html xmlns=”http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml”>

Chapter 4

Services for people with incipient dementia

Introduction

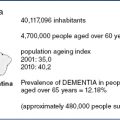

Deterioration of intellectual ability and psychosocial competence in late life that culminates in disability and dependence has become a paramount public health problem as a consequence of increased population longevity [1]. The most prevalent underlying brain pathologies are progressive neurodegenerative diseases; they often occur in combination with vascular changes [2,3]. Regarding clinical manifestations, initial asymptomatic stages are followed by subjective cognitive complaints [4], prodromal dementia, including mild cognitive impairment [5], and eventually by full-blown dementia. Increasing public concern about cognitive decline in old age and the prospect of treatments that delay neurodegeneration are driving the call for early diagnosis. In asymptomatic individuals with a family history of monogenic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or fronto-temporal dementia (FTD), an increased individual risk of developing dementia can be determined by predictive testing for known mutations many years or even decades before the onset of symptoms. In future, the feasibility of pre-clinical diagnosis may be enhanced by novel non-genetic laboratory or imaging techniques, which identify relevant features of ongoing neurodegeneration [6]. At the stage of prodromal dementia, when minor symptoms are present, evidence of the underlying brain pathology can be gained from combinations of neuropsychological tests, laboratory measurements and brain imaging [7]. In this chapter, the term ‘incipient dementia’ is meant to encompass both asymptomatic or pre-clinical and prodromal stages of the underlying brain pathology. Earlier diagnosis of dementia is associated with better opportunities for successful coping and disease management by patients, family carers and physicians, but also allows more time for people to deal with mental decline and progressive disability [8]. Therefore, once individuals have been assigned an increased risk of dementia, they should be offered counselling, as well as the best available preventative and therapeutic interventions. We discuss the needs of people with incipient dementia and the types of services that may be provided to meet these needs.

Needs of people with incipient dementia

Asymptomatic risk states

Two forms of asymptomatic risk states need to be distinguished because they differ with regard to frequency, diagnostic implications and practical consequences. The first refers to individuals who are genetically determined to develop dementia but have little brain pathology. In these rare cases, the family history and the demonstration of a deterministic gene mutation in a first-degree relative may initiate predictive genetic testing. Since known mutations for AD [9] and FTD [10] have an autosomal dominant mode of transmission and an almost complete penetrance, a positive test has not only implications for the tested individual, but also for their offspring.

A second form of pre-clinical risk states, which is much more frequent than the former, includes older adults where a progressive neurodegeneration is ongoing in the absence of deterministic mutations but still can be compensated for and therefore does not become manifest in overt symptoms. However, subtle decline in performance and increased effort associated with usual tasks may be recognised by affected individuals and may trigger the quest for diagnostic evaluation. These early stages of neurodegeneration cannot be identified by current diagnostic procedures. This may change, however, when refined laboratory tests and imaging methods that detect specific features of neurodegeneration, such as abnormal protein accumulation, aberrant enzyme activities or loss of neurons and synapses, become available [6]. Predictive genetic tests, as well as diagnostic procedures that identify pre-symptomatic stages of neurodegeneration, should be conducted in a setting of appropriate counselling and psychological support that covers the purpose of testing, the meaning of positive or negative results, the implications for the patient and their family, the financial and legal consequences, and the available options for prevention and treatment [11].

Prodromal dementia

Prodromal dementia often goes through the early clinical stage of subjective memory complaints without objective impairment to then move into a phase with emerging observable and measurable decline of functioning. This second phase would fall into the categories of ‘cognitive impairment, no dementia’ (CIND) or ‘mild cognitive impairment’ (MCI). The former represents a broad category that includes various underlying causes; the latter, especially the subform ‘amnestic MCI’, was originally used to describe individuals at increased risk to develop AD [12,13]. More recently, attempts have been made to identify the presence of AD pathology in such individuals, more specifically using biomarkers: in such cases, the term ‘prodromal AD’ is deemed more appropriate [14].

Neuropsychological testing in patients with MCI may not only reveal problems with memory, but also subtle impairment of executive function, information processing speed or visuospatial ability. Executive dysfunction is more closely associated with impairment of activities of daily living than with memory impairment [15]. Complex activities of daily living can be already impaired at the clinical stage of MCI [16,17]. Certain behavioural and psychological symptoms (BPS) are frequent, particularly depression, apathy, anxiety and irritability. These emotional changes are found in 1/3 to 2/3 of subjects [18–20]. Moreover, MCI can have adverse effects on social life in terms of isolation [21] or disruption of affectional expression and communication [22]. Because of its negative impact on cognitive functioning, practical skills, mood and interpersonal relationships, prodromal dementia is a significant threat to quality of life [23].

The prodromal phase of the behavioural variant of FTD typically presents initially with changes of personality and behaviour in areas such as motivation, emotional control, social awareness, behavioural inhibition and behavioural flexibility [24]. Language variants of FTD often show early reduction of verbal output, impaired naming and irregular word reading [25]. Neurocognitive test results regarding memory and executive functioning may not be specific at early stages of the disease. Prodromes of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease are less well studied. For emerging Parkinson’s disease dementia, executive dysfunction has been reported as an early clinical sign [26].

On clinical grounds and at cross-sectional examination, prodromal dementia may be indistinguishable from conditions of cognitive, functional and behavioural impairment, which are caused by non-progressive or reversible disorders. Therefore, the early diagnosis of a disease that will lead to dementia requires that evidence can be provided for the specific ongoing pathological process and for the deterioration from a previous level of memory, attention, executive function or visuospatial ability [7]. Established indicators for the pathology of AD include determination of amyloid β and tau proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET). These measures have been evaluated with regard to their potential for early diagnosis in several recent prospective studies, which involved participants with amnestic or amnestic multiple domain MCI and used progression to a clinical diagnosis of AD as outcome [27,28]. These investigations have shown that the neurobiological indicators for AD pathology achieve reasonable sensitivity, whereas specificity is low, and that combining indicators provides only minor gains in accuracy over using one single method. Importantly, the patient-relevant positive and negative predictive values of the neurobiological indicators (i.e. the probability of having the disease if the test is positive and the probability of not having the disease if the test is negative) [29] and hence the rate of false negative and false positive predictions in individuals with MCI are not satisfactory, even in a memory clinic setting where the prevalence of AD is high. Given the imprecision of current prognostic indicators, considering the dramatic consequences of the diagnosis for the individual and their families, and in view of the limited treatment options (see the next section), utmost caution should be exercised when establishing and disclosing the diagnosis of AD at the stage of MCI. In the case of diagnostic indicators showing abnormal values, it appears wise to emphasise diagnostic uncertainty and to conduct follow-up examinations in order to verify or exclude cognitive, functional or behavioural deterioration. For neurodegenerative disorders other than AD, no CSF or imaging diagnostic indicators are currently available for use in clinical practice [30,31].

Services for asymptomatic individuals at increased risk of dementia

Asymptomatic individuals with increased risk of developing dementia as determined by genetic tests or by early diagnostic indicators of neurodegeneration require interventions that prevent or delay the onset of symptoms, taking advantage of a long exposure time. Several strategies may be applied, aimed at modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and AD, including treatment of vascular risk factors, applying potentially neuroprotective agents, and strengthening brain reserve.

Medical treatment of vascular risk factors

Vascular risk factors, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperhomocysteinemia and diabetes, are among the most robustly established factors that predispose to cognitive decline and AD [32]. The potential of interventions that aim at preventing intellectual deterioration by modifying such factors in cognitively unaffected older individuals has been investigated in a number of prospective, randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Treatment of hypertension was evaluated in six trials, including individuals aged ≥ 60 years with normal cognition at baseline using stroke or coronary events as primary outcome and cognitive decline or incidence of dementia as secondary end points. Regarding reduction of cognitive decline, two studies were positive and two were negative. In terms of lowering the incidence of dementia one study was positive and one was negative. Thus, the evidence for prevention of cognitive decline or dementia by lowering blood pressure in late life remains inconclusive [33]. Interventions targeted at other vascular risk factors, including use of statins, lowering plasma homocysteine, managing diabetes mellitus, or combinations of pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies had no demonstrable impact on cognitive decline or on the incidence of dementia when used in older adults [34].

Neuroprotective agents

Supplementation of folic acid, vitamins B6 and B12 [35] or vitamins C and E and beta carotene [36] was compared with placebo in women aged ≥65 years with pre-existing cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular risk factors over more than 5 years. Neither regimen was associated with a lower rate of cognitive decline. Treatment with ginkgo biloba at a dose of 240 mg per day over 6 years had no impact on the rate of cognitive decline in cognitively healthy older individuals and did not reduce the incidence of dementia or AD [37]. Several other herbal preparations have interesting neuroprotective, antioxidant and anti-apoptotic properties, including cannabinoids, curcumin, resveratrol and ginsenosides [38]. However, no long-term trials have been conducted to determine the ability of such preparations to reduce cognitive decline in cognitively unaffected individuals.

Nutritional supplementation

The Mediterranean-type diet refers to an eating pattern which is rich in fish, vegetables, fruits, cereals and unsaturated fatty acids, but low in dairy products, meat and saturated fatty acids, and includes moderate use of red wine, usually with meals. Several prospective observational studies have examined the relationship between adherence to this nutritional style and cognitive decline, most of which were conducted on the same cohort of multiethnic Medicare beneficiaries in northern Manhattan. In the New York studies, higher adherence to a Mediterranean-type diet was associated with a lower risk of developing MCI during a mean follow-up period of 4–5 years in participants who were cognitively healthy at baseline [39]. In contrast, in a population-based study in France on cognitively healthy older adults, higher adherence to Mediterranean-type diet was associated with a slower decline on the Mini Mental State Examination within an average observation interval of 5 years but not on other cognitive tests. In that study, nutritional style was also not associated with the risk of incident dementia [40]. Thus, the evidence on the cognitive effects of the Mediterranean diet remains inconclusive. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, particularly eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), the principal natural source of which is fatty fish, have been assigned antioxidative, anti-inflammatory and membrane function-enhancing properties. Combinations of EPA and DHA were compared with placebo oil in two RCTs involving cognitively healthy elderly using cognitive performance as an outcome. In a Dutch study, which had a duration of 26 weeks, no effect on any cognitive domain was observed [41]. Likewise, in a longer-term study conducted in England and Wales over 2 years, no difference in cognitive function between active treatment and placebo was detected [42].

Strengthening brain reserve

Retrospective studies have consistently found an association between a cognitively enriched lifestyle and reduced risk of dementia [43]. It has been speculated that this relationship is mediated by compensatory mechanisms, including enhancement of structural or functional reserve [44]. Furthermore, several RCTs have demonstrated that cognitive exercise training can enhance cognitive abilities in healthy older adults [45–47] and may help maintain functional ability [48], although the specificity of training effects have been called into question [49]. However, no studies have been conducted to show that cognitive exercise can prevent or delay the onset of cognitive impairment in individuals at risk [50,51].

Physical activity

Regular physical activity is universally acknowledged as part of a healthy lifestyle at any age. Guidelines recommend at least 30 minutes of moderate physical activity on most days of the week. Epidemiological studies have consistently reported health benefits and reduced mortality [52]. Next to reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, there is also evidence that physical activity can contribute to reducing the risk of cerebrovascular disease [53–55]. A recent meta-analysis of RCTs of non-demented participants of various age groups with normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment or other medical conditions demonstrated that physical activity is associated with modest improvement in cognitive performance in the areas of attention, processing speed, executive function and memory [56]. While a number of longitudinal studies have provided evidence that regular physical activity is associated with a reduced risk for cognitive decline, dementia in general, vascular dementia and AD [40,57,58], no RCT has demonstrated yet that a physical activity intervention can reduce the incidence of dementia compared with a control group.

There are numerous hypotheses how physical activity could protect the ageing brain, including improved vascular health and cerebral blood flow, reduced impact of stress, inflammation and oxidation, enhancement of neurogenesis and synaptogenesis through factors, such as the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), with many derived from animal research, but increasingly also from trials with humans [59]. A recent RCT with 120 sedentary cognitively healthy older adults showed that 12 months of supervised aerobic exercise 3 days per week increased the volume of the hippocampus (measured with MRI) by 2% compared with a control group. The authors compare this 2% volume increase with reversing age-related loss of volume by 1–2 years [60]. There are ongoing discussions on which types of exercise, duration and intensity are the best for protecting brain health with currently support for aerobic exercise with a dose–response relationship [61]. Others point out that the biggest differences are found between sedentary people and those who do some physical activity [62], but more research is needed.

Services for people with prodromal dementia

Interventions for individuals with prodromal dementia have three major objectives:

A number of well-designed clinical trials have been conducted to explore the potential of cognition-focused interventions, psychotherapy, pharmacological treatments, medical foods, physical activity and assistive technologies for reaching these aims,

Cognitive interventions

Treatment strategies belonging to this group have been inconsistently labelled as cognitive stimulation, cognitive training or cognitive rehabilitation. Cognitive stimulation refers to activities aimed at general enhancement of cognitive and social functions. Cognitive training usually involves structured practice on tasks relevant to specific cognitive domains, such as memory, attention or executive function. Cognitive rehabilitation is an individualised approach focusing on the development of strategies to improve the management of day-to-day difficulties. During recent years, a few RCTs have evaluated cognitive interventions in people with MCI. In the majority of studies, moderate effects on memory performance and on global measures of cognitive ability were achieved. Computer-based exercises involving multiple cognitive domains had larger effects than unimodal memory training strategies. The latter may have limited effects and generalisability to overall cognitive functioning because they rely on the ability appropriately to apply newly acquired strategies. Moreover, high-volume exercises appear to result in greater benefit than lower amounts of training [63]. The clinical relevance of these findings has been questioned in several respects. The duration of effects is unknown since most trials were short and follow-up was lacking. Also, the specificity of effects is unclear because active control groups appear to do as well as those receiving training [49]. Furthermore, no convincing impact has been demonstrated for cognitive interventions on the ability of participants to carry out day-to-day tasks [64,65]. No long-term studies have been conducted to date to demonstrate whether cognitive interventions can slow cognitive decline and delay the onset of dementia in people with MCI.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree