Chapter 36 Pneumocystis Pneumonia

During the first decade of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic, Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) became widely recognized as the most common presenting clinical manifestation of AIDS in North America and Western Europe.1–7 Clinicians became quite adept at monitoring CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts to determine when patients were most likely to develop PCP, and they became familiar with recognizing the initial manifestations, establishing the diagnosis, instituting therapy, and prescribing prophylaxis.8–14

Since the mid-1990s the AIDS epidemic has witnessed dramatic changes in the epidemiology and management of PCP. In patients with access to medical care, PCP has become a much less common disease as a result of early diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease, widespread use of anti-Pneumocystis prophylaxis, and early intervention with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).14–27 PCP continues to be common, however, in those who do not have access to medical care, do not get tested for HIV infection early in the course of their disease, elect not to treat their HIV disease consistently and aggressively, or do not respond optimally to available regimens.22–24,26–28 Thus PCP continues to occur in North America and Western Europe, but incidence differs among patient populations depending on the availability and the quality of their long-term medical management.22–24,26–28 PCP also occurs in patients in developing countries and its incidence appears to be greater than previously reported.29–33

TAXONOMY

Pneumocystis can be found in a wide variety of mammals, including rodents, horses, nonhuman primates, and humans. The organism is difficult to culture. Murine Pneumocystis can be grown with difficulty, achieving only a modest increase in number. Human Pneumocystis has never been cultivated successfully. Antigenic analysis indicates that each species of animal is infected by a distinct form of Pneumocystis.34–36 The environmental reservoir of Pneumocystis is unknown, but humans do not appear to acquire it from other animals. Many humans appear to be infected early in life and can probably be reinfected by different human strains later in life.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

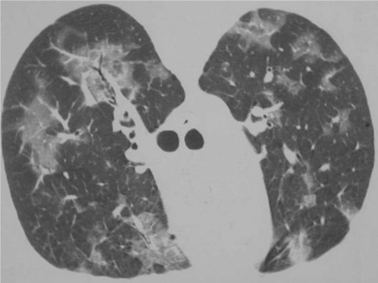

Pneumocystis pneumonia almost always presents as pulmonary dysfunction.9,10,37 Although extrapulmonary or disseminated disease has been repeatedly reported in the literature, these presentations are infrequent regardless of the type of prophylaxis a patient is receiving.38–42 When patients come to medical attention early in the course of their PCP, they typically have minimal symptoms. They often complain of a mild cough that is usually nonproductive, exertional dyspnea, or a substernal “catching”. They may have a normal chest radiograph and normal arterial blood gases with no fever at this juncture, although a high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan might show ground glass opacities (Fig. 36-1), and a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or induced sputum specimen could contain many organisms.9,10,37,43–46 Diagnosis and initiation of therapy at this stage clearly is associated with the best prognosis for avoiding hospitalization, complications, and death.47–57 Patients may also present with more advanced disease, first coming to medical attention when they are on the brink of respiratory failure. Another presentation of which clinicians should be aware is pneumothorax. Finding a pneumothorax in an HIV-infected patient with no other precipitating cause should raise the possibility of PCP.58,59

This disease most often presents with clinical and radiologic features consistent with bilateral pneumonia, manifesting with fever, nonproductive cough, shortness of breath, and the characteristic diffuse interstitial, reticular, or granular pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiography (Fig. 36-2).43–45 Almost every conceivable radiographic pattern has been reported with PCP, including diffuse alveolar infiltrates, lobar infiltrates, nodules, cavities, upper lobe predominance, and asymmetrical patterns.43–46,60,61 Thus clinicians must suspect PCP when pulmonary symptoms occur in any patient with HIV, regardless of radiologic appearance, especially if the patient has a low CD4+ T-lymphocyte count.

Today, patients continue to develop PCP despite the efficacy of prophylactic regimens and antiretroviral agents (Table 36-1).22–24,26–28 One issue that has been apparent since before the era of antiretroviral therapy is that PCP occurs over a fairly wide range of CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts. Although most cases occur at CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts of less than 100 cells/μL, and 85–90% occur at CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts of less than 200 cells/μL, some occur at counts of 200–300 cells/μL and a few at CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts of more than 300 cells/μL.3,8,24,26 A substantial fraction of these patients presenting with PCP at CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts of more than 200 cells/μL have not manifested either unexplained fever or oropharyngeal candidiasis, which are both risk factors for PCP independent of the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count.8 Thus more sensitive laboratory or clinical indicators of disease would be useful. The HIV viral load is an independent predictor of AIDS-defining events,62,63 and might be a logical companion measurement to the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count but how precisely to use this factor to indicate the utility of initiating PCP prophylaxis is currently unclear. A high viral load (e.g., >100 000 copies/mL) in a patient with a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of 200–300 cells/μL would be a logical reason to consider prophylaxis. Clinical markers, including wasting, the occurrence of a previous AIDS-defining event, or the occurrence of a previous episode of pneumonia of any type, also are risk factors for PCP independent of the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count. It may be reasonable to use these indicators to initiate PCP prophylaxis before the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count falls to 200 cells/μL, especially in patients whose HIV viral load is high or whose CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts are declining rapidly. In addition, if another opportunistic infection occurred at an unusually high CD4+ T-lymphocyte count or if a prior episode of PCP occurred at a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of more than 200 cells/μL, it is probably prudent to recommend prophylaxis despite a “high” CD4+ T-lymphocyte count.

Table 36-1 Reasons Patients Develop PCP During the Era of HAART

| Failure to Take Prophylaxis |

| Lack of awareness of HIV infection Lack of access to healthcare Failure of healthcare provider to prescribe prophylaxis Failure of patient to adhere to prophylaxis Development of PCP before recommended indicators occur |

| Breakthrough of Prophylaxis |

| Immunologic failure Less than complete efficacy of prophylactic regimen Drug resistance (?) |

Considerable evidence supports the concept that the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count is an accurate indicator of susceptibility to PCP even in patients receiving HAART or interleukin-2 (IL-2).63–66 The nadir of the CD4+ T-lymphocyte fall prior to the institution of HAART or IL-2 does not influence the predictive value of counts substantially.63

DIAGNOSIS

A definitive diagnosis of PCP depends on recognition of organisms in pulmonary secretions or tissue. Pneumocystis from humans has never been convincingly grown in culture despite extensive efforts using various culture media, cell types, and special conditions. Detection of serum antibodies by highly specific Western blot techniques or other serologic approaches has yielded interesting epidemiologic data but has not yet been shown to be useful for diagnosing acute disease, monitoring the response to therapy, or determining the prognosis.67–73 In one study, the measurement of plasma S-adenosylmethionine concentrations was found to be a sensitive test for PCP.74 S-adenosylmethionine is an important biochemical intermediate in many cellular functions, and it has been shown to be depleted in laboratory animal studies of PCP. In one study, plasma S-adenosylmethionine concentration was undetectable in 14 of 15 HIV-infected patients with either histologically confirmed or clinically suspected PCP.74 In addition, serial S-adenosylmethionine concentrations appeared to parallel the clinical course of PCP treatment in these patients. However, a high sensitivity and specificity of this test for PCP have been difficult for other investigators to confirm.

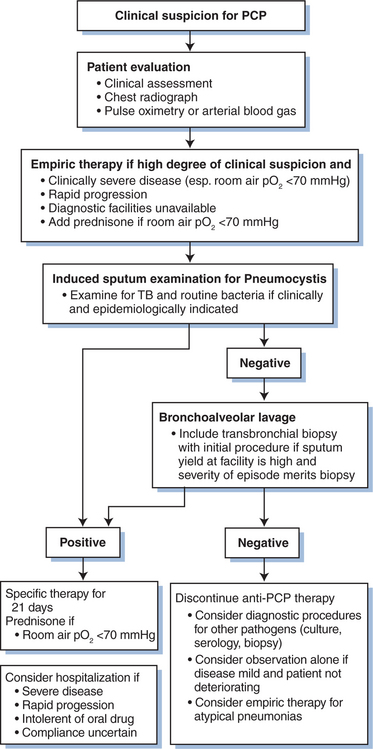

An approach to the diagnosis and management of PCP is outlined in Figure 36-3, and sensitivities of diagnostic procedures for PCP are summarized in Table 36-2. At most medical centers, PCP is diagnosed by detecting organisms in BAL fluid or induced sputum. Prior to the early 1980s, open lung biopsy was conventionally used to diagnose PCP.75,76 When bronchoscopy was introduced, it became clear that bronchial washings and brushings could detect Pneumocystis in 30–70% of cases.11,76 Bronchial washings or brushings do not sample as many alveoli as BAL, however. When BAL is properly performed (i.e., the bronchoscope is wedged in a terminal bronchiole and 10–20 mL aliquots of normal saline are instilled until 30–40 mL has been collected), this technique rarely misses cases of AIDS-associated PCP; the sensitivity of the procedure is 95–99%.12,77 Some laboratories report that PCP may be more difficult to diagnose in aerosolized pentamidine-treated patients.78–81 Some reports suggest that site-specific lavage (i.e., performing lavage in a radiologically affected area of the lung), preferentially lavaging the upper lobes, or performing bilateral lavage may increase the diagnostic yield.82–84 Bilateral lavage or upper lobe lavage is not, however, performed routinely at most centers.

Figure 36-3 Management algorithm for suspected acute Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP). TB, tuberculosis.

Table 36-2 Sensitivity of Procedures to Diagnose PCP by Visualization of the Organism

| Technique | Sensitivity (%) | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Oral or oropharyngeal wash (gargle) | 50–94 | Predominantly a research tool; specificity less than 100% when combined with PCR techniques |

| Expectorated sputum | 10–52 | Rarely used |

| Induced sputum | 55–97 | Many medical centers have >80% sensitivity and 99% specificity |

| Nonbronchoscopic lavage | Variable | At a few centers more readily available than bronchoscopy |

| Bronchoscopy | ||

| Bronchial washings | 30–70 | Rarely used |

| Bronchial brushings | 30–70 | Rarely used |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage | 95–99 | Procedure of choice |

| Transbronchial biopsy | 70–90 | Rarely necessary to diagnose PCP |

Transbronchial biopsy is rarely necessary to diagnose PCP, so it is often not performed as part of an initial diagnostic procedure. If BAL does not reveal PCP or any other likely pathogen, bronchoscopy is often repeated, especially if the patient fails to improve on empiric therapy; and transbronchial biopsy is performed to search for processes other than PCP, such as infection with cytomegalovirus, mycobacteria, or fungi. The diagnostic yield of transbronchial biopsy for any of these processes is subject to sampling artifact because characteristically only a few small pieces of tissue are obtained. The more severe the PCP and the more tissue obtained, the higher is the diagnostic yield. At most centers it is unusual to detect PCP by transbronchial biopsy if BAL has been negative because of the high sensitivity of BAL.77

Open lung biopsy has a high yield of PCP detection if a large piece of tissue from an affected lobe is obtained. However, the diagnostic sensitivity of BAL and transbronchoscopic biopsy for virtually all pathogens makes open lung biopsy rarely necessary. Few medical centers perform more than a few open lung biopsies on AIDS patients per year. Patients with suspected extensive pulmonary Kaposi sarcoma comprise one of the few populations in whom open lung biopsy is likely to be useful, although even here chest CT scans and endobronchial examination usually suffice.85,86

Percutaneous needle aspiration is occasionally useful for obtaining tissue from focal lesions if BAL is nondiagnostic.87,88 Although Pneumocystis occasionally is documented to cause such focal disease, in most circumstances another causative process is identified.

Nonbronchoscopic alveolar lavage has been reported to have a higher diagnostic yield than induced sputum at one center.89–91 This technique does not require an expensive bronchoscope but instead uses a disposable plastic catheter. It has been proposed that nonpulmonologists could use this technique in their offices or clinics. However, the yield of this technique is not as high as BAL in the best of circumstances; at some centers the yield has been considerably lower. Moreover, any catheter passed through the epiglottis has the potential to induce bronchospasm or vomiting and aspiration. Thus operators must be prepared to deal with airway emergencies and to be trained in conscious sedation procedures. For many nonpulmonologists, such potential complications, although rare, make this procedure imprudent for use in settings where full anesthesia or critical care support is not available.

Detection of organisms in sputum specimens offers the advantage of a noninvasive procedure that can be easily scheduled and is less expensive to perform.92 Expectorated sputum has a low yield and is usually not worthwhile. For patients who are intubated, tracheal aspirates also have a low yield. Saline induction of sputum produces samples that provide far superior results compared to expectorated samples. Many institutions report a diagnostic yield from induced sputum ranging from 75% to 95%.77,93–97 Such high sensitivity requires that patients be encouraged to cough up material after nebulization with hypertonic saline and should be performed using a high-flow nebulization delivery device. High sensitivity also requires scrupulous laboratory processing of the specimen, including digestion of mucoid material, centrifugation of cellular material into a pellet, and thorough direct microscopy by an experienced observer using an appropriate stain on the microscopic slide. Many laboratories prefer a direct immunofluorescent stain that permits easy visualization of cysts or trophozoites. However, Giemsa, Diff-Quik, toluidine blue-O, and methenamine silver have been used successfully. The methenamine silver and toluidine blue-O techniques stain only cysts, whereas the Giemsa, Diff-Quik, and immunofluorescent techniques allow detection of both cysts and trophozoites.

There has been considerable interest in using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect Pneumocystis in blood, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, urine, or oral washings.98–113 Several laboratories have reported that PCR can detect Pneumocystis in the serum or urine of a small fraction of patients with PCP, but the sensitivity appears to be low in these specimens.98–100 PCR has been used more successfully to detect Pneumocystis in BAL fluid, sputum, and oral washes. Detection of Pneumocystis in an oral wash would be advantageous for diagnostic or epidemiologic studies, as such a specimen is easier to obtain than induced sputum.105–108110 For these specimens, PCR provides more sensitivity than staining, but false-positive results have diminished the clinical utility of currently available assays. A highly specific PCR assay might be easier to perform than tinctorial methods for some laboratories if they have already established a rigorously organized PCR laboratory for a wide variety of pathogens. However, more work is needed to develop approaches that can distinguish patients who have active pneumonitis due to Pneumocystis from patients who are colonized. Quantitative assays are currently being developed that show promise for effectively distinguishing such patients.110 The use of PCR assays, especially with oral washes, is currently a research procedure and is not available for diagnostic purposes in most laboratories.

Nonspecific tests have been described for inclusion in the diagnostic evaluation of pulmonary dysfunction. Oxygen saturation evaluation during rest and exercise,114 chest HRCT,46 measurement of the diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLco),115 gallium scanning, and serum enzymes such as lactate dehydrogenase116–118 have been studied for their ability to predict the presence of PCP. None of these tests appears to be specific and sensitive enough to warrant diagnostic use in clinical settings without subsequent microscopic confirmation.

THERAPY

Initial Therapy

Because the best indicator of prognosis is the alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient at the time specific therapy is initiated,47–52,55,56 it is logical to make prompt initiation of appropriate therapy a high priority. This obviously requires that patients be advised to come to their healthcare provider when they have any suggestive symptoms, even if such symptoms are mild, and that healthcare providers expeditiously initiate management by obtaining diagnostic tests, starting empiric therapy, or both.

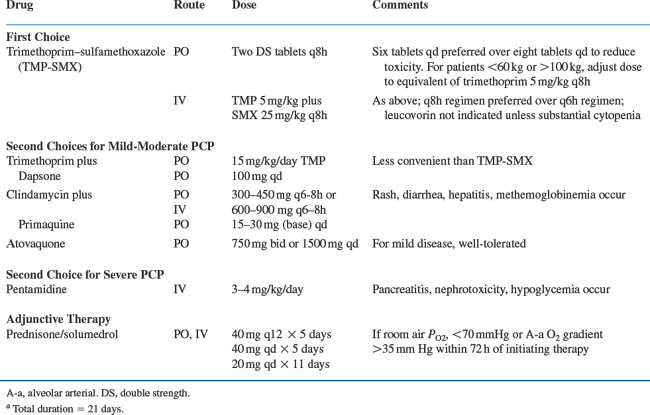

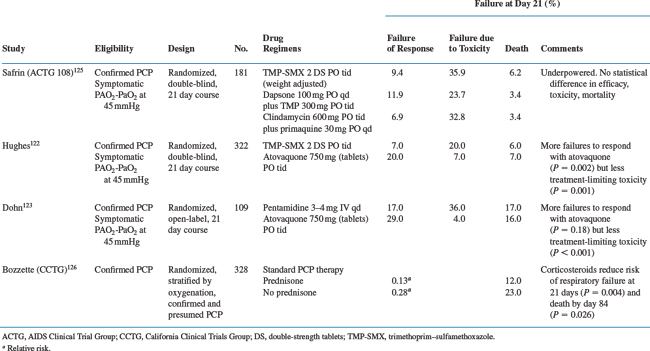

Therapeutic regimens119–127 for acute PCP are listed in Tables 36-3 and 36-4. In some situations, empirical therapy without confirming the diagnosis may be appropriate: patients with room air PO2 above 80 mmHg, patients who are clinically stable, and patients who do not have prompt access to diagnostic facilities are reasonable candidates for empirical therapy.128–130 Therapy can be administered orally if there is no evidence of gastrointestinal dysfunction and the patient adheres to the regimen. If therapy is empirical, a macrolide (e.g., azithromycin) or fluoroquinolone (e.g., levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) is often added to treat other processes that are likely to present with manifestations similar to PCP.

Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole is always the drug of choice unless the patient has a history of life-threatening intolerance.119–127 In every study performed to date, including HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole has been as effective as alternative drugs or more effective. Specifically, there are few patients who have a poorer clinical response to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole than to other drugs, except perhaps intravenous pentamidine, which has equivalent efficacy to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazolebut is more toxic.119–121 Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole is well-absorbed and can be given by mouth to compliant patients who have no major gastrointestinal dysfunction and who have only mild disease. A dose of two double-strength (DS) tablets (each DS tablet contains 160 mg trimethoprim and 800 mg sulfamethoxazole) or intravenous trimethoprim 5 mg/kg with sulfamethoxazole 25 mg/kg is preferred every 8 h rather than every 6 h to reduce toxicity. There is no need to give concurrent leucovorin (there may be some reduction in efficacy, although this point is controversial and not conclusively established) unless cytopenias occur that appear to be drug-related.131 Patients may be managed on oral therapy as outpatients if they have mild disease (room air PO2 above 80 mmHg), their clinical disease is not progressing rapidly, they are reliable, and they have no major gastrointestinal dysfunction.

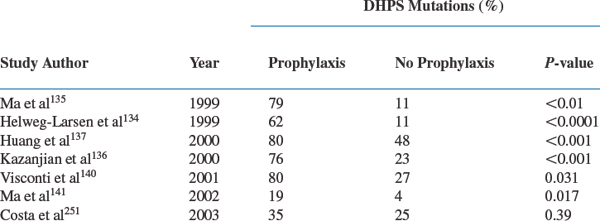

There is evidence that Pneumocystis can develop resistance to sulfamethoxazole, the more active component of the trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole combination.132–147 This resistance has been suggested by sequencing the target enzyme for sulfamethoxazole, dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS), and observing nonsynonymous point mutations that have been associated with sulfa drug resistance in other microorganisms. DHPS mutations are found especially in patients who have been exposed to sulfonamides or sulfones in the past (Table 36-5). Whether the reported mutations are of a magnitude to be clinically important remains to be determined. Current reports are contradictory.134,136,139,144,146–148 Helweg-Larsen et al reported that DHPS mutations were an independent predictor of mortality in a retrospective analysis of a Danish cohort.134 Some subsequent studies have found that DHPS mutations were associated with an increase in morbidity but none has found an association with increased mortality.136,139,147

Toxicities of trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole and other drugs are listed in Chapter 79.13,119,120,122,124,125,149–152 A complete blood count, electrolytes, liver function tests, and creatinine should be monitored two or three times weekly to assess toxicity, as should symptoms and signs. Repeat chest radiographs and arterial blood gases are not necessary unless the patient is deteriorating or is clinically tenuous (i.e., the initial PO2 on room air was less than 70–80 mmHg). A chest radiograph at the end of the therapeutic course is useful for future comparison.153 Monitoring sulfonamide levels is unnecessary except in unusual patients with unstable renal function or patients receiving renal replacement therapy.152 A 21-day course is standard, although there is no compelling evidence that 21 days of therapy is more effective than 14 days. Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole pharmacokinetics are not influenced significantly by other drugs, although the dose should be adjusted if there is significant renal dysfunction.

The efficacy of trimethoprim plus dapsone for mild-to-moderate PCP is comparable to that of trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, and the former may be somewhat better tolerated than the latter.125,154 This regimen is less convenient than trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole because the dapsone must be taken once per day and the trimethoprim three times daily. Occasionally patients develop clinically important methemoglobinemia while on dapsone or hemolyze as a result of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. It is rarely necessary to screen for G6PD deficiency prior to initiating therapy unless there is a strong suspicion of deficiency, as might be the case for patients of Mediterranean ancestry and patients from the subtropical zones of the Eastern Hemisphere. It is not clear how many patients who are truly intolerant of trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole can tolerate this regimen. A history of life-threatening trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole adverse reactions should preclude the use of dapsone plus trimethoprim. For patients who do not tolerate trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole owing to nonlife-threatening complications, dapsone–trimethoprim is a reasonable option.

Intravenous pentamidine appears to have efficacy equivalent to that of trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole.13,119,121,155–157 When given in a daily dose of 4 mg/kg or perhaps 3 mg/kg (the latter is less well studied),155 the response to therapy is excellent. However, nephrotoxicity,158 dysglycemia,159 pancreatitis, and cardiac arrhythmias160 (torsade de pointes; see Chapter 68) make this drug complicated to administer. A baseline electrocardiogram to assess the QT interval (see Chapter 68) is useful but not mandatory. If the QT interval is more than 0.48 s and cannot be corrected by normalizing electrolytes or if other drugs that substantially prolong the QT interval are used concurrently (e.g., amiodarone, sotalol, perhaps certain quinolones), a cardiologist might be consulted before administering the drug. The use of monitoring to follow QT intervals and rhythm is controversial. Patients may become hypoglycemic during therapy or even during the several weeks after therapy. This hypoglycemia may be profound and symptomatic; and it can rarely result in death.158,159 Following acute therapy, the effects of pentamidine on the pancreas may lead to decreased insulin production and hyperglycemia, requiring chronic insulin therapy. Renal dysfunction may manifest as azotemia or tubular dysfunction. Renal dysfunction appears to be a risk factor for dysglycemia. The pancreatitis associated with pentamidine can be severe. There is some evidence that patients who have been given didanosine or zalcitabine (and perhaps stavudine) may be predisposed to pentamidine-induced pancreatitis, but this remains to be confirmed.

Aerosolized pentamidine has been used for therapy of acute PCP.155–157 Although it is somewhat effective, especially for patients with mild disease, the relatively low response rate and high relapse rate makes it a poor option for therapy. It should almost never be used for therapy of acute disease.

Atovaquone has few life-threatening toxicities and a high degree of efficacy.161,122,123 It is not, however, as potent as trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole or intravenous pentamidine. In addition, steady-state levels are not reached for several days, absorption can be unpredictable, and some patients find the current liquid formulation to be unpleasant. Atovaquone absorption is improved by ingestion with a high-fat meal. Thus atovaquone has a therapeutic role for patients with mild, stable disease who have no evidence of gastrointestinal dysfunction. For this population, if neither trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole nor trimethoprim–dapsone is tolerable, atovaquone is a good option. An intravenous preparation is not commercially available. Mutations in cytochrome b, the target for atovaquone, have been described.162 Their clinical importance is unknown.

Clindamycin plus primaquine is an effective regimen that appeared comparable to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole and dapsone–trimethoprim in large but underpowered studies.125,163,164 Clindamycin can be given orally or parenterally; primaquine is available only as an oral preparation. The regimen is inconvenient in that two drugs are involved. In addition, clindamycin causes a substantial amount of rash, diarrhea, and hepatic dysfunction in this population, and primaquine can be associated with G6PD deficiency-related hemolysis. This regimen is a reasonable alternative for patients with mild disease who can absorb an oral regimen and who cannot tolerate trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole.125,163,164

Prednisone is part of standard therapy for patients whose initial room air PO2 is less than 70 mmHg or whose alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient is greater than 35 mmHg.126,165–168 Studies show that mortality is reduced substantially in HIV-infected patients with an initial room air PO2 below 70 mmHg when prednisone is added to specific chemotherapy within 72 h of initial therapy. Symptomatically and in terms of oxygenation, PCP also disappears faster with prednisone than without. Whether there is an important survival benefit when prednisone is added to specific therapy for patients with initial PO2 values higher than 70 mmHg is unclear because the mortality in this population is low even without prednisone therapy.

There has been considerable concern about the safety of prednisone. There is, however, no convincing evidence that a 21-day course using the regimen in Table 36-3 increases the likelihood that another opportunistic infection, Kaposi sarcoma, or tuberculosis will appear or, if present, will be exacerbated. Metabolic abnormalities induced by prednisone are usually readily managed.

Acute PCP can be complicated by electrolyte abnormalities (especially syndromes of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone) or pneumothorax.169 These complications can be managed using standard principles.

Should antiretroviral therapy be initiated or continued when patients have acute PCP? There is little information to indicate whether initiating HAART in the face of acute PCP can improve outcome.57 It is conceivable that such therapy could improve immune function. It is also conceivable that HAART could exacerbate pulmonary dysfunction by causing a more intense inflammatory response (i.e., immune reconstitution syndrome).170,171 In general, it is probably preferable not to initiate HAART during an episode of PCP; absorption of drugs and adherence may be erratic and could thus lead to rapid development of retroviral resistance to the HAART regimen. In addition, if multiple drugs (trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole plus HAART) are started simultaneously it may be difficult to know to what to attribute toxicity. For patients who have been receiving HAART it may be preferable to suspend HAART therapy until the patient is stable. On the other hand, patients who are critically ill with PCP and accompanying respiratory failure are a subset of PCP patients with a high mortality.54,57,172 One study reported that HAART started either before or during hospitalization was an independent predictor that was associated with a lower mortality (odds ratio (OR), 0.14; 95% confidence interval (95% CI), 0.02–0.84; P = 0.03).57 While the challenges of administering HAART to patients are magnified in the ICU, the subset of PCP patients who are worsening despite PCP treatment and optimal ICU care, are individuals where consideration of HAART is warranted.

Salvage Therapy

A frequent issue is how to manage patients who are not improving on their initial regimen (Table 36-6). Clinicians must understand that the median time to clinical or physiologic improvement is 4–8 days, and that the natural history of PCP is to get worse during the initial 72 h following institution of therapy unless prednisone is part of the regimen.9,166 Thus a change in therapy before a 4- to 8-day course of therapy is premature; it is preferable to wait 6–8 days before changing agents rather than changing earlier. If a patient is deteriorating and the PO2 on room air approaches or falls below 70 mmHg at any point, prednisone should be added to the regimen.173

Table 36-6 Approach to Patients Failing PCP Therapy

| Days 4–6 |

| Days 6–8 |

There have been no trials to determine the best time to switch therapy, the most effective salvage regimen, or if combination therapy (e.g., trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole with intravenous pentamidine) is preferable to a single-drug regimen.174 Many clinicians carefully assess the patient for concurrent pulmonary processes (i.e., bronchoscopy should be repeated after 4 days of therapy looking for pathogens other than Pneumocystis, and the patient should be carefully assessed for concurrent noninfectious processes such as heart failure, bronchospasm, or pulmonary emboli); if there is no response after 6–8 days of therapy, they switch from trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole to intravenous pentamidine (some clinicians add subsequent drugs in preference to switching). Some clinicians prefer not to use pentamidine in patients who have been heavily exposed to didanosine or stavudine. If a patient is deteriorating or failing to improve prior to days 6–8 on a regimen other than trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, strong consideration should be given to using this regimen, even if desensitization is required in intensive care unit.

In terms of alternatives to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole or intravenous pentamidine, a clindamycin with primaquine combination has been used successfully to salvage some patients failing their initial therapy.163 Because primaquine is available only as an oral agent, and because clindamycin alone is ineffective in animal models, many clinicians are reluctant to use clindamycin–primaquine as a salvage regimen if other options are available. Some clinicians have used aerosolized pentamidine in addition to intravenous therapy, but there are no data to indicate if this is useful or safe.

Mechanical ventilation is an appropriate option for many patients with PCP.175–177 Patients who had a good quality of life prior to the onset of PCP and who have not received at least 6–8 days of therapy, have not received corticosteroids, or have reversible processes such as congestive heart failure or pneumothorax are reasonable candidates for mechanical ventilation if they are willing to try this mode of support and if their functional status was reasonable prior to PCP. The goals of mechanical ventilation and a realistic assessment of the prognosis must be carefully reevaluated daily. A summary of an approach to a patient who appears to be failing therapy is presented in Table 36-6.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree