CHAPTER 39 Schistosomiasis

Epidemiology

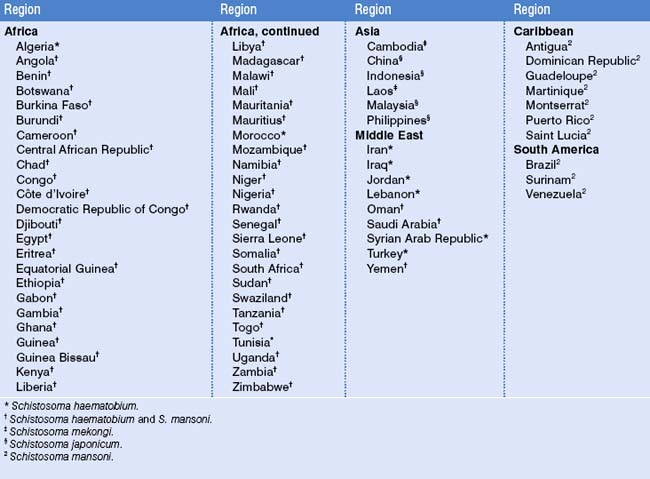

Worldwide, 500–700 million people are at risk for acquiring schistosomiasis, and 200 million people throughout Africa and parts of South America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia are infected (Table 39.1).5–8 The parasite is found in tropical regions in fresh water harboring competent snail vectors.9 The snail vectors are Schistosoma speciesspecific. For Schistosoma mansoni, competent snail vectors are in the genus Biomphalaria (Africa, much of the Arabian Peninsula, Brazil, Surinam, Venezuela, and some Caribbean islands); for S. haematobium, it is Bulinus africanus (sub-Saharan Africa, West Africa), tetrapoloid members of B. tropicus/truncates complex (Mediterranean region, Southwest Asia, and West Africa), and B. forskalii group (Arabia, Mauritius, and West Africa); for S. japonicum, Oncomelania hupensis is the vector in China, Indonesia, and the Philippines. S. mekongi is transmitted along the Mekong River in Cambodia and Laos by Neotricula aperta.5 Movements of infected human populations and large-scale irrigation projects, which extend the range of competent snail vectors, have expanded endemic areas.5,10 Within heavily endemic areas, prevalence rates may exceed 50%. However, high prevalence rates are not confined to native populations, as expatriate communities within endemic areas are also reported to have high prevalence rates.11

Etiology

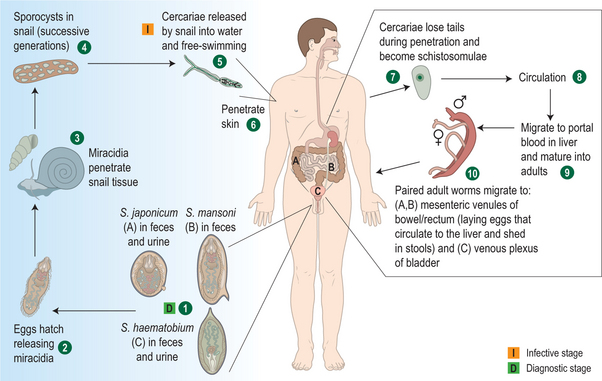

Schistosomiasis is caused by trematode parasites.6 Infection occurs after contact with fresh water that contains larval forms, called cercariae (Fig. 39.1).1 Skin penetration occurs within 3–5 minutes. Approximately 40% of cercariae that penetrate the skin will eventually become viable adult worms. After penetrating the skin, cercariae lose their bifurcated tails and enter capillaries and lymph vessels and travel to the lungs. After several days, the parasites make their way to the portal venous system, mature, and unite. Pairs of worms then migrate to the superior mesenteric veins (S. mansoni), the inferior mesenteric and superior hemorrhoidal veins (S. japonicum), or vesicle plexus and veins draining the ureters (S. haematobium). Approximately 4–6 weeks after infection, male and female worms mate. The worm pairs begin producing eggs and will do so for the life of the worm, producing up to a few thousand eggs per day.5 The total lifespan of the worm averages 3–10 years, but some may live for more than 30 years.4 Many eggs may pass from blood vessels into adjacent tissues and then through intestinal or bladder mucosa to be shed in feces (S. mansoni and S. japonicum) or urine (S. haematobium).1 S. mansoni eggs are shed singly, while S. haematobium and S. japonicum eggs are released in clumps. Approximately 50% of eggs will be viable upon release, but most will desiccate and die if they do not soon come into contact with fresh water.5 Once in fresh water, the parasite’s life cycle is completed when the eggs hatch, releasing miracidia that infect freshwater snails in temperatures between 20° and 30°C.12 After two generations within the snail, cercariae are then released.1,5,12,13

Clinical Manifestations

Persons with schistosome infection can have a variety of clinical symptoms depending on how recently they were first infected, frequency of re-exposure, and the specific infecting strain of schistosomiasis. In addition, the host susceptibility to disease plays an important role as well as other synergistic comorbidities (such as hepatitis C virus infection). Schistosome infections are frequently asymptomatic for many years while the infection insidiously leads to damage to organs such as the liver or bladder.4 Only approximately 10% of infected persons will develop severe clinical disease.5

Acute infection

At the time of cercariae skin penetration, individuals may experience mild, transitory reactions or a prickling sensation at the site of entry. Within a few hours to a week after cercariae first enter the skin, a macular rash may appear at the site of entry, which may be followed by papules. The papules may be accompanied by erythema, vesicles, edema, and pruritus and may last 7–10 days.5

The adult worms have devised ingenious mechanisms to evade the host immune system and quickly and invisibly migrate to their preordained vessels, where the pair begin to secrete eggs. These eggs are highly antigenic and travel through the blood system until they are deposited. Deposition of eggs produced by the worm pairs, typically 5–7 weeks after infection, causes the symptoms associated with acute schistosomiasis, also known as Katayama fever.5 These symptoms can include fever, headache, myalgias, abdominal pain (in particular, right upper quadrant), and bloody diarrhea.4,5 Eosinophilia is usually detected at this stage, but the absence of eosinophilia does not rule out infection.1 Most persons infected with S. mansoni may also experience respiratory symptoms.14 On physical examination, tender hepatomegaly is a common finding, as is splenomegaly.1 During this acute illness, many but not all patients may shed eggs, and frequently serologic tests are positive.1

Acute manifestations may also include neurologic findings, which may consist of focal or generalized tonic-clonic seizures, especially with infection by S. japonicum.1 Transverse myelitis is a common neurologic manifestation of S. mansoni or S. haematobium. Schistosomal myelopathy is due to egg deposition or embolization in the spinal cord or meninges.4 Neurologic findings have been reported among people with limited exposure to schistosomiasis-infected water, such as soldiers, travelers, and aid workers.1,15

A coinfection of schistosomiasis and Salmonella may lead to persistent Salmonella bacteremia and urinary tract infections. To eradicate the Salmonella in this situation, treatment of schistosomiasis is typically required prior to treatment of Salmonella.5

Chronic infection

Chronic disease is the most prevalent form of schistosomiasis. Chronic manifestations are due to granulomatous reactions stimulated by the antigens released by schistosome eggs.5 The duration and intensity of the infections are related to the amount of antigen released and the severity of the fibrotic deposition in host tissues.12 While granulomas have been detected in tissues throughout the body, including brain, lung, skin, adrenal glands, and skeletal muscle, the species of schistosome and the host susceptibility patterns determine the typical chronic manifestations.12 For example, children may have some unique characteristics of chronic infection manifested by the development of growth impairment, anemia, and memory deficits.1,16

S. mansoni, S. japonicum, and S. mekongi

Egg deposition from these schistosomes typically occurs in the intestine or liver; thus granulomas are most likely to form in these locations.5 Most lesions are found in the colon and rectum.12 Because eggs may be retained in the gut wall, inflammation, hyperplasia, ulceration, microabscesses, and polyposis may be found.5 Symptoms can include colicky hypogastric pain, melena, diarrhea, or constipation. The frequency of symptoms is associated with the severity of infection.1,12 Colonic polyposis is common. A protein-losing enteropathy has also been des-cribed.17 Severe colonic or rectal manifestations may result in stenosis.2

In the liver, perisinusoidal inflammation and periportal fibrosis may result from the granulomatous response.5 Hepatomegaly occurs early in the progression of disease.12 Over time, periportal collagen deposits lead to blood flow obstruction, portal hypertension, varices, variceal bleeding, splenomegaly, and hypersplenism.1,5 The periportal fibrosis can be detected on ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging.1 Sustained heavy infection may lead to a condition known as Symmers’ pipestem fibrosis in 4–8% of patients with chronic infection.18 Until the late stages of the disease, hepatocellular function is preserved and lobular architecture is retained.1 Bleeding esophageal varices is a serious sequalae of fibrotic hepatic schistosomiasis.12 Pulmonary hypertension may develop as a complication in persons with portal hypertension.19

Co-infection with hepatitis B or C virus can lead to accelerated liver damage.1,6 For example, chronic schistosomiasis caused by S. mansoni and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection may result in a higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma than with HBV alone; this effect is not seen in infections with S. japonicum.20,21 In addition, persons with chronic schistosomiasis may have more severe hepatitis B or C infections.22 Persons with more severe forms of hepatosplenic schistosomiasis have greater rates of hepatitis B than the general population.4

S. haematobium

While infection with S. haematobium can occasionally cause mild colonic or hepatic disease, genitourinary disease is the classic manifestation of this disease. Dysuria and hematuria are common in the initial manifestations of the disease, with hematuria appearing 10–12 weeks after infection.1,5

As with S. mansoni infections, chronic manifestations of S. haematobium are also attributed to granulomatous inflammation in response to deposition of eggs in tissue. Chronic manifestations can include dysuria, hematuria, bladder calcifications, ureter obstruction, proteinuria, renal colic, hydronephrosis, and renal failure. These changes can predispose patients to secondary genitourinary bacterial infections. Areas of roughened bladder mucosa surrounding egg deposits visible on cystocopy are pathognomonic.1,5

While there is some controversy regarding the exact role of S. haematobium infections and the development of bladder cancer, squamous cell carcinomas of the bladder are associated with S. haematobium.5,12

In females, infection with S. haematobium causes genital manifestations in approximately one-third. Genital manifestations may include hypertrophic, ulcerative, fistulous, or wart-like lesions on the vulva and perineum.1 While isolated internal disease is less frequent, tubal infertility may be a late complication of chronic infection.23–25 In males, genital schistosomiasis has also been reported6 and S. haematobium eggs have been detected in semen specimens and in lesions noted in the prostate and seminal vesicles.26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree