SEMINOMATOUS AND NONSEMINOMATOUS GERM-CELL TUMORS

Part of “CHAPTER 122 – TESTICULAR TUMORS“

SYMPTOMATOLOGY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The usual presentation of testicular cancer is a painless mass, but pain occurs in 15% to 35% of the cases.72 A scrotal mass can be caused by several nonmalignant conditions, such as epididymitis, orchitis, inguinal hernia, hydrocele, varicocele, and spermatocele, and a correct initial diagnosis of testicular cancer is made in only 55% to 60% of the cases.73 The most frequent erroneous diagnosis is urogenital infection, especially epididymitis. Ultrasonography can improve the diagnostic differentiation between scrotal abnormalities. This procedure is particularly useful when the tumor is small and centrally located. If a tumor cannot be ruled out, surgical exploration through an inguinal incision should be done. A biopsy is insufficient.

In 5% to 10% of the cases, the presenting symptoms or physical signs of testicular cancer are secondary to metastatic disease.74 Symptoms such as pain in the lumbar region and uncharacteristic discomfort can be caused by retroperitoneal metastases. Pulmonary symptoms attributable to metastases are rare and generally related to massive pulmonary infiltration.

Although effective therapy is available for testicular cancer, it is important to diagnose these tumors as early as possible. The presence of a scrotal mass always should raise the suspicion of a germ-cell tumor. Furthermore, signs and symptoms such as gynecomastia (see Fig. 122-1A), lumbar pain, or a retroperitoneal, mediastinal, pulmonary (see Fig. 122-1B), or left supraclavicular tumor in a young male always should lead to a thorough investigation for a germ-cell tumor. The evaluation includes careful examination of the testes, ultrasound, and measurements of serum tumor markers. Germ-cell tumors in the testis can be present without physical signs. Furthermore, germ-cell tumors may originate in extragonadal structures. Delays by patients and by physicians often amount to several months and adversely affect the prognosis.73,75

BIOCHEMICAL MARKERS IN SERUM (“TUMOR MARKERS”)

Sixty percent of nonseminomatous germ-cell tumors produce AFP, hCG, or both. Although some seminomas excrete small amounts of hCG, large amounts of hCG or AFP in the serum generally indicate the presence of a nonseminomatous germ-cell tumor. Smaller increases in serum AFP (<200 μg/L) are found in some patients with benign liver diseases. Higher levels can be seen in hepatomas (sometimes on the order of grams per liter). If the level in serum exceeds 200 to 300 μg/L, the AFP of germ-cell origin can be distinguished from that of hepatic origin by lectin-affinity immunoelectrophoresis.76 Certain tumors of non–germ-cell origin (e.g., large cell carcinoma of the lung) can produce hCG, although usually in relatively small amounts.

The proportion of patients with tumors who have markers in the serum increases with advancing stage of disease. The half-life of tumor markers in the serum is ˜1 day for hCG and 5 days for AFP. Therefore, if tumor markers do not disappear within days (hCG) or weeks (AFP) after the removal of the testicular lesion, residual tumor tissue must be present. Thus, the measurement of tumor markers during and after treatment is a valuable tool for the detection of residual or relapsing tumor. New markers, especially for seminomas and embryonal carcinomas, are needed. TRA-1-60 is of interest, although its value remains to be confirmed.77

STAGING

Careful staging is always mandatory in testicular cancer, primarily because the treatment strategy and prognosis depend on the extent of disease.78,79 Noninvasive procedures include roentgenography of the thorax, and computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography, or both, of the retroperitoneal area. The evaluation also should include the measurement of serum tumor markers.

When metastases are present, the retroperitoneal lymph nodes are involved in 85% of the cases. Therefore, study of these lymph nodes is essential, and CT scan or ultrasonography always should be done. Positron emission tomography scanning is being performed, especially for visualization of retroperitoneal metastases.80 This procedure is likely to lead to better detection of small metastases.

Until recently, it was common practice to carry out a staging laparotomy in patients with nonseminomatous tumors. In many medical centers, this procedure has been replaced by a “wait and see” policy. By performing a thorough retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, ˜20% of patients thought to be without extragonadal disease are found to have micrometastases in the lymph nodes.

Conventional chest films usually are sufficient to identify pulmonary metastases; however, metastatic involvement of mediastinal lymph nodes can be difficult to visualize. Therefore, a CT scan of the thorax should be a part of the staging procedure.

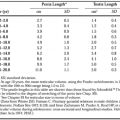

On the basis of the results of the staging procedure, the disease can be classified into stages: stage I (no metastases), stage IIA (retroperitoneal node metastases <2 cm), stage IIB (retroperitoneal node metastases ≤5 cm), stage IIC (retroperitoneal node metastases >5 cm), stage IIIA (supradiaphragmatic node metastases), or stage IIIB (extranodal metastases; e.g., lung).78,79

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

The primary treatment of testicular cancer is orchiectomy. In the rare cases in which systemic treatment is begun without orchiectomy, this operative procedure should be carried out subsequently.

Treatment after orchiectomy differs according to the type of testicular tumor (i.e., seminoma vs. nonseminoma) and the stage of disease. A few decades ago, surgery and radiotherapy were the only effective therapies for testicular cancer. The prognosis for patients with nonseminomatous testicular cancer was poor; most eventually died of their disease. With the advent of modern systemic treatment and with the optimal use of combined modalities, the outlook for patients with testicular cancer has improved dramatically: More than 90% can be cured by appropriate treatment.

Germ-cell tumors are among the most sensitive of the malignant diseases to cytotoxic drugs. Active single agents include cisplatin, vinblastine, bleomycin, etoposide, ifosfamide, dactinomycin, methotrexate, and mithramycin. However, cures seldom are achieved with single-agent chemotherapy; to obtain long-term survival, combination chemotherapy should be used. A combination of cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin is recommended as standard treatment,81 but other cisplatin-based combinations also can be used.

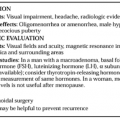

SEMINOMA

Seminomas are highly radiosensitive.82 The standard treatment of patients with stage I disease includes irradiation of the retroperitoneal, ipsilateral pelvic, and inguinal lymph nodes. Usually, a dose of 25 to 35 Gy is sufficient. More recent studies indicate that 25 Gy is sufficient and that paraaortic irradiation is adequate.83 The basis for this treatment is the assumption that micrometastases are present in many cases, although the actual incidence is unknown. The long-term survival rate with this treatment strategy is >98%.84,85 A surveillance strategy is used for patients with stage I disease, based on the assumptions that more than 70% of these patients would be cured by orchiec-tomy and that “relapses” can be cured.86 This strategy has yielded good results, but still should be considered experimental (i.e., restricted to clinical trials). In stage II seminomas, the radiotherapy is directed to the same area. In the final part of this treatment, a boost of 5 to 10 Gy is delivered to the retroperitoneal tumor area. However, ˜30% of patients with a retroperitoneal tumor diameter exceeding 5 cm cannot be cured by radiotherapy alone, and many centers recommend chemotherapy as a primary treatment in these cases. Others still prefer to give radiotherapy initially.87 With either strategy, long-term survival for patients with stage II seminoma exceeds 90%.85

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree