Figure 28.8 A failed TMA with remained fibrotic and necrotic tissue (A), followed by revisional surgery with STSG (B) and final clinical outcome (C).

Technical Principles

When a Lisfranc amputation is performed, one will encounter the tibialis posterior, tibialis anterior, and peroneal tendons. The tibialis posterior tendon has multiple inserts, the main insertion is to the base of the navicular, then to the bases of the second through fourth metatarsals and the three cuneiforms. This muscle inverts and plantarflexes the foot; the insertion to the navicular and cuneiforms should be preserved because it is not encountered during the procedure. The tibialis anterior tendon inserts into the base of the first metatarsal and medial cuneiform. Its main function is to dorsiflex the foot. If the insertion is disturbed, the detached portion should be reattached to the proximal aspect of the medial cuneiform to preserve the function. The peroneal tendons are the strong evertors of the foot, and if the insertion is lost the tendon can be reattached to the cuboid.

Because of the proximity of the amputation, the transverse arch is disrupted, with loss of peroneal and extensor tendons resulting in a varus deformity. When there is loss of function of the muscles described in the preceding, the Achilles tendon gains advantage and an equinovarus foot deformity can occur. An Achilles tendon lengthening or complete tenotomy may be performed in conjunction with various tendon transfers (25). Variety of tendon transfers and Achilles tendon lengthening have been proposed, but results still can be suboptimal.

Operative Technique

In Lisfranc amputation, the operative technique is virtually identical to TMA. A fish-mouth incision is used with disarticulation performed at the tarsometatarsal joints. DeCotiis believes in salvaging the bases of the second and fifth metatarsals because the peroneus brevis, peroneus tertius, and the lateral band of plantar fascia attach to the base of the fifth metatarsal (24). Early (26) recommends disarticulation of all the tarsometatarsal joints except the base of the second metatarsal because it plays a keystone position, providing stability to the medial cuneiform through the network of plantar ligaments. If the fifth metatarsal is disarticulated, the soft tissue structures are then reflected subperiosteally from the fifth metatarsal base to maintain the integrity of the soft tissue attachment of these tendons. Reattachment of these structures to the lateral aspect of the exposed cuboid and surrounding tissue to preserve some eversion control to the foot is highly recommended. The foot should be in a slightly everted, dorsiflexed position when securing the tendons to the cuboid. The peroneus longus and tibialis anterior tendons should be secured to surrounding soft tissue. It is important to remove as much articular cartilage as possible from the cuneiform and cuboid surfaces to avoid cartilaginous necrosis. Achilles tendon lengthening or complete tenotomy may also be performed (Fig. 28.9).

CHOPART AMPUTATION

François Chopart, a French surgeon, was credited with disarticulating the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints while performing an amputation (24,26,27). Now those joints bear his name and the joints are also known as transverse tarsal or midtarsal joints. After amputation, only the talus and calcaneus are left of the foot. Numerous surgeons soon abandoned this procedure because it invariably led to equinus deformity, resulting in distal stump ulceration, infection, and subsequent proximal amputation. MacDonald (27) in 1955 published a small series study of Chopart amputations treated successfully with modified prosthesis. Bingham (28) concurred with MacDonald in his result of Chopart amputation in a paper published in 1970; however, both believed that transfer of the anterior tibialis tendon to the talar neck was necessary to control deformity of the rearfoot.

Indication

Chopart amputation is mainly performed in patients with serious midfoot infection. When performing a definitive surgery, Chopart amputation requires viable heel pad. When Syme amputation is anticipated, Chopart amputation can be useful as a preliminary procedure.

Technical Principles

When compared with the Lisfranc amputation, the frontal plane varus deformity is rare because the amputation is performed proximal to the transverse arch, and tendon insertions of tibialis posterior and tibialis anterior are eliminated, but the foot shortens even further (29). The Achilles tendon is a lone tendon that is attached to the foot, causing sagittal plane deformity. An open or percutaneous transaction of the Achilles tendon is recommended. Ideally, transferring the tibialis anterior tendon medially, the extensor tendons laterally, and Achilles tendon lengthening should be performed (26,29).

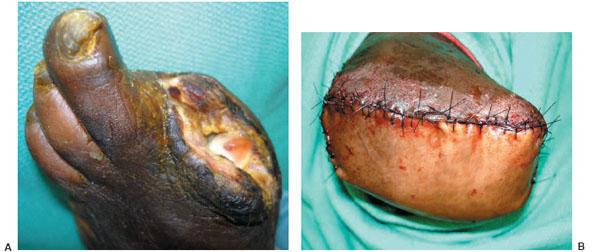

Figure 28.9 A patient with severe PVD and nonhealing hallux amputation (A), followed by a Lisfranc primary amputation. The vascular surgery team was consulted, and preoperative vascular invasive tests determined the level of amputation (B).

Once again, a thickened plantar flap is used from the arch, but it is not as durable as the skin from the plantar forefoot. Early, many surgeons believed that after Chopart amputation patients are more prone to developing plantar lateral deformity, callus formation, or ulceration on the distal anterior aspect of the stump.

Operative Technique

Achilles tendon lengthening or a complete tenotomy may be performed first. Next, the incision is made proximal to the navicular tuberosity and extends dorsally between the fifth metatarsal base and lateral malleolus. Then the medial and lateral incisions extend distally along the first and fifth metatarsal mid-shafts and carried plantarly. Initially, we recommend creating a larger and longer plantar flap which can then be revised to fit the shape of the foot. It is vital to remember to handle the flap in an atraumatic manner.

Next, the tibialis anterior tendon is identified and dissected from the insertion site on the dorsal surface of the base of the first metatarsal and medial cuneiform. To access the Chopart’s joint, use a key elevator to elevate the dorsal soft tissues from the midtarsal joint. Once the joint is identified, using a blade, the foot is sharply disarticulated at the midtarsal level. All tendons except for the tibialis anterior tendon are pulled distally and transected as proximally as possible. The tendons are allowed to retract. If there is a bony prominence on the anterior process of the calcaneus and dorsal talar head, then it can be resected appropriately. Complete cartilage removal from the talus and calcaneus can lead to better flap adherence (26).

The tibialis anterior tendon is transferred into the neck of the talus through a hole drilled in the neck of the talus. The tendon is then sutured upon itself and the extensor tendons are carefully sutured to the fascia and soft tissue of the sole of the foot. The incision site is closed using nonabsorbable sutures. A drain is inserted at the surgeon’s discretion. Care is taken not to put too much pressure when wrapping the wound to cause iatrogenic tissue ischemia. When placing the foot in a well-padded posterior splint, the talus is slightly placed in a dorsiflexed position in relation to the tibia, and the calcaneal tuberosity is parallel to the long axis of the tibia (Figs. 28.10 and 28.11).

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

The postoperative course of Lisfranc and Chopart amputation is similar to TMA. Depending on the underlying cause for the amputation, the wound should be checked daily and immobilization in a splint should be continued until the wound is healed. Sutures are removed only when the wound is healed. Weight-bearing is not permitted until the soft tissues or transferred tendons have healed and stabilized.

The goal of these amputations is to provide independent weight-bearing limbs. In a Lisfranc amputation, once the wound has healed completely, the patient may benefit from a Plastazote forefoot filler with a rocker-bottom shoe, with the rocker positioned more proximally. These inserts may benefit the patient in ambulation to decrease plantar surface pressure. Commonly, patients with Chopart amputation need a customfitted ankle foot orthosis (AFO) with a filler to hold a shoe adequately.

COMPLICATIONS

Complications of the Lisfranc and Chopart amputations are similar to those in TMA, which include residual equinus/equinovarus deformity leading to ulceration of the stump, necrosis of incision line, delayed healing, proximal amputation, and recurrent ulceration. Chopart amputation tends to be more mechanically unstable and may predispose to anterior subluxation of the ankle in diabetic neuropathic patients.

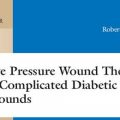

Figure 28.10 A failed Lisfranc amputation (A) converted into a Chopart amputation (B). Please note the local advancement flaps and wound closure free of any tension.

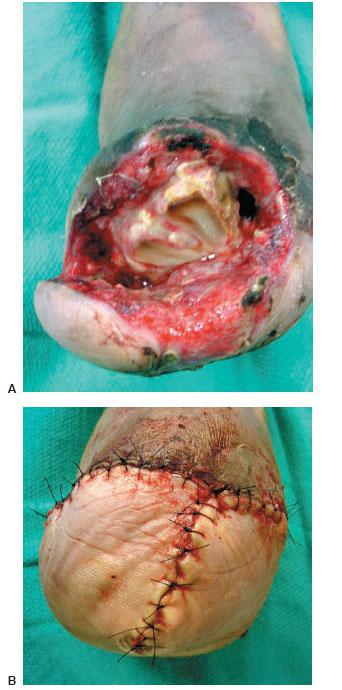

Figure 28.11 A patient with a limb-threatening infection and necrotizing infection (A–C), followed by an open Chopart amputation (D).

CALCANECTOMY

The calcaneus is part of the hindfoot that plays a vital role in weight-bearing and gait. When an infection or osteomyelitis occurs in the calcaneus, it poses a unique problem. The calcaneus receives most of its blood supply from nutrient branches of the posterior tibialis and peroneal arteries (30). The calcaneus can be vulnerable to conditions affecting the microvasculature, such as DM and PVD. Eradication of infection is important to reduce associated morbidities and further complications of proximal amputation, contralateral lower extremity amputation, and amputee ambulation energy costs.

A calcanectomy involves either portion of calcaneus, known as a partial or subtotal calcanectomy, and a total calcanectomy. The first such procedure was performed by Gaenslen in 1931 (31). He treated 11 patients with hematogenous osteomyelitis of calcaneus using a midline posterior incision approach, splitting the bone longitudinally into medial and lateral halves, débriding infected cancellous bone, and maintaining the integrity of the cortex by hollowing out the calcaneus. He reported that 91% healed primarily and one healed with secondary intention. The scars on the heel were found to be painless and well-adapted to weight-bearing, and all the patients were able to walk independently.

Despite an overall satisfaction with the surgical approach, numerous investigators found this technique to bring disappointing long-term results. In 1974, Martini et al. reported results of 20 cases of partial or total calcanectomy with excision of local infected soft tissues based on preoperative radiographs and in some cases tomograms for the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis (32). After experiencing wound complications from using a horseshoe-shaped incision, the authors modified their technique to a posterior longitudinal incision near the midline that would incorporate any nearby sinus tracts. The authors reported eradication of infection in 19 cases and postoperative complications of abscesses, a papilloma of the surgical scar, and an eventual proximal amputation of the foot. In their study, 17 patients resumed an effective or even nearly normal ambulation, with or without an orthotic shoe insert. The authors concluded that partial or total calcanectomy provided good results with return to function and eradication of infection.

In 1981, Crandall and Wagner reported the largest of these series (33). This study included 31 patients who underwent partial or total calcanectomy in over a 10-year period. Osteomyelitis of the calcaneus was documented in 20 patients, including all 18 patients with DM. The authors incorporated ulcerations in the posterior vertical incision and all wounds were closed primarily over a drain. Of the 18 diabetic patients, eight underwent partial calcanectomy and the remainder underwent total calcanectomy. During the follow-up it was noted that non-diabetic patients had 92% success rate versus only 33% in diabetic patients. However, the authors still concluded that partial or total calcanectomy was indicated for severe ulceration of the heel, with or without calcaneal osteomyelitis with resumption of similar ambulatory status after calcanectomy. In 1998, Baumhauer et al. performed a retrospective review of total calcanectomy for the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis of the calcaneus in eight patients (34). The authors reported excellent or good results in four patients, fair results in two patients, and poor results in two patients. The authors concluded that, after addressing the vascular status of the limb and the integrity of the surrounding soft tissue envelope, total calcanectomy was an effective treatment alternative to transtibial amputation in patients with chronic osteomyelitis of the calcaneus. In 1999, Baravarian et al. reported on 12 patients, 10 of whom healed completely. Furthermore, all of the patients who were ambulatory preoperatively were able to ambulate postoperatively (35).

Indications

Indications for partial or total calcanectomy include osteomyelitis of the calcaneus, ulceration of the heel, deformity of the calcaneus (i.e., fracture malunion), and primary tumors of the calcaneus (33–35). Calcanectomies are particularly valuable in convalescent patients or paraplegia, in which patients are predisposed to recurrent decubitus ulcers of the heel because of the continued presence of pressure and the compromised, less mobile integument found at the posterior heel (36). Last, when the patient in question has been indicated for calcanectomy, the next decision to make is whether to perform a partial or total calcanectomy. These patients should be chosen carefully; Syme’s will not be an option in these patients because they lack the soft tissue required to cover the distal tibia and fibula.

Technical Principles

The decision to plan for a partial versus total calcanectomy should be made after review of relevant imaging studies. Radiographs, in the setting of chronic osteomyelitis, may demonstrate bone resorption, especially in the posterior metaphyseal equivalent portion of the bone (31). Previous authors have noted that when compared with the extent of disease found in preoperative radiographs during surgery, the radiographs may underestimate the degree of disease in calcaneus (32). Advanced imaging techniques such as nuclear imaging or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to help diagnose osteomyelitis and determine the extent in the involved bone.

Partial calcanectomy is recommended if the preoperative imaging studies demonstrate subtotal involvement of the calcaneus; if the anterior articular portions of the calcaneus are spared, then the partial calcanectomy will be adequate in eliminating all diseased bone while maintaining the talocalcaneal and calcaneocuboid articulations (Fig. 28.12) (32,33). If the disease process appears to involve the entire bone or the patient has previously undergone a partial calcanectomy with recurrence of infection or ulceration, then total calcanectomy is the procedure of choice (32–34). The surgeon should always be prepared to perform a total calcanectomy if one discovers more extensive involvement intraoperatively. As a result, during the preoperative discussion, the patient should be made aware of this possibility. Also total calcanectomy was found to be less stable and resulted in less of a functional foot than partial calcanectomy, which do not interfere with any articulations or joint capsules.

Operative Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree