Screening and Surveillance for Prevention of Colorectal Carcinoma

Felice Schnoll-Sussman

Amir Soumekh

Colorectal carcinoma is the most common malignancy of the gastrointestinal tract and the second most common cause of cancer-related death in the United States. Most tumors are preceded by preexisting adenomas, although some develop from nondysplastic serrated polyps, and others arise in the setting of inflammatory bowel disease. Identification and removal of these cancer precursors is a primary goal of gastroenterologists performing screening colonoscopies. Colonic polyps are also routinely encountered during colonoscopies or sigmoidoscopies performed for other indications. Upon identifying and removing a premalignant polyp, clinicians need to provide patients with prognostic information, a plan for colonic surveillance following the initial procedure, and identify patients whose polyps represent a manifestation of a familial cancer syndrome. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss current practice guidelines regarding screening and surveillance of patients with colorectal polyps at risk for cancer development. Surveillance of patients with inflammatory bowel disease is discussed in Chapters 4 and 15.

ADENOMATOUS POLYPS

The vast majority of colonic cancers arise from adenomatous polyps. Their development is influenced by age, gender, and other risk factors such as body mass index, level of physical activity, and possibly race. Approximately 25% of asymptomatic patients have adenomas at the time of screening colonoscopy, although their prevalence ranges from 2% in patients in their 20s or 30s to 50% by age 70.1,2 Adenomas occur more commonly among males than females: Men have up to 15% more polyps than women. Adenomas are also associated with abdominal obesity and lack of physical activity.3, 4 and 5 Frank adenocarcinoma and larger adenomas are more prevalent among African Americans for unclear reasons; differences between races may reflect variation in location and polyp type or differences in screening rates between Caucasians and African Americans.6,7

Adenomatous polyps are endoscopically categorized by size and morphology. Polyps are classified as diminutive (<5 mm diameter), small (5 to 10 mm diameter), or large (>1 cm diameter). Adenoma size increases with age, and larger polyps are seen more frequently in the distal colon.1 Diminutive polyps are commonly encountered in routine colonoscopic examinations and up to 50% are adenomatous, although less than 5% show high-grade dysplasia or contain villous elements and only 0.1% contain invasive adenocarcinoma.8,9 It is not clear whether these polyps have potential to grow substantially over time or if endoscopic resection improves outcome.10, 11 and 12 Emerging data suggest that diminutive polyps can be resected and discarded without pathologic examination, thereby saving health care costs without significantly impacting clinical care.13 Nonetheless, current screening guidelines do not distinguish between diminutive adenomatous polyps and those that span 5 to 10 mm. Large polyps are considered to represent advanced adenomas regardless of their pathologic features because they are more likely to have high-risk features, such as a villous architecture, high-grade dysplasia, or even carcinoma, the latter of which may be present in nearly half of these lesions.14 Thus, current surveillance guidelines require a shorter duration of surveillance for patients with large adenomas.

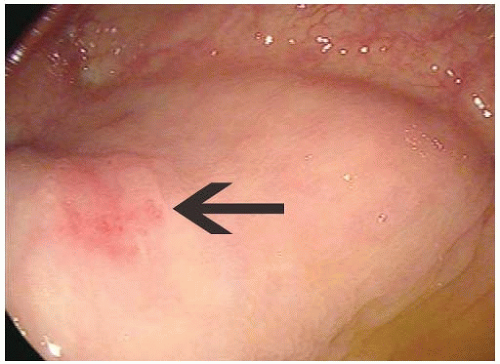

FIGURE 3.1: Flat polyps have a height one-half that of their diameter. They may appear as an erythematous area (arrow) and are difficult to detect during routine colonoscopic examination. |

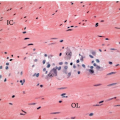

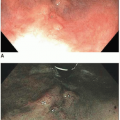

Colorectal polyps are classified as sessile, pedunculated, or flat based on their endoscopic appearances. Sessile adenomas are broad-based lesions, whereas pedunculated lesions have a slender fibromuscular stalk connecting the polyp to the colonic wall. There is no clear biologic difference between sessile and pedunculated polyps. However, sessile polyps may require piecemeal removal due to difficulties achieving endoscopic excision, in which case they require follow-up evaluation at very short intervals (2 to 6 months) to confirm complete removal.15 Flat adenomas have a height that is less than one-half the overall diameter (Figure 3.1). Though less common than raised lesions, flat adenomas are difficult to detect and may behave more aggressively. Flat polyps account for approximately 10% of all adenomas detected by routine colonoscopy compared to 36% of polyps found during colonoscopies enhanced by chromoendoscopy, suggesting that many flat lesions are missed during routine colonoscopy.16 Flat lesions with central depressions are highly likely to contain invasive adenocarcinoma.17

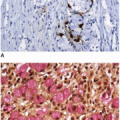

Adenomatous polyps are subdivided into three major types based on the predominant glandular architecture. More than 80% of adenomatous polyps display a tubular growth pattern, whereas tubulovillous and villous adenomas account for the remainder and occur in near equal numbers.18, 19 and 20 Tubular, tubulovillous, and villous adenomas vary with respect to their risk for high-grade dysplasia and cancer, and thus, pathologic classification of adenomas affects postpol-ypectomy surveillance intervals. Adenomas with villous features are more likely to contain high-grade dysplasia and have increased risk of carcinoma. For this reason, they require surveillance at shorter intervals than tubular adenomas (Table 3.1).21,22

SERRATED POLYPS

Serrated polyps comprise a heterogeneous group of nondysplastic and dysplastic polyps with serrated glandular architecture and include hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated polyps (sessile serrated adenoma), and (traditional) serrated adenomas, as described in Chapter 4. Of these, hyperplastic polyps are most common. They are detected in approximately 10% of routine screening colonoscopies performed among asymptomatic patients over the age of 50 and autopsy data report an overall prevalence of 20% to 35%.1,23 Sporadic hyperplastic polyps have little, or no, intrinsic malignant potential, and thus, patients with hyperplastic polyps of the distal colon are considered to have normal colonoscopies.22,24 However, detection of distal hyperplastic polyps during screening sigmoidoscopy may warrant follow-up full colonoscopy since up to 25% of patients with hyperplastic polyps have adenomas in the abdominal colon and 5% have advanced adenomas of the proximal colon.25 Serrated adenomas comprise approximately 2% of all serrated polyps, are frequently pedunculated, and show a predilection for the left colon.26,27 Sessile serrated

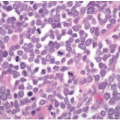

polyps occur more commonly in the proximal colon and are often missed during colonoscopy, with a wide variability in their detection rate among endoscopists.28 This high miss rate is at least partially due to their morphology; sessile serrated polyps are often flat, making them difficult to identify in patients with a poor bowel cleansing preparation (Figure 3.2).29 Sessile serrated polyps may harbor advanced neoplasia, and large polyps (≥1 cm) have been implicated as potential risk factors for development of colorectal cancer.30, 31 and 32 Management of serrated polyps is controversial, although some guidelines recommend that these lesions be managed comparably to adenomatous polyps of similar size.22,33,34

polyps occur more commonly in the proximal colon and are often missed during colonoscopy, with a wide variability in their detection rate among endoscopists.28 This high miss rate is at least partially due to their morphology; sessile serrated polyps are often flat, making them difficult to identify in patients with a poor bowel cleansing preparation (Figure 3.2).29 Sessile serrated polyps may harbor advanced neoplasia, and large polyps (≥1 cm) have been implicated as potential risk factors for development of colorectal cancer.30, 31 and 32 Management of serrated polyps is controversial, although some guidelines recommend that these lesions be managed comparably to adenomatous polyps of similar size.22,33,34

Table 3.1 Surveillance Guidelines for Colon Cancer according to the United States Preventive Services Task Force and Multisociety Task Force for Colorectal Cancer | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||