Pathologic Staging Issues: Implementation of the TNM Staging System

Rhonda K. Yantiss

Tumor stage is the single most powerful predictor of outcome among colorectal cancer patients and is determined by assessment of three parameters: local extent of the primary tumor, regional lymph node metastases, and distant metastases.1 The TNM (tumor, lymph nodes, metastasis) staging system for colorectal carcinoma is endorsed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and Union for International Cancer Control and routinely used in the United States and Europe.2 Unlike prior staging systems, this classification scheme provides pathologists, clinicians, and radiologists with a common language for uniform reporting of cancer stage and is continually updated as new elements prove to be of prognostic and/or therapeutic importance. Recent changes to pathologic stage assessment of colorectal carcinoma have been incorporated into the AJCC/TNM seventh edition Cancer Staging Manual and embraced by the College of American Pathologists (CAP), although definitional criteria for many elements are poorly reproducible and pathologists apply them in inconsistently.3 The purpose of this chapter is to discuss some of the diagnostic problems encountered when applying staging criteria enumerated in the AJCC/TNM seventh edition Cancer Staging Manual to surgical pathology specimens.

TNM DESCRIPTORS

Patients with colorectal carcinoma routinely undergo clinical staging prior to definitive surgical therapy. Clinical stage assignment is based on a combination of parameters including physical examination, endoscopic findings, and results of imaging studies. The clinical classification (cTNM) may differ from the final pathologic classification (pTNM) due to a variety of factors. Clinical stage is higher among patients in whom complete pathologic classification is not possible, such as individuals who have nonsurgical metastatic disease. Patients who receive neoadjuvant therapy for advanced cancers are assigned a clinical stage prior to initiation of treatment that is generally higher than the pathologic stage, which is assigned following surgical resection of a cancer that frequently shows some degree of regression. Alternatively, some patients are assigned a higher pathologic than clinical stage because their resection specimens contain more extensive disease than is clinically suspected prior to surgery. In these situations, the highest stage classification is used for final stage grouping.

The TNM stage assignment is subject to additional prefixes and suffixes in special situations. Stage is qualified by a “y” prefix (ypTNM) to denote cases in which classification is performed following neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both. This is particularly common among individuals with rectal tumors because most patients with advanced rectal cancer receive some form of therapy prior to definitive surgical resection. The “r” prefix (rpTNM) is used less frequently but identifies tumors that recur following a disease-free interval. Recurrent carcinomas that develop at a surgical anastomosis are, by convention, assigned to the proximal colonic segment and restaged. If the proximal segment is the small intestine, then the tumor is designated

based upon the colonic or rectal portion of the anastomosis, as appropriate. Cancers that are classified at the time of autopsy are denoted with an “a” prefix (apTNM). The “m” suffix indicates the presence of multiple primary tumors at a single site (pTmNM). Pathologic stage is assigned based on extent of the most advanced carcinoma when multiple tumors are present.

based upon the colonic or rectal portion of the anastomosis, as appropriate. Cancers that are classified at the time of autopsy are denoted with an “a” prefix (apTNM). The “m” suffix indicates the presence of multiple primary tumors at a single site (pTmNM). Pathologic stage is assigned based on extent of the most advanced carcinoma when multiple tumors are present.

LOCAL EXTENT OF DISEASE (TUMOR STAGE)

The designation for pathologic tumor stage (pT) describes the deepest point of tumor penetration in the colonic wall. Colorectal epithelial neoplasms are assigned pathologic stages pTis, pT1, pT2, pT3, and pT4, as described below.

Tumor Limited to the Muscularis Mucosae (pTis)

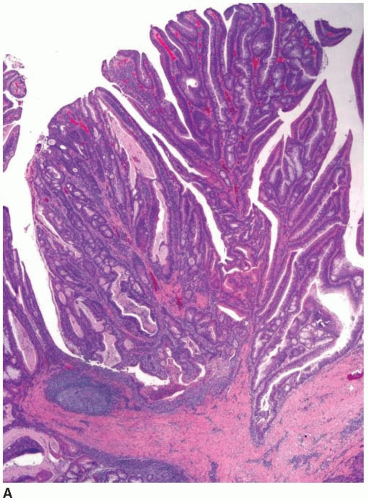

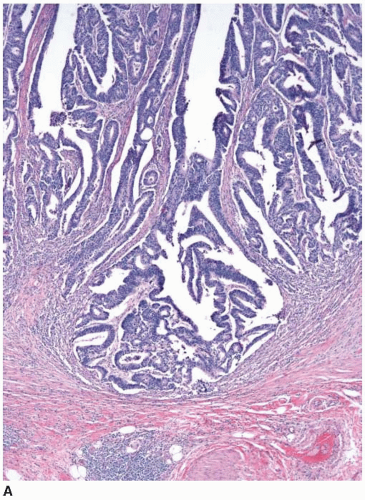

Cytologically malignant epithelial cell proliferations that are limited to the colorectal mucosa are classified as carcinomas in situ and assigned the pTis designation. However, both “carcinoma in situ” and pTis are generally avoided in routine practice because these terms apply to two different situations, are potentially confusing to treating clinicians, and may result in overly aggressive management. The pTis grouping includes intraepithelial carcinoma, as defined by an architecturally complex proliferation of neoplastic epithelial cells with malignant cytologic features (e.g., loss of polarization, nucleomegaly, macronucleoli, cellular necrosis, typical and atypical mitotic figures) that does not transgress the basement membrane (Figure 8.1). Carcinoma in situ (pTis) is also used to describe intramucosal carcinomas that breach the basement membrane

and extend into the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae but do not invade the submucosa (Figure 8.2A). Intramucosal carcinomas consist of irregular clusters and nests of tumor cells that do not evoke a desmoplastic stromal response (Figure 8.2B). Neither intraepithelial nor intramucosal carcinoma has potential to metastasize, yet some clinicians may be alarmed by usage of the “carcinoma” terminology and be tempted to treat such lesions aggressively. For this reason, the World Health Organization has proposed alternative terms “intraepithelial neoplasia” and “intramucosal neoplasia” to denote intraepithelial and intramucosal carcinoma, respectively.4 This suggestion has met with limited success. “Intraepithelial neoplasia” and “intramucosal neoplasia” are not commonly used as diagnostic terms in the United States. “High-grade dysplasia” is a more widely accepted term than either “intraepithelial carcinoma” or “intraepithelial neoplasia,” and “intramucosal carcinoma” seems to be preferred over “intramucosal neoplasia.”

and extend into the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae but do not invade the submucosa (Figure 8.2A). Intramucosal carcinomas consist of irregular clusters and nests of tumor cells that do not evoke a desmoplastic stromal response (Figure 8.2B). Neither intraepithelial nor intramucosal carcinoma has potential to metastasize, yet some clinicians may be alarmed by usage of the “carcinoma” terminology and be tempted to treat such lesions aggressively. For this reason, the World Health Organization has proposed alternative terms “intraepithelial neoplasia” and “intramucosal neoplasia” to denote intraepithelial and intramucosal carcinoma, respectively.4 This suggestion has met with limited success. “Intraepithelial neoplasia” and “intramucosal neoplasia” are not commonly used as diagnostic terms in the United States. “High-grade dysplasia” is a more widely accepted term than either “intraepithelial carcinoma” or “intraepithelial neoplasia,” and “intramucosal carcinoma” seems to be preferred over “intramucosal neoplasia.”

Tumor Invasive of, but Limited to, the Submucosa (pT1)

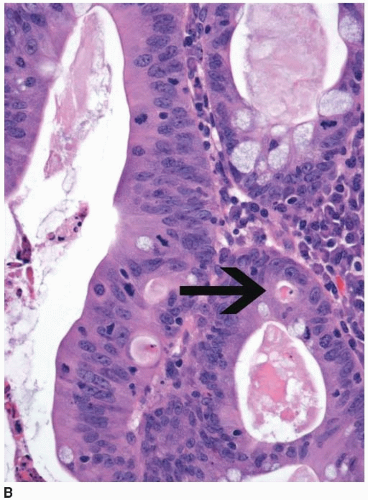

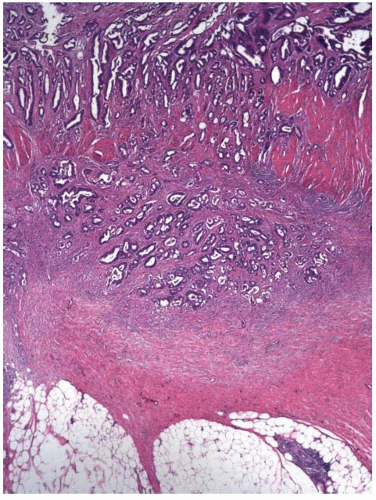

Most invasive colorectal adenocarcinomas limited to the submucosa (pT1) are detected in polypectomy specimens since these tumors are typically asymptomatic and identified during screening or surveillance colonoscopy. Invasive adenocarcinomas grow in an expansile, infiltrative pattern and are not accompanied by lamina propria tissue (Figure 8.3A). Invasion of the submucosa incites a desmoplastic stromal response in close proximity to malignant-appearing epithelial cells that display nuclear pleomorphism, nuclear membrane irregularities, and clumped chromatin (Figure 8.3B). Prior studies have shown that carcinomas arising in pedunculated adenomas may be adequately treated with polypectomy alone, provided the invasive carcinoma is low grade, lacks vascular invasion, and is

present at least 1 mm from the cauterized base of the polyp.5, 6 and 7 At a minimum, these three criteria should be incorporated in the final pathology report for all carcinomas present in polypectomy specimens. Other key components of the pathology report include anatomic location of the tumor, tumor size (invasive component), tumor budding, and distance of the tumor to the resection margin.

present at least 1 mm from the cauterized base of the polyp.5, 6 and 7 At a minimum, these three criteria should be incorporated in the final pathology report for all carcinomas present in polypectomy specimens. Other key components of the pathology report include anatomic location of the tumor, tumor size (invasive component), tumor budding, and distance of the tumor to the resection margin.

Tumor Invasive of, but Limited to, the Muscularis Propria (pT2)

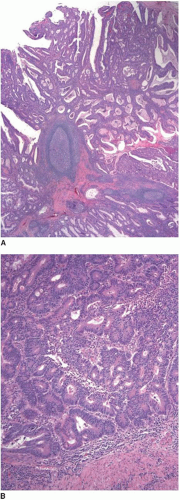

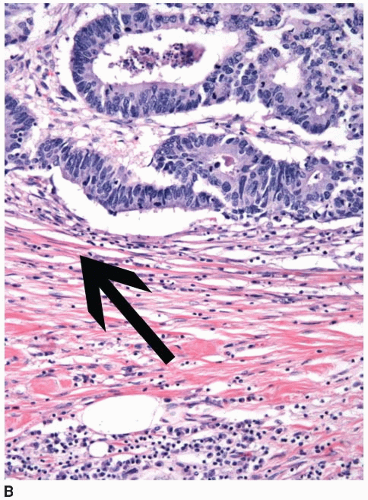

Colorectal carcinomas that invade into, but are limited to, the muscularis propria are assigned a pT2 pathologic stage, even if they are separated from the pericolic fat by as little as a single layer of smooth muscle cells (Figure 8.4). Recognition of muscularis propria invasion is generally straightforward, although problems may arise when assessing tumors that develop in colonic segments affected by diverticulosis. In this situation, herniations of mucosa through the colonic wall can be colonized by cancer cells (pT1) and simulate the appearance of a more advanced tumor in the muscularis propria or pericolic fat.

Tumor Invasive of Pericolic or Perirectal Soft Tissue (pT3)

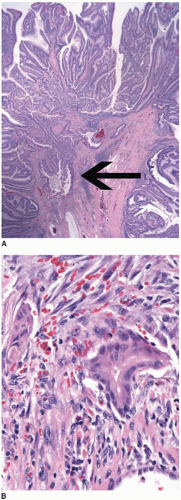

The absence of muscularis propria smooth muscle cells between the leading edge of the tumor and the pericolic fat represents the minimum criterion for pT3 classification (Figure 8.5). Some investigators suggest that cancers in the pericolic fat should be subclassified based upon their depth of invasion beyond the muscularis propria. Proposed schemes separate carcinomas invasive of pericolorectal soft tissue into four categories: pT3a (<1 mm beyond muscularis propria), pT3b (1 to 5 mm beyond muscularis propria), pT3c (>5 to 15 mm beyond muscularis propria), and pT3d (>15 mm beyond muscularis propria).8 Although the AJCC/TNM seventh edition Cancer Staging Manual does not subdivide the pT3 category, tumors that extend less than 5 mm beyond

the muscularis propria are associated with a better prognosis than those that penetrate more deeply into the pericolic fat.9 Thus, pathologists should assess extent of tumor beyond the muscularis propria and incorporate depth of invasion into the pathology report if possible.

the muscularis propria are associated with a better prognosis than those that penetrate more deeply into the pericolic fat.9 Thus, pathologists should assess extent of tumor beyond the muscularis propria and incorporate depth of invasion into the pathology report if possible.

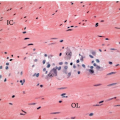

FIGURE 8.4: (Continued) Carcinomas limited by a single layer of smooth muscle cells (arrow) are still staged in this category (B). |

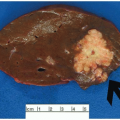

Tumor Penetrates the Peritoneum (pT4a) or Directly Invades Adjacent, Noncontiguous Structures (pT4b)

The most problematic aspect of pathologic tumor stage assignment is recognition of pT4 lesions. This group is subdivided in two categories: pT4a is defined as serosal penetration, whereas pT4b is defined as tumor that directly invades, or is adherent to, other organs or structures. The definitions for pT4a and pT4b in the AJCC/TNM seventh edition Cancer Staging Manual

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree