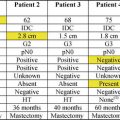

Fig. 20.1

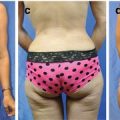

(a–c) Inflammatory breast cancer of the right breast: chest wall reconstruction with extended DIEP flap 25 × 25 cm; abdominal donor site closed with V-Y advanced DIEP flap from the right side of the abdomen

Epidemiology

LABC represents 5–20 % of all breast cancer in developed countries. While the incidence is decreasing in mammographically screened populations (less than 5 % of those in the United States), LABC cases represent up to 40–50 % of new cases in underdeveloped countries. The incidence also appears to be higher in younger women and African-American and Hispanic women. In contrast, inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) represents 0.5–2 % of cases in the United States. However, it appears to be increasing in incidence, particularly in white women. It is important to note that the incidence of IBC remains higher in African-Americans. It also tends to be diagnosed at an earlier age (median 59 vs. 66) as compared to LABC [1–3].

Treatment

Although the specific treatment options are too in-depth for discussion here, some important aspects of treatment for LABC are useful to keep in mind. In general, the treatment of LABC utilizes multimodality therapy that includes systemic chemotherapy, either in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting, and locoregional therapy with radiation. As radiation therapy is the standard in the multimodal treatment of LABC and IBC, special attention must be given to its physiologic side effects on the breast. The mechanism of injury may involve vaso-occlusive processes as well as chromosomal alterations in fibroblasts that result in dysfunctional collagen formation [4, 5]. These physiologic aberrations result in markedly increased complication rates after radiation treatment in patients treated primarily with mastectomy. One study cites an institutional complication rate (including wound infections, dehiscence, and necrosis) in up to 50 % of mastectomy patients and 30–87 % of chest wall reconstruction patients previously treated with postoperative radiation [6–9].

The reconstructive surgeon must be prepared to excise much of the irradiated tissue, which can result in a much larger defect than anticipated. Local tissue may often be inadequate because of radiation damage and microsurgical efforts may be complicated by alterations in the wound bed, as well as recipient vessels. As a result, donor tissue must be well outside of the irradiated fields to ensure the greatest potential for flap survival.

Chest Wall Reconstruction

Patients with LABC without evidence of distant metastasis can undergo operative treatment with curative intent. The goals of chest wall reconstruction in LABC patients are to alleviate symptoms, to enhance quality of life, and to cover vital structures. Several options are available for chest wall reconstruction, with multiple factors to consider before any particular case. Some of these factors are the patient’s desire, outcome, and willingness to undergo multiple (often lengthy) procedures and extended hospital stays. Physiologic factors that impact operative strategy include size, composition of the defect, quality of donor and recipient tissues, and the effects of radiation as described above.

Skin Grafting

Although much discussion has been given to the “reconstructive ladder” and after primary closure, the next “simplest” option for chest wall reconstruction is placement of a split-thickness skin graft (STSG). The STSG is only an option, however, when the defect is limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissue. When skin grafts are applied to irradiated tissue, they may not “take” as skin grafts rely on recipient beds for their blood supply. Skin grafting is also the least aesthetically acceptable option of all options for chest wall reconstruction, but it remains a valuable adjunct for coverage of muscle flaps employed in larger defects. The muscle flap that has not been irradiated is an acceptable recipient site for STSG.

Flaps

Local Flaps

Local flaps can be employed for the coverage of smaller defects of the chest wall. The limitation of local flaps is the dependence on the quality of the surrounding tissue. Local flaps are often excluded from use because of the effects of radiation, the size of flap available, and their limited utility in chest wall reconstruction for LABC.

Regional Flaps

As previously stated, LABC typically requires extensive resection of tissue and causes large defects. Myocutaneous flaps are the most commonly employed approach, since these flaps provide enough bulk and coverage for large defects of the chest wall.

Latissimus Dorsi Flap

The latissimus dorsi flap is one of the most commonly used flaps for chest wall reconstruction for LABC. A class V muscle flap with a dominant pedicle (the thoracodorsal artery and vein) and a secondary blood supply (the posterior intercostal perforators), the latissimus flap was first described by Tansini in 1897 for chest wall reconstruction. Over the years, multiple revisions and improvements in harvesting techniques have led the latissimus flap to become one of the most versatile flaps in all of plastic surgery.

The latissimus dorsi flap has several benefits. The dissection is rapid, relatively straightforward, and safe. The muscle has a long pedicle that facilitates local transfer as a pedicle-based flap or as a microvascular free tissue transfer. A skin island can be oriented in virtually any direction, and its proximity to the chest makes it ideal for breast reconstruction. Disadvantages of the flap are few, but not insignificant. The width of the traditional elliptical skin island cannot exceed 9–10 cm or the donor site cannot be closed primarily. For large defects, a skin graft will be needed to cover the exposed portions of the muscle. A modification of the traditional skin pattern by Micali and Carramaschi described below allows for a larger skin island.

Many of the disadvantages are related to donor site morbidity. Seroma formation after latissimus dorsi harvest has been reported to have an incidence of anywhere between 4 % and 80 % of patients [10]. Dynamic testing has shown that there is a decrease in strength in the affected extremity after latissimus dorsi muscle transfer [11]. That effect appears to be greater in women than in men [12]. While this decrease in strength has not been shown to affect normal daily activities, special consideration must be given to patients with increased reliance on shoulder girdle strength, such as those who are walker dependent. While radiation to the axilla or previous axillary dissection is not a contraindication to latissimus dorsi flap utilization, one must keep in mind that the vascular supply may be compromised in irradiated fields or disrupted by axillary dissection.

A modification of the latissimus dorsi flap has been described by Micali and Carramaschi [13]. They describe what they refer to as an extended V-Y musculocutaneous flap; the primary benefits include decrease in the morbidity of the donor site and ability to close the donor site primarily. The skin island of this flap is a large triangle, with its base along the chest wall defect (in the case of mastectomy, the posterior-lateral resection edge). The apex of the flap is at the midline of the back, and the flap is situated over musculocutaneous perforators that emerge from the underlying latissimus dorsi muscle.

The large triangular skin flap is incised circumferentially down to the underlying latissimus flap. The skin of the back is then elevated above the latissimus muscle until the entire muscle outer surface is exposed. The muscle is then harvested in the normal manner, based on the thoracodorsal circulation. Once freed from its origin and insertion, the flap will easily move into the chest defect, carrying the large skin island (as much as 22 cm in width and 42 cm in length). The donor site is closed as a V-Y [10]. Fierreira, Mendoca, et al. reported a series of 25 patients with excellent outcomes [14] (Figs. 20.2 and 20.3).

Fig. 20.2

The latissimus musculocutaneous V-Y rotational flap

Fig. 20.3

Mastectomy patient with large wound closed with V-Y latissimus myocutaneous flap. (a) Locally advanced breast cancer with involved skin (b) defect after resection (c) latissimus advanced with overlying skin in V-Y fashion (d) final result

Rectus Abdominis Flaps

Rectus abdominis flaps have been a mainstay of reconstructive surgery for nearly 50 years. Like the latissimus dorsi flap, the rectus abdominis flap has the benefit of relative ease of elevation, reliable vascular pedicle (arising from the superior and deep inferior epigastric arteries), and a large amount of tissue available for harvest. The collateral circulation between these vessels allows the rectus to be oriented in a variety of configurations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree