Primary aldosteronism (PA) is uncommon in pregnancy, with fewer than 64 cases reported in the medical literature; most of these reported patients had aldosterone-producing adenomas (APAs). PA can lead to intrauterine growth retardation, preterm delivery, intrauterine fetal demise, and placental abruption. Case-detection testing for PA in a pregnant woman is the same as for nonpregnant patients: morning blood sample for the measurement of aldosterone and renin. The combination of suppressed renin and an aldosterone level >10 ng/dL is a positive case-detection test for PA. If spontaneous hypokalemia is present in the woman with high plasma aldosterone concentration (≥20 ng/dL) and suppressed renin, confirmatory testing is not needed. In a normokalemic woman with a positive case-detection test, confirmatory testing should be pursued. However, the captopril stimulation test is contraindicated in pregnancy, and the saline infusion test may not be well tolerated. One option is measurement of sodium and aldosterone in a 24-hour urine collection on an ambient sodium diet. Subtype testing with abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without gadolinium is the test of choice. Computed tomography (CT) and adrenal venous sampling (AVS) should be avoided in pregnancy. In patients with vigorous PA who are less than 35 years old and have a clear-cut, unilateral adrenal adenoma on MRI, AVS is not needed. The type of treatment for PA in pregnancy depends on how difficult it is to manage the hypertension and hypokalemia. If the patient is in the subset of those who have a pregnancy-related remission in the degree of PA during pregnancy, then surgery or treatment with a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) can be avoided until after delivery. However, if PA accelerates during pregnancy and hypertension and hypokalemia are marked, then surgical and/or targeted medical intervention with a MRA is indicated. Unilateral laparoscopic adrenalectomy during the second trimester can be considered in those women with confirmed PA and a clear-cut unilateral adrenal macroadenoma (>10 mm).

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman (gravida 2, para 1) was initially seen elsewhere at 12 weeks of gestation for increasing weakness and fatigue. She was hypertensive and hypokalemic. The plasma aldosterone concentration was >20 ng/dL and the plasma renin activity was suppressed. She was treated with potassium chloride and spironolactone. Because of worsening hypertension (160/105 mmHg), at 28 weeks of gestation she was referred to Mayo Clinic.

INVESTIGATIONS

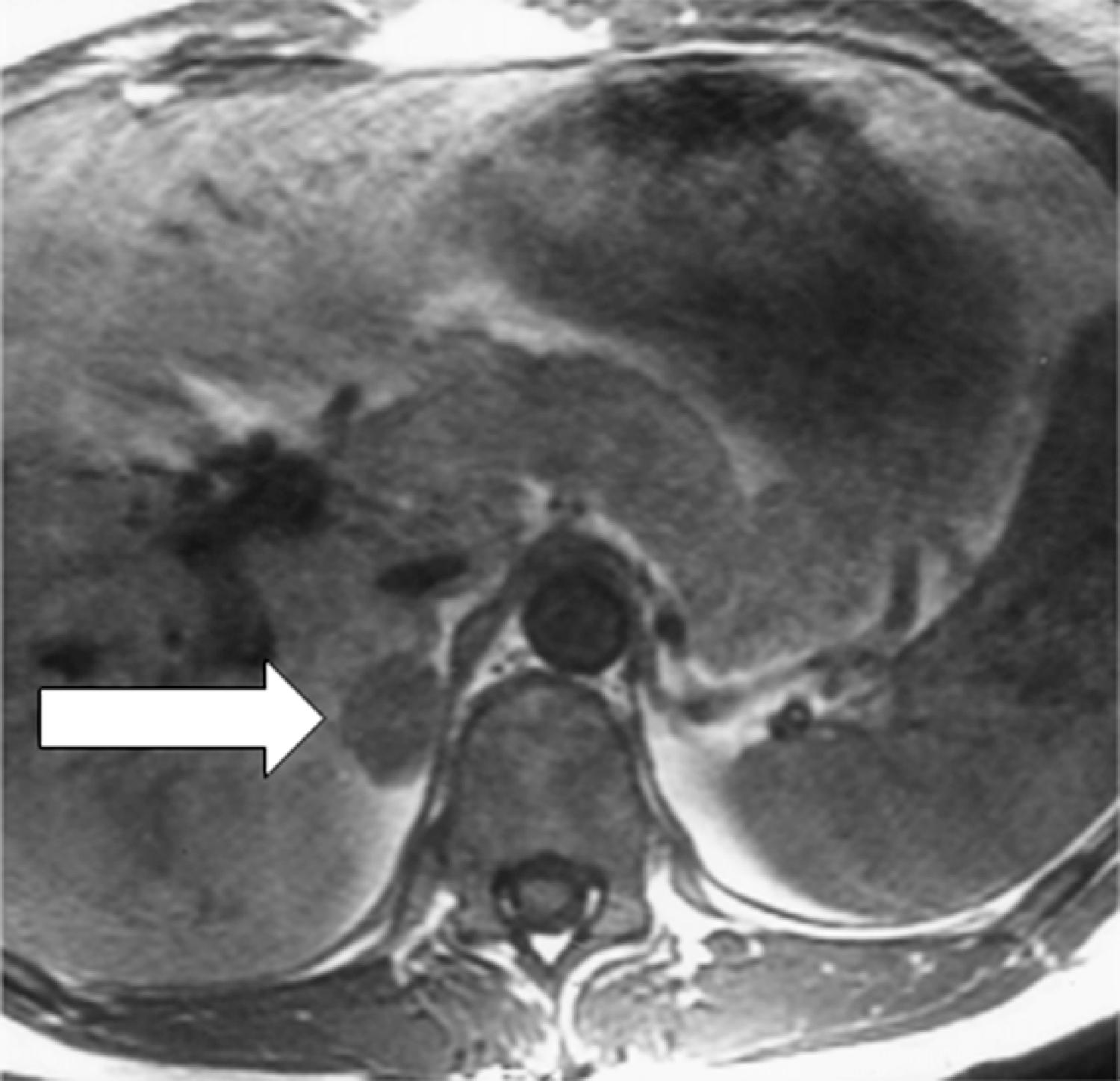

Laboratory studies at Mayo Clinic were diagnostic for PA. The plasma aldosterone concentration was 230 ng/dL (normal, <21 ng/dL) and the plasma renin activity was suppressed. An abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without gadolinium detected a 3.0 × 2.0 × 2.0–cm right adrenal mass with imaging characteristics consistent with an adenoma ( Fig. 100.1 ).

TREATMENT

Treatment with spironolactone was discontinued. Despite additional antihypertensive medications, over the next 4 weeks she had worsening hypertension (165/115 mmHg) and proteinuria (24-hour urine protein was 4800 g). She subsequently underwent induction of labor at 32 weeks of gestation for superimposed preeclampsia. She delivered a 1705-g male infant. Examination of the genitalia was normal. The infant required 15 days of neonatal intensive care for respiratory distress syndrome and nutritional support. At 2 months postpartum the mother underwent right adrenalectomy without complication. Pathology showed a 2-cm benign adrenocortical adenoma consistent with an APA.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

At 1 month after operation the plasma aldosterone concentration was <1 ng/dL. At last follow-up, 1 year later, she was normotensive and normokalemic. She did not require potassium supplementation or antihypertensive medications.

Discussion

A unique feature of PA during pregnancy is that the degree of disease may be either improved or aggravated. In some women with PA, the high blood levels of pregnancy-related progesterone are antagonistic at the mineralocorticoid receptor and partially block the action of aldosterone; these patients have an improvement in the manifestations of PA during pregnancy. , In other pregnant women, increased expression of luteinizing hormone choriogonadotropin receptor has been documented in APAs that harbor β-catenin mutations, and the degree of hyperaldosteronism is aggravated by the increased pregnancy-related blood levels of human chorionic gonadotropin. ,

The optimal treatment for PA in pregnancy depends on how difficult it is to manage the hypertension and hypokalemia. If the patient is in the subset of patients who have a remission in the degree of PA, then surgery or treatment with a MRA can be avoided until after delivery. However, if hypertension and hypokalemia are marked, then surgical and/or medical intervention is indicated. Unilateral laparoscopic adrenalectomy during the second trimester can be considered in those women with confirmed PA and a clear-cut unilateral adrenal macroadenoma (>10 mm).

Spironolactone crosses the placenta and is a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy category C drug because feminization of newborn male rats has been documented. However, there is only one human case in the medical literature where treatment with spironolactone in pregnancy led to ambiguous genitalia in a male infant; this occurred in a woman treated with spironolactone for polycystic ovary syndrome prepregnancy and through the fifth week of gestation. Eplerenone is an FDA pregnancy category B drug. Therefore, for those pregnant women who will be managed medically, the hypertension should be treated with standard antihypertensive drugs approved for use during pregnancy. Hypokalemia, if present, should be treated with oral potassium supplements. For those patients with refractory hypertension and/or hypokalemia, the addition of eplerenone may be cautiously considered. ,