Physical Examination of the Thyroid Gland

James V. Hennessey

Traditionally, clinicians have correlated characteristic physical findings with historical clues to synthesize a diagnosis. Advancements in diagnostic techniques seem to have relegated physical examination of the thyroid to a less important role leading some to conclude that examination of the thyroid may be a lost or unlearned art for many physicians (1,2). Topical reviews and consensus guidelines, however, continue to emphasize the importance of thyroid physical findings detected during clinical assessment (1,3,4,5,6). Techniques of examination and the physical findings described are taught as expert opinion and in some cases as a consensus of broad agreement.

Evaluation of the patient with potential thyroid disease begins with the interview. Hoarseness of the patient’s voice may be a sign of recurrent laryngeal nerve compression, associated with large benign goiters (7) or malignant thyroid lesions, and necessitate laryngoscope confirmation (8). Significant thyroidal displacement of the trachea may cause an inspiratory stridor requiring emergent intervention. Compromise of vocal, swallowing, and upper airway function may result in characteristic complaints from the patient obtained in a thorough review of systems. Some refer to the “three Ds” (dysphonia, dysphagia, and dyspnea) discovered in the interview and use the presence of these symptoms when estimating the likelihood of serious abnormalities of thyroid anatomy (9).

Inspection of the neck begins with a survey to assess for scars, asymmetry, or masses. The survey is likely best accomplished from a vantage point in front and off to the side of the patient (7,8). A scar indicating past thyroid surgery points to potential thyroid disease in patients with nonspecific symptoms (8,10,11). Erythema overlying a tender swelling is seen in acute suppurative thyroiditis (7), infected thyroglossal duct (12), and brachial cleft cysts (13).

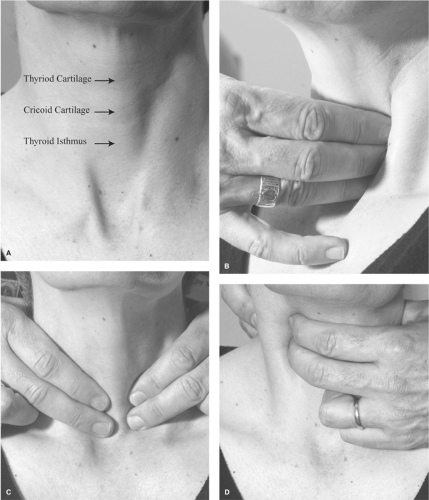

The patient extends the neck to lift the thyroid and stretch the overlying skin. The head is tilted back by a moderate degree to relax the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscles (8,14). The examiner identifies the thyroid and cricoid cartilages (Fig 15.1A). Light from the side and slightly above enhances a shadowed border of these features at rest and during swallowing. Normally, the extended neck from the cricoid to the sternal notch will form a straight line. Viewed from the side, anterior bowing suggests the presence of a goiter (15,16,17).

Facing the patient, the trachea is inspected for deviation from midline. As the thyroid is fixed to the pretracheal fascia, the gland will rise with the trachea upon swallowing (2,8). The patient should sit comfortably with a cup of water (18). During the normal swallowing act, both the thyroid and the trachea move upward some 1.5 to 3.5 cm and hesitate momentarily before returning to their resting position (19). A neck mass

is likely not thyroidal if it does not move upon swallowing, does not hesitate along with the thyroid and trachea before returning to its original position, or is noted to move in an asynchronous manner in relation to the thyroid and trachea (15). Thyroid movement upon swallowing may be lost if a goiter is so large that it occupies extensive space in the neck, or if an invasive carcinoma, lymphoma, or Riedel’s thyroiditis has caused fixation to the surrounding tissues (8,20,21).

is likely not thyroidal if it does not move upon swallowing, does not hesitate along with the thyroid and trachea before returning to its original position, or is noted to move in an asynchronous manner in relation to the thyroid and trachea (15). Thyroid movement upon swallowing may be lost if a goiter is so large that it occupies extensive space in the neck, or if an invasive carcinoma, lymphoma, or Riedel’s thyroiditis has caused fixation to the surrounding tissues (8,20,21).

Pseudogoiter refers to apparent thyroidal enlargement when no true goiter is present. Thin patients may appear to have a prominent appearing thyroid, especially when the gland is located higher in the neck, overlying the thyroid cartilage. These glands are actually normal in size by palpation (22). The presence of other cervical masses such as adipose tissue, either diffusely distributed or as a lipoma (23), cervical lymphadenopathy, brachial cleft cysts, or pharyngeal diverticula (15) may simulate the appearance of a goiter. Finally, the illusion of a goiter may be seen when patients with long curved necks have exaggerated cervical spine lordosis (Modigliani syndrome), named after the painter whose subjects demonstrated similar neck anatomy (24).

A visible midline mass superior to the isthmus may represent a thyroglossal duct cyst which may present at any age as a tense, nontender round mass at or just below the level of the hyoid bone and accounts for three quarters of congenital neck masses (25). These structures may also present as a lateral nodule, indistinguishable from a lesion of the thyroid (26), may rarely harbor a papillary thyroid cancer (25,27), can undergo acute hemorrhage, or become infected and tender. Despite their cystic nature, these cysts usually do not transilluminate (15). Unique to the typical thyroglossal dust cyst is movement upward as the tongue is extended. Cystic structures located laterally, near the anterior border of the SCM muscles at the level of the hyoid bone (junction of upper one-third and lower two-thirds of the SCM), more likely represent brachial cleft cysts and account for one-quarter of the congenital neck masses (13). Brachial cleft cysts are usually unilateral, slow growing, often fluctuant masses which occur during the second and third decades of life and remain motionless during swallowing. Occasionally, these cysts may become abscessed and eventually rupture (13).

Occlusion of the thoracic outlet by a large retrosternal goiter may occur when the arms are extended over the head. The “Pemberton’s sign” results in the obstruction of venous return from the head and neck region, in visible venous distension over the neck, and plethoric changes in the color of the facial skin and may be associated with difficulty breathing and/or rarely syncope (8,11,28).

There is no consensus as to the optimal position of the examiner to the patient when palpating the thyroid (2,8,11,29). Most agree that with practice and patience the normal thyroid gland can be readily palpated, and the ability to feel thyroid tissue does not automatically signify enlargement of the thyroid (2,4,8,14). The patient may be seated with the head tilted slightly posteriorly but avoiding extreme stretching to relieve tension on the overlying tissues. Bed-bound patients may be examined by the positioning of a pillow across the scapulae, allowing a backward head tilt and easier palpation of the thyroid in the supine position (2).

The author of this section in a previous edition favored thyroid palpation while facing the patient (2). The examiner identifies the cricoid cartilage and seeks the isthmus of the thyroid directly below this landmark (Fig. 15.1A). The presence of kyphosis and emphysema in the elderly may result in the cricoid being displaced behind the sternum making thyroid palpation in such individuals extremely difficult (2). Palpation of the isthmus with the thumb is accomplished by moving the thumb over the isthmus and with the thumb stationary during swallowing. The examiner approaches the patient from the right to examine the left lobe and from the left to examine the right lobe. From the right, the left lobe is palpated with two or three fingers of the right hand lateral to the trachea and medial to the SCM muscles, the thumb placed to the right of the trachea (2) (Fig. 15.1B). Palpation starts above the expected location of the thyroid and moves downward in a circular, rubbing motion, applying gentle (but adequate) pressure as the lobe is examined. The fingers are kept stationary at various levels of interest, and the patient swallows sliding the thyroid beneath the fingers. An alternative to examining from alternate sides of the patient is as follows: From the right by using the right thumb to palpate the right lobe and the fingers to examine the left lobe as described above.

Others recommend palpation with the examiner positioned behind the seated or standing patient (7,10,14,18,30). The examiner places the fingers of both hands on the patient’s neck with the index fingers initially localizing the cricoid cartilage, then moving just below to palpate the isthmus. The head is tilted posteriorly enough to relieve tension of the overlying structures and allow the SCM muscles to displace somewhat laterally. With the tips of two or three fingers overlying the thyroid lobes (Fig. 15.1C), the examiner may slide their fingers over the thyroid, applying sufficient pressure to feel beneath the overlying structures and outlining the borders of both lobes (18). With the finger tips then stationary over the thyroid (Fig. 15.1C), the patient swallows, moving the thyroid under the examiner’s fingers.

If nodules are appreciated, the upper and lower borders may be trapped between two examining fingers so as to allow a rough determination of size in the caudocranial as well as lateral–medial dimension. A simple pocket ruler is used by many clinicians in this initial measurement; alternatively, marking overlying skin and measuring or outlining the nodule on tape covering the nodule and then measuring once the tape is flattened in the patient’s record.

The normal isthmus has a felt-like consistency and is several millimeters in thickness (2). It should be noted that some series have documented the absence of a thyroid isthmus in 16% to 33% of autopsy specimens (31,32). Extending from the isthmus upward and either left or right of midline, a pyramidal lobe may be palpable. A pyramidal lobe, a vestige of the embryonic thyroglossal duct, is present in up to 80% of thyroids examined at surgery (33) and 38% to 58% of recent autopsy series (31,32). A pyramidal lobe may be palpated in the presence of generalized thyroid enlargement as seen in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis or Graves’ disease (33) and may be mistaken for a isthmus nodule or a pre-tracheal, “delphian” lymph node (8,34). Additionally, the presence of a muscle designated as the levator glandulae thyroideae, running from the hyoid to the thyroid cartilage and thyroid isthmus, may, when abnormally enlarged, simulate the presence of a pyramidal lobe (32).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree