Introduction

The human and economic consequences of avoidable dependency in older people are considerable. This reality was first stated by Marjorie Warren over 60 years ago when she emphasized the need to help sick elderly people to regain their functional independence, the primary elements of which are mobility and independent self-care.1

Older people who typically benefit from rehabilitation will have had a disabling event of recent onset. This is commonly an age-related event such as a stroke, hip fracture, other fall-related injury or deconditioning following a major illness. Many elderly people will have ongoing limitations from other diseases such as osteoarthritis or Parkinson’s disease.

Though there are many reasons why rehabilitation in the old differs from that in the young, perhaps the greatest is the lack of physiological reserve with which to combat a disabling insult. As a consequence, recovery is typically prolonged and the pre-morbid functional state is never fully regained. The specific diseases to which elderly people are susceptible are described throughout this text. This chapter focuses on the process of optimizing recovery from the major disabling diseases of old age and on strategies for adaptation to their long-term sequelae.

Terminology and Classifications

For many years, the World Health Organization (WHO) has sought to classify aspects of health and disease, most notably through its International Classification of Disease, now in its tenth revision (ICD-10).2 Such systems provide a standard language and framework for the description of health and health-related states across geographical boundaries, disciplines and sciences.

To complement the ICD, in 1980 the WHO introduced its International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH).3 This stated that any illness could be considered at three levels: impairment, disability and handicap. In simple terms, impairment refers to the pathological process affecting the person, disability to the resulting loss of function, and handicap to any consequent reduction in that individual’s role in society.

The ICIDH had significant limitations, including the use of pejorative terms that emphasized the negative consequences of ill health and played down its social and societal dimensions. Consequently, in 2001, WHO produced a revised classification, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), which challenged traditional views on health and disability and allowed positive experiences to be described. In particular, the ICF focuses on the impact of the social and physical environment on a person’s functioning.

The ICF contains two parts, each with two components:

Under this classification, each component is further divided into various domains and each domain into a number of categories, which form the units of classification.

The ICF has the following definitions:

Components of the ICF can be expressed in both positive and negative terms. Thus, functioning is an umbrella term for all body functions, activities and participation while disability is a collective term for impairments, activity limitations or participation restrictions.

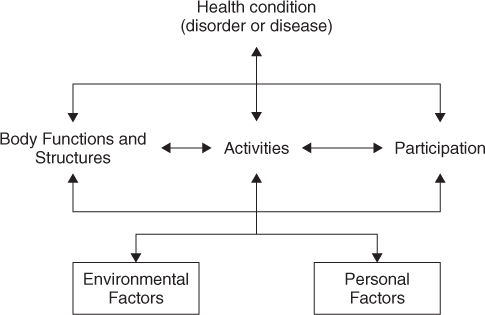

As illustrated by Figure 114.1, an individual’s functioning is a result of a complex interaction between the health condition and contextual factors (i.e. environmental and personal factors). Their interaction is highly dynamic such that any intervention in one area might impact on the other, perhaps in unpredictable ways.

Consider, for example, an individual with Parkinson’s disease, whose impairment (problems in body function or structure) is described elsewhere in this text. As a consequence, the person may have some activity limitations such as difficulty with personal care and mobility. In turn, the person cannot pursue former hobbies and interests (participation restriction), restrictions that might be exacerbated if widowed and living alone in a first floor apartment. Now suppose that she falls and fractures her hip. This new impairment causes her to lose confidence. Further restrictions in activity and participation ensue and she becomes even more isolated, withdrawn and depressed. The feedback loops shown in Figure 114.1 indicate how vicious cycles can develop with the person’s level of activity and participation spiralling downwards.

Simply stated, rehabilitation is a process that seeks to minimize activity and participation restrictions resulting from impairment. Many and more comprehensive definitions exist; perhaps the most widely accepted is the UN definition:5

Rehabilitation means a goal-orientated and time-limited process aimed at enabling an impaired person to reach an optimum mental, physical and/or social functional level, thus providing him or her with the tools to change his or her own life. It can involve measures intended to compensate for a loss of function or a functional limitation (for example the use of technical aids) and other measures intended to facilitate social adjustment or readjustment.

Figure 114.1 also illustrates how rehabilitation programmes can impact at various points in the impairment-activity-participation cycle. Not only can they prevent the progression of impairment to activity restriction and of activity restriction to participation restriction, they can also prevent further impairments and the development of vicious cycles.

Determinants of Activity and Participation Restrictions

As summarized in Table 114.1, many factors determine the activity and participation restrictions that result from a given impairment. The type of impairment is of paramount importance, with some diseases being inherently more likely to cause restrictions than others. The site of a pathological lesion is also important as is well illustrated by stroke disease, where large lesions in some parts of the brain may be asymptomatic while smaller lesions in strategic areas may cause major problems.

Table 114.1 Determinants of activity and participation restrictions.

Determinants of activity restriction Type of impairment (nature and severity of the disease process) Presence of associated impairments Degree of physiological reserve Level of physical fitness Determinants of participation restriction Intrinsic factors Attitude Personality Ability to adjust Cultural issues Extrinsic factors Financial resources Housing Other resources Social supports (spouse, family, neighbours, friends, pets) |

Older patients often have pre-existing impairments contributing to activity and participation restrictions and rehabilitation programmes can be influenced as much by these as by any new impairments.

Regarding reduced physiological reserve, the ageing process is characterized by a gradual functional decline in most bodily systems—a phenomenon which tends to be unimportant when organs and physiological systems are ‘at rest’ but is often critical when they are placed under stress by a disabling illness or event. However, it must be emphasized that even very old people can recover from major illness and failure to make progress at rehabilitation can seldom be attributed to reduced physiological reserve alone. Of far greater importance is the lack of activity and physical fitness that typifies elderly people in modern societies.6 Many of today’s older people grew up in an era when exercise was not encouraged and sports and recreation facilities were relatively inaccessible. An age-related decline in muscle mass (sarcopenia) and strength is aggravated by physical inactivity7 and numerous studies have shown an association between sarcopenia and activity restriction.8

Such age-associated phenomena are reversible. For example, weight training increases muscle strength in older people and improves functional capacity9 and older people who participate in lifelong aerobic or strength training have comparable muscle strength to sedentary middle-aged individuals.10 Although there is little data on the relationship between prior physical fitness and recovery from impairment, it is probable that those who are physically unfit have worse outcomes.

The degree of participation restriction resulting from activity restriction is influenced by several intrinsic and extrinsic factors (Table 114.1). Intrinsic factors include the person’s attitude in adjusting to activity restriction. Somebody who suffers a functional loss typically experiences a grief-like reaction. Some demonstrate better coping strategies than others; they are more positive in their approach, assume greater control of their situation and find solutions to their problems. These issues are discussed in more detail later.

Extrinsic factors that impact on participation include the available resources and supports in dealing with activity restriction. In societies where health and welfare systems are poorly developed, personal finance is required for the many components of a rehabilitation programme. These include the provision of physical therapy, prosthetic devices, home modification and ongoing care. Of even greater importance are the social supports on which the person can rely at all stages of the rehabilitation programme, and particularly upon returning to their former environment. In this regard elderly females are particular disadvantaged, often being widowed and living alone. In Australia, for example, 20% of people aged 65 years and over and 27% of elderly people with activity restriction live alone.11 In recent decades, other demographic trends, such as the loss of the nuclear family and the recruitment of informal carers into paid employment have further reduced the supports available to elderly people.

Psychological Aspects of Rehabilitation

The onset of impairment, particularly if unexpected or catastrophic, is generally associated with some emotional disturbance. Expected feelings include a sense of loss with regard to one’s physical or mental faculties, to relationships with others or to inanimate objects such as one’s home or other possessions. A typical grief reaction involves phases of denial, anger and depression leading to enough acceptance to allow a relatively normal life to be resumed. However, adjustment to impairment is sometimes abnormal. For example, over 40% of older people become depressed following a myocardial infarction and this worsens the prognosis.12 High levels of depression have also been found following stroke,13, 14 despite participation in a rehabilitation programme.15

Some are inherently more adaptable and optimistic than others when faced with an impairment and this greatly influences the development of activity and participation restriction. At one end of the spectrum of responses are ‘highly motivated’ people who set ambitious goals and work hard to achieve them. At the other end are those who submit to their impairment, disengage, surrender power and autonomy and adopt the ‘sick role’.

There are psychological theories to explain such different responses, such as that proposed by Kemp,16 who contends that motivation is a dynamic process driven by four elements: the individual’s wants, beliefs, the rewards to achievement, and the cost to the patient. The first three elements drive motivation in one direction and this is counteracted by the cost in terms of pain and effort. Thus, if a person really wants something, believes it to be attainable and potentially rewarding, he will strive to achieve it, provided the cost is acceptable. The converse also holds. Using this framework, the rehabilitation specialist can help individuals by setting goals, challenging incorrect beliefs, establishing rewards and minimizing the physical and mental cost of the rehabilitation process (cf. section on Psychosocial Support).

Principles of Rehabilitation

The principles of rehabilitation are broadly similar irrespective of the underlying problem and of the working environment. Early intervention is crucial, as avoidable activity and participation restriction can occur soon after the onset of impairment. Problems should be anticipated and avoided as once established, they may prove irremediable. For example, a person with a flaccid hemiplegia is at risk of shoulder subluxation and its long-term sequelae. Proper handling and limb positioning in the immediate post-stroke period will minimize this risk.

A team approach is also essential. A properly resourced team will have input from medical and nursing staff, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech pathologists, clinical psychologists, dieticians and social workers. Doctors are primarily concerned with the assessment and management of impairment while remedial therapists are skilled in managing activity restriction and social workers in managing participation restriction. Nursing staff have an holistic brief with areas of expertise capable of influencing both activity and participation restriction.

To function effectively, team members need to communicate with each another. When they are co-located (e.g. in a designated rehabilitation unit), exchange of information occurs regularly and informally. Most teams also have regular formal meetings to discuss the progress of patients, to revise goals, plan discharge and organize follow-up in the community.

The Rehabilitation Process

The steps in any rehabilitation process are summarized in Table 114.2. Though presented in chronological order, in practice there is considerable overlap between the elements, many of which occur simultaneously and some of which must be regularly revisited. For example, while the assessment of a patient’s impairment, activity and participation restriction is an important initial step, this needs to be repeated frequently (at least weekly) as the rehabilitation programme proceeds.

Table 114.2 Steps in the rehabilitation process.

1 Assessment 2 Setting goals 3 Therapy 4 Aids and adaptations 5 Education 6 Psychological support 7 Evaluation 8 Follow-up |

Assessment

It is essential that patients be assessed before entry into a rehabilitation programme to ensure that their problems are remediable and to determine their optimal management. The selection of patients for rehabilitation can be difficult as it is unfair to subject a person who cannot benefit to a demanding programme and in the process to raise false expectations and waste resources. On the other hand, those who can benefit even to a limited extent should not be denied access.

Assessment should focus on both the problem in the individual and the individual with the problem. The nature and severity of all impairments, whether new or long-standing, should be determined. It is essential to obtain a baseline measure of functional status, so that progress can be monitored and the efficacy of rehabilitation reviewed. A variety of assessment tools are available, ranging from simple subjective measures to the more complex and time consuming. The best choice of tool depends on the clinical context. Busy clinicians can often estimate the extent of activity and participation restriction by asking a few simple questions and by making some equally simple observations. Detailed assessment of activity and participation restrictions using standardized scales is generally left to remedial therapists and social workers.

Assessment of Activity and Activity Restriction

Assessment begins with the clinical history. For the person with a recent impairment, it is important to determine the premorbid as well as the current functional status. A common approach is to focus on activities of daily living (ADLs). These are classified as items of personal care (e.g. washing, grooming, dressing, using toilet, eating, etc.) and those involving the use of ‘instruments’—hence known as instrumental ADLs (IADLs). The latter include such tasks as preparing meals, using the telephone, doing laundry and other housework, gardening, shopping and using public transport. If any difficulties are reported, it is important to determine how the person manages. Are these tasks neglected or do others provide help?

More formal, objective and standardized assessment of activity restriction is generally required when patients are entering a rehabilitation programme. Several assessment scales exist and their strengths and weaknesses have been analysed.17 As yet, there is no consensus on the best assessment scales and a lack of uniformity inhibits comparative research.

The education literature provides a model drawn to explain the difficulty in reaching such a consensus.18 This contends that the utility (U) of any assessment tool is governed by the formula:

where V = validity; R = reliability; A = acceptability and C = cost. While the ideal tool will score highly in the first three areas and be low on cost, in practice, assessment tools with high validity and reliability are invariably costly (i.e. resource intensive) and/or have low acceptability (e.g. are intrusive). The converse is equally true; tools that are easy and cheap to administer often have poor validity and reliability. The multiplication factor in the equation is important, because if any one element of the equation is close to zero, then the overall utility of the assessment tool will also be close to zero. In practice, the utility of any assessment tool is a trade-off between these elements.

Despite these considerations, the UK’s Royal College of Physicians and British Geriatrics Society jointly endorse a number of standardized functional assessment scales for elderly patients, all of which have stood the test of time (Table 114.3). Collectively, they assess competence with activities of daily living, vision, hearing, communication, cognitive function and memory, depression and quality of life.27

Table 114.3 Standardized functional assessment scales for elderly patients.

| Domain assessed | Recommended scale | Comments |

| Basic activities of daily living (ADL) | Barthel Index19, 20 | Observation of what the patient does. Ceiling effect in ambulatory patients. |

| Vision, Hearing, Communication | Lambeth Disability Screening Questionnaire21 | Postal questionnaire |

| Memory and Cognitive Function | Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT)22, 23 | 10 questions from longer Roth-Hopkins test |

| Depression | Geriatric Depression Scale24 | Screening test with 30 questions; 15 questions in short form25 |

| Subjective morale | Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale26 | Distinct from depression, although some overlap |

Reproduced from Royal College of Physicians and British Geriatrics Society Joint Workshops (1992), 27 with permission.

Such standardized scales facilitate the exchange of information across acute, rehabilitation and community-based healthcare settings. They allow the effectiveness of rehabilitation to be measured and foster comparisons of different approaches to treatment. Standardized assessments can also minimize the repeated gathering of identical information by the various members of multidisciplinary rehabilitation teams.

Other assessment scales deserve special consideration. Neurodegenerative disorders are common in older patients and Wade has provided a valuable reference for commonly used assessment measures in neurological rehabilitation.28 A drive towards output-driven health funding in many countries has stimulated the development of specific outcome measures in rehabilitation. The Functional Independence Measure (FIM) scores patient progress in 18 common functions concerning self-care, sphincter control, mobility, locomotion, communication and social cognition.29 Attempts have been made to use the FIM to identify the most effective and efficient aspects of rehabilitation programmes.30, 31

Assessment of Participation and Participation Restriction

As individuals uniquely interact with their environment, so any reduced role in society (participation restriction) resulting from activity restriction will be unique to the individual. Furthermore, it is possible for somebody to develop major participation restriction in one area and have little or no restriction in another. Thus, the person who loses mobility following a lower limb amputation may no longer be able to play golf but can continue to drive a car. As explained earlier, the level of participation restriction is mainly determined by one’s ability to adapt. While some fail in this regard, for others the onset of activity restriction prompts a redefinition rather than a loss of social role. Potential losses in one area can be offset by gains elsewhere, thus minimizing participation restriction. The authors occasionally encounter people who consider their lives to have been enriched through developing an impairment and associated activity restriction.

It follows that an assessment of participation restriction can only be obtained through gaining an in-depth understanding of the individual and the manner in which he or she has come to terms with activity restriction. Such measurements are always subjective. They are also unstable over time and can be influenced by psycho-behavioural variables such as mood. For these reasons the assessment of participation restriction is largely neglected in both clinical and research settings.

Goal Setting

Assessment should culminate in the setting of rehabilitation goals. To avoid frustration and disappointment for all concerned, goals should be realistic and take account of the individual’s impairment and pre-morbid functional status. It is sometimes appropriate to set modest goals, such as helping an amputee patient to become wheelchair-independent rather than to walk. It is essential that all multidisciplinary team members, and particularly the patient, are involved in setting goals and that there is general agreement on the validity of the set targets.32 A programme can be seriously compromised if key people differ on what each is trying to achieve. Patients with ambitious goals seem to make greater progress than those with more modest targets;33 a pragmatic approach is to set ambitious but achievable goals.

Short-term (intermediate) as well as long-term (final) goals should be identified; by achieving a succession of intermediate goals, the patient arrives at the final goal. It is important to set realistic time frames for the achievement of goals, bearing in mind that the rate of progress can be difficult to predict, particularly at the outset. Goals and time frames should therefore be flexible, be regularly reviewed and modified when necessary.

Therapy

A detailed description of the role of the various multidisciplinary rehabilitation team members is outside the scope of this chapter. In brief, doctors focus on the identification and management of the presenting problem and coexisting impairments. Underlying risk factors are identified and minimized; potential complications are anticipated and prevented. Thus, in an arteriopath who has had an embolic stroke, the doctor monitors anticoagulation, controls hypertension and manages coexisting angina pectoris and diabetes mellitus. Occupational therapists (OTs) assess and enhance competence with activities of daily living. Physiotherapists provide therapies that target specific problems and enhance cardiorespiratory, neuromuscular and locomotor function. Speech and Language Therapists deal with communication issues and swallowing disorders. In specific situation, input from other health professionals (e.g. clinical psychologists, podiatrists, dieticians) may be invaluable.

Aids and Adaptations

The use of aids has the potential to reduce activity and participation restriction for many impaired people. Devices range from the simple and inexpensive to the technologically advanced. They help people in diverse ways, from carrying out activities of daily living to the maintenance of mobility and the promotion of continence. The most commonly used aids have been critiqued by Mulley.34 The provision of an aid is not always the best option for an impaired person as it can foster dependence rather than independence. However, those in real need often do not avail of even basic and aids and appliances.35

Advice on the suitability of aids is best left to OTs or others with particular expertise. Physiotherapists can advise on mobility aids, speech therapists on communication aids, audiologists on hearing aids and continence advisors on continence aids. Such people can also provide follow-up and ensure that aids are properly used and maintained and continue to serve their purpose.

The design, construction and fitting of prostheses (devices which replace body parts) and orthoses (devices applied to the external surface of the body to provide support, improve function, or restrict or promote movement) require particular skill and technological expertise. Well-resourced rehabilitation centres have access to prosthetists and orthotists as part of the multidisciplinary team.

Adapting the home environment also promotes activity and participation. This might include the installation of simple handrails or ramps, or improving access to shower and toilet areas. Early input from an OT, often including a home visit, ensures that modifications will be appropriate and timed to facilitate hospital discharge.

Education and Secondary Prevention

Education is a vital part of rehabilitation, as it empowers the patient to minimize the activity and participation restrictions that result from impairment. The unique educational needs (in terms of knowledge, skills and attitudes) of the individual must first be determined and the patient has a central role in setting the agenda. A compromise must be reached when there is a discrepancy between the person’s perceived needs and actual needs (as determined by health professionals).

Generally, patients need to learn about their impairment, its aetiology, underlying risk factors, management and prognosis. This fosters compliance with treatment and impacts on attitudes. The skills required will be highly specific and can range from cognitive skills to the more practical manual skills. Patients who are empowered through education are more likely to assume responsibility for their health and to institute life changes to maintain it.

Education should be integrated into all stages of the rehabilitation programme through informal daily contact with team members. Formal educational activities can complement the more informal. These can occur on an individual basis or in group settings. The format can vary from the distribution of educational literature to didactic presentations and small group discussions. Discussion groups allow patients to learn from one another and provide mutual support and encouragement.

Psychosocial Support

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree