of the management for cervical HPV diseases.104

Effect of HIV Antiviral Treatment on HPV Disease

The effect of antiretroviral treatment (HAART in particular) on the natural history of anogenital HPV diseases is confusing. The conflicting data have been recently reviewed by Heard and colleagues.105 In summary, HAART might improve the resolution of genital warts and of vulvar neoplasia.106 The effect on CIN varies for reasons that are still unclear from nonexistent to favorable. HAART generally does not correlate with a positive outcome of HPV-associated anal disease.107–111 The incidence of oral warts appears unaffected or increased with HAART.112

Available Treatment Modalities

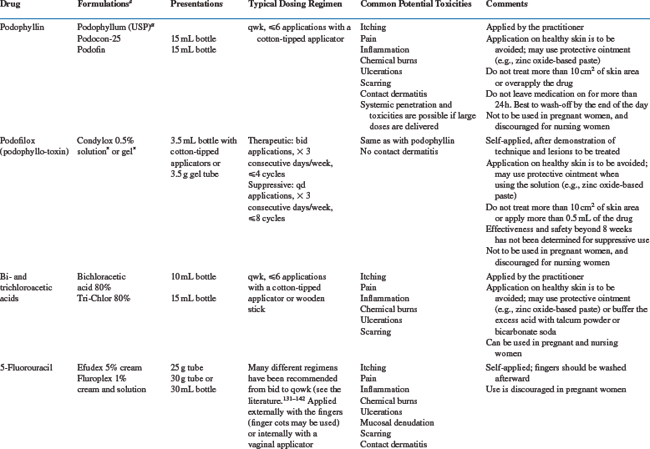

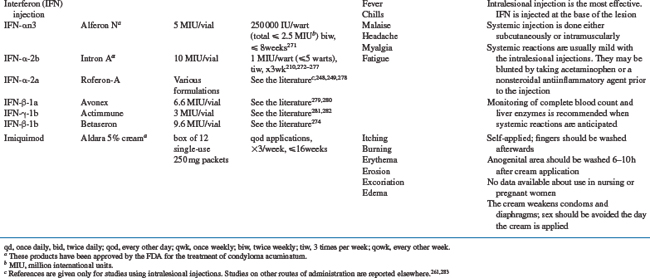

Treatment modalities for condyloma acuminatum are many, a reflection of the limitations of them all.113 To choose among them is complicated by the relative paucity of well conducted comparative trials. Even some commonly used treatments have never been submitted to a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. The most commonly used or best studied treatment modalities are emphasized in this section. The available information presented has been derived from studies done largely, if not exclusively, in immunocompetent patients. For the most part, one can only extrapolate this knowledge to the HIV-positive population, remembering that a successful treatment response may be less frequent, recurrences more common, disease more extensive, and side-effects different.114,115 Table 56-3 summarizes practical information on the drugs commonly used to treat condyloma acuminatum.

The CDC, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) have issued human papillomavirus diseases treatment recommendations for HIV-infected adults and adolescents.102

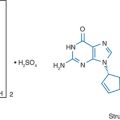

Podophyllin/Podofilox

Podophyllin is a natural product extracted from the rhizome of Podophyllum peltatum or P. emodi. The two major groups of compounds found in podophyllin resin are flavonols and lignans. The antiwart activity is limited to the lignans and principally to podophyllotoxin, which represents ∼10% of the preparation.116 Podofilox is now the generic name of podophyllotoxin. Like colchicine, it binds tubulin and inhibits microtubule polymerization.116 This causes disruption of the mitotic spindle and mitosis, and there is disruption of the other cellular functions dependent on the integrity of microtubules. In addition, podofilox may directly damage HPV DNA.117

Table 56-3 describes how podophyllin and podofilox are used and prescribed for treatment of condyloma acuminatum. Being a purified, standardized product, podofilox has a more predictable effect than podophyllin. It is also more active and less toxic on a weight basis, permitting the drug to be applied by the patient.116,118 The toxicity of podophyllin is well documented.116,118 In addition to the local side-effects listed in Table 56-3, the medication can be readily absorbed through the skin and cause systemic side-effects including nausea, vomiting, sometimes irreversible motor and sensory neuropathies, seizures, coma, and death. The drug can also be toxic to the bone marrow, the lungs, and the kidneys. It is contraindicated during pregnancy, because of its mutagenic and abortifacient properties. Skin biopsies obtained after application of podophyllin should be interpreted with great caution. The drug causes skin necrosis, and the presence of large keratinocytes with disrupted chromatin (podophyllin cells) or mitoses can be misinterpreted for intraepithelial neoplasia.119,120 Podophyllin has been associated with contact dermatitis caused by the benzoin vehicle or guaiacum wood contaminants. Podofilox is much less toxic than podophyllin.116,118

Since the 1940s there have been many reports on the use and efficacy of podophyllin and, later, podofilox for the treatment of anogenital warts.116,118 The efficacy can be best ascertained from the many randomized comparative trials. Reported rates of a complete response to podophyllin vary widely, from 22% to 100%, but mostly range from 35% to 50%. They are inferior to those of the other standard forms of treatment (excisional surgery, electrodesiccation, cryotherapy, podofilox). Recurrences are common (typically 40–70%), so the net complete response rates are even lower, ranging from 25% to 45% (the longer the follow-up and the larger the HPV viral load, the higher the recurrences rate).121 Overall, podofilox is more effective than podophyllin, but the complete response rates associated with its use range from 20% to 100%, typically 60–70%; and recurrences are common (30–50%), bringing the net complete response rate to a common range of 30–50%.116,118,122 Prophylactic application of podofilox after the lesions disappear does prevent recurrences.123 Podofilox 0.5% self-applied once a day for 3 consecutive days a week for 8 weeks after condylomata acuminata had been eradicated with either podofilox or cryotherapy resulted in only two of 21 patients (19%) having recurrences. In contrast, 12 of 24 patients (50%) treated with only the vehicle recurred. The durability of this effect is unknown. The abandoning of podophyllotoxin in favor of podofilox has been argued in view of the ease of application, and the toxicity and efficacy data.116,118

Information on the use of podophyllin or podofilox in HIV-seropositive patients is limited. Beck et al treated 31 patients with anal condylomas using 5% podophyllin and found a 26% recurrence rate at a mean 12 months later.124 Orkin and Smith observed worse results in their study; 17 of their 21 patients (81%) treated with podophyllin failed.125 Podofilox has also been associated with a poor outcome. After a single cycle of podofilox 0.5% solution applied twice a day for 3 consecutive days, eight of 18 HIV-seronegative patients (45.5%) were free of condylomata acuminata after 6 months of follow-up compared to only one of 15 HIV-seropositive patients (P = 0.02).40 Podophyllin has been used successfully in the eradication of bowenoid papulosis in a 9-year-old child who had previously failed to respond to imiquimod.126

Bi- and Trichloroacetic Acids

Bichloroacetic and trichloroacetic (TCA) acids have long been used, predominantly by gynecologists, but also by proctologists. They induce acid hydrolysis, which is responsible for their keratolytic action. They may bind to the cellular proteins, acting as a cauterizing, fixative agent.127 They also readily destroy HPV DNA. Only one of 14 condyloma acuminatum patients (7%) treated in vitro by TCA yielded HPV DNA by PCR.117 Table 56-3 lists dosages and administration of bichloroacetic acid and TCA, and their side-effects. Discomfort, ulcerations, and scabbing are some of the adverse reactions that occur in about two-thirds of the patients.128,129 They are more common than with cryotherapy. Widely used, these agents have been submitted to limited evaluation, and only TCA has been compared to other standard therapies.128–130 TCA appears to be equivalent to cryotherapy in terms of the complete response rate (,65–80%) and recurrence rate, with about half of the patients remaining free of disease.128 Acids are safe for the treatment of pregnant women.

5-Fluorouracil and Nucleoside Derivatives

Various topical regimens with 5-FU have been applied for the treatment and prophylaxis of condyloma acuminatum, vaginal warts, and intraepithelial neoplasias of the vagina and cervix.131–142 5-FU has been applied twice daily to weekly for durations ranging from a few days to 10 weeks. The frequency and nature of the side-effects depend on the regimens used and the sites treated. Pain, itching, burning, and hyperpigmentation are the most common local adverse reactions, affecting approximately half of the patients. More serious reactions have also been noted, such as contact and allergic dermatitis and chronic vaginal ulcerations,143–146 which has discouraged many practitioners from using this drug. Twice-weekly applications are much better tolerated than daily applications, without an apparent difference in efficacy.140 Reportedly, fair-skinned individuals are particularly prone to local side-effects.147 Rarer but significant complications should be mentioned: leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, toxic granulations, and eosinophilia as well as the development of vaginal adenosis and vaginal clear cell carcinoma.148 Administration of 5-FU has not been associated with congenital malformations, but the safety of this drug during pregnancyis not established.149

Intrameatal warts seem to be particularly responsive to 5-FU treatment, usually administered daily for 3–14 days.133,134,150 Krebs observed that 16 of 20 patients (80%) with vaginal warts had a long-term (median 16 months) complete response after treatment with bedtime application of 1.5 g of 5% 5-FU cream once a week for 10 weeks.139 Similarly, intravaginal or vulvar 5-FU prophylaxis against recurrences after treatment of vaginal and vulvar warts, respectively, appeared to be effective in HIV-uninfected patients.138,151 In the HIV population, a placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy of 1% 5-FU gel in 60 women with intravaginal warts, all of whom were receiving zidovudine 250 mg three times a day.152 The 5-FU preparation was self-administered for 4 weeks: every other day 3 times a week at bedtime by deep intravaginal application of 4 mL. Sixteen weeks after treatment initiation the complete response rates were 83.4% in the 5-FU group and 13.3% in the placebo group. Side-effects included mild erythema, vaginal erosion, and edema. No patients dropped out of the study.

Anecdotal case series suggest that 5-FU might be useful for treatment of anogenital intraepithelial neoplasias in the general population, a claim that remains to be evaluated properly.153 In addition, 5% 5-FU cream, applied daily, has been used successfully in combination with 5% imiquimod cream three times a week for treatment of AIN grade 3 lesions in an HIV-positive man.154 Better evidence supports the use of 5-FU as secondary prophylaxis of CIN in HIV patients.155 In the ACTG 200 trial, 101 HIV-positive women who had undergone ablative or excisional treatment for CIN were randomized to receive either topical vaginal 5% 5-FU cream (2 g) self-administered twice a week or nothing. Of the 50 (28%) women in the 5-FU group, 14 developed CIN recurrences compared to 24 of 51 (47%) in the observation group (p < 0.05). Moreover, in the 5-FU group recurrences tended to appear later and were more likely to be CIN grade 1 than CIN grade 2 or 3.

Cidofovir (Vistide), or (S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)cytosine, is an acyclic nucleotide analog that is available for treatment of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis. Intralesional injection of the compound has been found effective in a small number of patients, HIV-infected or not, with cutaneous warts, condylomata acuminata, oral warts, recurrent respiratory papillomatosis, VIN, and upper digestive HPV tumors.156–165 A topical gel formulation of 1% cidofovir gel (Forvade) has been evaluated in a Phase II trial for treating condyloma acuminatum in immunocompetent patients.166 It was administered daily for 5 days every other week for up to six cycles. One-third of the patients were randomized to receive placebo. At the end of the treatment period (12 weeks), 9 of 19 (47%) patients treated with cidofovir had a complete response compared to none of 11 patients in the placebo group (P = 0.01). In an open, nonrandomized trial including HIV-infected patients, cidofovir (1% in Beeler base) led to a complete response rate of condylomata acuminata of 32% (9 of 27), compared to 100% (20 of 20) of those treated with electrocautery.167 Those patients failing cidofovir were given electrocautery. Relapse rate was low in this group (3.7%) compared to the group treated with electrocautery alone (55%).

Various strengths (0.3%, 1%, 3%) of cidofovir gel applied daily for 5 or 10 days every other week for up to three cycles were evaluated in an open Phase I/II study conducted in HIV-positive patients with anogenital warts.159 Overall, seven of 46 (15%) patients had a complete response. All treatment regimens appeared equipotent. Topical 1% cidofovir cream was compared to placebo in a small randomized study of condyloma acuminatum in HIV-infected patients.168 Partial clearance (>50% of wart area) was noted in half (three of six) of the cidofovir recipients, but in none of the six placebo recipients. Electrocautery was compared to 1% cidofovir gel (given daily 5 days a week, for up to 6 weeks) or 1% cidofovir gel (daily 5 days a week for 2 weeks) following electrocautery within 1 month for the treatment of condyloma acuminatum in HIV-infected patients.169 Electrosurgery alone achieved a 93% (27 of 29) complete response rate, compared to 76% (20 of 26) for cidofovir alone, and 100% (19 of 19) for the combined regimen. Cidofovir 1% gel was also administered three times every other day on biopsy-proven CIN grade 3 lesions in 15 immunocompetent women.170 One month later the cervix was excised, and seven of 15 (47%) of the specimens showed complete histologic resolution; four of them also demonstrated disappearance of HPV DNA. Topical cidofovir 1% has been associated with complete eradication of recurrent VIN grade 3 lesions in an HIV-negative woman. A 1% cream preparation was used to obtain the resolution of recalcitrant oral papillomatosis in an AIDS patient. Cidofovir gel or cream is currently not available commercially but can be made up by a pharmacist upon request.171 Cidofovir is a potential carcinogen, and caution should be exercised with its use.161

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy is one of the most common forms of treatment for anogenital HPV diseases and other dermatologic conditions. Solid carbon dioxide (carbonic ice; boiling temperature −78.5°C), nitrous oxide (−89.5°C), and especially liquid nitrogen (−196°C) are the principal cryogenic agents. Cold can be applied with cryogenic pencils or cotton swabs, but the most common modes of delivery are sprays for external lesions and cryoprobes of various sizes for internal lesions. Cryoprobes carry the potential risk of virus transmission, which is avoided with sprays.172 Cryotherapy techniques are varied and empiric.173–175 A common approach is to spray or cool the wart for 20 to 30 s until a 1–2 mm ice halo forms around the lesion. Some practitioners allow the lesion to thaw completely and then freeze it again.

Cold injury causes necrosis of the tissue but little HPV DNA destruction.117,176 The patient experiences a brief stinging sensation followed by numbness. Upon thawing, about half of the patients report discomfort: itching, burning, or pain.177,178 Uterine cramping follows cervical cryotherapy. Aggressive treatment may cause blisters and pronounced edema and should be avoided. One-fourth of the patients treated for condyloma acuminatum have skin discoloration at the treatment site 6 months later.177

The efficacy of cryotherapy for the treatment of condyloma acuminatum has been demonstrated in several open studies.128,129,179–188 Unfortunately, although it is a common approach, there have been few randomized comparative trials. This makes it difficult to define confidently the role of cryotherapy. Typically, 65–85% of patients have a complete response with a 20–40% recurrence rate. When recurrences are taken into account, the complete response rate with cryotherapy is ∼60%, which makes it a better choice than podophyllinand podofilox, equivalent to TCA, but slightly inferior to electrosurgery. Cryotherapy is particularly well suited for the care of meatal warts and the pregnant patient.

Along with electrosurgery and laser surgery, cryotherapy is used to treat internal HPV diseases (condylomas and intraepithelial neoplasias). These three techniques appear to have similar efficacies.189,190 Compared to laser therapy, cryotherapy of the cervix is more painful and associated with longer symptomatic bleeding and vaginal discharge.191 The cervix can be treated with cryotherapy during pregnancy.192

Cold-Blade Surgery

Surgical excision is one of the simplest radical approaches to the treatment of condyloma acuminatum. Thomson and Grace described the current technique developed for the treatment of anal warts.193 The skin is disinfected and the base of the lesion is infiltrated with an anesthetic such as lidocaine. The resultant swelling aids in demarcating the margins of the lesion. Epinephrine (1:100 000) may be added to the anesthetic to give better hemostatic control. The lesion is excised with curved (iridectomy) scissors, and bleeding is controlled by pressure with a gauze and application of 30% TCA or another hemostatic agent. The procedure is remarkably well tolerated. After the brief stinging pain of the anesthesia, little is felt by the patient, who later may experience mild local discomfort or itching. Frank pain is rare.194 Slight bleeding of the wound is often noted but is self-limited. Hypopigmentation, the most common long-term complication, occurs in a small number of patients, and hypertrophic scarring is rare.195 A variation of cold-blade surgery is the use of micro-resectors for internal lesions.196

Net complete response rates vary from 46% to 92% with cold-blade surgery.193,194,197–202 Typically, the procedure is reserved for patients with few lesions, and this potential selection bias may contribute to the excellent efficacy of this technique. Cold-blade surgery is often used in combination with other therapies such as podophyllin, fulguration (electrosurgery), or both, with no evidence that outcomes are improved. In HIV-seropositive patients, cold-blade surgery has been combined with fulguration for the treatment of anal condylomas. Results of these open, retrospective case series have been mixed. Beck et al found a recurrence rate of only 4% in 27 patients followed for a mean of 1 year.124 Miles et al treated 24 patients; of the 15 available for follow-up 1 month later, seven required additional treatment.203 The addition of systemic interferon-γ does not lower the recurrence rate.204 Wound healing after anorectal surgery for condylomata acuminata is usually not a problem in the HIV-seropositive patient, although it may be significantly delayed in the more severely immunocompromised patients (CD41 count >50 cells/μL) or those with anal cancer.205,206

Cold-blade surgery applied to the treatment of cervical HPV diseases is known as conization.207 It consists of excising a large cone of the cervix that includes the endocervix (the exocervix forms the base of the cone). Conization is now being largely replaced by less aggressive treatment options: electrosurgery, laser surgery, cryotherapy. Even for the rare indications of conization such as endocervical CIN or microinvasion, adapted laser and electrosurgical techniques (laser or loop electrosurgical excision cone biopsy) have replaced the traditional scalpel excision. As with all surgical procedures that generate biologic fluids potentially infected with HIV, the operator should wear gloves, apron or gown, mask, and eye protection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree