Fig. 21.1

Patient with ptosis and left breast cancer. The left breast was reconstructed with a DIEP flap. A mastopexy was performed on the right to match the more aesthetic reconstructed left breast

Although the reconstruction of a mound has become much more predictable, the reconstruction of a nipple areola complex has been challenging. This is mostly due to a loss of projection of the nipple over time. There have been many designs for nipple and areola reconstruction. All utilize some form of interposed rotational flaps to create the nipple. These flaps are harvested from the flap skin paddle in autologous reconstruction or the mastectomy skin flaps in implant reconstruction.

The “skate” flap was an early design that incorporated interposed flaps [2]. In 1994, Bostwick et al. reported a nipple reconstruction with the C-V flap [3]. The two flaps are interposed and the donor sites closed primarily. This technique has many variations (Fig. 21.2).

Fig. 21.2

The SKATE flap: note that two flaps of mastectomy or flap skin are interposed to form the nipple skin flaps

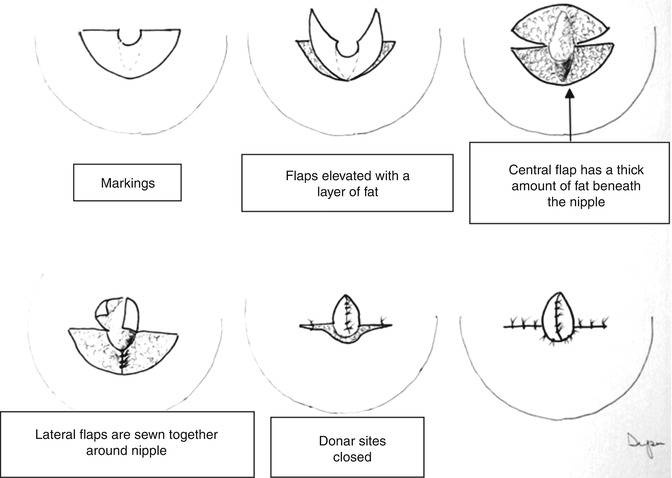

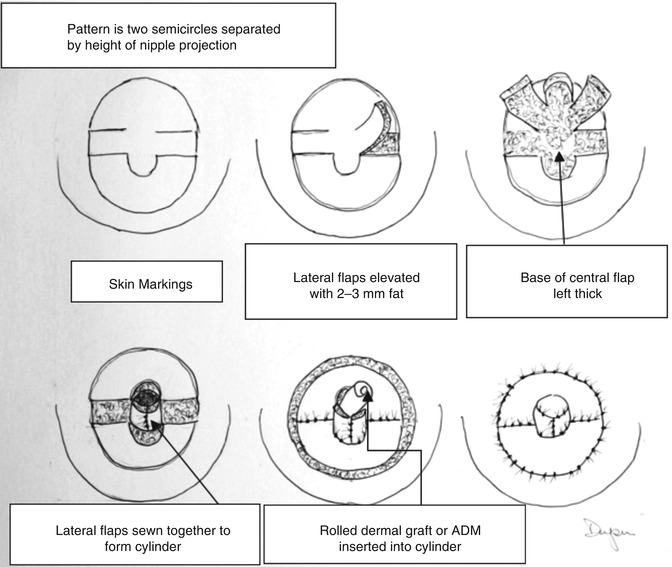

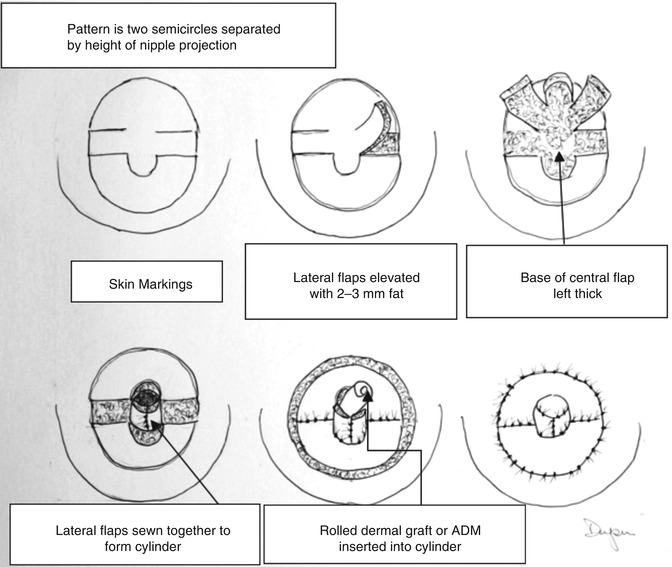

We have proposed a procedure that also uses interposed flaps, but the donor site is closed in a circular fashion, which looks like the edge of the areola. A dermal graft, harvested from the abdominal “dog ear” or acellular dermal matrix, is inserted into the flap to increase projection of the nipple (Figs. 21.3 and 21.4).

Fig. 21.3

Nipple reconstruction with dermal graft or ADM

Fig. 21.4

Nipple reconstruction with dermal graft

Once stable, the nipple and the areola can be tattooed to match the pigment on the other areola. This is typically the last step in the reconstruction (Fig. 21.5).

Fig. 21.5

The completed reconstruction, with right DIEP flap, right nipple areola reconstruction, and left mastopexy

Complications in Breast Reconstruction

Fortunately, life-threatening complications are rare and are still most commonly associated with the development of a postoperative pulmonary embolism. Adhering to the recommendations of the American College of Chest Physicians, accounting for thrombosis risk factors and prophylaxis should minimize this potentially lethal complication [4].

Unfortunately, breast cancer patients are frequently in the 41–60 age group (1 point), and many or obese (1 point). They all have malignancy (2 points) and all have major surgery (2 points). Thus, a reconstructive patient who is over the age of 60, obese, and undergoing a flap procedure will start with a score of 6. These patients should have chemoprophylaxis unless contraindicated with low molecular weight heparin as our drug of choice. It requires no monitoring and poses minimal risk of bleeding, even if given preoperatively [4]. We treat our patients with a score of 6 or less for a week postoperatively. Patients with risk factors of 7 or greater require longer prophylaxis.

There is no specific risk of infection that differs from other clean surgical procedures, other than periprosthetic infection in implant reconstructions. These infections can become life threatening and lead to sepsis if not addressed.

Seroma formation is common in the donor sites of autologous tissue. They tend to occur more frequently in obese patients. Seromas should be prevented if possible, with long-term effective drainage and the use of “quilting” sutures, which fix the flap down to the underlying deep fascia. Once a seroma is identified, it is best treated with an ultrasound-placed indwelling pigtail drain, and the area should be compressed. Most are amenable to nonsurgical treatment; occasionally the seroma cavity may require excision and a second set of quilting sutures and drains placed. Seroma problems with expanders or implants are addressed specifically in the chapter on nonautologous reconstruction.

Hematomas are more commonly associated with autologous reconstruction. The more common sources of hematoma are the lateral chest wall when an axillary dissection has been done or from the edges of the flap or de-epithelialized dermis. Care should be taken with hemostasis when trimming or de-epithelializing the flaps. It is important to recognize evolving hematomas when flaps are done, because the pressure from the hematoma may compromise the outflow from the flap. Hematomas should be addressed by promptly returning to the operating room, removal of hematoma, and irrigation. Waiting for a hematoma to resolve spontaneously is risky, because the hematoma will cause thinning of the soft tissues and will likely drain through the wound, allowing ingress of infection.

Problems with mastectomy flap necrosis are associated with cellulitis, wound disruption and exposure of the prosthesis. Patients with macromastia or significant ptosis of the breast frequently require excision of excess skin. This leaves additional wounds and increases the chance of necrosis and infection. Small areas of partial necrosis can be treated with careful wound care and will frequently heal without implant exposure, but larger areas of necrosis are very troublesome. Large amounts of mastectomy flap necrosis may require autologous reconstruction of either the entire mound with another flap or to replace the debrided skin (Fig. 21.6).

Fig. 21.6

Exposed prosthetic; note poor-quality soft tissue coverage

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree