Chapter Outline

Reference ranges 8

Statistical procedures 9

Confidence limits 9

Normal reference values 10

Physiological variations in the blood count 13

Effects of smoking on haematological normal reference values 16

A number of factors affect haematological values in apparently healthy individuals. As described in Chapter 1 , these include the technique and timing of blood collection, the transport and storage of specimens, the posture of the subject when the sample is taken, the prior physical activity and the degree of ambulation (e.g. whether the subject is confined to bed or not). Variation in the analytical methods used may also affect the measurements. These can all be standardised.

More problematic are the inherent variables as a result of gender, age, occupation, body build, genetic background and adaptation to diet and to environment (especially altitude). These factors must be recognised when establishing physiologically normal values. It is also difficult to be certain that the ‘normal’ subjects used for constructing normal ranges are completely healthy and do not have nutritional deficiencies, mild chronic infections, parasitic infestations or the effects of smoking.

Haematological values for the normal and abnormal will overlap and a value within the recognised normal range may be definitely pathological in a particular subject. For these reasons the concept of ‘normal values’ and ‘normal ranges’ has been replaced by reference values and the reference range, which is defined by reference limits and obtained from measurements on the reference population for a particular test. Unless a reference range is derived in this manner, the term should not be used. The reference range is also termed the reference interval. , Ideally, each laboratory should establish a databank of reference values that takes account of the variables mentioned earlier and the test method, so that an individual’s result can be expressed and interpreted relative to a comparable apparently normal population, insofar as normal can be defined.

New haematological parameters such as the number of immature cells or the number of red cell fragments are often initially developed for research purposes but can be used for clinical decision making once internal quality control and external quality assessment processes are in place.

Reference ranges

A reference range for a specified population can be established from measurements on a relatively small number of subjects (discussed later) if they are assumed to be representative of the population as a whole. The conditions for obtaining samples from the individuals and the analytical procedures must be standardised, whereas data should be analysed separately for different variables relating to individuals – recumbent or ambulant, smokers or nonsmokers and so on. One approach is that specimens are collected at about the same time of day, preferably in the morning before breakfast; the last meal should have been eaten no later than 9 p.m. on the previous evening, and at that time alcohol should have been restricted to one bottle of beer or an equivalent amount of another alcoholic drink. An alternative approach is that, unless a test is usually done on a fasting patient, specimens are collected throughout the day on subjects who are not fasting or resting, as this will produce a reference range that is more relevant to results from patients. It is sometimes appropriate that the reference population is defined as having normal results for specific laboratory tests. For example, if determining a reference range for blood count components it may be necessary, in some populations, to exclude iron deficiency, β thalassaemia heterozygosity and, when relevant, α thalassaemia.

Statistical procedures

In biological measurements, it is usually assumed that the data will fit a specified type of pattern, either symmetric (Gaussian) or asymmetric with a skewed distribution (non-Gaussian). With a Gaussian distribution, the arithmetic mean ( ![]() ) can be obtained by dividing the sum of all measurements by the number of observations. The mode is the value that occurs most frequently and the median (m) is the point at which there are an equal number of observations above and below it. In a true Gaussian distribution they should all be the same. The standard deviation (SD) can be calculated as described on page 565.

) can be obtained by dividing the sum of all measurements by the number of observations. The mode is the value that occurs most frequently and the median (m) is the point at which there are an equal number of observations above and below it. In a true Gaussian distribution they should all be the same. The standard deviation (SD) can be calculated as described on page 565.

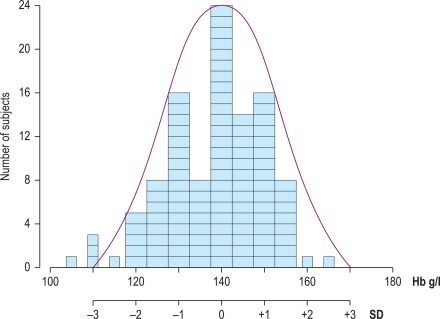

If the data fit a Gaussian distribution, when plotted as a frequency histogram the pattern shown in Figure 2-1 is obtained. Taking the mode and the calculated SD as reference points, a Gaussian curve is superimposed on the histogram. From this curve, practical reference limits can be determined even if the original histogram included outlying results from some subjects not belonging to the normal population. Limits representing the 95% reference range are calculated from the arithmetic mean ± 2SD (or more accurately ± 1.96SD).

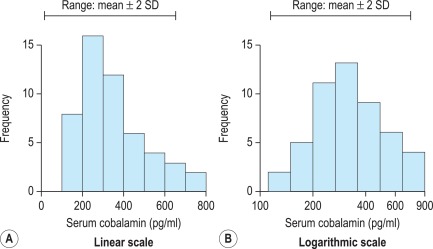

When there is a log normal (skewed) distribution of measurements, the range to − 2SD may even extend to zero ( Fig. 2-2 , A ). To avoid this anomaly, the data should be plotted on semilogarithmic graph paper to obtain a normal distribution histogram ( Fig. 2-2 , B ). To calculate the mean and SD the data should be converted to their logarithms. The log–mean value is obtained by adding the logs of all the measurements and dividing by the number of observations. The log SD is calculated by the formula on page 566 and the results are then converted to their antilogs to express the data in the arithmetic scale. This process is now generally carried out using an appropriate statistical computer program.

When it is not possible to make an assumption about the type of distribution, a nonparametric procedure may be used instead to obtain the median and SD. To obtain an approximation of the SD, the range that comprises the middle 50% spread (i.e. between 25 and 75% of results) is read and divided by 1.35. This represents 1SD.

Confidence limits

In any of the methods of analysis, a reasonably reliable estimate can be obtained with 40 values, although a larger number (≥ 120) is preferable ( Fig. 2-3 ). When a large set of reference values is unattainable and precise estimation is impossible, a smaller number of values may still serve as a useful clinical guide. Confidence limits define the reliability (e.g. 95% or 99%) of the established reference values when assessing the significance of a test result, especially when it is on the borderline between normal and abnormal. Calculation of confidence limits is described on page 566. Another important measurement is the coefficient of variation (CV) of the test because a wide CV is likely to influence its clinical utility (see p. 566 ).

Normal reference values

The data given in Tables 2-1, 2-2 and 2-3 provide general guidance to normal reference values that are applicable to most healthy adults and children in high-income countries. However, slightly different ranges may be found in individual laboratories where different analysers and methods are used. The reference interval, which comprises a range of ± 2SD from the mean, indicates the limits that should cover 95% of normal subjects; 99% of normal subjects will be included in a range of ± 3SD. Age and gender differences have been taken into account for some values. Even so, the wide ranges that are shown for some tests reflect the influence of various factors, as described below. Narrower ranges would be expected under standardised conditions. Because modern analysers provide a high level of technical precision, even small differences in successive measurements may be significant. It is thus important to establish and understand the limits of physiological variation for various tests. The blood count data and other test results can then provide sensitive indications of minor abnormalities that may be important in clinical interpretation and health screening.

| Red blood cell count | |

| Men | 5.0 ± 0.5 × 10 12 /l |

| Women | 4.3 ± 0.5 × 10 12 /l |

| Haemoglobin concentration * | |

| Men | 150 ± 20 g/l |

| Women | 135 ± 15 g/l |

| Packed cell volume (PCV) or haematocrit (Hct) | |

| Men | 0.45 ± 0.05 l/l |

| Women | 0.41 ± 0.05 l/l |

| Mean cell volume (MCV) | |

| Men and women | 92 ± 9 fl |

| Mean cell haemoglobin (MCH) | |

| Men and women | 29.5 ± 2.5 pg |

| Mean cell haemoglobin concentration (MCHC) | |

| Men and women | 330 ± 15 g/l |

| Red cell distribution width (RDW) | |

| As coefficient of variation (CV) | 12.8% ± 1.2% |

| Red cell diameter (mean values) | |

| Dry films | 6.7–7.7 μm |

| Red cell density | 1092–1100 g/l |

| Reticulocyte count | 50–100 × 10 9 /l (0.5–2.5%) |

| White blood cell count | 4.0–10.0 × 10 9 /l |

| Differential white cell count | |

| Neutrophils | 2.0–7.0 × 10 9 /l (40–80%) |

| Lymphocytes | 1.0–3.0 × 10 9 /l (20–40%) |

| Monocytes | 0.2–1.0 × 10 9 /l (2–10%) |

| Eosinophils | 0.02–0.5 × 10 9 /l (1–6%) |

| Basophils | 0.02–0.1 × 10 9 /l (< 1–2%) |

| Lymphocyte subsets (approximations from ranges in published data) | |

| CD3 | 0.6–2.5 × 10 9 /l (60–85%) |

| CD4 | 0.4–1.5 × 10 9 /l (30–50%) |

| CD8 | 0.2–1.1 × 10 9 /l (10–35%) |

| CD4/CD8 ratio | 0.7–3.5 |

| Platelet count | 280 ± 130 × 10 9 /l |

| Bleeding time † | |

| Ivy method | 2–7 min |

| Template method | 2.5–9.5 min |

| Thrombin time | 15–19 s |

| Plasma fibrinogen concentration | 1.8–3.6 g/l |

| Plasminogen concentration ‡ | 0.75–1.60 u/ml |

| Antithrombin concentration ‡ | 0.75–1.25 u/ml |

| Protein C concentration ‡ | |

| Functional | 0.70–1.40 u/ml |

| Antigen | 0.61–1.32 u/ml |

| Protein S concentration ‡ | |

| Total antigen | 0.78–1.37 u/ml |

| Free antigen | 0.68–1.52 u/ml |

| Premenopausal women § | 0.55–1.55 u/ml |

| Functional | 0.60–1.35 u/ml |

| Premenopausal women | 0.55–1.35 u/ml |

| Heparin cofactor II concentration ‡ | 0.55–1.45 u/ml |

| Median red cell fragility (MCF) (g/l NaCl) | |

| Fresh blood | 4.0–4.45 g/l NaCl |

| After 24 h at 37 °C | 4.65–5.9 g/l NaCl |

| Cold agglutinin titre (4 °C) | < 64 |

| Blood volume (normalised to ‘ideal weight’) | |

| Red cell volume | |

| Men | 30 ± 5 ml/kg |

| Women | 25 ± 5 ml/kg |

| Plasma volume | 45 ± 5 ml/kg |

| Total blood volume | 70 ± 10 ml/kg |

| Red cell lifespan | 120 ± 30 days |

| Serum iron | |

| Men and women | 10–30 μmol/l (0.6–1.7 mg/l) |

| Total iron-binding capacity | 47–70 μmol/l (2.5–4.0 mg/l) |

| Transferrin saturation | 16–50% |

| Serum ferritin concentration | |

| Men | 15–300 μg/l (median 100 μg/l) |

| Women | 15–200 μg/l (median 40 μg/l) |

| Serum vitamin B 12 concentration | 180–640 ng/l |

| Serum folate concentration | 3–20 μg/l (6.8–45 nmol/l) |

| Red cell folate concentration | 160–640 μg/l (0.36–1.45 μmol/l) |

| Plasma haemoglobin concentration | 10–40 mg/l |

| Serum haptoglobin concentration | |

| Radial immunodiffusion | 0.8–2.7 g/l |

| Haemoglobin binding capacity | 0.3–2.0 g/l |

| Haemoglobin A 2 | 2.2–3.5% |

| Haemoglobin F | < 1.0% |

| Methaemoglobin | < 2.0% |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm in 1 h at 20 ± 3 °C) | |

| Men | |

| 17–50 years | ≤ 10 |

| 51–60 years | ≤ 12 |

| 61–70 years | ≤ 14 |

| > 70 years | ≤ 30 |

| Women | |

| 17–50 years | ≤ 12 |

| 51–60 years | ≤ 19 |

| 61–70 years | ≤ 20 |

| > 70 years | ≤ 35 |

| Plasma viscosity | |

| 25 °C | 1.50–1.72 mPa/s |

| 37 °C | 1.16–1.33 mPa/s |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree