Fig. 14.1 Thoracoabdominal approach to an upper (right) quadrant sarcoma. The oblique incision starts above the umbilicus and is extended through the 9th intercostal space. The diaphragm is opened. The right lobe of the liver and right lung are exposed.

Upper Quadrant Sarcomas

Upper Quadrant Sarcomas

For upper quadrant retroperitoneal sarcomas, the patient is placed in a lateral or semi-lateral position with the affected side up. An incision from about the mid distance between the xiphoid and umbilicus is extended obliquely to the costal margin. This incision is carried through the subcutaneousfat,theanterior rectus sheath, rectus abdominis, posterior rectus sheath and peritoneum and, more laterally, toward the costal margin through the external oblique, the internal oblique, transversus abdominis muscles, transversalisfascia,and peritoneum. This incision from the midline to the costal margin provides sufficient exposure for the surgeon to explore the abdomen with regards to possible metastatic disease that might militate against or alter the course of resection of the tumor. Even in the presence of modest metastatic disease, however, in general, it is best to resect a primary retroperitoneal sarcoma and, if possible, to resect all other metastatic foci which provides good palliation and prolongation of life.1 This incision provides an ample opportunity to assess the location of the tumor and, therefore, more accurately guide the direction of the incision into the lower chest which, depending on the exact location of the tumor, may be extended into the 9th, 10th, or 11th intercostal space. The costal margin is divided and a small segment of the costal margin is removed. The diaphragm is incised for 3 cm and this allows the insertion of a self-retaining retractor between the ribs (Fig. 14.1). One can then estimate how far posteriorly one may have to expand the thoracic portion of the incision in order to have the necessary exposure. The diaphragm is incised, as necessary for sufficient exposure, close to its insertion to the ribs so that the bulk of the diaphragm in the central area is not denervated. If there is, however, actual involvement of the diaphragm, the incision into the diaphragm will have to accommodate and circumscribe the area of involvement around the tumor. Visceral attachments are evaluated and whatever viscera can be separated off the tumor surface without coming too close to the tumor are dissected off the tumor. The splenic flexure of the colon and the hepatic flexure on the left and right sides, respectively, are structures to be assessed as to whether they are close to the tumor or not. In order to evaluate the visceral attachments to the tumor surface, however, it is generally desirable to mobilize the tumor posterolaterally to some extent and thus facilitate dissection between the tumor and other viscera. The peritoneum anterior and lateral to the tumor is incised around the mass and the retroperitoneal plane between the peritoneum and the lower chest and the upper abdominal wall is entered. If this plane appears to be uninvolved, one can continue on the same plane. Otherwise, one may have to enter the plane between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique or even that between the internal oblique and external oblique. In some situations, one may have to remove a portion of the lower chest or upper abdominal wall in its entire thickness. Usually, one can dissect between the tumor and transversus abdominis laterally and the tumor and quadratus lumborum posteriorly.

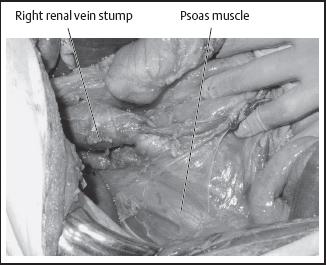

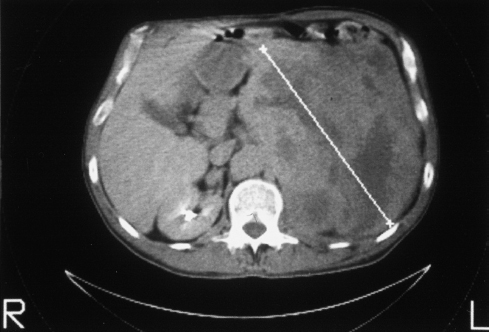

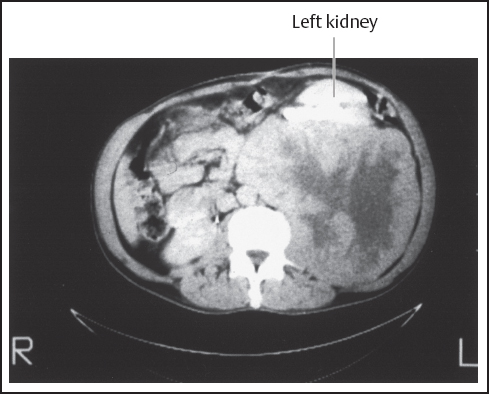

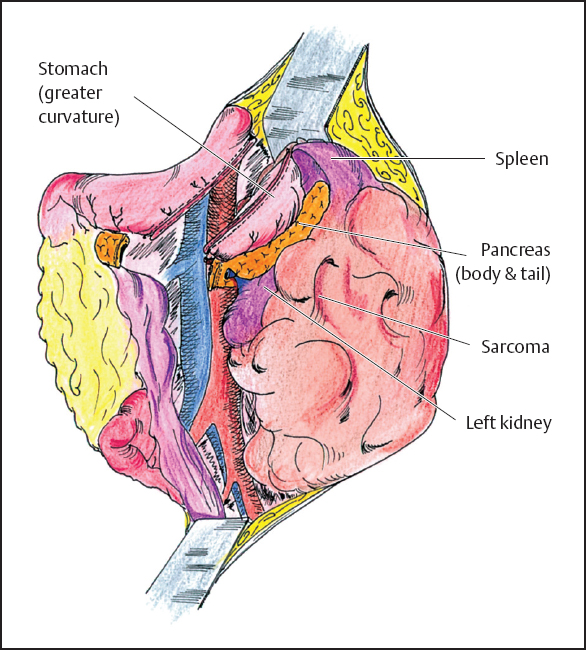

There should be no hesitation, however, to remove either of these two muscles, should the tumor appear to be attached to either of them. If the respective flexure of the colon seems to be adherent to the tumor surface, then the bowel proximal and distal to the area of involvement is divided with a stapling device and the appropriate portion of the mesocolon, which is close to the tumor, is divided at its base so that this segment of large bowel, as well as its mesocolon, remain attached to the tumor to be removed en bloc with the latter. In the left upper quadrant, dissection through the lienorenal ligament allows the mobilization of the spleen and tail of the pancreas along with the tumor mass. Posterolateral to the spleen, the kidney is encountered and one has to decide whether it should be resected en bloc with the tumor or not, depending on its proximity to the tumor mass. The gastrocolic ligament is divided, entry into the lesser sac is gained and through this opening one can easily find the splenic artery coursing on the superior border of the pancreas and proceed to ligate and divide this artery. Immediately above and at the base of the mesocolon, the inferior border of the pancreas is identified. The inferior mesenteric vein, if close by, can be ligated and divided and then with a combination of blunt and sharp dissection, one circumferentially dissects and exposes both the anterior as well as the posterior surface of the pancreas medial to the area involved by the tumor. On the posterior surface of the pancreas, the splenic vein can be visualized, ligated, and divided at the same level as the splenic artery previously was divided. The pancreas itself can be divided either with a stapling device or by using mattress sutures to control any bleeding from the pancreatic parenchyma. Any attachment of the tumor to the greater curvature of the stomach can be dealt with by stapling that portion of the stomach so that the involved area remains on the surface of the tumor. With the thoracoabdominal incision used, one has good access to the esophagogastric junction and, therefore, one should be able to free both the posterior and anterior wall of the stomach medial to the area of involvement in the greater curvature for a left-sided retroperitoneal sarcoma. If the kidney appears to be involved, then it is dissected posteriorly and mobilized so that the renal artery may be identified, ligated, and divided. The renal vein is exposed from the anterior aspect of the kidney as it crosses transversely the abdominal aorta, it is dissected, vascular clamps are applied and it is divided, the two ends being oversewn with running vascular sutures. Because of the width of the renal vein, it is safer to do so than simply sutureligate the stump of the renal vein (Figs. 14.2–14 .5).

Fig. 14.2 Soft tissue sarcoma of the left upper quadrant, resected through a left thoracoabdominal incision in combination with a midline abdominal incision.

Fig. 14.3 Left upper quadrant sarcoma showing the left kidney displaced anteriorly by tumor, also resected through a left thoracoabdominal incision.

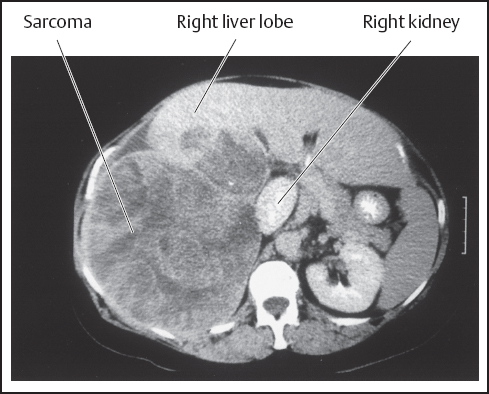

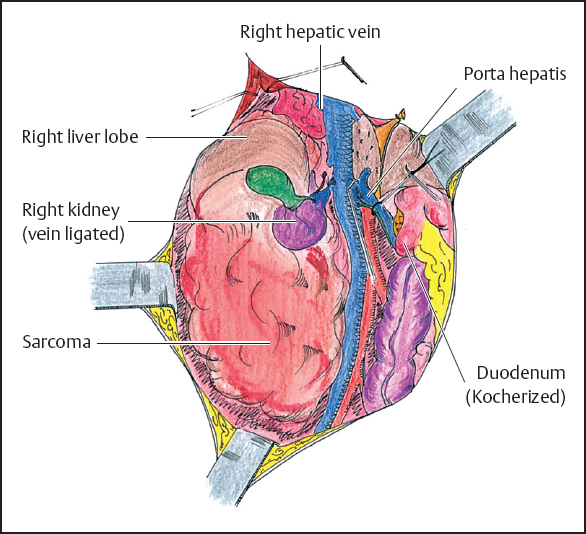

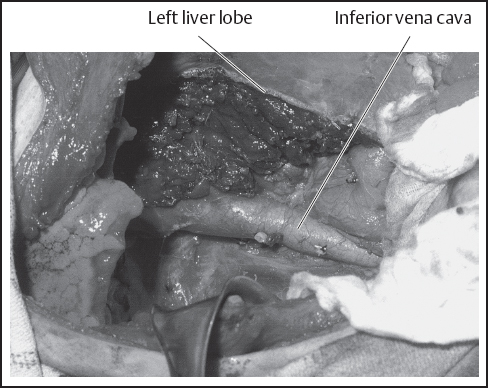

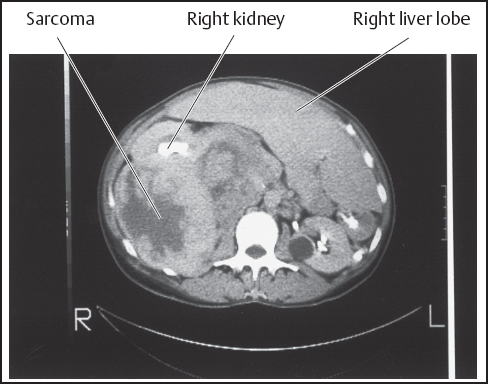

For sarcomas of the right upper quadrant, the patient is placed in a left lateral position with the right side up. The pleural space is entered and the diaphragm is incised sufficiently for exposure. Posterolateral mobilization of the tumor is then performed by dissecting behind the peritoneum and pleura so as to leave the peritoneum and lower portion of the pleura on the tumor surface. As on the left side, if there is invasion of the underlying muscular layer, then the dissection reverts to a more superficial plane between the muscles so as to maintain at least one muscle layer that appears grossly normal on the tumor surface. For involvement by the tumor of the diaphragm, the respective portion of the diaphragm is circumscribed around the area of involvement so that it can be left on the tumor surface. The right triangular ligament of the liver is incised peripherally. In case of liver involvement, which would be the right lobe in this case, the porta hepatis is exposed, the gallbladder is removed and the right hepatic duct, the right hepatic artery, and the right branch of the portal vein are sequentially dissected, ligated, and divided. For the right branch of the portal vein, because of its short length, it is best after this vessel is dissected out with a right-angled clamp to apply vascular clamps tightly before dividing it. It is wise to place a vascular suture on each side of this vein for extra control and safety. The venous trunk itself is then divided and the stump on each side is sutured with the vascular suture. If a vascular clamp is not applied tightly and holding sutures are not placed, the proximal stump may retract through the jaws of the vascular and disappear behind the hepatoduodenal ligament. If this perioperative complication occurs, the proximal stump of the right branch of the portal vein should be promptly compressed against the rest of the hepatoduodenal ligament from a posterior approach with the left index finger and brought closer to the lateral edge of the hepatoduodenal ligament where it can be sutured. This controls the bleeding. However, at the end of the procedure, after a right hepatic lobectomy, the choledochus must be opened in order to make sure that the vascular sutures do not involve any part of the main biliary duct. This type of mishap, however, can be avoided if the vascular clamps are applied tightly on each end of the short length of the right branch of the portal vein and vascular sutures are placed on either side (two on each side). Kocherization of the duodenum, incision of the gastrohepatic ligament, passage of a tape around the structures of the porta hepatis and then through a short segment of red rubber catheter (Rummel tourniquet) is an additional safety measure for control of potential bleeding (Pringle maneuver).

Fig. 14.4 Sarcoma of the left upper quadrant resected with the left kidney, spleen, distal pancreas, and diaphragm.

Fig. 14.5 Left upper quadrant sarcoma after exposure and before removal. The tumor has invaded the greater curvature of the stomach, the spleen, the tail of the pancreas, and the left kidney. The stomach and pancreas are stapled; the renal and splenic vessels are ligated. The sarcoma is removed en bloc with these organs.

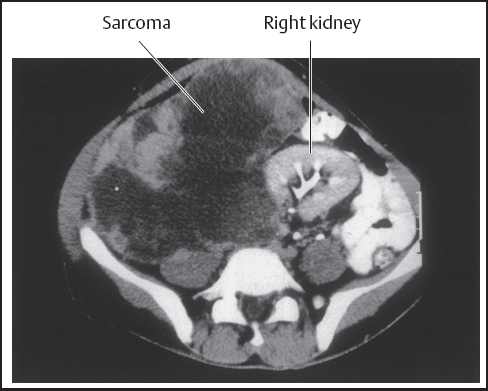

Fig. 14.6 Sarcoma of the right upper quadrant involving the right lobe of the liver and right kidney displaced medially. It was resected through a right thoracoabdominal incision in combination with a midline incision.

The right hepatic vein, if it is easy to be dissected, is ligated and divided. If not, later intraparenchymal ligation and division of this vein may be safest. One incises the Glisson’s capsule from the gallbladder bed to the confluence of the hepatic veins and proceeds to cut through the hepatic parenchyma, being careful at all times so that the plane through the hepatic parenchyma is aiming to the right of the inferior vena cava. One member of the operative team should have a hand, therefore, on the lateral edge of the inferior vena cava so that it can be ascertained that the dissection proceeds in that direction through the hepatic parenchyma and does not veer to the other side, compromising blood supply to the remaining lobe of the liver.

On the right side, the hepatic flexure of the colon has to be dealt with and mobilized by dividing the peritoneal reflexion lateral to the colon and the colon itself dissected off if not too close to the tumor surface. If it is, then the appropriate segment of the colon is divided proximal and distal to the area of involvement and the corresponding mesocolon is left on the surface of the tumor for en bloc resection. The duodenum is Kocherized, the inferior cava is exposed clearly and the right renal vein is visualized. On this side, the right gonadal vein enters the inferior vena cava a few centimeters below the right renal vein and, if the tumor extends in front of the kidney, the gonadal vein is ligated and divided (on the left side, the gonadal vein drains directly into the left renal vein). If it appears that the tumor involves the kidney, the kidney is mobilized posterolaterally and the right renal artery is dissected, ligated, and divided from the posterior approach and then the renal vein is ligated and divided, preferably using vascular clamps through an anterior approach. If necessary, a cuff from the inferior vena cava is removed through the application of a lateral vascular clamp (Figs. 14.6–14.9). Thoracoabdominal incisions are well tolerated even by patients of advanced age.2

Fig. 14.7 Right upper quadrant sarcoma after exposure and before resection. The duodenum is Kocherized. A Rummel tourniquet is applied to the porta hepatis. The tumor has invaded the right lobe of the liver and the right kidney. The right branch of the portal vein is clamped, the right hepatic vein is stapled, the cystic duct and the renal vessels are ligated. The exposure between the right side of the vena cava and the tumor is accomplished.

Flank Retroperitoneal Sarcomas

Flank Retroperitoneal Sarcomas

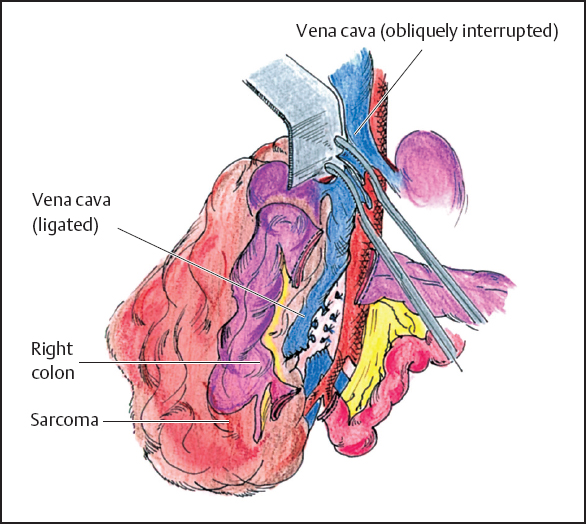

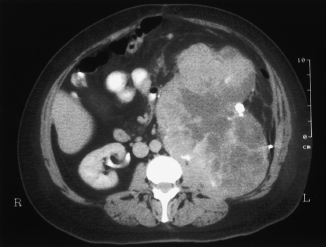

These tumors are dissected with the patient in a lateral position with the affected side up. A flank incision is made over the protuberance of the tumor extending from the midline of the abdomen as far posteriorly as necessary in order to mobilize and dissect the tumor. This is combined usually with a midline incision. The approach again, as in the upper quadrants of the abdomen, is a combination of both transperitoneal as well as extraperitoneal dissection. Through the transperitoneal part of the incision, the respective colon is mobilized whenever that seems to be appropriate. Otherwise, the segment of colon that is attached to the tumor is divided proximal and distal to the area of involvement using a stapling device and the corresponding mesocolon is also divided so that the involved segment of colon and respective mesocolon are left with the tumor. Posterolaterally, the tumor is dissected off the lateral portion of the abdominal wall, removing any layers of muscle that may be too close to the tumor. Rarely, the tumor may be close to the femoral nerve which at this level is protected by the psoas muscle, and unless the psoas muscle is involved, it is not likely to be encountered in this location. As the mobilization of the tumor comes close to the midline on the right side, lumbar tributaries to the inferior vena cava are ligated and divided. The kidney may be involved and may have to be dissected and removed with the tumor mass. In the case of involvement of the inferior vena cava, this vein is dissected out proximal and distal to the tumor. The infrarenal portion of the inferior vena cava may be removed en bloc with the tumor without great difficulty. In this case, the inferior vena cava is exposed on its left side and the left renal vein and its insertion into the inferior vena cava behind the duodenum is exposed. In the case of a retroperitoneal sarcoma of the flank on the right side (Fig. 14.10) involving the inferior vena cava (Fig. 14.11) and kidney, one dissects the inferior vena cava above the level of the renal veins, both right and left, and below at the confluence of the right and left common iliac veins. At the lower end of the inferior vena cava above the confluence of the common iliac veins vascular clamps can be applied and the vein divided and oversewn, ligating and dividing any lumbar tributaries to this segment of the vein. Superiorly, two vascular clamps are applied obliquely on the inferior vena cava from below the entry point of the left renal vein to a point above the entry of the right renal vein to the inferior vena cava. In this fashion, one can remove the lower part of the infrarenal part of the inferior vena cava and preserve intact the continuity of the left renal vein into the inferior vena cava, while the tumor mass, the involved portion of the right colon, and the right kidney can be removed together with the mass (Figs. 14.12, 14 .13).

Fig. 14.8 Operative field after resection of the sarcoma in Fig. 14.6 showing the inferior vena cava and parenchyma of the remaining left lobe.

Fig. 14.9 Sarcoma of the right upper quadrant displacing but not involving the right lobe of the liver. The right kidney is displaced anteriorly.

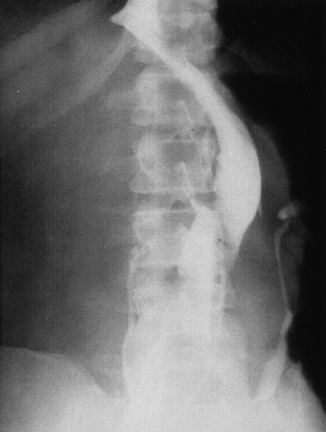

Fig. 14.10 Sarcoma of the right flank displacing the right kidney to the left of midline. It was resected through a flank incision in combination with a midline abdominal incision.

For a retroperitoneal sarcoma of the left flank, the flank approach is again utilized with the patient in a lateral position with the affected side up (Fig. 14.14). A flank incision is made and this is extended to the mid-line. For both right-sided and left-sided flank tumors, it is necessary to perform this incision extending above and below the area where the flank incision meets the midline and, therefore, create an angled “T” incision which provides adequate exposure for both the retroperitoneal as well as for the transperitoneal part of the dissection. Any visceral attachments to the tumor mass on the left side are dissected out if possible. Otherwise, the respective segment of large bowel and possibly small bowel is separated from its continuity and its respective mesentery is divided to be with the tumor mass. Posterolateral mobilization is again performed so that the tumor is mobilized first from its bed and then any connections with the aorta can be dealt with more effectively and safely.

Fig. 14.11 Same tumor as in Figure 14.10 showing displacement of the inferior vena cava (IVC), which also had to be resected below the level of the left renal vein (the right renal vein and kidney were removed en bloc with the IVC).

Fig. 14.12 Right flank sarcoma after exposure and before resection. The vena cava, right kidney, and ascending colon are invaded. The distal ileum and transverse colon are stapled, the vena cava is stapled or sutured after iliac convergence, the lumbar tributaries are suture-ligated, a vascular clamp is applied obliquely below the left renal vein ostium. The tumor is resected en bloc with the ascending colon, right kidney, and infrarenal vena cava.

Fig. 14.14 Recurrent sarcoma in the left flank resected through a left flank incision in combination with an abdominal incision. The left colon and kidney were removed en bloc.

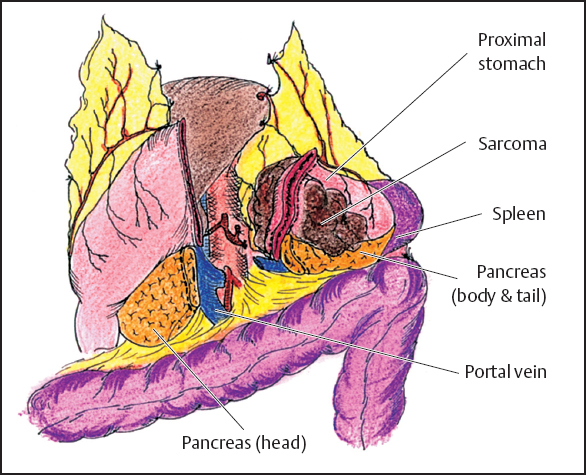

Fig. 14.15 Lesser sac sarcoma after exposure and before removal. The tumor invades the proximal stomach, tail of the pancreas, and spleen. The proximal stomach and tail of the pancreas are stapled; the left gastric and splenic arteries are divided. The splenic vein is also ligated. The portal vein is exposed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree