Personalised management

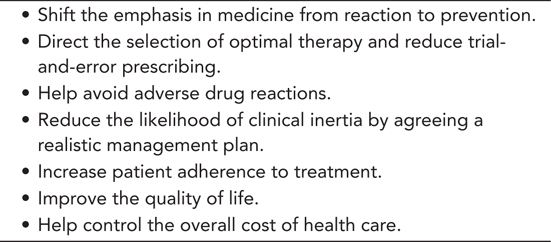

Optimal management of individuals with type 2 diabetes involves complex decision-making to achieve and maintain control of blood glucose as well as other risk factors. The blueprint for care is generally considered the clinical practice guideline, which was developed to reduce inappropriate variations in practice and to promote the delivery of high-quality, evidence-based health care. The highest quality of evidence is generally considered to come from the randomised, controlled clinical trial. However, these are performed with the primary goal of understanding the efficacy of a therapy in a selected group of patients, which may perform differently in varying clinical settings and in broader patient populations than those studied in traditional randomised, controlled trials. The practice of evidence-based medicine should therefore integrate clinical information obtained from a patient with the best evidence available from clinical research and experience. The result is personalised management, a flexible, individual approach that considers important variables involved in a person’s diabetes care. Strategies tailored to the particular characteristics of individual patients have a number of advantages (Table 6.1) and promise to maximally improve the health of the population by optimising outcomes for each individual. This approach is highlighted in both the updated National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance (NICE, 2015) and the 2015 joint position statement from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) (Inzucchi et al., 2015).

FACTORS TO CONSIDER IN PERSONALISED DIABETES MANAGEMENT

When evaluating patients with type 2 diabetes and their individual characteristics and needs, there is no shortage of things to consider. What are the patient’s age, weight and height? How long has he or she been living with the disease? What other medications have been tried and at what doses? How is the patient’s kidney, liver and gastrointestinal function? What is their current haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and fasting glucose level? Does the patient have a history of good adherence to treatment? What about his or her motivation, education level, cultural and social history, literacy level, allergies and tolerance to medications?

After evaluating the patient, the question then becomes which one or combination of more than 13 classes of drugs is most appropriate? Do dosing changes need to be made based on the patient’s kidney or liver function? Are there potential drug interactions with medications the patient is already taking? Does the patient know how to take, where to store and how to evaluate the effectiveness of the medications? Does he or she have the faculties and support to appropriately manage the selected regimen?

LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT

Pre-diabetes

Lifestyle intervention plays an important role in diabetes prevention, especially in high-risk groups such as those with impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance in whom blood glucose levels fall between normal and those defining type 2 diabetes (pre-diabetes). Both the Finnish Prevention Study (Tuomilehto et al., 2001) and the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP, 2003) demonstrated conclusively that intensive lifestyle interventions decreased the overall risk of diabetes by 58% in persons defined as having impaired glucose intolerance. In the Finnish Prevention Study, the rates of diabetes risk reduction were highest in people who achieved the greatest adherence to the following:

Weight reduction >5%

Fat intake <30% of total energy intake

Saturated fat intake <10% of total energy intake

Dietary fibre intake ≥15 g/1000 kcal

At least moderate intensity exercise for >4 h/week

The beneficial effects were maintained long term, with the intervention group demonstrating a 43% reduction in risk of diabetes over an average of 7 years of follow-up (Lindström et al., 2006). In the intervention group, sustained lifestyle changes remained even after individual lifestyle counselling had ended.

Diagnosed type 2 diabetes

Early in the course of the disease and in individuals in whom insulin resistance is the major pathophysiological abnormality, either energy restriction or weight loss will improve blood glucose levels. Weight loss may be less effective in terms of blood glucose control in individuals with marked β-cell dysfunction, but lifestyle interventions should still be maintained to reduce cardiovascular disease risk factors and prevent weight gain. Visceral adiposity, in particular, and its accompanying inflammatory processes contribute significantly to increased insulin resistance and vascular complication progression (Neeland et al., 2012).

With a structured lifestyle intervention program, including energy restriction, regular physical activity and frequent contact with healthcare care professionals, the majority of individuals can expect to lose 5%–10% of their starting weight. The most successful nutritional strategy for prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes is one that is personalised and that takes into consideration culture, food availability and personal preferences, but follows recommendations that encourage a variety of foods from the five main food groups each day: carbohydrates, protein, milk and dairy products, fruit and vegetables, fats and sugars. NICE recommends personalising recommendations for carbohydrate and alcohol intake, and meal patterns (NICE, 2015). In this respect, the best diets are those which work best for the individual − there is no ‘one-size-fits-all approach’.

The goal is for adequate amounts of nutrients and calories to maintain ideal weight, help stabilise blood glucose levels and assist in the maintenance of an optimal lipid profile. Extreme dietary restriction and avoidance of certain food groups might achieve short-term weight loss, but do not represent a sustainable balanced diet plan. It is more likely that weight loss is associated with adherence to diet rather than a specific type of diet (Dansinger et al., 2005). If weight loss reaches a plateau, physicians should continue to encourage the same lifestyle strategies that led to weight loss to prevent the weight regain.

Physical activity acts independently and synergistically with attempts to control weight regain achieved through nutritional interventions and may improve glycaemic control (and particularly insulin resistance) without reducing body weight. Exercise is critical in reducing cardiovascular and mortality outcomes among patients with type 2 diabetes (Wei et al., 2000); low physical activity is associated with increased arterial stiffness in patients recently diagnosed with type 2 diabetes as well as healthy controls (Funck et al., 2015). Even brief interventions to increase the dialogue between patients and healthcare providers about behavioural goals have been shown to lead to increased physical activity and weight loss (Christian et al., 2008).

There is currently a lack of knowledge concerning the optimal lifestyle intervention programmes in type 2 diabetes to ensure both compliance and long-term health outcomes. This is being addressed by the ongoing U-TURN study, which is assessing the effects of an intensive lifestyle intervention on glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes, and whether such interventions can decrease the need for anti-diabetes medications (Ried-Larsen et al., 2015).

Pharmacotherapy

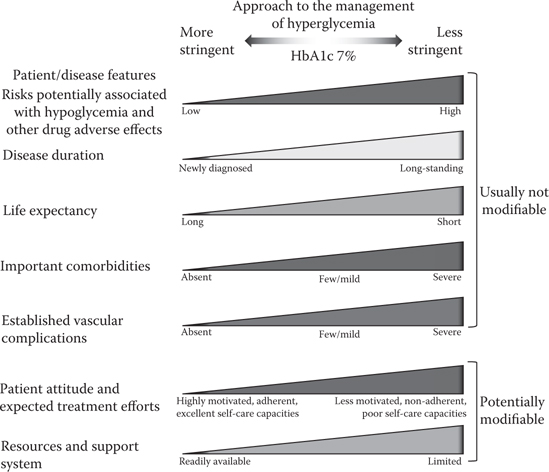

In 2015, a number of institutions and societies published updated guidelines for the management of type 2 diabetes, including NICE and ADA/EASD (Inzucchi et al., 2015; NICE, 2015). Both NICE and ADA/EASD stress the importance of personalised management, but with some differences between them. Initial HbA1c targets in the NICE guidelines are 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) for those managed with lifestyle interventions alone or lifestyle combined with a drug not associated with hypoglycaemia; for those on a drug associated with hypoglycaemia, the target is 53 mmol/mol (7.0%). ADA/EASD do not put a specific HbA1c number in their position statement, but instead highlight patients in whom goals should be more or less stringent (Figure 6.1). The strategy remains step-up, with intensification of drug or insulin dose. With NICE, this occurs when HbA1c levels are not adequately controlled by a single drug and rise to 58 mmol/L (7.5%) or higher. Unfortunately, this has echos of the old ‘waiting-for-failure approach’ and is totally inappropriate for many patients, particularly younger patients and in those more recently diagnosed. ADA/EASD advises treatment intensification if HbA1c targets are not achieved after approximately 3 months, whatever the initial target HbA1c, which seems a much more sensible approach.

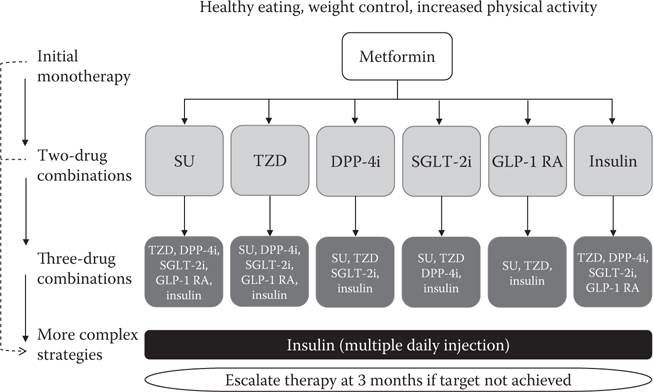

As with past guidelines, there is an assumption that in each patient with type 2 diabetes, metformin is used initially (Figures 6.2 and 6.3a) (unless not tolerated or contraindicated [Figure 6.3b]). Second-line treatments are no longer prioritised (Figures 6.2 and 6.3a). ADA/EASD propose one of the six second-line treatment options (sulphonylurea, pioglitazone, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 [SGLT-2] inhibitor, GLP-1 receptor agonist [GLP-1 RA] or basal insulin) in combination with metformin (Figure 6.2). The NICE options in combination with metformin are a DPP-4 inhibitor, pioglitazone, sulphonylurea or an SGLT-2 inhibitor (Figure 6.3a).

Both guidelines highlight the need to personalise treatment targets as well as treatment strategies, with an emphasis on patient-centred care and shared decision-making. However, this is no easy task in a complex disease such as diabetes where personalised care means implementing a treatment strategy that is in line with the patient’s preferences, specific risks and unique underlying disease pathophysiology and drug metabolism profile.

HbA1c targets should be decided with the patient after considering a number of factors, including age, current level of blood glucose control, duration of diabetes, comorbid conditions, risk of hypoglycaemia, patient motivation and ability to benefit from long-term interventions because of reduced life expectancy. Selection of the drug or drug combinations to help achieve this individual target is influenced by a number of factors as illustrated in Table 6.2.

Safety and efficacy should be given higher priorities than initial acquisition cost, as cost of medications forms only a small part of the total cost of diabetes care. In the United Kingdom, for example, therapies to treat diabetes are estimated to represent less than 8% of the total costs of the condition, with long-term complications accounting for over 80% (Table 6.3) (Kanavos et al., 2012).

The large number of available anti-diabetes therapies provides opportunities to tailor the regimen to patients’ specific needs and preferences, which should be reassessed at each review. The guideline algorithms are the starting point for treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree