CHAPTER 41 Preventive Healthcare in Children

Introduction

Children in immigrant families are the fastest growing segment of the pediatric population in the United States. From 2002 to 2004, on average, 156 000 children under the age of 16 years legally immigrated to the United States each year and approximately 22 000 foreign-born children were adopted into US families annually.1 The number of children entering the country illegally is unknown, but has been estimated at 30 000 per year.2 Over 75% of children in the United States living in immigrant families were born in the United States.3 These US-born children have similar health disparities to those experienced by foreign-born children. From 1990 to 1997, the number of children in immigrant families grew by 47%, compared to a 7% increase in children of non-immigrant families.3 In 1997, 14 million, or nearly one in every five children living in the US, were immigrants or had immigrant parents.3 One in every four children who live in a low-income family has immigrant parents.4

Children in immigrant families face the same health concerns as the general pediatric population. In addition, these children are confronted with multiple factors before, during and after immigration that increase their susceptibility to several health conditions. These factors are complex and interrelated. Categorizing these factors into four broad topics may help form a framework of immigrant children’s preventive healthcare needs (Table 41.1). These categories include: (1) preexisting health inequities, (2) acculturation, the process of assimilating into a new culture, (3) unique environmental exposures and injuries, and (4) ‘life-course theory,’ a developing understanding of how childhood events and growth patterns may influence the development of chronic illnesses later in life.

Table 41.1 Key topics in pediatric immigrant preventive health

It is important to remember while examining these topics that children of immigrant families face obstacles in receiving healthcare of any kind, let alone preventive care (Table 41.2). Perhaps the most obvious barrier is lower rates of health insurance. Among foreign-born children with legal citizenship, only 48% were found to have health insurance and only 66% had an identified regular source of healthcare in 1997, compared to 80% and 92%, respectively, among native-born children of the working poor.5 The disparities are even greater among specific immigrant groups. The largest minority group of children in the United States is Hispanic. Mexican-Americans comprise the largest proportion of this diverse population.6 In 1995, Mexican-American adolescents were less likely than adolescents of Cuban, Dominican, Puerto Rican, or Central and South American origin to have had a routine physical examination, highlighting significant variation in healthcare access within the broad ethnic group of Hispanic-Americans.7 The low healthcare utilization of Mexican-American adolescents is at least partially explained by poor insurance coverage. Only 36% of first-generation Mexican-American children were found to have medical insurance between 1988 and 1994. Although second- and third-generation Mexican-American children had higher rates of coverage, they were still more likely to be uninsured as compared to non-Hispanic black and white children under 16 years old.6

Table 41.2 Barriers to preventive healthcare

These figures have likely worsened in recent years due to changes in Medicaid coverage. For example, the prevalence of uninsured foreign-born children living with low-educated single mothers has increased by 13.5% in response to the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, without a corresponding increase seen among US-born children.8 Even in states that have responded with programs to provide insurance to all low-income children, many children in immigrant families have not been insured due to various obstacles experienced by their parents.9

In 2000, after adjusting for insurance coverage, Asian, Hispanic, and black children were less likely than white children in the US to have a usual source of care, health professional or doctor visit, and dental visit in the past year.10 Therefore, other important barriers, in addition to lack of health insurance, are present. One of these obstacles is the significantly lower awareness among immigrant parents of healthcare and other support services available to their families in the US.11 The same holds true in Canada despite universal healthcare insurance.12 This decreased awareness of health-related resources may stem from linguistic isolation, defined as the lack of anyone over 14 years of age in a household able to speak English.11,12 In addition to decreasing awareness, linguistic isolation, present in over a quarter of all immigrant families with school-age children,13 impairs parents’ ability to make medical appointments, understand health recommendations, and advocate for the needs of their children. Outreach efforts are essential to eliminate this isolation.11

Additional obstacles to care exist. Over 10% of Hispanic parents may not bring their children in for care if they feel the medical staff is not familiar with their culture.14 In addition, parental stress associated with resettlement,15 as well as fear of apprehension of family members with illegal immigration status,13 may cause parents to avoid healthcare visits. Finally, children who have immigrated unaccompanied by adults, several thousand of whom enter the United States every year, are especially unlikely to access healthcare.2,15

Preexisting Health Inequities

As suggested by Jenista, in a thorough review of the topic,2 the key components of new-arrival screening of immigrant children should include: (1) infectious disease screening, (2) a review and update of immunizations, (3) evaluation of mental health needs, (4) inspection for dental problems, (5) screening for nutritional disorders, (6) assessment of development, (7) screening for possible environmental exposures, (8) vision and hearing screening, (9) consideration of medical conditions common in specific ethnic groups, and (10) a review or request for any pertinent medical records. Most of these topics of new-arrival screening are discussed in other chapters (Table 41.3). It is important to remember that many of these components, such as mental and dental health, nutritional disorders, developmental disorders, and environmental exposures need to be regularly followed well beyond the new-arrival period. In this section, nutritional disorders in new pediatric immigrants are reviewed.

Table 41.3 Preventative interventions at time of initial healthcare visit(s)

Adapted with permission from Pediatrics in Review, Vol. 22, Page 424, Copyright © 2001 by the AAP.

Chronic malnutrition

Prior to immigration, children, especially those who have come from refugee camps, are at risk for chronic malnutrition (Box 41.1). Chronic malnutrition typically results from a combination of inadequate intake of micro- and macronutrients, recurrent acute infections, chronic infections including intestinal parasitosis, and occasionally a poor mother–child bond.16 After nutritional reserves are depleted chronic malnutrition leads to impaired height growth, termed ‘stunting.’ The long-term consequences of stunting include delays in motor and mental development, decreased work capacity, and increased susceptibility to infections.17

To screen for malnutrition, it is imperative to check the height and weight of all newly arrived children. Chronic undernutrition can be screened for by plotting a child’s height-for-age on growth reference curves. Stunting is technically defined as a height-for-age value less than two standard deviations (−2 Z-scores) below the mean of the reference population. However, since most growth charts used in clinical practice are presented as percentiles, this cutoff is equivalent to the 2.3 percentile, lower than the commonly used fifth percentile threshold used to detect poor growth. (Percentiles can be converted to Z-scores using the dataset Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts) Often, an immigrant child’s date of birth is not known, making nutritional assessment difficult. In such circumstances, initially, the reported age on accompanying paperwork should be accepted, unless there is an obvious discrepancy. Determination of true age should be delayed, ideally up to 1 year, to allow time for catch-up growth and development. At that time, age can be estimated by a combination of bone and dental ages, pubertal stages, maturity, and school performance.2

Stunting was detected in 143 (8%) of 1767 refugee children arriving in Massachusetts between 1995 and 1998 from locations all around the world. The chronically malnourished children came primarily from Africa, Near Eastern Asia, and East Asia, in which prevalence of stunting was 13%, 19%, and 30%, respectively.18 Stunting was associated with both infection with intestinal parasites and origination from developing countries. However, when both of these variables were included in a multivariate analysis only origination from a developing country remained a significant predictor of stunting. An earlier study suggested that significant variation in rates of stunting occurs in children from different resource-poor countries. In the early 1980s, high levels of stunting (34% of boys and 33% of girls) were detected in newly arrived children of Southeast Asian ethnicities (Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian). Moderate levels of stunting were seen in children from China and the Philippines. Children of Latin American origin had even lower levels (9% of boys and 8% of girls).19 This suggested that, in addition to economic conditions in countries of origin, life circumstances, such as time spent in refugee camps, is likely an important determinant of chronic malnutrition.

In the past there have been some requests for the development of separate growth reference curves for people of different ethnicities. However, it has been shown that even among highly stunted Southeast Asian children, significant linear catch-up growth typically occurs after immigration, allowing these children to approach or reach the heights of age-matched native-born children of all ethnicities.19,20 Close monitoring is needed to ensure that linear catch-up growth occurs. If it does not occur, underlying chronic infections such as tuberculosis, continued food insecurity, and parental or child mental health issues should be considered.

Achieving adequate catch-up growth does not require intake of energy-dense foods in large amounts. In fact, such foods may be detrimental to future health as discussed below in the acculturation and life-course theory sections. Rather, supplementation of a healthy diet with micronutrients has been shown to be effective and sufficient.16 Interestingly, rapid catch-up growth resulting in hormonal changes has been hypothesized as a possible explanation of precocious puberty occasionally seen in immigrant children soon after arrival. This phenomenon has been documented most frequently among internationally adopted girls.21

Acute malnutrition

Acute undernutrition leads to poor weight gain and is detected by a low weight-for-height, termed ‘underweight or wasting.’ Wasting, defined as values two standard deviations below the mean, or below the 2.3 percentile, is seen less often than stunting in newly arrived refugee children. Children under the fifth percentile are underweight. Among a group of children from Southeast Asia with a prevalence of stunting >30%, only 3% of boys and no girls showed wasting upon arrival in the 1980s.19 In Massachusetts, only 23 (2%) of 964 refugee children had wasting. Of these, 83% came from Africa or East Asia. After adjusting for other variables, anemic children were 15 times more likely than nonanemic children to have wasting. Also, older children and those from developing countries were at greater risk of acute malnutrition.18 Information on treating acute malnutrition in immigrant children is lacking. Clearly, based on studies in developing countries, higher protein diets with at least a moderate proportion of fat are indicated. However, parents should be educated that this type of high-calorie diet is only temporary and that continued overnutrition after adequate catch-up weight gain is achieved may predispose children to multiple chronic illnesses.

Anemia

Iron deficiency is the likely cause of anemia in most pediatric immigrant groups. This is supported by the very high rates of iron deficiency and anemia seen among children in refugee camps abroad.22 Among the diverse groups of refugee children arriving in Massachusetts between 1995 and 1998, 153 (12%) of 1247 children were anemic.18 The prevalence of anemia varied significantly by region and age. Children from Africa had the highest prevalence (31%), while those from the former Soviet Union had the lowest (10%). Children under 2 years of age from each region had the highest burden of anemia. Fifty percent of African children younger than 2 years of age were anemic. Young adolescents also were relatively more likely to be anemic. If untreated, iron deficiency may lead to cognitive impairments, behavioral problems, and increased susceptibility to lead poisoning.23 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has suggested starting all newly arrived refugee children on multivitamins with iron upon arrival.24 It is important to remember that genetic hemoglobinopathies, thalassemias, and enzyme deficiencies may also account for many cases of anemia, especially among children from Southeast Asia (see Ch. 46).25

Overweight and obesity

Obesity, defined as an excess of adipose tissue, is difficult to test for. The costs and availability of the gold-standard methods of quantifying adipose tissue, such as dual energy X-ray absorptiometry and underwater weighing, are prohibitive. The simple body mass index (BMI) [weight(kg)/height(m)2] is commonly used to screen for obesity. However, this tool is only a surrogate for adiposity and it has several unique limitations for children and adolescents. In the pediatric age groups BMI varies by age, gender, and maturation. The most commonly used BMI classification system in the US is based on the findings from the US National Health and Nutrition Surveys (NHANES) and charts can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts.26 In this system, adopted by the World Health Organization, children are classified by their sex- and age-specific percentile. BMI values greater than or equal to the 85th and less than 95th percentiles denote ‘overweight’ (or ‘at risk for overweight’ by the CDC) and values greater than or equal to the 95th percentile indicate ‘obese’ (or ‘overweight’ by the CDC).27 In this chapter, these cutoffs will be referred to as ‘overweight’ and ‘obese’ for simplicity.

Children from Eastern Europe may be particularly likely to arrive overweight. In the Massachusetts study of newly arrived refugee children, 15% of 157 and 14% of 374 adolescents from the former Yugoslavia and Soviet Union, respectively, were overweight or obese. Interestingly, a significant positive association between dental caries and BMI values equal to the 85th percentile was noted (OR = 2.6, 95% CI = 1.2–4.4).18 This may be explained by higher intake of refined sugars in children from more developed areas of the world.28

Acculturation

Despite the preexisting health inequities immigrant children may have at the time of arrival, it is often noted that, on average, new immigrants of all ages have better health status as compared to the native population. This counterintuitive finding has been called the ‘healthy migrant effect’ and the ‘the epidemiologic paradox.’29 (see Ch. 3). This phenomenon may be associated with the lower rates of low birth weight infants,30 early postnatal mortality,31 asthma,32 and obesity33 seen in new immigrant children. Reports have also shown that recent adolescent immigrants are less likely to take part in high-risk behaviors.29 The underpinnings of these findings may be related to the retention of traditional, often healthier, diets and strong support networks within families and immigrant communities.29 However, part of the ‘healthy migrant effect’ may also be explained by underreporting bias. For example, although specific illnesses such as ear infections and pneumonia have been reported to occur less often among newly arrived immigrant children, these same children have far fewer healthcare visits while also having the lowest level of perceived health by parents.6

Unfortunately, the ‘healthy migrant effect’ is short lived. As immigrant children and their families assimilate into the culture of their new country, through a process know as acculturation, their health status begins to deteriorate and, in time, will often fall below that of the general population. Acculturation can be defined as the ‘process of learning and incorporating the values, beliefs, language, customs and mannerisms of the new country immigrants and their families are living in, including behaviors that affect health such as dietary habits, activity levels and substance use.’34 Acculturation can be measured in various ways such as language preference, English proficiency, level of ethnic pride and identity, and ethnicity of neighbors and close friends.29 Several acculturation scales have been validated. For example, the Acculturation, Habits, Interests and Multicultural Scale for Adolescents (AHIMSA) has been designed to quantify the degree of assimilation into the new culture, separation from the old culture, and integration of and marginalization from both cultures.35

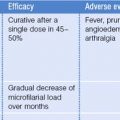

It is disconcerting that through the act of fleeing negative life circumstance, immigrants are at risk of developing new problems. The aspects of health that are negatively affected by acculturation are often the same as those in which new immigrants fare relatively well. Acculturation has been reported as a potential risk factor for multiple unhealthy behaviors including smoking,34,36 alcohol37,38 and other drug use,39 high-risk sexual activity,40 violence,41 suicidal ideation,42 physical inactivity,43 and fast-food consumption.43 Parental acculturation leading to pressures to bottle-feed their toddlers on demand has been suggested as an explanation of high rates of iron deficiency seen in Hmong-Americans.44 The well-documented effects of acculturation on the development of obesity and high-risk behaviors will be reviewed below (Table 41.4). In addition, possible connections between acculturation and asthma will be discussed briefly.

Table 41.4 Effects of acculturation on obesity and high-risk behaviors

| Obesity | High-risk behaviors |

|---|---|

Overweight and obesity

Obesity among children has reached epidemic proportions in developed countries throughout the world.45 The associated health effects of childhood obesity are numerous and include reduced self-esteem, hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, sleep apnea, asthma, cholelithiasis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, genu varum and slipped capital femoral epiphysis.27,46 Obese 4-year-old children and adolescents have an estimated 20% and 80% likelihood, respectively, of remaining obese in adulthood.46

In the United States, the prevalence of overweight children and adolescents has doubled from the late 1970s to 1999–2002.47 The most current data indicate 23% and 31% of children aged 2–5 and 6–19 years-old in the US are either overweight or obese, respectively (BMI for age ≥ 85th percentile).48 The prevalence varies considerably by ethnicity. Among Mexican-American youths between 6- and 19-years-old, 40% are overweight or obese. This is significantly higher than rates of 35% among non-Hispanic black children and 28% among non-Hispanic white children of the same age group (p < 0.05).48 Socioeconomic factors such as family income and education can only partially explain these differences in overweight and obesity among both young children and adolescents.49,50 Acculturation has been identified as an additional factor in overweight and obesity disparities.

In the complex process of acculturation, children and adolescents are likely to adopt attitudes and behaviors considered to be the norm for areas in which they are living. Immigrants to the United States often transition from traditional foods and activities to those that are considered more ‘American.’43 Unfortunately, these ‘American’ behaviors such as fast-food consumption and physically inactive pastimes, such as television viewing, are known risk factors for obesity. Among adolescents of Mexican, Cuban, and Puerto Rican ethnicity, significant differences in diet have been noted between first- and second-generation immigrants. The less acculturated first-generation immigrants were more likely to maintain traditional diets containing plentiful rice, beans, fruits, and vegetables, as compared to second-generation adolescents. In addition, second-generation Mexican-American adolescents were more likely to eat fast food as compared with their first-generation counterparts.51 Immigrants of Asian ethnicity tend to eat less fish, vegetables, and whole grains and more snack foods, fast food, processed meats, and fat after living in the United States.43 A recent study evaluating the effects of acculturation on the level of physical activity and fast-food consumption among 1385 Hispanic and 619 Asian-American adolescents living in Southern California found that, after controlling for confounding variables, acculturation, measured by the AHIMSA tool, was negatively associated with physical activity (p = 0.001) and positively associated with fast-food consumption (p = 0.001).43

These acculturation-associated effects on diet and physical activity are consistent with findings that second-generation Asian-American and Hispanic-American adolescents are significantly more likely to be obese as compared to foreign-born adolescents of similar ethnicity.33 This intergenerational difference is most profound for Asian-Americans in whom the percentage of overweight or obese adolescents increased from 12% among first-generation immigrants to 27% among second-generation immigrants, significantly above the overweight and obesity prevalence of 24% seen among the 7726 US non-hispanic white adolescents included in the study.

There is some evidence that lower acculturation levels among Hispanic-American parents may protect their children from obesity. Although obesity was not specifically assessed in an analysis of 2985 4–16-year-old Hispanic children, investigators did find that children of less-acculturated parents had a lower intake of fat and other macronutrients associated with obesity.52 Children from the lowest-income households had a significantly increased likelihood of experiencing food insecurity. Food insecurity, which is potentially a common occurrence among many immigrant families, may be associated with obesity by leading families to establish diets with inferior nutritional quality.53 However, among the lowest-income families, a lower level of parental acculturation partially negated the effect of food insecurity.52

In contrast, among school-aged Chinese-American children three variables have been found to correlate with the likelihood of having a higher BMI: older age, poor communication between children and parents, and less authoritative parenting style. The authors of this study suggested that the more acculturated mothers, who also tended to have a more authoritative parenting style, may be more equipped to utilize healthcare resources and may be more aware of health issues related to being overweight.54

To date, very limited data are available on the effects of acculturation on obesity among the more recent immigrant groups from sub-Saharan Africa. The information available indicates that the interaction between acculturation and traditionally held concepts of health may work synergistically among this group of immigrants leading to a high prevalence of obesity.55 Within many resource-poor countries, including many in sub-Saharan Africa, obesity is not perceived as an adverse health condition. In these countries being heavy is often seen as a marker of success, wealth, and good health.55 In many parts of Africa, luxury foods, or ‘food of white people,’ are desired as a means of achieving larger body sizes.55 These foods, such as meats, soft drinks, butter, sugar, and mayonnaise, are often expensive in resource-poor areas, but are much more affordable after immigrants settle in developed countries. It has been postulated that increased availability and increased exposure to advertising of such foods combined with decreased physical activity in developed countries may explain high rates of obesity among refugee children from sub-Saharan Africa in Australia.55 Healthier fruits and vegetables are often viewed as food of the poor, a sentiment that may persist after emigration.55

Prevention of obesity has become a key aspect of pediatric health maintenance as the childhood and adolescent obesity epidemic continues to worsen. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends regular BMI monitoring of children at risk for obesity ‘by virtue of family history, birth weight or socioeconomic, ethnic, cultural, or environmental factors.’46 Clearly, acculturating children of immigrant families are exposed to unique cultural factors mandating close monitoring. Even before excessive weight gain is detected in these children their parents should be routinely reminded, in a culturally sensitive manner, of the importance of healthy eating patterns and physical activity. Parents should be encouraged to offer fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy products and whole grain foods, to set limits on unhealthy food choices, to model healthy food choices, to limit television viewing and video time to under two hours per day, and to allow for unstructured play time daily.46 The CDC suggests that children and adolescents incorporate one hour of moderate activity into their daily schedules. Healthcare providers may be able to make an even more significant contribution by advocating for healthy foods in schools and for opportunities and facilities for regular physical activity.

In general, the BMI based on NHANES data has a high specificity for overweight (91.5% for boys and 92.4% for girls) and obesity (96.9% for boys and 97.3% for girls) relative to percent-body-fat measurements.56 However, the BMI is likely to overestimate (high false positives) obesity in stunted children. Several reports have found a high prevalence of both stunting and overweight or obesity in Hmong children in the United States.57 The paradoxical finding of simultaneous stunting and obesity has been reported among children undergoing rapid nutrient transitions, in which weight is gained but linear growth is limited.58 Nevertheless, using the BMI, triceps skin folds, and body fat percentage, the prevalence of overweight or obesity among 72 Hmong-American children aged 4–11 years was 42%, 29%, and 25%, respectively.57 Therefore, to avoid overestimations of obesity, it has been suggested that among children with short stature those with high BMIs should have additional testing such as triceps skin fold or body fat percentage measurements. A new BMI system, endorsed by the International Obesity Task Force,59 based on data collected from large surveys from Brazil, Great Britain, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Singapore, and the United States, has a higher specificity for obesity as compared to the NHANES-derived BMI at the expense of decreased sensitivity.56

Risk-taking behaviors

Unacculturated adolescents may be protected from harmful behaviors by ethnic isolation. These individuals often are members of non-English-speaking families and live among and socialize largely with people of the same ethnicity, thus limiting their exposure to ‘American’ norms of rebellious behaviors. Also, less-acculturated youths are more likely to be primarily influenced by parents and family rather than peers.34 As adolescents’ English language skills improve they are more likely to form peer groups with more acculturated immigrant and/or native-born youths, people who are more likely to perceive certain risk behaviors as normative.34 The US-born group into which an immigrant child assimilates frequently is similar to his or her ethnicity and socioeconomic level. Often, these native-born groups have high rates of risk-taking behaviors. For example, both immigrant and native-born Latino adolescents living in Northern California were found to have similar high rates of substance use, unintended pregnancy, and violence, as compared to native non-Hispanic white adolescents.60

Acculturation gaps can also lead to role reversal in which children become ‘cultural brokers’ and are relied upon by their parents to help the family navigate many aspects of daily life. Among adolescent girls from Russia, 89% reported performing cultural brokering, with even higher rates among those with mothers who spoke little English.61 Higher levels of cultural brokering were associated with higher adolescent stress, more reports of problems at home and with friends, and lower feelings of school membership. Cultural brokering, in addition to the stresses of trying to assimilate with peers, and stresses associated with low socioeconomic status as part of an immigrant family, may be considered collectively as acculturative stress.62 If extreme, acculturative stress may lead to depression and suicidal ideation among adolescents.42 It may also contribute to maladaptive substance use as discussed below.

The three aspects of acculturation described above: increasing exposure to ‘mainstream’ behaviors, poor parent–child communication, and acculturative stress, have been shown to affect substance use among adolescents of immigrant families. The effect of increasing exposure to ‘mainstream’ behaviors is illustrated by a study of Hispanic and Asian-American children aged 8–16 years. Among these youths, the likelihood of ever smoking was found to be strongly associated with the type of language spoken in their homes. Those who spoke only English at home were twice as likely to have tried smoking as compared with those who only spoke other languages (for Asians OR = 1.94, 95% CI 1.19–3.19; for Hispanics OR = 2.07, 95% CI 1.45–2.97).34 Increases in smoking were noted for each incremental increase of English usage. In addition to smoking, higher levels of English usage were also associated with a higher perceived access to cigarettes, a higher likelihood of having a best friend who smokes, more frequent offers for cigarettes from friends, and a decreased perceived ability to refuse cigarette offers. These additional associations with English usage likely represent some of the ways in which acculturation increases the risk of smoking and other substance use by removing the protections associated with linguistic and ethnic isolation. Others have found similar correlations between language usage at home and the likelihood of using marijuana alone, or in conjunction with cigarettes and alcohol, among Hispanic-American adolescents of primarily Puerto Rican, Dominican, Colombian, and Ecuadoran origins.39

The second consequence of acculturation that may lead to substance use is change in the quality of communication between immigrant parents and their children. Among Hispanic migrant adolescents, this was found to be a significant predictor of past alcohol or cigarette use. Adolescents who were satisfied with the quality of communication they had with their parents were 48% less likely to have ever smoked (OR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.31–0.87) and 27% less likely to have ever drunk alcohol (OR = 0.63, 95% CI 0.38–0.98). The authors suggest that acculturation gaps between adolescents and parents may impair communication, thereby impairing the ability of parents to positively influence behaviors.63

Similar findings on the effects of communication have been reported for alcohol use by adolescent Asian-Americans. Among those with low parental involvement, highly acculturated youths were 11 times more likely to have used alcohol as compared to the least acculturated youths. However, among adolescents with moderate or high levels of parental involvement, there was no variation in alcohol use by degree of acculturation.64

Thirdly, acculturative stress may predispose adolescents to substance use. This is supported by a study of 8th and 10th grade students from Massachusetts. Although US-born adolescents were more likely to use alcohol or marijuana as compared to immigrant adolescents, especially compared to immigrants that had arrived more recently, the recent immigrant group, defined as living in the United States for less than 6 years, was more likely to be affected by factors that may predict future high-risk behaviors. These factors include: greater peer pressure to partake in substance use, sex, and violence; less parental disapproval of these behaviors; and less confidence in the ability to refuse substances that may be offered to them.65 These stresses may lead to early substance use in some immigrant youths. For example, binge alcohol drinking has been identified as a possible coping mechanism among some recently immigrated Mexican-, Cuban-, and Puerto Rican-American adolescents of Spanish-speaking homes who are confronting new acculturative stresses.62

An important window of opportunity exists in which targeted efforts may decrease the risk of future substance use by both foreign-born children and unacculturated native-born children. Foreign-born adolescents who have lived in the US for fewer than 5 years have significantly lower rates of alcohol consumption and use of cigarettes, marijuana, and other illicit drugs as compared to US-born youths.36 However, by the time foreign-born adolescents have lived in the US for 10 years, their substance use mirrors that of the native-born population.36 Similar timelines would likely be seen among unacculturated native-born children of immigrant families.

To best help older children and adolescents avoid or at least reduce the consequences of high-risk behaviors, healthcare providers should consider addressing the issues related to acculturation during office visits. Parents and children should be familiarized to the differing rates of acculturation within a family with a goal of improving parent–child communication. Discussing acculturative stress with adolescents may help them understand that such stresses are common. However, even the most skilled clinician will be unable to counterbalance the powerful effects of acculturation on high-risk behaviors in the office. Therefore, it is important to advocate for and help families in accessing community and school-based programs that address these issues. Outreach programs involving both parents and adolescents have shown promising results. For a group of Hispanic migrant adolescents, just eight evening sessions, three of which were also attended by their parents, focusing on the effects of smoking and alcohol and the development of refusal skills and parent–child communication skills, led to improvements in parent–child communication that were estimated to translate into a 10% decrease in susceptibility to future tobacco or alcohol use.66

In addition to substance use, acculturation may increase the likelihood of sexual activity among immigrant youths. For example, while Hispanic-American girls in 7th to 12th grade living in Arizona were overall more likely to have had sexual intercourse than age-matched non-Hispanic white girls (OR = 1.4, 95% CI 1.21–1.63), those who spoke primarily Spanish were significantly less likely to have been sexually active compared to non-Hispanic white adolescents (OR = 0.59, 95% CI 0.42–0.82).67 As with substance use, the effects of acculturation gaps on parent–child communication may be important risk factors for high-risk sexual activity among adolescents. This has been identified as a major barrier to effective communication about sex between Filipino-American teenagers, a population with high pregnancy rates compared with other Asian and Pacific Islander groups, and their parents. The acculturated adolescents felt that open discussions were necessary to learn about their parents’ values in regards to sex. However, parents and grandparents felt that these ‘values were transmitted best through traditional Filipino respect for parents’ and often avoided discussion with their children.68 The format of community-based family sessions may help to facilitate needed discussions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree