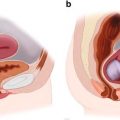

Fig. 14.1

This drawn clock is a fail as there are no numbers in the remaining quadrants, there is only one clock hand, the time is not shown by clock hands, and the numbers 10 11 are out of sequence and not in the right location

- 1.

Draw a clock face on this circle

- 2.

Put in the correct clock numbers (1 through 12 o’clock)

- 3.

Draw the clock hands to show the time of 11:10 AM

The clock draw test is a rapid, inexpensive, and validated screening tool for visuospatial ability in patients suspected of having neurodegenerative disease (e.g., Alzheimer disease) as the cause of their visual complaints. The patients often have no insight into their deficits and may deny having any problem. In this setting the chief complaint might be “Brought in by spouse” or “Can’t read” despite many new glasses & 20/20 OU. Another common visual presentation of visual variant of Alzheimer disease (VVAD) is a homonymous hemianopsia or cortical blindness with reportedly negative neuroimaging (e.g., brain MRI). Careful review of these neuroimaging studies however might reveal subtle posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) in the occipital lobe and visual association cortex corresponding with the homonymous hemianopic field defect. Later the more typical loss of executive function and memory loss will develop but some patients present with visuospatial complaints in the visual variant of Alzheimer’s disease, or PCA. Formal neuropsychologic testing by neuropsychologist consultation might reveal deficits predominantly in visuospatial domains, but also deficits in more typical neurocognitive domains for Alzheimer disease, or may direct attention towards other neurodegenerative disorders.

Visual loss is associated with and may worsen dementia or delirium [115–117]. Dementia can present with visuospatial complaints. The symptoms typically center around visual processing, including getting lost in familiar areas, reading difficulty (despite normal distance and near visual acuity), difficulty with simultaneous (e.g., simultagnosia) or complex visual tasks (e.g., driving), or loss of calculation and visual multitasking abilities. Visuospatial abnormalities present in reading due to the complexity of processing multiple letters in a word, multiple words in a sentence, and multiple sentences in a paragraph. If asked specifically, the patient may agree that they can see the words, but by the time they get to the end of the sentence or paragraph they do not know what they have read, in part from the additional effort it takes just to track along a written phrase. To make matters more complex, pre-existing vision loss may worsen dementia symptoms (loss of visual cues analogous to “sundowning”) and sometimes as in our case vignette, the vision loss may be the presenting or only sign of Alzheimer dementia (i.e., visual variant Alzheimer dementia or PCA).

Reyes-Ortiz et al found that the mini-mental status exam (MMSE-blind) declined more among older Hispanics with near-vision impairment than among those with normal near vision [118]. Anstey et al. reported an association between memory loss over 2 years with vision impairment [119].

In this case, the patient was referred after the abnormal clock draw to cognitive neurology. Formal neuropsychological testing confirmed findings consistent with Alzheimer dementia and treatment was started in the hope of slowing the progression of the dementia. The patient was counseled on the diagnosis and eventually met with the Dean and elected to take retirement.

The patient was also advised to discontinue driving. The task of driving is very complex, and involves not only visual acuity but also visual processing, the cognitive ability to recognize ongoing and simultaneous tasks and challenges (e.g., oncoming traffic, children, animals, and changing visual spatial position of intersecting streets), and the rapidly employed motor response to those tasks. Visual loss can impair the older person’s ability to drive, and legal requirements vary from state to state [7, 20, 120–125]. Unfortunately, decreased Snellen visual acuity is not the only factor for successful driving and other visual factors might impact the ability to drive safely (e.g., dynamic vision, visual processing speed, visual search, light sensitivity, and near vision). Although most states require vision screening for driver’s license renewal, some do not and there is considerable variation in the frequency and level of testing. In cases of cognitive processing deficits, neurology and neuro-psychology consultation are helpful in explaining to the patient and family the need to stop driving.

In one study, elderly patients were five times more likely to have received advice about limiting their driving; four times more likely to report difficulty with challenging driving situations; and two times more likely to reduce their driving exposure. Cataract patients were also found to be 2.5 times more likely to have had an at-fault crash in the prior 5 years. The Useful Field of View test had been validated as a tool to evaluate a patient’s risk of motor vehicle accident while driving; impairment of useful field of view was associated with both self-reported and state-recorded car accidents. In another study, glaucoma was a significant risk factor for state-recorded crashes [123] as were other age-related visual problems [121].

14.3.4 Case Vignette 4

A 70-year-old woman with Fuchs corneal dystrophy and glaucoma presents to her ophthalmologist with a chief complaint of blurred vision OU. The visual acuity is 20/80 OU and she has stable intraocular pressures. She is on treatment with timolol drops OU. She has glaucomatous optic disc cupping at 0.9 OU and stable longstanding glaucomatous nerve fiber layer visual field loss OU. She had prior stable penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) OU with clear corneal grafts OU and she had stable intraocular lenses OU after uncomplicated cataract extraction. The ophthalmologist notes “stable eye exam” in the impression but the patient noted to the ophthalmic technician that she has several recent falls (twice in the last 3 months), once requiring a visit to the emergency department.

Visual loss is an independent risk factor for falling in the elderly. Falls are a common cause of morbidity and mortality in the elderly with up to 25–35 % of older persons suffering a fall [64, 73, 74]. Each year up to 7 % of patients >75 require an emergency room visit after a fall [58–75] and up to 40 % of falls may result in hospitalization [67, 68]. Poor vision is a risk factor for falls [6, 58–74]. Nevitt et al. reported a threefold risk for multiple falls with poor vision [64] and decreased contrast sensitivity, poor depth perception [58] and impaired visual acuity are associated with an increased risk for fracture [60]. In the Beaver Dam Eye Study 11 % (943) of 2365 persons >60 with vision <20/25 had a fall in the prior year compared with only 4.4 % of those with normal visual acuity [6].

We generally recommend an array of potential fall countermeasures for patients and family members to consider including:

Avoiding the use of bifocals, progressive or multifocal lenses in patients with a history of falls, Parkinson disease, downbeat nystagmus, significant inferior visual field defects, or progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP)

increasing lighting and decreasing glare;

increasing contrast at danger areas such as corners and on stair steps;

removing floor obstacles, minimizing clutter, and reducing floor hazards (e.g., anchoring loose rugs and eliminating uneven surfaces); This can be accomplished with an in-home home health evaluation.

utilizing well-designed hand rails and assistive furnishings (e.g., use of non-skid flooring);

using appropriate walking devices (stable walker and cane types);

avoiding improper footwear (e.g., high-heeled shoes) [16].

A number of visual problems have been noted to be associated with falls including: decreased visual acuity, glare, altered depth perception, decreased night vision, and loss of peripheral visual field (including glaucomatous visual field defects). Ophthalmologists should be cognizant of visual loss as a risk factor for falls, as prevention of falling in the elderly is easier and cheaper than dealing with a fall after the fact. One mnemonic device for falls is “I HATE FALLING” (Table 14.1).

Table 14.1

I HATE FALLING mnemonic device

I—Inflammation of joints (or joint deformity) |

H—Hypotension (orthostatic blood pressure changes) |

A—Auditory and visual abnormalities |

T—Tremor (Parkinson’s disease or other causes of tremor) |

E—Equilibrium (balance) |

F—Foot problems |

A—Arrhythmia, heart block, or valvular disease |

L—Leg-length discrepancy |

L—Lack of conditioning (generalized weakness) |

I—Illness |

N—Nutrition (weight loss) |

G—Gait disturbance |

Vision plays an important part in stabilization of posture, and visual impairment may increase the risk for falls independently of environmental hazards. Lord et al found that wearers of multifocal lenses have impaired edge-contrast sensitivity and depth perception, and that the use of multifocals increased the risk of a fall (up to 35 %). In the Blue Mountains Eye Study, the 2-year risk of fractures in patients with visual acuity loss, the visual field deficits, and the presence of posterior subcapsular cataracts were found to be significantly higher than in persons without these findings at baseline.

In addition, correcting visual problems might be an important intervention strategy for elderly persons negotiating stairs and reducing falls.

As vision loss increases the risk for falling in the elderly, ophthalmologists who recognize the risk factor should ask about falls in their older patients, as fall prevention is superior to fall treatment. The importance of preventing the fall cannot be overemphasized. As the fall can lead to an irreversible vicious cascade of events fall → fracture → hospitalization → loss of mobility & independence → nursing home or death. A fall checklist could be given to patients and families for all our vision-impaired elders seen in the ophthalmology clinics. A normal eye exam does not protect patients from falling and can provide a false sense of security to the ophthalmic provider about fall risk in an elderly patient. Even patients such our case vignette with stable eye exams does not necessarily mean that the patient is stable; an eye patient who is stable from an ophthalmic standpoint can still be an unstable patient who is at risk for falls [127–136].

14.3.5 Case Vignette 5

A 75-year-old woman with Alzheimer’s disease is brought in by her pastor for “falling” and hitting her eye. Her son has the power of attorney, but was unable to accompany the patient today. She has periocular ecchymoses, a hyphema, and a retinal detachment OD. She appears disheveled and unkempt and her pastor is concerned about her health. The patient tells you that “she is afraid to go home.” When you call the son regarding your concerns, he tells you to “mind your own business.” The son tells you that he is in charge of his mother and how he treats her is his own business. The pastor feels that she might be neglected or the victim of abuse, and he believes the son might be “taking her Social Security check.”

Elder abuse is an umbrella term that includes the following forms of potential abuse: (1) physical abuse such as inflicting or threatening to inflict harm; (2) sexual abuse such as any non-consensual sexual contact; (3) emotional or psychological abuse either verbal or nonverbal; (4) exploitation both financial or material; (5) neglect, including self-neglect, such as the refusal or failure of care giver to provide appropriate food, shelter, health care, or protection; and (6) abandonment or desertion of a vulnerable elder in time of need.

The requirements for reporting elder abuse differ from state to state, but legislatures in all 50 states have passed some form of elder abuse prevention laws and all of these states have set up reporting systems. Much like child protective services in child abuse, adult protective services (APS) investigates reports of suspected elder abuse and clinicians should be aware of their duty to protect and duty to report such patient abuse http://www.ncea.aoa.gov/library/data/.

Elder abuse is a growing problem that has been increasingly recognized. In one study there was a 19.7 % increase in elder abuse reports from 2000 to 2004 and a 15.6 % increase in substantiated cases from 2000 to 2004. In another study two in five victims (42.8 %) were >80 years http://www.ncea.aoa.gov/library/data. Ophthalmologists should be aware of the risks for their patients and alert for the possibility of exploitation and non-accidental injury in the elderly and the visually impaired.

The take-home messages for ophthalmologists encountering potential elder abuse scenarios include: (1) being aware of the problem of elder abuse and the situations which are suspicious; (2) as in child abuse cases the ophthalmologist should suspect abuse “if story doesn’t match up” especially in unexplained, minor, or implausible trauma; (3) Adult Protective Services is the adult equivalent of Child Protective Services and the same awareness afforded to children should be given to elders; (4) physical abuse is not the only type of elder abuse and clinicians should be aware of; financial, sexual abuse, and neglect are additional forms of abuse, and sometimes the abuse is self-neglect, and should still be reported http://www.ncea.aoa.gov/library/data/.

In summary, the demographic shift in this country will disproportionately affect the specialty of ophthalmology. Geriatric patients are not just “older adults” and have unique responses to disease and special requirements for care. The ACGME competencies provide a potential model for implementation of care guidelines that can promote recognition and treatment of geriatrics syndromes in ophthalmic populations. Ophthalmologists are not expected to be geriatricians, but should be able to recognize, triage, and refer comorbidities in the at-risk elderly patient.

References

1.

Bierman A, Spector W, Atkins D, et al. Improving the Health Care of Older Americans. A Report of the AHRQ task force on aging. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001. AHRQ Publication No. 01-0030.

2.

Bailey IL. New procedures for detecting early vision losses in the elderly. Optom Vis Sci. 1993;70:299–305.PubMed

3.

Castor TD, Carter TL. Low vision: physician screening helps to improve patient function. Geriatrics. 1995;50:51–2. 55–57; quiz 58–59.PubMed

4.

Fletcher DC, Shindell S, Hindman T, Schaffrath M. Low vision rehabilitation. Finding capable people behind damaged eyeballs. West J Med. 1991;154:554–6.PubMedPubMedCentral

5.

Fletcher DC. Low vision: the physician’s role in rehabilitation and referral. Geriatrics. 1994;49:50–3.PubMed

6.

Klein BE, Klein R, Lee KE, Cruickshanks KJ. Performance-based and self-assessed measures of visual function as related to history of falls, hip fractures, and measured gait time. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:160–4.PubMed

7.

Klein R, Klein BE, Linton KL, De Mets DL. The Beaver Dam Eye Study: visual acuity. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1310–5.PubMed

8.

Tielsch JM, Javitt JC, Coleman A, et al. The prevalence of blindness and visual impairment among nursing home residents in Baltimore. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1205–9.PubMed

9.

Tielsch JM, Steinberg EP, Cassard SD, et al. Preoperative functional expectations and postoperative outcomes among patients undergoing first eye cataract surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1312–8.PubMed

10.

American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred Practice Patterns. Cataract in the Adult Eye. 1996.

11.

Applegate WB, Miller ST, Elam JT, et al. Impact of cataract surgery with lens implantation on vision and physical function in elderly patients. JAMA. 1987;257:1064–6.PubMed

12.

Bruce DW, Gray CS. Beyond the cataract: visual and functional disability in elderly people. Age Ageing. 1991;20:389–91.PubMed

13.

Cataract Management Guideline Panel. Clinical Practice Guideline Number 4. Cataract in adults: management of functional impairment. Rockville: Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 1993. AHCPR Pub 93-0542.

14.

Crabtree HL, Hildreth AJ, O’Connell JE, et al. Measuring visual symptoms in British cataract patients: the cataract symptom scale. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:519–23.PubMedPubMedCentral

15.

Javitt JC, Steinberg EP, Sharkey P, et al. Cataract surgery in one eye or both. A billion dollar per year issue. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1583–92. discussion 1592–1583.PubMed

16.

Lee AG, Beaver HA, Teasdale T. The aging eye (CD-ROM). Houston: Baylor College of Medicine; 2001.

17.

Mangione CM, Orav EJ, Lawrence MG, et al. Prediction of visual function after cataract surgery. A prospectively validated model. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1305–11.PubMed

18.

Mangione CM, Phillips RS, Lawrence MG, et al. Improved visual function and attenuation of declines in health-related quality of life after cataract extraction. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:1419–25.PubMed

19.

Monestam E, Wachtmeister L. Impact of cataract surgery on car driving: a population based study in Sweden. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:16–22.PubMedPubMedCentral

20.

Owsley C, Stalvey B, Wells J, Sloane ME. Older drivers and cataract: driving habits and crash risk. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M203–11.PubMed

21.

Powe NR, Schein OD, Gieser SC, et al. Synthesis of the literature on visual acuity and complications following cataract extraction with intraocular lens implantation. Cataract Patient Outcome Research Team. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:239–52.PubMed

22.

Powe NR, Tielsch JM, Schein OD, et al. Rigor of research methods in studies of the effectiveness and safety of cataract extraction with intraocular lens implantation. Cataract Patient Outcome Research Team. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:228–38.PubMed

23.

Schein OD, Steinberg EP, Cassard SD, et al. Predictors of outcome in patients who underwent cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:817–23.PubMed

24.

Schein OD, Bass EB, Sharkey P, et al. Cataract surgical techniques. Preferences and underlying beliefs. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1108–12.PubMed

25.

Steinberg EP, Tielsch JM, Schein OD, et al. National study of cataract surgery outcomes. Variation in 4-month postoperative outcomes as reflected in multiple outcome measures. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1131–40. discussion 1140–1131.PubMed

26.

Steinberg EP, Tielsch JM, Schein OD, et al. The VF-14. An index of functional impairment in patients with cataract. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:630–8.PubMed

27.

Bass EB, Steinberg EP, Luthra R, et al. Do ophthalmologists, anesthesiologists, and internists agree about preoperative testing in healthy patients undergoing cataract surgery? Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1248–56.PubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree