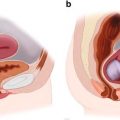

Fig. 17.1

A travel guide to patient-centered geriatric rehabilitation

Meaningful goals anchor geriatric rehabilitation efforts. A shared, collaborative process among providers, patients, families, and their caregivers is mandatory and should result in feasible goals, which are important to the patient. The process of goal setting is arguably more important than any specific objective. If you don’t know where you are going, you are unlikely to get there. The starting point revolves around the patient’s preferences with input from their families and social network. Without this essential buy-in, well-intentioned efforts, as in the example above, have limited chances of success.

A comprehensive geriatric assessment frames the development of goals and the means to achieve them and consists of medical, mental, physical, and environmental domains. For the rehabilitation specialist, the principles of geriatric medicine and common geriatric syndromes represent a necessary starting point is described elsewhere in this chapter in the cross cutting issues of this book. Rehabilitation specialists delve in particular into function. Common domains of assessment of function include physical (e.g., ADLs, mobility, swallowing), cognitive (e.g., memory, judgment, language, and communication), and socio-environmental (housing, barriers social support, and resources). Only by evaluating all these factors can one gain an accurate road map for the “trip.” For example, an individual’s capabilities and potential with ADLs, gait, coping, and cognition within a particular social and physical environment can be pivotal in impacting the ability to live alone, navigate stairs, drive, and manage finances.

The specific treatments of geriatric rehabilitation are the final determinates of a successful arrival at the desired destination and represent the base of the pyramid. Specific treatments include not only the individual activities of a spectrum of rehabilitation professionals such as physical therapy or PT (mobility),occupational therapy or OT (self-care), speech language pathology or SLP (practical cognition), nurses (bladder management) and physicians (symptom management), but recent evidence points to the profound impact of care coordination and team functioning on treatment effectiveness [4]. Higher functioning teams predict improved patient outcomes and staff training interventions were shown to improve patient outcomes in a cluster randomized clinical trial [5]. Recent work to develop process of care measures of team effectiveness is encouraging that such tools could be applicable to Quality Improvement [6]. Process of care measures which capture meaningful interactions between staff and patients hold tremendous potential in the evaluation and improvement of treatment effectiveness, particularly in the relationship oriented areas of rehabilitation and geriatrics.

17.5 Navigating Uncertain Waters of Service Delivery

A common challenge encountered by health care providers is knowing what needs to be done, but an inability to figure out how to get the services in an era of increasing financial constraints. Much has been written about the ballooning health care costs in the USA. The fastest growing expenses for the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are the post acute care (PAC) costs, which includes acute rehabilitation facilities sub-acute (SNF), home health (HH), outpatient therapies, and durable medical equipment (DME). CMS outlays for AC have doubled in the past 14 years. Forty percent of the growth of CMS expenses comes from increasing PAC costs. Understandably, this situation has resulted in close scrutiny of all PACs with subsequent increasing financial and administrative constraints. Ideas under consideration to address this situation include bundling of services and payment neutrality across sites. Under bundling a health care system is paid a lump sum per episode (e.g., hip fracture, stroke, or pneumonia) and has the flexibility to utilize the resources as they deem best. Payment neutrality refers to comparable payments across settings (e.g., sub-acute versus acute rehabilitation).

Many rehabilitation professionals are concerned about the potential deleterious effects of either of these changes primarily through a shift from “acute” rehabilitation to “sub-acute” rehabilitation along with decreasing payments for acute services. Sub-acute services are provided in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) , while acute rehabilitation is provided in acute inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs) . Services in both settings are reimbursed by Medicare, so it is understandable why CMS is keenly interested in the relative cost-effectiveness. Patients treated in sub-acute rehabilitation have longer lengths of stay, lower intensity of services, less physician involvement, and lower per diem costs than patients treated in acute rehabilitation. Physicians with documented rehabilitation expertise, usually in PM&R, manage care in acute settings including daily physician visits and weekly team conferences, while geriatricians or other generalists provide medical oversight in sub-acute settings with a minimum of a monthly visit. Comparisons of outcomes are challenging because of the different, but overlapping patients served and the lack of common functional outcome measures across the two settings. In addition, influential trade organizations for the respected entities advocate for their constituencies creating even more difficulties in meaningful outcome evaluations.

In principle, these settings serve different populations with distinct services. The primary criterion for admission to a sub-acute rehabilitation is a need for skilled level of services, which can be provided by either nursing, PT, or OT. Admission criterion for acute rehabilitation includes the patient’s ability to participate in a minimum of three hours of therapy services a day, justification for two of three rehabilitation therapies (i.e., PT, OT, SLP), and the need for ongoing medical and nursing services. In addition, CMS stipulates that a minimum of 60 % of the patients fall into 1 of 13 diagnostic categories (such as stroke, Parkinson’s disease, or brain injury). Of note, severe debility from a protracted hospitalization and elective joint replacements are not included in one of these categories even though these patients can be admitted within the other 40 % if they meet the other requirements. Hence acute rehabilitation provides more intensive services with greater physician involvement, more effort devoted to care coordination, and shorter lengths of stay at significantly higher per diem costs and total costs.

Practically speaking, this arrangement can be problematic in several ways. A patient may not fit well into any PAC category. For example, a medically complex patient may benefit from daily physician monitoring and proximity to medical specialists found in acute rehabilitation, but not have the physical endurance to tolerate the required intensity of rehabilitation therapies. A medically tenuous patient may not be accepted in acute or sub-acute rehabilitation, and still not meet the criteria for Long Term Acute Care (LTAC) . The wide variations in services and outcomes found in both acute and sub-acute facilities further complicate post acute care discharge planning. It seems that the better the sub-acute facility, the lower chance of a bed availability! These circumstances put the acute hospital discharge planner in an awkward situation as he or she is pressured to take the first available bed. Likewise acute rehabilitation facilities vary in their knowledge and skills in managing the frail, elderly patient. Also, there are patients who would benefit more from the intensity of acute rehabilitation after a period of recuperation and an initial lower intensity of exercise such as acute trauma with activity restrictions or profound debility. However, planned transitions from sub-acute to acute rehabilitation are uncommon and likely due, in part, to financial disincentives for the skilled nursing facility.

An ideal SNF patient could be someone who may not have the endurance to participate in the 3 h a day of therapy, and for whom an extended, slower pace rehabilitation course would likely prove more beneficial. LOS restrictions are more flexible and can extend up to 100 days, provided clinical improvement can be documented under CMS guidelines (though full coverage ends at 3 weeks). An IRF patient would be expected to benefit from a more intense and focused medical, nursing, and rehabilitation therapies, and would be able to achieve desirable goals in a relatively short period of time, such as 2–3 weeks. In general, payors are attracted to the SNF services because of the costs.

An ongoing debate exists in comparing acute versus sub-acute facilities. Discussions on this topic get convoluted as CMS places SNFs, IRFs, LTACs, and Home Health Services (HH) all in the category of post acute care (PAC). For Medicare beneficiaries, services provided in PAC settings are the fastest growing segment of healthcare in the USA. For example, Medicare payments to PAC providers reached $59 billion in 2013, more than doubling the costs since 2001. Faced with concerns on health care costs, CMS has pursued actions under Federal mandates to contain the costs of PACs. For example, IRFs have seen stricter admission criteria, payment cuts, and audit processes to monitor and recoup costs deemed unnecessary or not covered. Concurrent with these constraints has been a steady decline in the number of IRFs. The crux of the discussion is whether and to what extent rehabilitation services can be shifted to less expensive SNF settings.

Comparisons of patient outcomes between acute and sub-acute settings are complicated for a variety of reasons. While the two settings share some similar patients, the populations between the two differ as does the intensity of services, nursing staffing levels, and physician involvement. The two settings use different patient outcomes measurements, and there is tremendous variability among rehabilitation programs. In interpreting analyses between SNF and IRFs, any potential conflict of interests by payors, physician groups, and advocacy groups are salient. The per diem cost of sub-acute rehabilitation is approximately 1/3 to 1/2 of acute rehabilitation, a fact that demands an analysis of clinical quality outcomes in both settings.

With these caveats, there is reasonable evidence that for comparable patients outcomes are superior in acute settings, particularly for the diagnoses of stroke and hip fracture [7, 8]. In a study commissioned by the ARA Research Institute, an affiliate of the American Medical Rehabilitation Providers Association (AMRPA) , Dobson DaVanzo & Associates, LLC examined the impact of the revised classification criterion for IRFs (acute rehabilitation), which were introduced in 2004 [9]. This study was commissioned in an environment of active discussions with CMS and nationally for site-neutral payment proposals and bundling demonstration projects, both of which were felt likely to shift patients from IRFS to SNFs. As an industry sponsored study which has not been published in peer-reviewed journals, readers are advised to examine the methods closely (link listed in reference [9]). With this caveat, the study merits a discussion given its apparent methodological rigor and consistency with findings from other published work.

The study examined over 100,000 matched pairs of patients with the same condition treated between 2005 and 2009 (or 89.6 % of IRF patients and 19.6 % of SNF patients during the study period) with two analyses—cross-sectional and longitudinal. As expected, the cross-sectional analyses found a shift in to IRFs for patients with stroke, brain injury, major medical complexity, neurological disorders, and brain injury and to SNF for patients with elective joint replacements. Compared to the SNF patients, IRF patients had better clinical outcomes on five of six measures in the longitudinal analysis. The sixth measure was hospital readmission and IRF patients had fewer hospital readmissions than SNF patients for amputation, brain injury, hip fracture, major medical complexity, and pain syndrome. See Table 17.1 for one sub-group analysis—hip fracture.

Table 17.1

Comparisons of hip fracture outcomes : acute versus sub-acute rehabilitation*

• 13.3 vs 32.7 days length of stay |

• 8.3 percentage point decrease in mortality rate |

• 55.1 day increase in average days alive |

• 53.1 fewer hospital readmissions per 1000 patients per year |

• 52.8 more days residing at home (2-year period) |

• Cost of $9.77 more per day (2-year period) |

17.6 The Convergence of PM&R and Geriatric Medicine

Rehabilitation is an attitude and an orientation towards the maintenance and promotion of function. In the early to mid-twentieth century, rehabilitation techniques emerged as concerned health care providers addressed functional loss and disability with exercise, wheelchairs, prosthetics, compensatory strategies, and specific medical interventions for disable groups. In the process, a function oriented service delivery model incorporating multidisciplinary interventions within a biopsychosocial framework emerged to optimize a disabled individual’s function. This approach contrasted radically with the traditional medical model at that time of physician dominated authoritative director of health care. This new approach emphasized the interactive role of patients, physicians, and other providers and was a marked departure from the typical model and represented a precursor to the contemporary emphasis on patient-centered care. Like students in school, success is viewed in terms of a skill performance. Can the disabled individual safely bathe, toilet, dress, climb stairs, live alone, or return to work?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree