html xmlns=”http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml”>

Chapter 5

Services for people with mild dementia

Introduction

Receiving a diagnosis of dementia is a highly significant event for the person with dementia and their family and loved ones. There is a significant stigma surrounding dementia, and many people still question the value of an early diagnosis given the paucity and limited effectiveness of current drug treatments, although many studies confirm that patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) do better if they are receiving specific drug treatment than those who are not.

The Dementia Action Alliance in England issued the National Dementia Declaration in October 2010 (http://wwww.dementiaaction.org.uk) for people with dementia:

- I have personal choice.

- I know services are designed for me.

- I have support that helps me live.

- I know how to get what I need.

- I find the environment enabling and supportive.

- I feel I belong and am valued.

- I know there is research which is going on which will bring me a better life.

The declaration stated that there should be good quality early diagnosis for everyone. This may be provided by rapid and competent specialist assessment, together with sensitive communication, treatment, care, support and capacity.

There have been significant advances in the way in which people with dementia are cared for. A growing body of experience, knowledge and awareness of the rights and needs of people with dementia has led to these advances. Nevertheless, there is still considerable variability not only across the different countries of the world but even within a given country. Such variability may depend on the nature of the medical system and the existence or not of a close-knit family structure: in some countries, most people with dementia remain within their family, whereas in others they are more likely to be managed within an institution, such as a nursing home. The greatest need is to ensure that there are locally appropriate services that deal with both the medical and non-medical aspects of AD and other types of dementia. A number of approaches appear to depend more on the enthusiasm of the therapists than the nature of the therapy, and such approaches are less clearly generalisable, even within the country where it has been developed.

The present chapter will describe some of the relevant service areas that are of particular importance to people with mild dementia at the time of, or soon after, they have been diagnosed. It will try and avoid discussing in detail areas such as management of behavioural issues that tend to be more of a problem in moderate or severe dementia and will therefore be covered in more detail in Chapters 6 and 7 in this book.

Dementia care is usually provided by a number of different agencies, and the UK is a good example of this. It involves the National Health Service and the social care system, together with privately funded services and those provided by voluntary organisations and family caregivers. The care may be provided in a range of different settings that will vary from one part of the country to another. Inevitably, there is a danger that such a system is too fragmented and people either do not get into the system to receive the appropriate help they and their families need or they may fall into gaps in the service. It is important, therefore, to try and ensure that the system of care being provided in a local area is integrated as far as possible, that the different parts of the system talk to each other and that there are easy cross-referral systems. Such complexity also makes it more difficult for a national or government policy to increase the quality of care through regulation: in the UK, the separation of health and social care has been a particularly divisive force. Increasingly, health and social care services are now seeking to work more closely together and to use coterminous boundaries for their area of activity, and this will undoubtedly improve the overall level of service provision.

Whilst national standards and inspection processes are necessary, it is also important to promote plurality of providers, to have adequate levels of flexibility in the system and to ensure that there is some choice for users.

The definition of mild dementia

In general clinical settings, the clinician’s main goal is to make a diagnosis of dementia and to try and define the subtype, most commonly AD. The severity of the dementia – mild, moderate, moderately severe or severe – is less commonly specified or formally assessed. Assessment of severity is usually only formally undertaken using standardised scales in research settings and in particular when considering patients for inclusion in clinical trials. In clinical settings, most often, cognitive function is used as the main marker of severity, supplemented by an impression of overall functioning as may emerge from taking the history, including corroborative history.

The Mini-Mental State Examination [1] remains the most widely used relatively short assessment of memory and cognition with a maximum score of 30. In an early comprehensive review [2], three levels of severity of cognitive impairment were suggested: 24–30 = no cognitive impairment; 18–23 = mild to moderate impairment, and 17 or below = severe impairment. However, intelligent patients may have a significant problem even though scoring 24 or above. In contrast, patients with marked language impairment or limited education may score poorly, suggesting that they are more severely affected than they are. In current clinical trials of potential drugs for mild AD, a MMSE cut-off of around 20 is increasingly selected as an inclusion criterion.

The severity of dementia has been most clearly characterised through two global rating scales that were originally developed in the 1980s. Such an assessment of global functioning allows a single subjective integrated judgement of the patient’s symptoms and performance by an experienced clinician. Although these have mainly been applied in research settings, the principle of an overall global assessment is in fact how every clinician ultimately makes a judgement about a patient’s level of dementia, and this cannot be done by the use of any single cognitive or other type of assessment. Although dementia does not necessarily progress in an orderly, linear way, these assessments are helpful in deciding whether a patient has mild, moderate or severe dementia.

The Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) was first described in 1982 [3]. Six domains are assessed: memory, orientation, judgement and problem-solving, community activities, home and hobbies, and personal care. It has a 5-point scale with 0 for no impairment, 0.5 for questionable or very mild dementia, and 1, 2, and 3 for mild, moderate and severe dementia, respectively. CDR-1 represents mild dementia where the person has moderate memory loss, especially for recent events and this interferes with daily activities. The person also has moderate difficulty solving problems, cannot function independently at community affairs, and has difficulty with daily activities and hobbies, especially complex ones. The CDR has become the most widely used global severity rating scale for clinical trials in AD, mainly because the scale was further developed within each domain [4].

The Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) was also described in 1982 and has equally stood the test of time [5]. It takes less time than the CDR to complete. It divides the disease into seven stages based on the amount of cognitive decline, where 1 = normal and 7 = very severe cognitive decline (late dementia). It is most useful for the assessment of AD because of the emphasis on memory. Stage 4 (the stage of moderate cognitive decline) equates to mild dementia. This stage includes difficulty with concentration and reduced memory for recent events. Travelling alone, especially in unfamiliar places, becomes more difficult as does handling money. Complex tasks are particularly problematic. Denial may become the subject’s main defence mechanism, and they may also begin to withdraw from family and friends because socialisation becomes more difficult.

The GDS has often been combined with the Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST), which looks more at the level of functioning and performance of activities of daily living than cognition [6]. Mild dementia is represented on the FAST both by stage 3 (early dementia with noticeable deficits in demanding situations) and stage 4 (mild dementia where the person requires assistance with complex tasks, such as finance or planning social occasions).

People with mild dementia will usually retain insight. Problems are more likely to occur with complex instrumental activities of daily living rather than with basic activities. They are also better placed than people with more advanced dementia to be actively involved in decisions that affect them and to understand and benefit from strategies for coping with memory and other cognitive problems.

Memory clinics and other specialist services for dementia diagnosis and assessment

Memory clinics

Specialist services for people with memory problems and mild dementia have a relatively short history and have tended to develop separately from other provisions for people with dementia, such as psychogeriatric services [7]. The memory clinic model began to develop in the USA in the mid-1970s to serve as an outpatient diagnostic, advice and treatment service for people with mild dementia. They began partly as a result of the frustration felt by the families of people with dementia because many physicians appeared to be reluctant to diagnose dementia, especially in those who appeared to have reasonable social skills and moderate everyday abilities. The term ‘memory clinic’ allowed the clinic to focus on memory-related problems, which were usually one of the first areas where problems were noted and avoided the term ‘dementia clinic’, which would potentially be unattractive and stigmatising [8]. The clinics were generally established by experienced and research-active specialists from a range of disciplines (particularly geriatric medicine, neurology and psychiatry) and allowed a focus on a group of disorders that had largely been ignored in terms of obtaining an accurate diagnosis and developing specific and effective management and treatment strategies.

In the 1980s and 1990s, there was a steady increase in the number of memory clinics in the USA, and they also developed in other countries, including in the UK, where the number increased from 20 in 1993 to 102 in 2002 [9,10]. The growth in memory clinics was apparently stimulated by the licensing of cholinesterase inhibitor drugs for AD and the development of services for early onset dementia. Most of the newer clinics had been set up within NHS old age psychiatry services and tended to be smaller and with less of an academic focus than the older clinics.

There is no precise definition of what constitutes a memory clinic and the speciality of the clinician leading the clinic varies both within countries and between countries. The early clinics in the UK usually had a strong research focus in contrast to the later clinics that developed following the licensing of cholinesterase inhibitors. The recent Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia has emphasised that consent to participate in research must again become a focus of attention, and this will be one of the conditions of accreditation for memory services [11]. Another feature that seems to be important is that the clinic should have a multi-disciplinary focus or, if not, provide ready access to other relevant specialties. A multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis of dementia has been shown to have more effect on the quality of life (QoL) of the patient and carer [12] and is also cost-effective in comparison with assessment as usual [13]. Other studies support the cost-effectiveness of memory clinics [14]. Referrals to memory clinics are usually from general practitioners, but some clinics also take self-referrals [15].

There is no doubt that memory clinics encourage earlier detection of dementia [16]. Patients, caregivers and general practitioners have positive opinions about the assessments, investigation and diagnosis, but improvements could focus on the clarity of diagnostic information and advice to relatives [16,17]. The benefits of memory clinics for post-diagnosis treatment and coordination of care are less clear cut. A 1-year study following diagnosis of dementia in nine Dutch memory clinics assigned patients post-diagnosis to either the memory clinic or the general practitioner. While quality of life of the patients was numerically higher and the caregiver burden lower in those followed up in the memory clinic, there were no significant differences between the two groups [18].

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has identified the key components of a memory assessment service to be the early identification and referral of people with a possible diagnosis of dementia and the development of a high-quality service for dementia assessment, diagnosis and management [19]. It includes recommendations from their Dementia Clinical Guideline [20] that memory assessment services should be the single point of referral for all people with a possible diagnosis of dementia and include a full range of assessment, diagnostic, therapeutic and rehabilitation services to accommodate the needs of people with different types and severities of dementia and the needs of their carers and families. It should also ensure an integrated approach with local healthcare, social care and voluntary organisations [20].

Other specialist services

Although many people with memory problems or dementia are now referred to memory assessment services, such patients will also present to specialists in routine outpatient clinics such as care of the elderly, neurology and psychiatry (particularly old age psychiatry). It is important that patients with mild dementia presenting in this way are given similar access to information, advice and treatment opportunities as those presenting to memory clinics. Referral on to the memory clinic or other services according to the local management pathway is recommended.

A comparison between patients referred to a memory clinic and those referred to traditional old age psychiatry services did demonstrate differences [21]. Memory clinic patients were significantly younger and had a wider range of diagnoses. Those diagnosed with dementia were found to be approximately 2 years earlier in the course of the disease compared with old age psychiatry patients. This does suggest that patients with mild dementia are more likely to be referred to a memory clinic.

The learning disability specialist services also have an important role to play. Learning disability (LD) is a term used almost exclusively in the UK to cover the ICD-10 categories for mental retardation (F70-79) in people of all ages. People with Down’s syndrome are at particular risk of developing AD and at an earlier age than the general population [22], while the prevalence of dementia in people with LD without Down’s syndrome is around two to three times that expected in people over 65 [23]. In this population, the diagnosis relies mainly on history and observation, as cognitive testing is more difficult and requires specific instruments [20]. It is more difficult to assess the severity of dementia in patients with LD where the dementia is often recognised as a change in behaviour rather than in cognition or function. Nevertheless, it is important for the specialist LD team to be aware of this and to offer advice (including potentially discussion of the diagnosis [20]) and help to the individual and their family and carers).

The role of primary care in diagnosis and assessment

There has been a widespread reticence among primary care doctors to make the diagnosis of dementia, and primary care diagnosis cannot be relied on according to a consultation exercise involving eight EU states (the Netherlands, Belgium, the UK, Spain, Italy, Portugal, France and Ireland) [24]. This generates a culture of ‘concealment, minimisation or ignoring of early signs and symptoms’. Yet diagnosis is the gateway to care [25]: without it, neither drug nor non-drug treatment can be given.

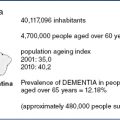

Diagnosing in primary care is perceived as a problem in many countries, resulting in delayed recognition and adverse outcomes for patients and their carers [26]. Improving early detection has been recognised as an area for development in the English National Dementia Strategy [27]; subsequent to this, there has been increasing discussion about whether primary care physicians (PCPs) can do more to diagnose people with dementia and, if so, what help can be provided to overcome some of the difficulties. Attempts have been made to educate and improve the abilities and confidence of people working within primary care in order to make adequate provision for people with dementia in their practice, but this has met with limited success [26]. From a primary care perspective, another problem is that the numbers seen by any one PCP are generally insufficient to provide the necessary experience and confidence in accurate diagnosis and management. In a demographically average area in the UK, the PCP might currently diagnose one to two patients per year and have 12–15 patients with dementia in a total list of 2000 patients [28].

One suggestion has been to modify the terminology and talk about ‘recognition’ rather than ‘diagnosis’ [26]. A two-step process has also been suggested, whereby the PCP detects cognitive impairment and loss of function, but the actual diagnosis and sub-typing is confirmed by a specialist [29]. This could potentially work well, but relies on good communication between the PCP and the specialist and easy access to the latter. It also relies on educational initiatives by local specialists to increase the confidence of PCPs and to ensure that they understand and accept the rationale for early diagnosis. Referral pathways may also be preferable to simple guidelines [26].

One attempt in Gnosall in the UK has been to develop a combined approach with the specialist team working within primary care and using the practice health visitor as the key liaison figure [30]. There is a monthly half-day session by a specialist old-age psychiatrist, with the availability of support and telephone expertise from a specialist between times.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree