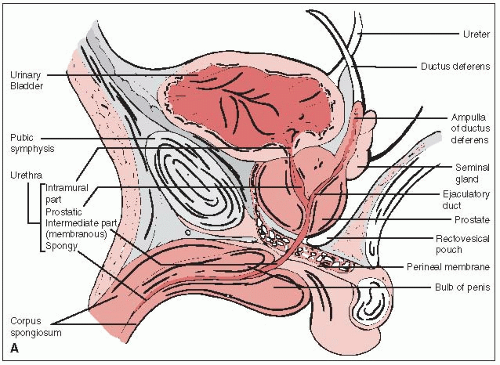

The prostate gland surrounds the male urethra between the base of the bladder and the urogenital diaphragm (Fig. 32-1A).

The prostate is attached anteriorly to the pubic symphysis by the puboprostatic ligament and is separated from the rectum posteriorly by Denonvilliers’ fascia (retrovesical septum), which attaches above to the peritoneum and below to the urogenital diaphragm.

The seminal vesicles and the vas deferens pierce the posterosuperior aspect of the gland and enter the urethra at the verumontanum (Fig. 32-1B).

The prostate is divided into the anterior, median, posterior, and two lateral lobes. The posterior lobe, extending across the entire posterior surface of the gland, is felt on rectal examination.

Others divide the glandular prostate into an inner portion (periurethral glands and transition zone) and an outer portion (central and peripheral zones). The nonglandular prostate encompasses the prostatic urethra and the anterior fibromuscular stroma (16).

Myers et al. (49), in a study of 64 gross prostatectomy specimens, emphasized variations in the shape and the exact location of the prostatic apex, which should be considered in planning radiation therapy.

Currently, most carcinomas of the prostate are found because of elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level. The tumor is not palpable in most patients.

Depending on the histologic grade (Gleason score) and pretreatment PSA, extracapsular extension is currently detected in less than 10% of patients on rectal digital examination. Palpable tumors are noted in approximately 30% to 40% of patients (78).

The tumor may spread to the pelvic lymph nodes, and the incidence of metastatic disease is closely related to the pretreatment PSA level and Gleason score. Currently, less than 5% of patients with stage T1c are found to have positive lymph nodes (52). The tumor may eventually involve the periaortic lymph nodes.

Distant metastases are almost never seen as the initial manifestation of prostatic cancer at the present time. However, several years after posttreatment elevation of the PSA, patients who fail primary treatment will develop distant metastases, primarily to the bones and less frequently to the liver or lungs.

Patients with localized prostatic carcinoma are frequently asymptomatic; the diagnosis is often made because of an abnormal screening or routine PSA test or, less frequently, during a routine rectal examination.

Stage T1 tumors may occasionally be diagnosed at transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).

Patients with larger tumors may have urethral obstruction with frequency, nocturia, hesitancy, and narrow stream. Isolated hematuria or hematospermia is extremely rare.

Rarely, patients with advanced disease present with pain or stiffness caused by bony metastases (15, 57).

TABLE 32-1 Diagnostic Workup for Carcinoma of the Prostate

Routine

Clinical history and clinical examination

Rectal examination

Laboratory studies

Complete blood cell count, blood chemistry

Serum PSA measurement

Plasma acid phosphatase (prostatic/total) measurement

Radiographic imaging

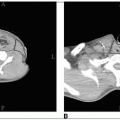

CT or MRI scan of pelvis and abdomen

Intravenous pyelography

Chest x-ray

Radioisotope bone scan

Transrectal ultrasonography

Cystourethroscopy

Needle biopsy of prostate (transrectal, transperineal)

Transurethral resection, if indicated

Source: From Perez CA. Prostate. In: Perez CA, Brady LW, eds. Principles and practice of radiation oncology, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven, 1998:1583-1694, with permission.

ProstaScint scan (Cytogen, Princeton, NJ) was found to have some value in staging of primary prostate cancer. The test is primarily used in patients with rising PSA after radical prostatectomy to detect tumor activity in the pelvic or periaortic lymph nodes (82).

Findings on digital examination of the prostate, as well as other studies, determine the stage of the disease, which is classified according to the Jewett-Whitmore or the American Joint Committee system (Table 32-2).

Primary tumor stage, pretreatment PSA level, and pathologic tumor differentiation (Gleason score) are the strongest prognostic indicators.

Several nomograms, tables, and formulae that use the above parameters have been proposed to divide patients into prognostic groups and predict the probability of extracapsular tumor extension, seminal vesicle involvement, or lymph node metastases (53 and 54, 66, 69).

Patients with Gleason score of 7 have a relatively poor prognosis, which is worse in those with 4 + 3 score in comparison with 3 + 4 score (14, 76).

Elevated PSA values after radical prostatectomy or 6 months after definitive irradiation are sensitive indicators of persistent disease.

TABLE 32-2 American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System for Prostate Cancer

Primary tumor (T) (clinical categories)

TX

Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0

No evidence of primary tumor

T1

Clinically inapparent tumor neither palpable nor visible by imaging

T1a

Tumor incidental histologic finding in 5% or less of tissue resected

T1b

Tumor incidental histologic finding in more than 5% of tissue resected

T1c

Tumor identified by needle biopsy (e.g., because of elevated prostate-specific antigen, PSA)

T2

Tumor confined within prostatea

T2a

Tumor involves one half of one lobe or less

T2b

Tumor involves more than one half of one lobe but not both lobes

T2c

Tumor involves both lobes

T3

Tumor extends through the prostate capsuleb

T3a

Extracapsular extension (unilateral or bilateral)

T3b

Tumor invades seminal vesicle(s)

T4

Tumor is fixed or invades adjacent structures other than seminal vesicles: such as external

sphincter, rectum, bladder, levator muscles, and/or pelvic wall

Regional lymph nodes (N)

NX

Regional lymph nodes were not assessed

N0

No regional lymph node metastasis

N1

Metastasis in regional lymph node(s)

Distant metastasisc

M0

No distant metastasis

M1

Distant metastasis

M1a

Nonregional lymph node(s)

M1b

Bone(s)

M1c

Other site(s) with or without bone disease

a Tumor found in one or both lobes by needle biopsy, but not palpable or reliably visible by imaging, is classified as Tlc.b Invasion into the prostatic apex or into (but not beyond) the prostatic capsule is classified not as T3 but as T2.c When more than one site of metastasis is present, the most advanced category is used. pM1c is most advanced. Source: Staging from Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., eds. AJCC cancer staging manual, 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer Verlag, 2009, with permission.

Combined with histologic grade, PSA, and pathologic stage, DNA ploidy provides a highly sensitive prognostic indicator. Aneuploidy is associated with more aggressive tumors in comparison with diploid lesions.

S-phase fraction is a better predictor of survival in men with prostate cancer than DNA ploidy, although it is not an independent prognosticator in locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer.

p53 mutations in localized carcinoma of the prostate are uncommon (27); p53 overexpression may be associated with decreased response to irradiation (radioresistance marker).

Some authors have observed lower survival rates for a given stage of disease in black men compared with white patients, whereas others have not (2, 57). This difference may be related to a larger tumor volume (higher pretreatment PSA), lower immune competence, more biologically aggressive tumors, testosterone level, environmental or socioeconomic conditions, and genetic or other unknown factors.

Recently, it has been suggested that obesity predicts for higher grade and higher stage tumors (23).

Asbell et al. (5) documented the impact of surgical staging on outcome of irradiation in patients with clinical stage A2 and B disease. The 5-year disease-free survival rate was 76% in patients with negative pelvic lymph nodes at lymphadenectomy and 63% in those staged by radiographic imaging (p = 0.008).

Hanks et al. (28) corroborated this observation; they concluded that radiographic determination of lymph node status had no prognostic value and should not be used for stratification of patients in clinical trials.

TURP has been correlated with a higher incidence of distant metastases and decreased survival (36). In patients with B2 and C tumors, better disease-free survival was noted in patients diagnosed with needle biopsy (p = 0.021).

Patients with T3 or T4, moderately or poorly differentiated tumors (Gleason score of 8 to 10) diagnosed by TURP have a higher incidence of distant metastases and decreased survival than patients having needle biopsy (57).

Adenocarcinoma, arising from peripheral acinar glands, is the most common tumor in the prostate. It is graded as well, moderately, or poorly differentiated.

Gleason et al. (25, 26) initially proposed a prognostic classification system based on clinical stage and the primary and secondary morphologic patterns of the tumor, each graded from 1 to 5. Later, only pathologic features were scored (up to 10).

Periurethral duct carcinoma is usually of the transitional cell type, sometimes mixed with glands. This tumor does not invade the perineural spaces as commonly as adenocarcinoma of the prostate.

Ductal adenocarcinoma rarely arises from the major ducts. Originally, this lesion was thought to originate in the prostatic utricle, a müllerian remnant; however, most ductal adenocarcinomas behave as acinar adenocarcinomas. Some authors believe that these tumors are relatively benign, yet most reports point to aggressive behavior. The tumor is not hormonally responsive but is moderately sensitive to radiation therapy. The treatment of choice is radical cystoprostatectomy.

Transitional cell carcinoma of the prostate is rare. Lymph node metastases were found in 14 of 26 patients (54%) with stromal invasion compared with 4 of 17 (24%) with duct/acinar involvement (68).

Neuroendocrine tumors are a rare variant of a malignant tumor composed of small or carcinoid-like cells. Neuroendocrine cell substances found in these tumors include serotonin, neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin, and calcitonin. Prostatic acid phosphatase and PSA are valuable in determining the prostatic origin of the tumor.

Mucinous carcinoma, not arising in major ducts or in the urethra, with positive histochemical stains for prostatic acid phosphatase has been reported.

Sarcomatoid carcinoma, a rare tumor that is difficult to distinguish from a true sarcoma, is considered a very aggressive variant of prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is rare in the prostate (less than 0.1% of all tumors of this gland).

Other epithelial tumors, such as carcinoid, have been reported in the prostate.

Squamous cell carcinoma originating primarily in the prostate is extremely rare.

Metastatic malignant tumors from other locations to the prostate are occasionally reported (57)

Sarcomas (leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, or fibrosarcoma) constitute approximately 0.1% of all primary neoplasms of the prostate. Leiomyosarcoma is more common in middleaged or older men, whereas rhabdomyosarcoma is found more frequently in younger patients. Several cases of malignant schwannoma have been described.

Primary lymphoma of the prostate is extremely rare; fewer than 100 cases have been reported (77). Lesions may vary from diffuse small noncleaved to diffuse large cell lymphomas. The prostate is considered an extranodal site, and according to the Ann Arbor staging system, these lesions are staged as IE. However, if there is involvement of the lymph nodes and bone marrow, they are classified as IVE. Prognosis is generally poor.

An excellent review of the pathology of prostatic carcinoma was published by Mostofi et al. (48).

Nearly every stage of localized prostate cancer has multiple treatment options available, ranging from active surveillance to a combination of treatment modalities.

Life expectancy, conservative management, and quality of life related to each of the management options should be carefully discussed with the patient and spouse or significant other (101).

Albertsen reports on 20-year follow-up of men who were either observed or who only received androgen deprivation therapy for their prostate cancer. Overall, in the first 15 years, there was a 3.3% risk of death per year from prostate cancer, while after 15 years, this risk dropped to 1.8%. Over 20 years, those with Gleason 2 to 4 disease had a 0.6% risk of dying from prostate cancer per year. Over the first 10 years of follow-up, in those with Gleason 8 to 10 tumors, the risk of dying of prostate cancer was approximately 12% per year (3).

A Swedish report on a 15-year follow-up of patients who were managed with watchful waiting showed that 37% of deaths were related to prostate cancer. Of those with T0-2 disease, the 81% rate of 15-year survival was similar in those who deferred or received initial treatment. In those who had T3-4 disease, the 15-year survival was 57%, while in those with metastatic disease, it was 6% (34).

An analysis of SEER data over a 12-year period compared survival in patients who had received treatment with radiation therapy or surgery versus those who did not have surgery, irradiation or androgen deprivation therapy. After 12 years, a statistically significant survival advantage was associated with treatment. In the observation group, there was a 37% death rate versus 23% in the treatment group (96).

A Scandinavian study randomized patients with clinically localized prostate cancer to radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting. The most recent update, with a median 10.8 years of follow-up, showed that the 12-year prostate cancer death rate was statistically significantly improved in the surgery group (12.5% versus 17.5%). There was also a significant benefit in the rate of developing distant metastases (7).

Many types of hormonal therapy have been used to reduce androgenic stimulation of prostate carcinoma by ablation of androgen-producing tissue, suppression of pituitary gonadotropin release, inhibition of androgen synthesis, or interference with androgen action in target tissues.

Orchiectomy removes 95% of circulating testosterone and is followed by a prompt, longlasting decline in serum testosterone levels.

Diethylstilbestrol (3 mg per day) reduces serum testosterone to castrate levels; higher doses have no additional effect (80). Diethylstilbestrol is no longer commercially available in the United States.

Progestational agents, such as megestrol (Megace), suppress gonadotropin release and may directly interfere with hormone synthesis (24).

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone [LHRH] agonists), such as goserelin, leuprolide, and buserelin, cause an initial rise in gonadotropin levels, followed by a sharp decline within 2 to 3 weeks. Parallel changes occur in levels of circulating testosterone, interfering with androgen production in the adrenal gland.

Aminoglutethimide, which is administered with a glucocorticoid, inhibits the synthesis of all adrenal steroids and can further reduce serum testosterone levels in castrate patients (97).

Flutamide, a nonsteroidal antiandrogen, does not suppress gonadotropin or testicular testosterone levels but blocks the effect of 5a-reductase, inhibiting formation of dihydrotestosterone and inhibiting androgen uptake and nuclear binding in the prostate cell; it has estrogenic side effects yet, in contrast to other antiandrogens, infrequently produces sexual impotence (104). Recommended dose is 250 mg 3 times daily. Diarrhea is a frequent side effect.

Bicalutamide (Casodex) (50 mg daily) is a steroid antiandrogen that binds to cytosol androgen receptors, producing decreased testosterone levels and elevation of gonadotropins (51). Monotherapy with 150 mg daily of bicalutamide was found to have therapeutic effects equivalent to surgical castration (33).

Recently, LHRH antagonists have become available for use, and their appropriate incorporation into treatment regimens is being explored.

Endocrine therapy before or in conjunction with irradiation and as adjuvant therapy after irradiation for patients at high risk of occult metastatic disease and as neoadjuvant cytoreductive therapy in patients with bulky primary tumors to enhance likelihood of local tumor control has been shown to decrease local tumor recurrence and distant metastases.

The RTOG randomized patients with bulky tumors to external beam radiation therapy alone versus external beam radiation therapy with neoadjuvant and concurrent androgen deprivation therapy. The most recent update shows a statistically significant improvement with androgen deprivation in disease-free survival (11% versus 3%), incidence of distant metastases (35% versus 47%), and biochemical failure (65% versus 80%) at 10 years (70).

Another RTOG trial randomized patients with palpable tumor extending outside the prostate (T3) to external beam radiotherapy versus external beam radiotherapy and adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy administered until failure. The most recent update shows a statistically significant improvement with androgen deprivation for absolute survival (49% versus 39%) at 10 years (64).

The EORTC showed an overall survival benefit with concurrent and adjuvant (3 years) androgen deprivation therapy (10).

The RTOG also randomized patients with cT2c-T4 who received external beam radiation therapy to short-term (neoadjuvant and concurrent) or long-term androgen deprivation

therapy (neoadjuvant, concurrent, and adjuvant for 2 years). Statistically significant benefit was seen for all endpoints other than overall survival for the overall study population at 10 years. In the subgroup of patients with Gleason 8 to 10 tumors, an overall survival benefit (31.9% versus 45.1%) was seen as well (31).

A recently reported EORTC study showed a general 5-year overall survival benefit for 3 years of androgen deprivation therapy versus 6 months (11).

One randomized trial including men with localized prostate cancer with unfavorable risk factors showed an overall survival benefit with 6 months of androgen deprivation therapy. Analysis of the results suggested that in men with significant comorbidity, there may not be a benefit to the administration of androgen deprivation (18).

Patients with high-risk prostate cancer generally receive long-term androgen deprivation therapy and radiation therapy. Controversy exists regarding the benefit of androgen deprivation therapy in patients with intermediate-risk disease, in the absence of pertinent clinical trials. Results of RTOG 9408 should be available in the near future.

Other questions regarding the use of androgen deprivation therapy that still require elucidation are regarding the role for androgen deprivation therapy in the setting of radiation dose escalation, and how androgen deprivation therapy should be used in men with significant comorbidities.

Gynecomastia and related symptoms have been prevented in approximately 80% of patients treated with superficial x-rays (10-Gy single dose) using small appositional portals (30, 44).

We have used tangential portals with cobalt 60 or 4-MV photons or appositional electron beam (9 to 12 MeV) portals delivering a 12- to 16-Gy midplane dose to each breast in 4 fractions. The customary field size is 8 × 8 cm or a circle 8 cm in diameter.

The entire breast tissue must be irradiated before orchiectomy or initiation of estrogen therapy; otherwise, glandular hyperplasia is not preventable.

Various techniques have been used, ranging from parallel anteroposterior (AP) portals with a perineal appositional field to lateral portals (box technique) or rotational fields to irradiate or supplement the dose to the prostate (6).

In recent years, three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3-D CRT) and intensitymodulated irradiation techniques (IMRT) have been increasingly used (29, 42

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree