PHEOCHROMOCYTOMA

The most important disease of the adrenal medulla is pheochro-mocytoma.1,2,3,4,5,6 and 7 Eighty-five percent to 90% of these tumors occur in the adrenal glands. They arise from cells of neural crest origin and can also be found in some extraadrenal locations (i.e., carotid body, aortic chemoreceptors, sympathetic ganglia, organ of Zuckerkandl). These extraadrenal tumors have been called paragangliomas, chemodectomas, and the like, depending on their anatomic location. Any tumor that makes, stores, and secretes catecholamines and produces symptoms of excessive catecholamine release should be considered a pheochromocytoma and treated as such, regardless of its location.

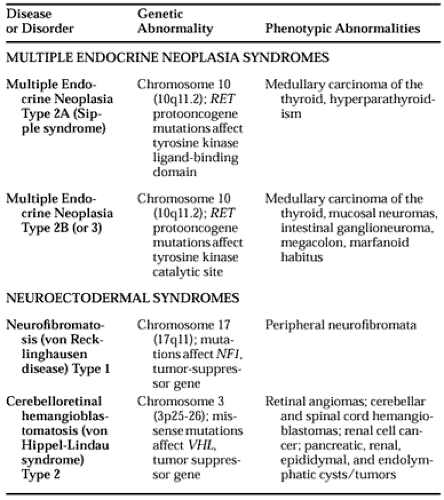

Pheochromocytomas are rare except in certain familial settings. They occur equally in both sexes and at any age, although they are most frequent between the ages of 30 and 50 years. They occur in all races, but less frequently in blacks. When they occur sporadically, 10% are bilateral. When they occur in families, ˜50% are bilateral and they are usually intraadrenal. Pheochromocytomas may occur as a solitary entity or they may be familial, associated with other diseases, such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A or type 2B, von Hippel-Lindau disease type 2, or neurofibromatosis type 1. In most familial disorders inheritance is autosomal dominant8 (Table 86-1) (see Chap. 188). In one study, 23% of unselected patients with pheochromocytoma were found to be carriers of familial disorders—19% had von Hippel-Lindau disease and 4% had multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2.9 In addition, 38% of carriers of von Hippel-Lindau disease and 24% of carriers of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 had pheochromocytoma as the only manifestation of their syndrome. Thus, all patients in families with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 or von Hippel-Lindau disease should be genetically screened to determine if they are carriers and require screening for specific phenotypic traits.9a Patients who are hypertensive or are scheduled to undergo surgery for another aspect of the disease should be screened for pheochromocytoma, even if they are asymptomatic. Although pheochromocytoma is not a normal part of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, it has been associated with pancreatic islet cell tumors in some families.10 In all situations in which several different tumors have been discovered contemporaneously, the pheochromocytoma should be removed before any other surgery is performed. An adrenal gland should be removed only if it contains tumor. A normal-appearing adrenal gland should be left intact and carefully monitored. A pheochromocytoma may not develop in the remaining gland; in one study it appeared in 52% of patients after a mean of 11.87 years.11

Although ˜5% of patients with pheochromocytoma have neurofibromatosis, only 1% of patients with neurofibromatosis have pheochromocytoma.1 In children, 50% of pheochromocytomas are solitary and intraadrenal, 25% involve the adrenals bilaterally, and 25% are extraadrenal (see Chap. 87).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The hallmark of a pheochromocytoma is hypertension, either paroxysmal or sustained (both forms occur with equal frequency). Usually, the hypertension is labile. A typical paroxysm is characterized by a sudden major increase in blood pressure, a severe, throbbing headache, profuse sweating over most of the body (especially the trunk), palpitations with or without tachycardia, anxiety, a sense of doom, skin pallor, nausea with or without emesis, and abdominal pain.1,2 A study of 2585 hypertensive patients, including 11 with pheochromocytoma, noted that headache, sweating, and palpitations were reported by 71%, 65%, and 65%, respectively, of patients with pheochromocytoma.12 When these three manifestations were present and associated with hypertension, they indicated the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma with a specificity of 93.8% and a sensitivity of 90.9%. In the absence of hypertension and this triad of symptoms, the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma could be excluded with a certainty of 99.9%. The hypertensive episode may appear to occur spontaneously, or it may follow acute physical (but not psychological) stress, an increase in abdominal pressure (induced, for example, by palpation of the tumor or defecation), a hypotensive episode, or any activation of the sympathetic nervous system. Hypertensive episodes are usually not caused by anxiety or psychological stress. They may last a few minutes to several hours, and they leave the patient feeling exhausted. These hypertensive episodes may occur in patients who are otherwise normotensive, or they may affect patients with sustained hypertension. Hypertensive episodes may be precipitated by drugs that lower blood pressure acutely (i.e., saralasin13), as well as by opiates, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), dopamine antagonists (i.e., metoclopramide14 and droperidol), radiographic contrast media, indirectacting amines (such as tyramine and amphetamine, which act by displacing the normal neurotransmitter), proprietary cold preparations, and drugs that block neuronal catecholamine reuptake (i.e., tricyclic antidepressants and cocaine). Other symptoms include dizziness and constipation. The patient may experience postural hypotension, hyperglycemia, hypermetabolism, weight loss, and even psychic changes. The hyperglycemia is generally mild, occurs with the hypertensive attacks, and usually does not require treatment. A few patients may say that they feel

“flushed,” but observation of an actual flush should bring into question the diagnosis of a pheochromocytoma.3 The hypertensive crisis associated with pheochromocytoma may precipitate a myocardial infarction, even in the absence of coronary artery disease, or a cerebral hemorrhage. A prolonged excess of catecholamines may produce a cardiomyopathy that is manifested by congestive heart failure. Unexplained shock may also be the presenting feature of pheochromocytoma.15

“flushed,” but observation of an actual flush should bring into question the diagnosis of a pheochromocytoma.3 The hypertensive crisis associated with pheochromocytoma may precipitate a myocardial infarction, even in the absence of coronary artery disease, or a cerebral hemorrhage. A prolonged excess of catecholamines may produce a cardiomyopathy that is manifested by congestive heart failure. Unexplained shock may also be the presenting feature of pheochromocytoma.15

A pheochromocytoma with all the classic signs and symptoms is easy to diagnose. However, the tumor may present with only part of the syndrome. Early in the course of a pheochro-mocytoma, symptoms may be very mild and infrequent, becoming progressively more severe and more frequent later. A patient may have symptoms for years before the diagnosis is made.

The extensive differential diagnosis of a pheochromocytoma includes anxiety and panic attacks, thyrotoxicosis, abrupt withdrawal of clonidine therapy, amphetamine use, cocaine use, ingestion of tyramine-containing foods or proprietary cold preparations (e.g., phenylephrine, pseudoephedrine, phenylpropanolamine) while taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors, hypoglycemia, insulin reaction, angina pectoris or myocardial infarction, brain tumor, subarachnoid hemorrhage, cardiovascular deconditioning, menopausal syndrome, neuroblastoma (in children), and toxemia of pregnancy, among others. A pseudopheochromocytoma has been reported in a patient with parkinsonism treated with selegiline, a monoamine oxidase type B inhibitor, and fluoxetine, an antidepressant that inhibits serotonin uptake.16 Clozapine, a tricyclic dibenzodiazepine, has been reported to mimic pheochromocytoma with hypertension and increased urinary catecholamine levels, both of which revert to normal when the drug is stopped.17 To make these diagnostic distinctions, the physician must obtain a detailed history and, if possible, observe and monitor a hypertensive episode. If this is done, the self-administration of various drugs, the abrupt withdrawal of clonidine (which causes a rebound in central sympathetic outflow resulting in the release of large amounts of epinephrine and norepinephrine), and other episodic disorders are evident. Two of the most difficult differential diagnoses are panic attacks and cardiovascular deconditioning, the latter of which indicates that a patient has been so sedentary that minimal physical activity causes marked tachycardia and sympathetic nervous system activity. These conditions present diagnostic difficulties because neither is characterized by specific symptoms, physical findings, or diagnostic tests. Thus, a pheochromocytoma must be excluded before either of these diagnoses may be established. Pheochro-mocytoma should be suspected in patients with hypertension that is refractory to therapy and in those who have a history of hypertensive episodes occurring during previous general anesthesia or abdominal surgery.

Pheochromocytomas may produce calcitonin, opioid peptides, somatostatin, ACTH, and vasoactive intestinal peptide.4 The high serum calcitonin level may mistakenly suggest a medullary carcinoma of the thyroid until the pheochromocytoma is removed.18 In some patients with pheochromocytoma, the ACTH production has been known to cause Cushing syndrome,19 and production of vasoactive intestinal peptide has resulted in watery diarrhea.6 Pheochromocytomas also produce and secrete into the blood neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin A (CGA), neuropeptide Y, and adrenomedullin.

DIAGNOSIS

URINE TESTS

The diagnosis of a pheochromocytoma must rest on biochemical determinations (i.e., the demonstration of elevated levels of catecholamines or their metabolites in blood or in urine). The traditional and easiest method is the measurement of epinephrine and norepinephrine, of metanephrines (methoxycatecholamines), or of vanillylmandelic acid in a 24-hour collection of urine (Table 86-2).1,2,3 and 4 The urine must be collected in strong acid (i.e., 20 mL of 6N HCl or 25 mL of 50% acetic acid) in an easily sealed, leakproof container; it need not be refrigerated. The measurement of metanephrines in a single random urine sample, or of norepinephrine in a single overnight sample of urine, has been used successfully to diagnose pheochromocytoma.20,21 However, such random specimens show greater variability and, therefore, have less diagnostic sensitivity than do 24-hour samples. Creatinine should be measured in all collections of urine to ensure adequacy of the collection and to serve as a denominator for timed or random samples. Simultaneous analysis of norepinephrine and its metabolite dihydroxyphenolglycol may improve specificity.22 The amount of urinary total metanephrines and vanillylmandelic acid, when expressed in relation to creatinine, decreases with age in normal children.23 Although an amine-free or “vanillylmandelic acid” diet is useful in metabolic studies, it is usually unnecessary in the diagnosis of a pheochromocytoma now that more specific analyses are used. The patient should cease taking all medications, if possible (see Table 86-2). If antihypertensive therapy must be continued, diuretics, vasodilators (hydralazine or minoxidil), calcium channel blockers, and angiotensin-converti ng enzyme inhibitors cause minimal interference. Although any one of the three urinary tests usually indicates the diagnosis, the determination of norepinephrine and epinephrine, or of normetanephrine and metanephrine, is preferred.24,25 Specific assays for urinary epinephrine and norepinephrine are preferable to measurement of total catecholamines, because increased epinephrine may be the

only abnormal finding in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia.26 A markedly elevated value for total catecholamines (i.e., 2000 μg per 24 hours) with normal values for metanephrines and vanillylmandelic acid suggests that the patient is taking methyldopa (metabolized to α-methylnorepinephrine and determined as a catecholamine) and does not have a pheochro-mocytoma. In most patients with a pheochromocytoma, the urine test results are abnormally elevated at all times. For the few patients with only infrequent episodes of hypertension, urine is best collected when the patient is hypertensive. This is accomplished most easily by giving the patient 5 mL of 6N HCl in a 1-L container with instructions to be followed when hypertensive symptoms occur. When symptoms are noted, the patient should void, discard the urine, and note the time. Then, 2 to 3 hours later, the patient should void again, now saving the urine in the container and again noting the time. This urine specimen should be assayed for epinephrine, norepinephrine, and creatinine. A greater than twofold increase in either cate-cholamine over levels obtained from testing a similar control collection is diagnostic.

only abnormal finding in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia.26 A markedly elevated value for total catecholamines (i.e., 2000 μg per 24 hours) with normal values for metanephrines and vanillylmandelic acid suggests that the patient is taking methyldopa (metabolized to α-methylnorepinephrine and determined as a catecholamine) and does not have a pheochro-mocytoma. In most patients with a pheochromocytoma, the urine test results are abnormally elevated at all times. For the few patients with only infrequent episodes of hypertension, urine is best collected when the patient is hypertensive. This is accomplished most easily by giving the patient 5 mL of 6N HCl in a 1-L container with instructions to be followed when hypertensive symptoms occur. When symptoms are noted, the patient should void, discard the urine, and note the time. Then, 2 to 3 hours later, the patient should void again, now saving the urine in the container and again noting the time. This urine specimen should be assayed for epinephrine, norepinephrine, and creatinine. A greater than twofold increase in either cate-cholamine over levels obtained from testing a similar control collection is diagnostic.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree