Fig. 46.1

a–d A 40-year-old patient presented with a lump in a left lateral breast. Ultrasound a mammography b and core biopsy all suggested only a benign fibroadenoma. Excision biopsy was performed in a regional hospital and a 3.5 × 3 × 3 cm tumour was removed. Phyllodes tumour was suspected on histological analysis, and the patient referred to the tertiary hospital Breast Cancer and Sarcoma teams. The final histological consensus confirmed a malignant phyllodes tumour. CT scan performed at 5 weeks from the original excision biopsy c showed a recurrent tumour measuring 3.7 cm, and MRI scan d showed an even larger, intensive tumour measuring 5 × 3.8 × 4 cm. Radical mastectomy including pectoralis fascia was performed, and the axillary lymph nodes were not removed. The patient is symptom-free at 2-year follow-up

Fig. 46.2

An unusual case of malignant phyllodes tumor deep to breast implant and invading through the chest wall into the chest cavity (CT image provided). Extensive resection including the full thickness of chest wall was necessary. Reconstruction with mesh and methyl methacrylate cement sandwich and pedicled latissimus dorsi flap was performed

Three subtypes of PTs are recognized: benign, borderline and malignant. The differentiation is based on the histological characteristics of the stromal elements. Benign PTs behave clinically like fibroadenomas and very rarely recur or metastasize. In contrast, malignant PTs have a tendency to local recurrence and/or systemic metastasis, sometimes within several years after primary treatment [6, 7]. Hence, in most cases, mastectomy is performed, especially if the tumour is large and the breast small to moderate in size. Malignant PTs also warrant long-term follow-up.

Two studies have shown how tp53 staining can underscore malignancy in PTs and that positive stromal immunoreactivity for CD 117 (also known as c-kit positivity) correlates with tumor grade and recurrence [19, 20].

Several studies have shown that malignant PTs share a similar prognosis with primary breast sarcomas. Hence both subtypes of breast sarcoma should be approached with the same management strategies [11, 18].

46.7 Primary Breast Sarcomas

Primary breast sarcomas arise de novo from the mesenchymal tissues of the breast. Predisposing factors are mostly unknown, but some genetic conditions that are associated with soft tissue sarcomas, in general, may be implicated (Li-Fraumeni syndrome, familial adenomatous polyposis and neurofibromatosis type 1). Certain environmental factors such as exposure to alkylating agents, vinyl chloride and arsenic compounds may also be potentially related [8]. In addition, exposure to radiation therapy and the presence of chronic lymphoedema are also known to be associated with the development of sarcoma.

Sarcomas display varying degrees of mesenchymal differentiation. The variety of mature connective tissue cells, such as fat cells, muscle cells or endothelial cells, found in the breast, explains the heterogeneity of the histological breast sarcoma types, which may occur. The most common subtypes are pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma, (myxo)fibrosarcoma, angiosarcoma and spindle cell sarcoma. Several other subtypes (desmoid tumors, liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, stromal sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, haemangiopericytoma, synovial sarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma and neurosarcoma) have been described in very small numbers (see ◘ Fig. 46.3).

Fig. 46.3

An 84-year-old lady with primary extraskeletal osteosarcoma involving lateral breast and axillary fold. No history of radiotherapy. The skin erythema and oedema proved to be atypical vascular proliferation. Excision with 2 cm margins

Angiosarcomas (AS) are considered to be the most malignant of all breast tumors and are thought to arise from the endothelial cell lining of vascular or lymphatic channels. Primary breast AS (not associated with radiotherapy) typically presents as an ill-defined mass in the breast parenchyma in younger females and constitutes only 1 in every 1700–2000 breast cancers [21, 22]. A secondary (radiation-induced) breast angiosarcoma is much more likely to be encountered.

AS differs from other breast sarcomas in that they may metastasize to the axilla [16]. Therefore positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scanning may help in assessing axillary lymph node status prior to surgery.

Immunohistochemical analysis often reveals positivity in AS for factor VIII-related antigen, Ulex europaeus I lectin, CD34 and CD31 [23–26].

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), in spite of their fibrosarcomatous component, are essentially derived from the skin and have more benign features than other soft tissue sarcomas. DFSP is a rare low-grade sarcoma of the skin with a tendency to locally recur after inadequate excision. Metastatic spread is very rare and therefore should be clearly distinguished from conventional sarcomas. Due to the histological tumor-free margins differing greatly from clinical gross margins, wide excision of a few centimetres is recommended [27] (see ◘ Fig. 46.4).

Fig. 46.4

a–b Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of lateral breast. A 44-year-old lady was earlier treated with sclerotherapy for a lateral breast lymphatic malformation. Dermatofibrosarcoma was later diagnosed with MRI and biopsy in the same region. Resection with 2 cm margins was performed

Fibromatosis or desmoid tumors are histologically benign, slow-growing fibroblastic neoplasms originating from musculoaponeurotic stromal elements. They possess an infiltrative and locally aggressive growth pattern with a tendency for local recurrence, but have no metastatic potential. The aetiology is unknown but there is an association with trauma and genetic disorders, e.g. Gardner syndrome. In the breast, desmoid tumours are extremely rare and often misdiagnosed (see ► Chap. 47, for further details). They comprise only 0.2% breast tumors and they may clinically resemble other breast tumors. Until recently, surgical resection with clear margins has been the favoured treatment option. However, the histological extent of the tumor is larger than the apparent macroscopic clinical margins. Although wider surgical resection often results in significant breast deformity [28], and a more conservative approach has been advocated [29], the authors’ own preference is for adequate surgical resection in order to achieve clear margins.

46.8 Radiation-Induced Sarcoma

Ionizing radiation is known to be a potent carcinogen. Radiation can result from natural sources, accidental radiation exposure or cancer radiotherapy. The classical definition of radiation-induced sarcoma is based on criteria proposed in 1948 by Cahan and colleagues [30]:

- 1.

History of radiotherapy

- 2.

Asymptomatic latency period of several years

- 3.

Occurrence of sarcoma within a previously irradiated field

- 4.

Histological confirmation of sarcoma that is histologically unique from the primary cancer

In general, taking into account all anatomical locations, the most common histological types of radiation-induced sarcoma are pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma, osteosarcoma and fibrosarcoma [31] (see ◘ Fig. 46.5). However, in the irradiated breast, angiosarcoma (AS) is the most common type (see ◘ Fig. 46.6).

Fig. 46.5

a–b Radiation-induced osteosarcoma 23 years after mastectomy and radiotherapy. Presentation with a lump below the mastectomy scar. The tumour was excised along with the pectoralis major muscle and reconstructed with a pedicled latissimus dorsi flap

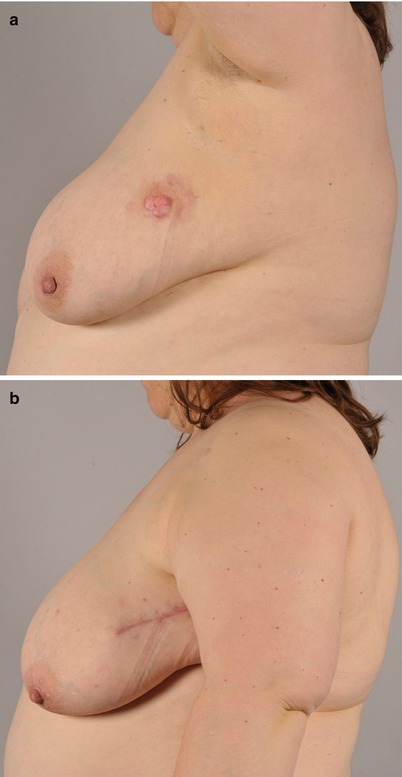

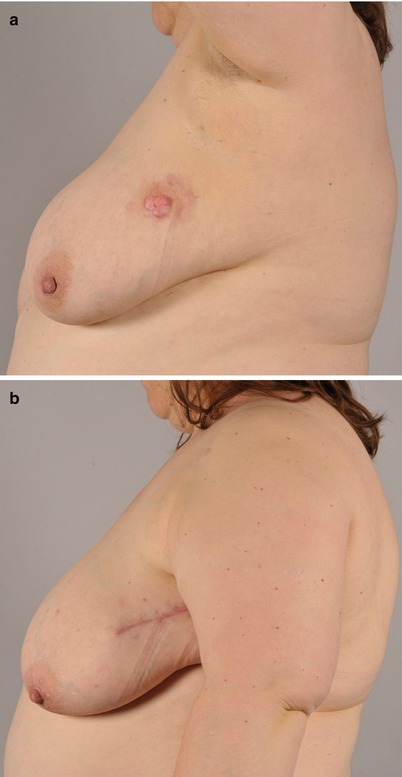

Fig. 46.6

a–b Two cases of radiation-induced breast angiosarcomas. A bruise-like-looking skin lesion at the lateral aspect of breast 4 years after segmental breast cancer resection and radiotherapy. Rapidly progressing angiosarcoma in the left breast 5 years following breast conservative therapy (local excision and radiotherapy). Mastectomy was performed in both cases aiming at 3–4 cm margins

Although secondary AS of the breast is still a rare tumor, it has been increasingly reported as a severe long-term complication of modern breast cancer treatment, in which breast-conserving surgery is combined with radiotherapy. Hence, secondary breast AS usually occurs in older women with a history of breast cancer and treatment with radiotherapy. AS develops after a latent period of 3–25 years (median 7) following radiotherapy [32–36]. Chronic lymphoedema of the breast and arm is another potential risk factor for AS arising from lymphatic vessels. Stewart and Treves in 1948 first described postmastectomy lymphangiosarcoma arising in the upper extremity, breast and axilla after long-standing severe lymphoedema [37].

The secondary form of AS (usually) related to radiotherapy clinically presents as an erythematous patch, plaque or nodule, often with local oedema. It may also initially resemble a bruise. Other early findings include ulceration, eczema and non-pigmented macules. Pain is uncommon. Differential diagnoses include trauma, infection, haemangioma-like lesions or inflammatory carcinoma. Involvement of the breast and surrounding skin can become extensive, and the lesions are commonly multiple [32, 36].

Early diagnosis of AS is important due to the aggressive local nature of the tumor. Unfortunately, there is often a delay in the diagnosis due to patient- and physician-related reasons; typically the small primary reddish purple skin lesion is ignored or not examined histologically at the outset. Furthermore, there may be a difficulty in histologically distinguishing AS from a benign atypical vascular lesion. Due to variable presentation, there should be a low threshold for performing multiple punch biopsies or excision biopsy, to confirm diagnosis. It should be noted that AS may also develop in a breast reconstructed with a pedicled or free flap. In this scenario the tumor develops in any remaining breast or chest wall skin and then spreads into the flap tissue [36].

AS behaves in a different way to most other sarcomas with a propensity for local relapse and systemic dissemination. Local skin recurrences can be extensive and require major plastic surgical reconstruction after resection, such as with skin grafts or pedicled or free flaps [37]. This high local recurrence risk may in part be explained by AS possessing diffuse infiltrative behaviour and a tendency for widespread local intravascular spread. This is in contrast to many other soft tissue sarcomas that often have a capsule (or «pushing border»). In many advanced cases AS seems to have a multifocal pattern. Therefore wide peripheral surgical macroscopic margins of at least 3 cm are recommended. In addition, close and thorough follow-up is essential involving clinical photography and MRI. The axilla is not usually treated in secondary AS, especially when an earlier axillary dissection has been performed for the primary breast carcinoma [32–36] and/or there is no evidence of axillary involvement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree