Introduction

Sexuality remains an important component of quality of life throughout the lifespan. Sexuality is much more than the physical act of sex and encompasses intimate feelings, sensuality and the way we view ourselves or others see us as men and women. Relationships are influenced by sexuality and cultural codes of behaviour set the boundaries of what is considered to be acceptable or unacceptable behaviours in given contexts such as a nursing home. Myths and prejudice abound in terms of societal and professional expectations about the sexual activity and behaviours of older people and their needs in this area can easily be over looked. Cultural norms and values are changing and it is likely that future generations of older people will be more assertive in terms of seeking health care advice and interventions. However, it is important to recognize that current prejudices and myths about celibacy dominate western views of sexuality and sexual activity in later life, and this may inhibit older people from seeking help with sexual performance, sexual health and relationships.

The spectrum of sexuality and ageing is outlined in Table 9.1. The full expression of sexuality is dependent on biological, psychological and social factors. Testosterone is a driver of sexuality in both sexes, but its effect is modulated by psychological and social factors. The effects of ageing on sexuality can create major anxiety but, with adequate education, sexuality can remain enjoyable throughout life. There is much misinformation about sexuality. Although open discussion of sexuality has become much more common in the last 40 years, many older persons come from a generation where sexuality remains a taboo subject. This chapter explores both the biology of sexuality and ageing, and also the emergence of the special needs of a substantial cohort of older gays and their unique needs. The role of disease in the sexuality of older persons is addressed and, finally, the problems faced by older persons who have had lifelong paraphilias are considered.

Table 9.1 Sexuality and ageing—the spectrum.

| Biological |

| Hypogonadism |

| Erectile dysfunction |

| Disease |

| Psychological |

| Depression |

| Sexuality attitudes |

| Perception of sexual attractiveness |

| Social |

| Social interactions |

| Partner availability |

| Physical fitness |

| Community education |

| Awareness of sexuality |

In the United States, a survey of males and females aged 57–85 years found that 73% of persons 57–64 years of age were sexually active.1 This prevalence declined to 26% of persons 75–85 years of age. Women at all ages were less sexually active than men. Sexual problems existed in half of the population but only 38% of men and 22% of women had discussed their sexual problems with a physician. Women reported a low desire (43%), poor vaginal lubrication (39%) and failure to climax (37%) as their main problems. About 37% of men had erectile dysfunction. Of these men, only 14% had used medications to improve their function. In a study of persons 75–85 years of age, 38.9% of men and 16.8% of women were sexually active.2 Good health was the major factor predicting a healthy sex life.

Sexual Health

It is essential that older people are informed and equipped to enjoy sexual activity safely. Older people are increasingly at risk at of sexually transmitted disease and they tend to delay seeking help longer than younger people from the onset of symptoms.3 Access to age-sensitive information and health promotion is important; sexually transmitted diseases are not a prerogative of the young. It is important for health professionals to recognize that many of the older people who consult with them today have not benefited from health education programmes and may be unaware of the protection provided by condoms.4

Sexuality and the Older Woman

Many women associate menstruation with femininity, fertility and youth, which is in sharp contrast to the symbolism of menopause, which signals biological ageing triggering a new dynamic in self identity and sexuality. In the medical literature, the view that menopause is a deficient state is prolific, which some would argue is a social construction of ageing based on the medicalization of menopause and failure to recognize this as a natural life transition.5 These debates aside, menopause is an individual experience derived from the interplay of physiological, psychological and other factors. Natural menopause occurs in women with an average age of 52 years. Epidemiological studies have suggested that the older a woman is at menopause, the longer she will survive following menopause. Smoking is a major cause of an early menopause.

Numerous studies of ageing and menopausal transition demonstrate multiple health-related changes, alterations to sexual response and impacts on intimate relationships that may lead a woman to seek support through either traditional or alternative medicine.6 The major symptoms of menopause are hot flushes and night sweats. These occur in approximately 85% of women at the time of menopause. Although in most women hot flushes last less than 5 years, a few women continue to have them into their 80s. Environmental factors such as spicy foods, alcohol, caffeine and hot weather and psychological factors, for example, stress, can be precipitants of hot flushes. Hormone replacement therapy is commonly prescribed to treat menopausal symptoms and to prevent post-menopausal bone loss. A concern of some women is that such treatment will result in weight gain; as shown by a recent systematic review of 28 randomized controlled trials with 28 559 women, there is no evidence of an effect of unopposed estrogen or combined estrogen with progestogen on body weight.7 It seems that body mass index increase is normal and associated with the onset of menopause that can be addressed by changes in life style, including diet and exercise. There is currently insufficient evidence to determine the role of exercise in the management of vasomotor menopausal symptoms.8 Menopause is not necessarily associated with a decline in libido. Some women find the cessation of menses liberating. Use of estrogen is declining following the results of the Women’s Health Initiative and the HERS study. These studies showed that both estrogen alone and estrogen plus progesterone were associated with an increase in myocardial infarction, stroke, pulmonary embolism and breast cancer.9, 10 This was balanced by a decrease in hip fracture and colon cancer. Unfortunately, estrogen also appears to accelerate the onset of cognitive impairment in older women.11

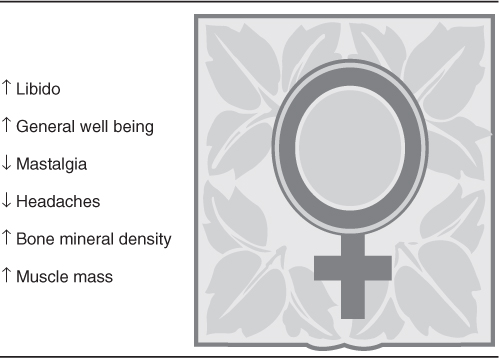

Testosterone levels decline rapidly between the ages of 20–40 years in women.12 There is then a slight increase in testosterone levels in women between the ages of 60 and 80 years. Testosterone, tibolone (an estrogen–progestagen–testosterone) and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) all improve libido in older women. In addition to increasing libido, testosterone has also been reported to improve general well-being, decrease mastalgia, decrease headaches and increase bone mineral density and muscle mass (Table 9.2). The testosterone products available for women are listed in Table 9.3. A number of studies have shown positive effects of testosterone patches in women with female sexual desire disorder.13

Table 9.2 Testosterone and women.

Table 9.3 Testosterone products available for older women.

| Testosterone |

| Compounded vaginal creams |

| Gels |

| Testosterone undecanoate |

| Estratest (estrogen plus methyltestosterone) |

| Tibolone |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone |

| Testosterone patch, testosterone pellets |

Female hypoactive sexual desire disorder is defined as persistently or recurrently deficient (or absent) sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity. This must cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty. The condition cannot be better ascribed to another psychiatric condition, for example, depression or to the effects of a substance, for example, medication or a general medical condition. The approach to the management of sexual dysfunction in older women is given in Table 9.4.

Table 9.4 Management of sexual dysfunction in older women.

| Listen/ask |

| Permission giving |

| Provide information |

| Specific suggestions |

| Vibrators |

| Paraclitoral stimulation |

| Lubricants |

| Sex therapy |

It is important to recognize that for many older women, intimacy and ‘cuddling’ are more important than intercourse. The sensitive clinician needs to recognize the specific needs of the individual and then work with her to obtain her goals. Some women will choose to use complementary therapies such as black cohosh or dong quai soy. It is important to recognize that there are no long-term data on their efficacy or safety. At present, the use of estrogen in women over 60 years of age should be avoided whenever possible. There is a clear need for increased research on sexuality in older women.

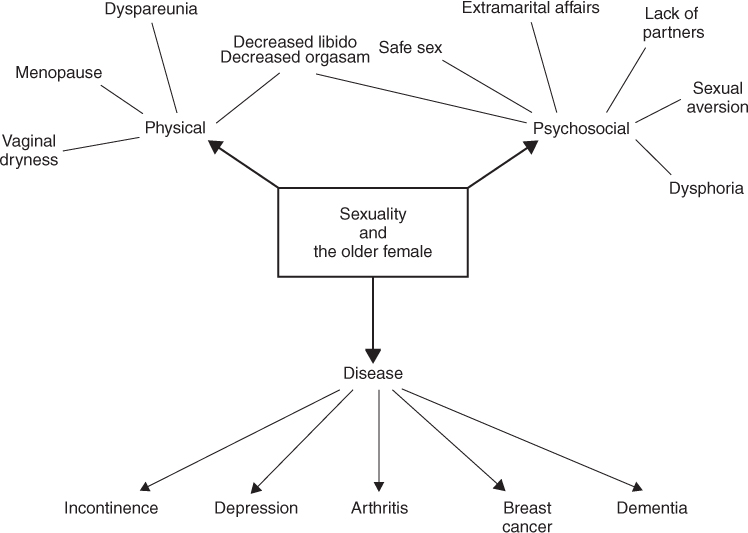

The major sexual problems reported by older women include lack of orgasm, lack of sexual interest, a decline in lubrication, failure to find an appropriate partner, dyspareunia, problems with safe sex and sexual intercourse decline from 30–78% at 60–70 years to 8–43% at 80 years. Most older persons who are still sexually active have intercourse an average of once per week. Approximately 45% of older women masturbate. Of those still having intercourse, 73% enjoy intercourse and the rest tolerate it. Only 21% of women over the age of 75 years still have a partner. Most studies have shown that the majority of physicians do not include sexual concerns and questions as part of their general history taking. Figure 9.1 provides the spectrum of sexuality and the older female.

A number of diseases have a major impact on sexuality in women. The disease that most alters a woman’s self- image is breast cancer. Up to 40% of women with breast cancer have a reduction in their sexual activity.14 The effect of breast cancer on sexuality is highly dependent on the relationship that the woman has with her partner. Urinary incontinence can modify sexual interactions in up to one-third of women. Severe incontinence may lead to the need for separate beds. Uterine prolapse is more likely than incontinence to alter sexual relationships. Urogenital atrophy, due to estrogen deficiency, leads to vaginal dryness, vaginal bleeding, urge incontinence, urinary frequency and dysuria, irritation and pruritus of the labia and mons, dyspareunia and urinary tract infections. All of these changes can lead to sexual dysfunction. A number of lubricants are now available to allow women to overcome vaginal dryness. Estrogen creams, tablets and rings may also be useful in the management of severe vaginal dryness. However, it must be remembered that vaginal estrogen is absorbed and may have all the effects of oral or parenteral estrogen.

Erectile Dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction is defined as the inability to attain or maintain a penile erection sufficient for sexual performance on at least two-thirds of occasions.15 Physiologically, older males have an increased time for development of erection and less full erections with a decreased pre-ejaculatory secretion. During orgasm, there is a decline in expulsive force and urethral contractions. Following ejaculation, there is a rapid tumescence with rapid testicular descent. The refractory period is markedly prolonged.

A number of older males have an active sex life.16 However, studies in Germany and South America has found that 53% of men aged 70–80 years have some degree of erectile dysfunction.17 The Massachusetts Male Aging Study showed that at 40 years of age, severe erectile dysfunction was present in 5.1% and moderate erectile dysfunction in 17%.18 By the age of 70 years, 15% had severe dysfunction and 34% moderate dysfunction. In the Olmsted County Study, 30% of men over 70 years of age had no erections and only 10% had intercourse more than once per week.19 The major risk factors for developing erectile dysfunction are heart disease, diabetes mellitus and hypertension.

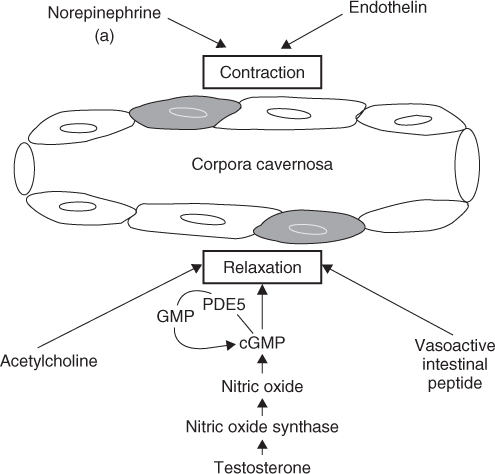

Erections occur when the smooth muscle of the corpora cavernosa relaxes, allowing pooling of blood. Figure 9.2 demonstrates the different neurotransmitters involved in producing penile erection.

Approximately half the males with erectile dysfunction are found to have vascular disease as a cause. Other causes include medications, psychogenic causes, neuropathy, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease and hyperprolactinaemia. Thiazide diuretics are the main medication-associated cause of erectile dysfunction worldwide. Tobacco use is associated with increased erectile function. In dogs, nicotine decreased cavernous nerve stimulation and increased erections. In humans, smoking two cigarettes decreases the quality of papaverine-induced erections.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree