Chapter 19

Putting the Pieces Together to Make Difficult Decisions

You climb a mountain, edging slowly upwards.

Rock by rock,

step by step, one at a time.

From one point to another up the mountain.

From one height achieved to another.

—ANONYMOUS

KNOWING YOU’RE PREDISPOSED TO CANCER may not make your decisions easier, because without ideal ways to prevent or cure it, our current options are imperfect. Take your risk seriously, yet understand you can do something about it. Consider the short- and long-term outcomes for each alternative, and realize that your future decisions may be different from the ones you make now.

Deciding what to do can be agonizing. Is reliable early detection for ovarian cancer just a year away? Can you afford to wait to have your ovaries removed? Making complex decisions like these may seem like choosing the lesser of two (or three or four) evils. Even though you probably prefer none of them, knowing all your options allows you to consider each and choose the one that is best for you. While you may feel a sense of urgency to make a choice, you may also be fearful to proceed. How do you weigh all the options and consequences and choose effective decisions that you can live with? You do it one step at a time.

Start at the Beginning: Should You Be Tested?

Influenced by their family history, some people want to be tested for a BRCA mutation immediately. Others don’t. If you’re a candidate for genetic testing, but your fear of a positive result is holding you back, remember that many people test negative. And although facing the implications of a positive test is difficult, it provides the opportunity to be proactive. Regardless of your initial feelings, it’s important to base your decisions on credible and up-to-date information. Your first step should be a consultation with a qualified genetics expert.

Making Decisions to Reduce Your Risk

Your priorities and tolerance for risk shape your decisions, which may not be the same as someone else in your situation. If you’re a previvor in your twenties who wants to become pregnant within two years, you might choose preventive mastectomy before your pregnancy, particularly if you’ve seen young-onset breast cancer in your family. It not only reduces your risk, it eliminates the need for surveillance during pregnancy. If you feel strongly about breastfeeding, you may prefer surveillance. Whether you’re a previvor or survivor, whatever you decide must be right for you. As you weigh your alternatives, you’ll want to address two important outcomes: risk reduction and long-term survival.

Addressing Survival

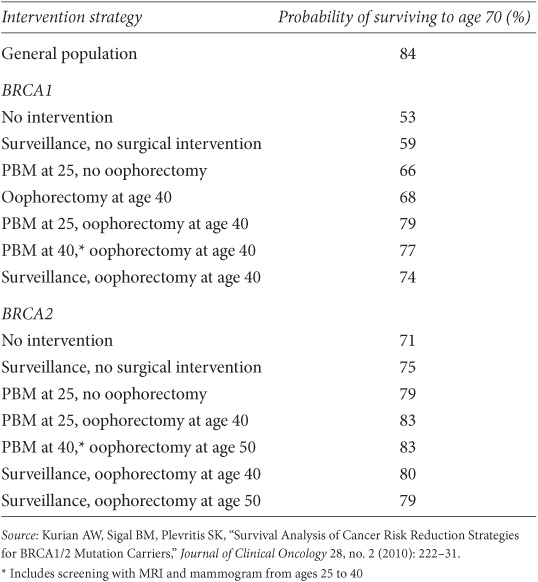

If you have a BRCA mutation, breast and ovarian cancer pose a double threat. A Stanford University mathematical model projects how surveillance and preventive surgery affect survival in previvors. The model doesn’t assume that one option provides better quality of life than another (for example, preventive mastectomy versus breast surveillance), since that’s a subjective measurement. Instead, it offers information about the likely outcomes of both strategies, allowing women to rank options according to their own values. Chemoprevention alternatives aren’t included in this analysis, because no conclusive evidence shows they affect life expectancy. The model does address the impact of young menopause (heart disease, osteoporosis/fractures, and dementia) on the risk of dying. The model doesn’t assume routine use of hormone therapy after menopause, which might change the estimated benefit from preventive surgeries, or the impact of early menopause on survival (see table 20).

According to the model, mastectomy at age 25 and oophorectomy at age 40 lead to the greatest survival gains for carriers of a BRCA1 mutation. Increased breast surveillance (mammography and MRI screenings every year) combined with oophorectomy produces somewhat lower but similar results, because most breast cancers would likely be caught early enough to be treated successfully. The single most effective action is oophorectomy at or before age 40. Without any intervention, survival is projected to be considerably lower than for women in the general population.

If you have a mutation in BRCA2, survival estimates are more favorable, because your risk of gynecologic cancers is lower than that of someone with a BRCA1 mutation. Mastectomy at age 25 and oophorectomy at age 40 bring your estimated risk almost to the level of women who don’t have a mutation. The model predicts a similar probability of survival for BRCA2 mutation carriers who delay mastectomy from age 25 until age 40 and delay oophorectomy from age 40 until age 50, because of the relatively low ovarian cancer risk they have before age 50.

Table 20. Effects of projected risk-reducing interventions

Statistics help us make decisions; they don’t guarantee the future. Your own survival outcome may be better or worse than these predictions. For now, the model is the most sophisticated survival tool available. It estimates cancer and survival in BRCA mutation carriers based on different strategies and may be helpful in your overall decision making, but keep in mind what it doesn’t do. It doesn’t factor in complex variables that might affect mortality or quality of life in people with BRCA mutations. Delaying preventive actions significantly affects your likelihood of being diagnosed with cancer.

Preventing Breast Cancer

People often make risk-reducing decisions based on whether a particular action will decrease their risk of dying from cancer. That’s certainly important and something we’re all very interested in. If you’re at high risk for hereditary cancer, you may be equally concerned about avoiding diagnosis and treatment and how your risk-reducing decisions may affect your quality of life. If you’d rather avoid radiation or chemotherapy to treat breast cancer, even though you’re likely to survive (as most women do), you may want to consider preventive mastectomy—it most effectively lowers the risk for a breast cancer diagnosis.

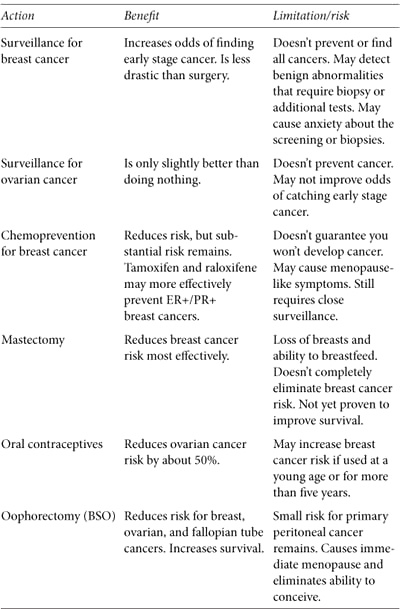

Comparing Your Options

As you weigh the options before you, use table 21 to consider ways to manage your risk. List additional advantages and disadvantages of these alternatives that affect you. Every concern you have is valid, no matter how small. You might be interested in a particular breast reconstructive procedure for which you must travel to another city. That choice may represent a definite disadvantage if you can’t afford the associated expense or have no one to care for your children when you’re away or recovering. Work your way through all of your options, one by one, and be sure to discuss the medical benefits and risks with your healthcare team to ensure you’ve considered all possibilities. Then prioritize the list, eliminating unacceptable actions (see table 22).

Table 21. Comparing risk-reducing alternatives

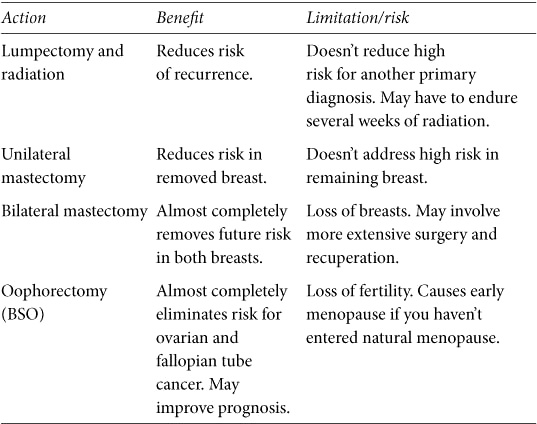

Table 22. Comparing treatment alternatives

Making Decisions about Treatment

Even two women with the same diagnosis may make different decisions about genetic testing and surgery. Diagnosed with breast cancer, one may feel it’s wiser to be tested before surgery; that way, if she has a BRCA mutation, she might choose bilateral mastectomy to address her risk for a future breast cancer. If her test result is negative, she might proceed with a lumpectomy. A second woman, fearing even a week’s delay in treatment, may decide to forego genetic testing and have a lumpectomy as quickly as possible rather than delaying surgery to wait for BRCA test results.

From Confused to Clear in Fifteen Steps

Genetic testing. Cancer risk. Preventive medications and surgeries. Fertility. These issues can be overwhelming, and you may think there’s no light at the end of the tunnel. The key is to create order when your life may seem to be spinning out of control. Then that light will seem brighter and a lot more attainable.

1. Assemble your healthcare team, making sure each member is aware of what the others recommend.

2. Keep an organized binder of all your medical records, test results, research, and documents related to your previvor or survivor status.

3. Learn all you can about your absolute and relative risk, high-risk status, risk management options, or diagnosis and treatment alternatives.

4. Write down your questions and get answers.

5. Know when to stop researching: when you have all the information you can absorb and need to decide.

6. Recruit your family or friends to help research and provide a fresh perspective.

7. Allow yourself time to let it all sink in.

8. Give yourself a break. Take time to get away from information overload.

9. Take care of yourself. Eat balanced meals and get some physical activity most days.

10. Weigh the benefits and limitations of choosing or rejecting each option.

11. Consult the most knowledgeable professionals you can find for each decision.

12. Make your risk management or treatment decisions.

13. Cry or vent if you need to. (It’s okay!)

14. Speak with a mental healthcare professional if you need help dealing with emotional stress.

15. Share. You don’t have to face these issues alone. Reach out anytime to FORCE in a way that is most comfortable for you: online (www.facingourrisk.org), through our helpline (866-288-7475), or in person at your local FORCE outreach group. We can help put you in touch with someone who went through similar decisions based on age, childbearing, cancer diagnosis, and other factors like your own.

MY STORY: My Family’s Decisions

At 32, my only sister developed early stage breast cancer with no lymph node involvement. With no family history of breast cancer, we thought her diagnosis was an anomaly. Her medical team considered a double mastectomy to be too radical for someone so young, so she had lumpectomy, radiation, and chemotherapy. Nine months later, a new primary cancer appeared in her other breast. This time it was in her lymph nodes. Within months, it spread to her lungs, bones, and brain. Her oncologist said genetic testing wouldn’t change her treatment. He didn’t consider whether it would affect me or other female relatives, and he never recommended a genetic counselor. My sister passed away, leaving her 4-year-old child without a mother.

Terrified about my own health, I rejoiced when my BRCA test result was negative. My celebration was short-lived when I learned that a negative test means little when there is no known familial mutation. My anxiety soared out of control. I bruised myself looking for breast lumps, and I needed antidepressants to get through the days. Then I decided not to duplicate my sister’s experience. I learned about prophylactic mastectomy and oophorectomy and contacted doctors. Finally, through FORCE, I was advised to see a genetic counselor. I insisted we had no history of breast or ovarian cancer: my mother, her two sisters, and their mother were alive and well. My father’s only sister and her daughters were too. The only cancer casualties were my paternal great-grandmother (unknown young-onset cancer) and grandmother (“stomach cancer”). My counselor explained that the “stomach cancer” could have been ovarian cancer and showed how a mutation could have passed from my father to my sister without affecting other female relatives. She urged me to have my parents tested. I left feeling scared, yet also empowered that my uninformative test could be informative if either parent tested positive.

—RHONDA

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree