PREMATURE MENOPAUSE

Part of “CHAPTER 100 – MENOPAUSE“

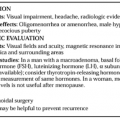

Premature ovarian failure is the onset of menopause before age 35 years, and is diagnosed by finding elevated plasma FSH levels. The reported incidence of this condition among women with amenorrhea varies from 4% to 10%. Women who pass through menopause at a younger age have the typical symptoms of estrogen deficiency, including vasomotor flushes and genital atrophy. However, it may not be permanent, and some women may ovulate again.6,6a

The causes of premature ovarian failure are many (see Chap. 96 and Chap. 102). Genetic abnormalities, usually associated with deletions of the long arm of the X chromosome or mosaicism, may lead to depletion of oogonia.7,8 Autoimmune disorders, either alone or in association with other autoimmune endocrine disorders such as Addison disease, may lead to ovarian failure. Radiation or

chemotherapy can cause ovarian failure. There is evidence that chemotherapy administered before puberty and in the absence of radiation therapy does not affect the ovaries.9 In a condition known as Savage syndrome, the ovarian follicles are resistant to the gonadotropins. The plasma gonadotropin levels are elevated. This disorder could be caused by a gonadotropin receptor or postreceptor defect within the ovary. Galactosemia is associated with primary ovarian failure; in this case, it is thought that an abnormal metabolite interferes with postreceptor activity. Another form of premature ovarian failure is surgical menopause.

chemotherapy can cause ovarian failure. There is evidence that chemotherapy administered before puberty and in the absence of radiation therapy does not affect the ovaries.9 In a condition known as Savage syndrome, the ovarian follicles are resistant to the gonadotropins. The plasma gonadotropin levels are elevated. This disorder could be caused by a gonadotropin receptor or postreceptor defect within the ovary. Galactosemia is associated with primary ovarian failure; in this case, it is thought that an abnormal metabolite interferes with postreceptor activity. Another form of premature ovarian failure is surgical menopause.

In all of these cases, hormone-replacement therapy should be considered. Women with premature ovarian failure are vulnerable at an early age to develop genital atrophy, osteoporosis, vasomotor symptoms, and probably heart disease.

GENITAL ATROPHY

VULVA

The postmenopausal vulva has little subcutaneous fat and elastic tissue, resulting in a narrower opening, and sparser and coarser pubic hair than the premenopausal vulva. The labia majora shrink more than the labia minora, so that the relative proportions of the prepubertal organ are restored. The Bartholin glands secrete less fluids for lubrication, and vaginal dryness is often a problem. Moreover, the vulva may become more pruritic.

VAGINA

The postmenopausal vaginal mucosa loses its papillae, the rugae flatten, and the vaginal walls become smoother and thinner. These changes often cause dyspareunia, burning, and occasional bleeding through breaks in the vaginal wall. Forwomen who have ceased having intercourse, the vagina may become stenotic.10

With decreasing estrogen production, the vaginal glycogen content diminishes and the pH is increased, leading to inhibition of lactobacilli, which in turn permits other organisms to grow, including streptococci, staphylococci, diphtheroids, and coliforms. These bacteria are often responsible for vaginal discharge and vaginal infections after menopause. In such cases, antibiotics and other preparations provide temporary relief but are not curative. Estrogen treatment is more effective in providing long-term resolution of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia.

Some women passing through the menopause experience decreased intensity and duration of sexual response. However, many, if not most, postmenopausal women continue to be sexually active. If dryness is a problem, estrogens may be very helpful.11 Nonhormonal vaginal lubricants (such as Replens, Columbia Pharmaceuticals) may also be useful.

URETHRA

The urethra has the same biologic origin as the vagina (the urogenital sinus) and also undergoes postmenopausal atrophy. Some women experience problems with dysuria and frequency in the absence of infection; estrogen treatment is effective in providing relief.

UTERUS

With estrogen depletion, the postmenopausal uterus becomes smaller and firmer. Vascularity is reduced, and uterine leiomyomas decrease in size. Inner migration of the squamocolumnar junction of the cervix occurs; thus, it may become more difficult to diagnose cervical cancer. The fallopian tubes show deciliation and decreased secretion.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death among women in industrialized countries: >50% of postmenopausal women will die of CVD. Estrogens have been hypothesized to protect against atherosclerosis, because the incidence of CVD is quite low before the menopause. Premenopausal women have approximately one-fifth the CVD mortality of men, but after the menopause their mortality exponentially rises to approach that of men.12 One explanation is that the estrogen of a premenopausal woman confers protection, which is lost at menopause; this is supported by the observation that women who undergo a premature surgical menopause (i.e., bilateral oophorectomy) and who do not use postmenopausal estrogens have twice as much CVD as age-matched premenopausal controls. If they use postmenopausal estrogens, however, their incidence of CVD is the same as that of premenopausal women of the same age.13 Premature natural menopause, in contrast, has not been found to increase the risk of CVD when subjects are controlled for age, smoking, and estrogen use.13

Most epidemiologic studies have found that postmenopausal estrogen users have a lower incidence of CVD compared with nonusers. The Nurses’ Health Study,14 the largest cohort study, which followed 121,000 women for as long as 18 years, identified 425 cases of fatal myocardial infarction (MI). The adjusted relative risk of death from coronary heart disease was significantly reduced to 0.47 (95% CI, 0.32–0.69) for current hormone use but unchanged at 0.99 (95% CI, 0.75–1.30) for past use. The greatest decrease was seen in women who had at least one risk factor for heart disease (current tobacco use, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes, parenteral history of premature MI, obesity). Substantially less benefit was seen in women with no risk factors. Concomitant progestin use did not appear to detract from this benefit.

Additional evidence for the benefit of estrogens was provided by a prospective study of more than 8000 postmenopausal women living in a moderately affluent retirement community in southern California.15 After 7 years of observation, >1400 of these women had died. The investigators found that the women who had ever taken postmenopausal estrogens had 20% less all-cause mortality compared with women who did not (relative risk [RR] of death, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.70–0.87). The greatest reductions in mortality were seen with current use and with long durations of use: current use for more than 15 years was associated with a 40% reduction in mortality rates. This reduction in mortality rates was not dependent on the dosage of estrogen used: both high (i.e., ≥1.25 mg daily) and low (i.e., ≤0.625 mg daily) doses of oral conjugated equine estrogens (the most common estrogen used) were associated with nearly equal reductions in mortality. Few women took progestins or parenteral estrogens; therefore, the effect of those hormones on mortality cannot be determined from this study.

Most of the reduced mortality in estrogen users seen in this study15 was the result of fewer deaths from occlusive arteriosclerotic vascular disease. Estrogen users were also found to have 20% less cancer mortality, which was observed for many malignancies, including breast cancer (RR, 0.81). One possible explanation is that estrogen users may have had greater health awareness and/or increased medical surveillance and consequently had less extensive disease at the time of diagnosis. As expected, estrogen users had excess mortality from endometrial cancer (RR, 3.0).

Women who underwent menopause before age 45 years showed the greatest benefit from estrogen use.15 For the group of women whose menopause occurred after age 54 years, estrogen treatment did not reduce mortality rates. Estrogen use also appeared to reduce mortality for women who smoked, who had hypertension, or who had a history of angina or myocardial infarction, approaching that of healthy women who did not use estrogen. This appears to be a very important finding: at one time, hypertension, tobacco use, and coronary disease were thought to be relative contraindications to estrogen replacement. This was based on the increased incidence of stroke and heart attack seen with high-dose oral contraceptives, as well as with high-dose conjugated estrogens prescribed to men as secondary prevention of myocardial infarction.16

Conceivably, the results of this study15 may argue for offering estrogen replacement to nearly all postmenopausal women, particularly those who underwent a relatively early menopause or who have risk factors for CVD. Perhaps the results may further argue for continuous, long-term treatment, because increasing durations of treatment were associated with further reductions in mortality. It should be remembered, however, that this study is an epidemiologic observation of estrogen users and nonusers and is not a clinical trial. Although the investigators controlled for many potential confounding factors, the possibility nevertheless exists that healthier women are more likely to seek and to be prescribed estrogens. Only randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials are free of this bias (see later in this chapter).

Women with preexisting atherosclerosis may benefit from estrogen replacement.17 In one study, estrogen users undergoing coronary catheterization were less likely to have demonstrable disease compared with nonusers (RR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.29–0.67).18 The investigators performed a retrospective analysis of the all-cause mortality of women who have undergone catheterization during the preceding 10 years. Relatively few women in this study were estrogen users, which was defined as estrogen use at the time of catheterization (5% subjects) or beginning some time thereafter (another 5% subjects). The adjusted 10-year survival of women with severe coronary stenosis who used estrogens was 97%, but it was only 60% for nonusers. For mild to moderate coronary stenosis, 10-year survival was 95% for users and 85% for nonusers. For women with normal coronary arteries, the 10-year survival was 98% for users and 91% for nonusers, a difference that was not statistically significant. These findings suggest that women with severe coronary atherosclerosis may substantially benefit from estrogen use. However, this retrospective study may be biased by the fact that the decreased mortality seen in estrogen users may have been, in part, a self-fulfilling prophecy: estrogen nonusers who lived the longest after catheterization had the greatest opportunity to begin estrogen treatment and therefore became “estrogen users.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree