Introduction

The prostate is a small gland, surrounding the urethra, located between the penis and the bladder. The prostate is perhaps the most disease-affected organ in the male body. The three main conditions that can affect the prostate are:

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), that is, an enlarged prostate that causes urinary problems. It is a common condition that is associated with ageing. About 60% of men who are 60 years of age or over have some degree of prostate enlargement. BPH can be treated with medication, a minimally invasive procedure or, in extreme cases, surgery that removes the prostate.

- Cancer of the prostate is one of most common cancers in men over 65 years old. The risk of developing prostate cancer increases with age. The progression of this cancer is very slow and it can take up to 15 years to develop metastasis (most often in bones), so the specific mortality is weak. The screening of prostate cancer is based on digital rectal examination and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) assay. Prostate cancer can be cured when treated in its early stages. Treatments include removing the prostate, hormone therapy and radiotherapy. All the treatment options carry the risk of significant side effects, including loss libido, sexual dysfunction and urinary incontinence.

- Prostatitis is inflammation of the prostate gland. There are different forms of prostatitis based on causes and chronology (acute or chronic). The inflammation can be due to bacterial infection with an acute or chronic presentation. These forms are treated with antibiotics. Most often (in ∼95% of cases) the diagnosis is a chronic non-bacterial prostatitis or male chronic pelvic pain syndrome that is treated with a large variety of modalities.

This chapter reviews these main diagnostic entities and the approach to treatment in the ageing male.

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

BPH is very common and its incidence is correlated with the ageing population. Autopsy data show that nearly 90% of all men aged 80 years and above have anatomical or microscopic evidence of hyperplasia and that pathology is found in half of men in their 50s.1

BPH is commonly associated with bothersome lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) such as urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia, decreased and intermittent strength of stream and the sensation of incomplete bladder emptying, which can seriously impair quality of life.

The term ‘BPH’ actually refers to a histological condition, namely the presence of stromal-glandular hyperplasia within the prostate gland.2 The condition becomes clinically relevant if and when it is associated with bothersome LUTS. However, the relationship between BPH and LUTS is complex, because some men with histological BPH will develop significant LUTS, whereas other men who do not have histological BPH will develop LUTS.3 Epidemiology, clinical expressions, diagnostic approach and treatment of BPH are discussed is this chapter.

Epidemiology

Mortality

BPH is a common problem among elderly men and leads to substantial disability. However, it is not a frequent cause of death. Mortality from BPH declined dramatically in industrialized countries from the 1950s to the 1990s.4 Moreover, a cohort study of 4708 men who underwent transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) between 1976 and 1984 at the Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in Oakland, OR, revealed no greater mortality than age-matched men who did not undergo TURP.5

The decrease in mortality can result either from a reduction in disease prevalence or from improvements in survival. To date, there is no evidence that the decrease in BPH mortality is likely to be related to improvements in medical and surgical treatments provided. Indeed, it could be considered as a health care performance indicator.6

Prevalence

BPH is increasingly common with advancing age. About 8% of men aged 31–40 years show histological evidence of BPH. This rate increases sharply to 50, 70 and 90 in men aged 51–60, 61–70 and 81–90 years, respectively.7 Clinical BPH, defined by moderate-to-severe LUTS, occurs in ∼25% of men aged 50–59 years, in 33% of men aged 60–69 years and in 50% of men older than 80 years.7 Aetiologies of LUTS are multifactorial but BPH is a major contributing factor. Age-elated, detrusor dysfunction, neurogenic disease and diabetes are other major causes of LUTS.8 The prevalence of LUTS in Europe varies with age, ranging from 14% in the fourth decade to >40% in the sixth decade. Based on an overall prevalence of LUTS of 30%, approximately four million men older than 40 years suffer from LUTS in the UK.9 Furthermore, with the ageing population, the prevalence of BPH and its impact on medical practice will increase dramatically in the future.3

Pathogenesis and Risk Factors of BPH

BPH initially grows in the periurethral or transitional zone, with a fourfold increase in stromal tissue and a twofold increase in glandular components. However, the pathogenesis of BPH remains vague. Multiple factors contribute to the development of BPH10 but the two main ones are changes in hormone level with age. Thus, the development of BPH requires both functional Leydig cells and ageing. However, given that testosterone, dihydrotestosterone and estrogen may be involved in BPH development, these hormones are not sufficient to cause BPH. Other factors influence the risk of developing BPH:

- Age: Several studies have demonstrated a relationship between age and markers of BPH progression.11, 12

- Genetic susceptibility: Positive family history of BPH increases the risk of having more moderate to severe LUTS.13 Moreover, twin studies suggest that heredity is a more important determinant of lower urinary tract symptoms than age, transition zone volume or total prostate volume.14

- Race: Black men are more likely than white men to have more moderate to severe LUTS.13 In contrast, Asian men are less likely than white and black men to have BPH.15

- Free PSA levels: Higher free PSA levels increase the risk of BPH.16

- Heart disease: Heart disease increases the risk of BPH.16

- Physical activity: Lack of physical exercise increase the risk of BPH.16

- Inflammation: Epidemiological data show a strong relationship between prostatitis and BPH.17

- Medications: Use of β-blockers increases the risk of BPH.16

- Other factors: Conditions such as hyperinsulinaemia, dyslipidaemia, elevated blood pressure and obesity have been identified as risk factors of BPH.18, 19

Natural History

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) include increased frequency of urination, nocturia, hesitancy, urgency and weak urinary stream. These symptoms typically appear slowly and progress gradually over years. Untreated BPH can cause acute urinary retention (AUR), recurrent urinary tract infections, hydronephrosis and renal failure.

One of the largest longitudinal studies, the Olmsted County study conducted in the USA, enrolled 2215 men aged 40–79 years. At 92 months’ follow-up, 31% of participants reported a ≥3-point increase in AUA Symptom Index (AUA-SI; identical with the seven symptom questions of the IPSS) score and the mean annual increase in AUA-SI was 0.34 points.20, 21 Moreover, in the placebo arm of the Medical Therapy Of Prostatic Symptom (MTOPS) study, the overall clinical progression rate (defined as an increase in AUA-SI of ≥4 points, AUR, urinary incontinence, renal insufficiency or recurrent urinary tract infections) was 17.4% over the 4 year follow-up. About 78% of progression events were worsening symptoms.22

Although AUR and surgery are less common than overall symptomatic worsening, they represent important progression events with financial, emotional and health-related consequences for patients. Untreated men with symptomatic BPH have about a 2.5% per year risk of developing AUR.23, 24 Age, LUTS, urinary flow rate and prostate volume are risk factors for AUR in population-based studies, but not in all clinical trials. Moreover, serum PSA seems to be a stronger predictor of prostate growth than age or baseline prostate volume25 and should be a good risk predictor of AUR.22

Diagnostics

Patient Evaluation

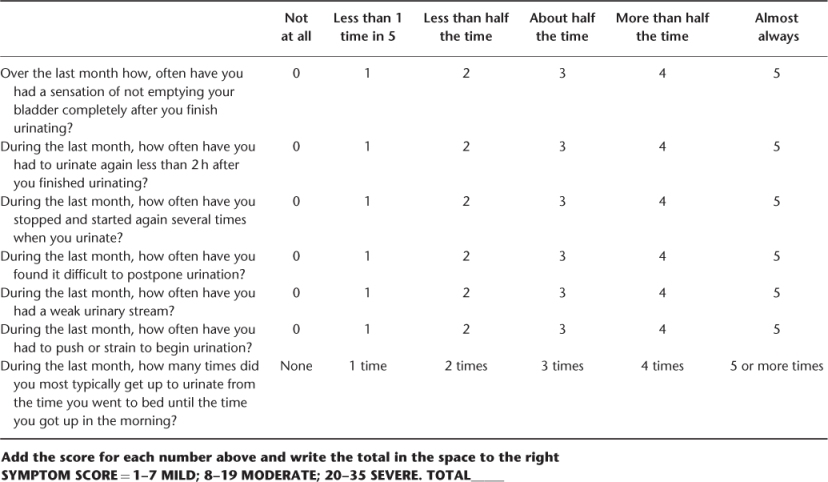

Urinary symptoms may be evaluated using the American Urologic Association (AUA) symptoms score or the International Prostate Symptoms Score (IPSS) (Table 105.1).

Table 105.1 AUA Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Symptom Score (AUA Practice Guidelines Committee, 2003).

The AUA symptom score should only be used to assess the BPH severity symptoms (not for differential diagnosis). It includes seven questions: frequency, nocturia, urinary stream weakness, straining, intermittency, incomplete emptying and urgency. Each of these items is scored on a scale from 0 (not present) to 5 (almost always present). Symptoms are classified from mild (total score 0–7) to moderate (total score 8–19) or severe (total score 20–35). The AUA symptom score is a useful tool for assessing symptoms over time in a quantitative way. The International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) uses the same items and adds a disease-specific quality of life question: ‘If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary condition the way it is now, how would you feel about that?’.

However, before one concludes that a man’s symptoms are related to BPH, other disorders which can cause similar symptoms should be excluded by history, physical examination and several simple tests.

The history may provide important diagnostic information:

- History of type 2 diabetes: nocturia.

- Symptoms of neurological disease: neurogenic bladder.

- Sexual dysfunction related LUTS.

- Gross haematuria or pain in the bladder area: bladder tumour or calculi.

- History of urethral trauma, urethritis or urethral instrumentation: urethral stricture.

- Family history of BPH and prostate cancer.

- Treatment with drugs that can impair bladder function (anticholinergic drugs) or increase outflow resistance (sympathomimetic drugs).

Physical examination should include digital rectal examination (DRE) to assess prostate size and consistency and to detect nodules or induration suggesting a prostate cancer. Rectal sphincter tone should be determined and a neurological examination performed.

A general health and cognitive status evaluation is useful for choosing the best treatment, especially if a surgical procedure is required. Clearly, dementia among many neurological conditions could affect urinary condition.

Laboratory Evaluation

Urinalysis should be done to detect urinary infection and haematuria. Urine cytology may be helpful for bladder tumour diagnosis in men with predominantly irritative symptoms (frequency, urgency, nocturia) or haematuria especially with a smoking history.

A high serum creatinine may be due to bladder outlet obstruction or to underlying renal or prerenal disease; it also increases the risk of complications and mortality after prostatic surgery. Serum creatinine used to be recommended, but studies have shown that it is not mandatory without comorbidity.26 In contrast, the European Association of Urology considers it to be a cost-effective test. Bladder, ureters and kidneys ultrasounds are indicated if the serum creatinine concentration is subnormal.

PSA measurement remains controversial. Serum PSA specificity in men with obstructive symptoms is lower compared with asymptomatic patients. PSA is not cancer specific and could be increased in different prostatic disorders, including BPH. Moreover, 25% of patients with a prostate cancer have a normal PSA (4.0 ng ml−1 or less, a widely used cut-off value).

Regarding BPH guidelines,26 recommendations refer to patients with a life expectancy of >10 years.

Treatment2

LUTS of BPH progress slowly, with some patients progressing more rapidly than others. The physician can predict the risk of progression from the patient’s clinical profile. Also, increased symptom severity, a poor maximum urinary flow rate and a high post-void residual urine volume are major risk factors for overall clinical progression of LUTS/BPH.27 Also, therapeutic decision-making should be guided by the severity of the symptoms, the degree of bother, the patient’s risk profile for progression and patient preference. Information on the risks and benefits of BPH treatment options should be explained to all patients.

The treatment for LUTS can be separated into four groups: watchful waiting, medical therapy, minimally invasive treatment and invasive surgical therapy.

Watchful Waiting

Patients with mild symptoms (IPSS <7) should be counselled about a combination of lifestyle and watchful waiting. They should have periodic physician-monitored visits. Patients with mild symptoms and severe bother should undergo further assessment.

A variety of life style changes may be suggested:

- fluid restriction, particularly prior to bedtime

- avoidance of caffeinated beverages and spicy foods

- avoidance/monitoring of some drugs (e.g. diuretics)

- timed or organized voiding (bladder retraining)

- pelvic floor exercises

- avoidance or treatment of constipation.

Medical Treatment

α-Blockers

α-Blockers are an excellent first-line therapeutic option for men with symptomatic bother who desire treatment. Alfuzosin, doxazosin, tamsulosin, terazosin and silodosin are appropriated treatment options for LUTS secondary to BPH. They do not alter the natural progression of the disease. Adverse side effects commonly reported with different alpha-blockers include dizziness, headache, asthenia, postural hypotension, rhinitis and sexual dysfunction, most commonly occurring in ∼5–9% of patient populations.

5α-Reductase Inhibitors

The 5α-reductase inhibitors (duasteride and finasteride) are appropriate and effective treatments for patients with LUTS associated with demonstrable prostatic enlargement. Because of the mechanism of action, it takes 3–6 months for full clinical effect.

Combination Therapy

The combination of an α-adrenergic receptor blocker and a 5α-reductase inhibitor is an appropriate and effective treatment strategy for patients with LUTS associated with prostatic enlargement. The MOST trial demonstrated maximum effect in reducing prostate size and improving symptoms by combining an α-blocker (doxazosin) with an α-reductase inhibitor (finasteride).22 Combination medical therapy can effectively delay symptomatic disease progression, while combination therapy and/or 5α-reductase monotherapy is associated with decreased risk of urinary retention and/or prostate surgery. Patients successfully treated with combination therapy may be given the option of discontinuing the α-blocker after 6–9 months of therapy. If symptoms recur, the α-blocker should be restarted.

Role of Anticholinergic Medications

Evidence suggests that for selected patients with bladder outlet obstruction due to BPH and concomitant detrusor overactivity, combination therapy with an α-receptor antagonist and anticholinergic can be helpful.28

Caution is recommended, however, when considering these agents in men with an elevated residual urine volume or a history of spontaneous urinary retention. These kinds of medications also increase the risk of delirium in patients with cognitive impairment.

Phytotherapies

Phytotherapies for BPH are becoming increasingly popular and, although many physicians remain sceptical of their value, patients generally seem satisfied with their utility. Two of the more common herbal medications used include Serenoa repens (saw palmetto) and Pygeum africanum (Prunus africana). They have shown some efficacy in several small clinical series but cannot be recommended as the standard treatment of BPH.

Minimally Invasive Treatment

Transurethral Microwave Therapy (TUMT)

TUMT is a reasonable treatment consideration for the patient who has moderate symptoms, small to moderate gland size and a desire to avoid more invasive therapy for potentially less effective results.29 TUMT may be associated with a higher retreatment rate over a 5 year follow-up interval than for men receiving TURP.29

Transurethral Needle Ablation (TUNA)

TUNA is an other minimally invasive therapy recommended as treatment options. The TUNA device is a rigid cystoscope-like instrument passed transurethrally under vision. Utilizing a radiofrequency signal, the tissue is heated to between 46 and 100 °C. TUNA may be a therapeutic option for the relief of symptoms in the younger, active individual in whom sexual function remains an important quality of life issue (less risk of retrograde ejaculation); however, limited data are available on long-term outcomes.30

Surgery

Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP)

A TURP can be performed with a regional block under or general anaesthesia. The procedure takes 60–90 min and generally requires a 24 h observation period in the hospital. A resectoscope loaded with a diathermy loop is introduced into the bladder. Under direct vision, strips of prostatic adenoma are resected one at a time and dropped into the bladder. This is continued until the entire adenoma is resected. At the end of the operation, the prostate chips are evacuated from the bladder and haemostasis achieved with electrocautery. The prostatic fossa is left with a wide open, bound by its capsule. The cavity will be lined by a regenerated epithelial surface in 6–12 weeks. Until the fossa is completely epithelialized, the patient is vulnerable to bleeding; the patient should avoid straining for at least 6 weeks.

TURP remains the gold standard treatment for patients with bothersome moderate or severe LUTS who request active treatment or who either fail or do not want medical therapy. Furthermore, patients should be informed that the procedure may be associated with short- and long term complications.31 For frail patients, transurethral plasma vaporization of the prostate in saline (TUVis) could be useful. As opposed to the conventional transurethral resection of the prostate, this new procedure does not cut and shave off tissue with a loop but energetically vaporizes the tissue with a small electrode. Bleeds during and after this surgery can be avoided. This surgical technique should be proposed to frail patients especially with blood thinner treatments.

Transurethral Incision of the Prostate (TUIP)

TUIP is appropriate surgical therapy for men with prostate gland sizes <30 g. These patients should experience symptom improvements similar to TURP with a lower incidence of retrograde ejaculation.32

Laser Prostatectomy

Several methods for laser prostatectomy have been developed, including ultrasound- and endoscopic-guided approaches.33 A systematic review evaluated 20 randomized trials involving 1898 patients, including 18 comparing TURP with contact lasers, non-contact lasers and hybrid techniques:34

- The pooled percentage improvements for mean urinary symptoms ranged from 59 to 68% with laser treatments and from 63 to 77% with TURP.

- Improvements in mean peak urinary flow ranged from 56 to 119% with laser treatments and from 96 to 127% with TURP.

- Laser-treated subjects were less likely to require transfusions (<1 versus 7%) or develop strictures (4 versus 8%) and their hospitalizations were 1–2 days shorter.

- Surgical reintervention occurred more often after laser procedures than TURP (5 versus 1%).

Data were too limited to draw conclusions about the preferred laser technique or to compare laser treatment with other minimally invasive procedures, but patients treated with non-contact laser prostatectomy were more likely to have dysuria than patients treated with TURP or contact laser prostatectomy. In many centres, laser treatment of BPH has evolved from coagulation to enucleation with the holmium laser (HoLEP: holmium laser enucleation of the prostate). This instrument is not dependent upon prostate size and tissue can be preserved for histology. A meta-analysis of four small randomized trials comparing TURP with HoLEP found significant heterogeneity across studies, but concluded that peak flow rates were similar after either therapy and that TURP required less operating room time but resulted in more blood loss, longer catheterization times and longer hospital stays.35

Open Prostatectomy

Open prostatectomy accounts for <5% of operations for BPH in the USA,36 but it is performed more often in other countries. Open prostatectomy remains indicated for men whose prostates, in the view of the treating urologist, are too large for TURP for fear of incomplete resection, significant bleeding or the risk of dilutional hyponatraemia.

Prostate Cancer

Epidemiology

Prostate cancer is an extremely frequent malignant disease. It represents the second most common cancer in men after lung cancer and the fifth cause of death by cancer in the world. According to GLOBOCAN statistics, 6 79 023 new cases of prostate cancer were diagnosed worldwide in 2002 and 2 21 002 men died of this disease during the same year, representing 5.8% of cancer mortality in humans.37

The epidemiological impact of prostate cancer varies from one country to another because of health policies or screening, but Western countries such as the USA, Australia and New Zealand and Western Europe are particularly concerned. Given the ageing population and its increasing incidence with age, prostate cancer affects mainly elderly men. In the USA, according to SEER data (Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results) from 2000 to 2005, the median age at diagnosis of prostate cancer was 68 years, with 25.7% of cases diagnosed in men ≥75 years of age. Over 90% of deaths occurred in men ≥65 years of age and 71.2% in men ≥75 years of age.38

Principal individual risks factors of developing a prostate cancer are increasing age and heredity and ethnicity. In the USA, compared with white men, black men have a 40% higher risk of the disease and twice the rate of death.39 Exogenous factors (food consumption, pattern of sexual behaviour, alcohol consumption and occupational exposure) may have an important impact on this risk. Several ongoing large randomized trials are trying to clarify the role of such risk factors and the potential for successful prostate cancer prevention.40

Diagnosis and Screening

In the PSA era, procedures for prostate cancer diagnosis have changed considerably. Diagnosis is based clinically, on digital rectal examination (DRE), and biologically, on PSA assay. Diagnosis is confirmed by pathological evaluation of prostate biopsies. Regarding pathology, adenocarcinoma represents 98% of cases and most often arises from the peripheral part of the prostate. Among pathological features, differentiation of tumour tissue given by the Gleason score is particularly important.39, 40

Based on the preliminary results of large ongoing screening trials, widespread mass screening is not appropriate at present. However, major urological societies recommend early diagnosis in well-informed men.40 Thus, the French Urological Association (AFU) recommends performing a DRE and PSA test per year from age 55 years (or 45 years if there are risk factors) to 69 years according to the results the results of the European screening study ERSPC. Before 55 and after 69 years, tests should be proposed based on individual criteria.41

For elderly patients, in case of symptoms, it is necessary to obtain pathological evidence of prostate cancer to propose specific management. Therapeutic options (hormonal therapy, radiotherapy, analgesics) are usually feasible in this situation.

For asymptomatic patients, it is necessary take into account the individual probability of survival to propose early diagnosis tests. It is important, however, to maintain regular DRE assessment in older men to detect the onset of locally advanced prostate cancer potentially responsible for disabling symptoms. In this situation, even frail elderly patients may benefit from the specific treatment.

Management of Localized Prostate Cancer

The management of localized prostate cancer40 is based on classifications depending on relapse risk. The most widely used classification is that of D’Amico et al.42 Patients are divided into three groups depending on the probability of biological relapse after local treatment of prostate cancer by surgery, radiotherapy or brachytherapy. This classification is based on DRE, PSA and Gleason score (Table 105.2).

Table 105.2 Groups of D’Amico et al.42.

| Low risk | Intermediate risk | High risk |

| Stage <T2b | Stage T2b | Stage ≥T2c |

| AND PSA ≤ 10 ng ml−1 | OR 11 ≤ PSA ≤ 20 ng ml−1 | OR PSA >20 ng ml−1 |

| AND biopsy Gleason score <7 | OR biopsy Gleason score = 7 | OR biopsy Gleason score ≥8 |

Low-Risk Patients

- Watchful waiting:

- DRE T1 or T2a (Table 105.3)

- PSA <10 ng ml−1

- Gleason score ≤6, no grade 4

- ≤2 positive biopsies

- ≤50% of cancer in each biopsy.

- Radical prostatectomy (bilateral ilio-obturator lymphadenectomy is optional).

- Brachytherapy:

- ≤cT2b

- PSA <10 ng ml−1

- Gleason score ≤6

- prostatic volume ≤50 cm3

- IPSS <12.

- Conformational external beam radiation therapy (prostate volume alone, dose of 70 Gy or more).

Table 105.3 TNM classification.

| T1−T2 | Localized prostate cancer not extending beyond the capsule (no lymph node, absence of metastasis, that is, N0M0) |

| T1 | Only histological finding (not visible to imaging and non-palpable) |

| T1a | <5% of cancer cells on the samples |

| T1b | >5% |

| T2 | Cancer palpable on rectal examination |

| T2a | Cancers with <50% of both prostate lobes |

| T2b | >50% |

| T2c | Involvement of both lobes |

| T3: Extension of cancer in the peripheral tissues (crossing of the | |

| prostate capsule) | |

| T3a | Extension beyond capsule |

| T3b | Involvement of seminal vesicles |

| T4: extension to adjacent organs: bladder, rectum, pelvic wall | |

| N0 or N1 | Absence or presence of lymph node(s) |

| M0 or M1 | Presence or absence of metastasis(es) |

Intermediate-Risk Patients

- Radical prostatectomy with lymphadenectomy.

- Conformational external beam radiation therapy dose ≥74 Gy.

- Conformational external beam radiation therapy with a short course of hormonal therapy with LH–RH agonists (6 months).

High-Risk Patients

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree