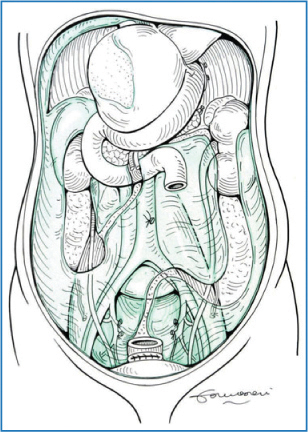

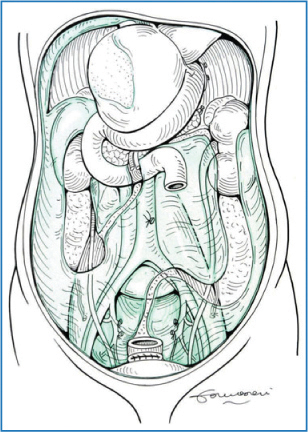

Fig. 9.1

Skin resection in repeat laparotomy includes umbilicus. Incision drawing is aimed at cosmetic umbilical reconstruction

9.3.2 Examination of the Abdominal Cavity

A complete abdominal lysis of adhesions is performed to evaluate the possibility of surgical exeresis and carcinosis extension. The latter can be classified according to different criteria, the most frequently used being the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) [2]. Exeresis of parietal and visceral peritoneum represents the fundamental step of PRT. This goal is achieved by evaluating localization, type, extension, and number of carcinomatosis implants. Proper assessment of these parameters allows correct planning of the extent of visceral exeresis and parietal PRT and identifies the most suitable techniques for implant removal and/or destruction.

9.3.3 Peritonectomy

Peritonectomy:

Removal of parietal peritoneum

Removal of visceral peritoneum (visceral and parenchymal resections)

Removal/in situ destruction of implants

Resection of abdominal wall, muscle implants, and trocar sites

Lymphadenectomy

9.3.3.1 Removal of Parietal Peritoneum

The peritoneum entirely covers the abdominal wall, pelvic cavities (Fig. 9.2) and endoabdominal organs (visceral peritoneum). Several thickenings, such as ligaments, connect visceral and parenchymal organs to each other and to the abdominal wall, thus forming anatomical recesses, including omental bursa. Carcinosis can affect all those areas and is promoted by the peculiar circulation of endoabdominal fluids and ascites, ligamentous obstacles to fluid circulation, and the possibility of ascites trapped in natural or newly formed (e.g., due to previous surgical interventions) cavities. Specific anatomical structure and function of some abdominal districts can promote the development of carcinomatosis implants. In particular, the high number of milky spots in the pelvic peritoneum and epiploon—organs for ascites reabsorption—promotes implant formation and penetration of neoplastic cells into the peritoneal lamina and underlying tissues (Fig. 9.3).

Fig. 9.2

Parietal peritoneum

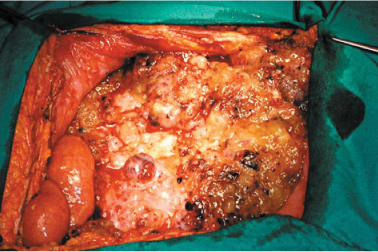

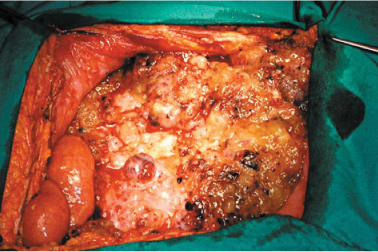

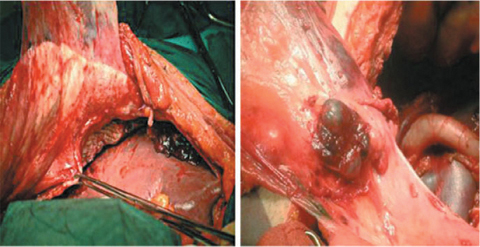

Fig. 9.3

Massive carcinomatous infiltration of the greater omentum: “omental cake”

The peritoneum is the substratum for carcinomatosis; however, it also represents an effective barrier, helping to maintain disease in the peritoneal cavity. During PRT, cutting the ligaments and complete visceral adhesiolysis represents a preliminary step necessary to evaluate disease extend and to perform HIPEC. In fact, only complete cutting of ligaments and extended removal of adherence allow adequate diffusion of HIPEC agents.

At a parietal level, exeresis comprises complete or partial removal of the peritoneum, which covers the abdominal wall, the diaphragm, and the pelvis, according to disease extension (Fig. 9.4). In the presence of carcinosis involving the parietal peritoneum, there is general consensus on the need to remove only the parietal peritoneum that presents implants, without removing unaffected areas. When the abdominal wall presents extensive and deeply penetrating disease, removal of some tracts of the musculoaponeurotic layer may be necessary (Fig. 9.5a, b). Wide peritoneal resection should be reserved to areas with extensive disease, whereas à la demande resection is suggested when implants are isolates with large areas of healthy tissue in between. If the healthy areas are limited, large peritonectomies—which can include entire anatomical sectors or even complete PRT—should be performed.

Fig. 9.4

Pelvic parietal peritonectomy

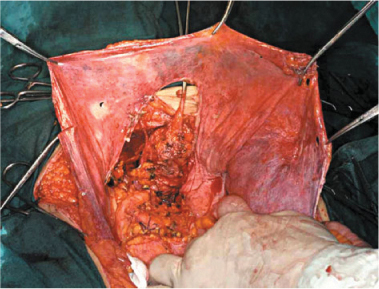

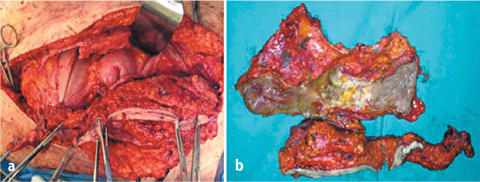

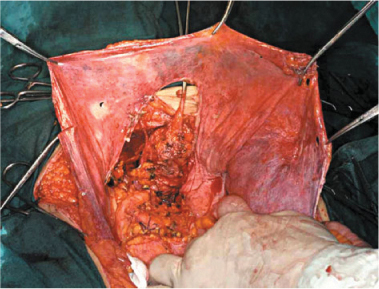

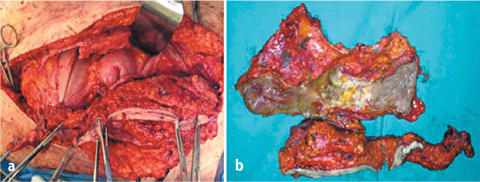

Fig. 9.5 a,b

En bloc resection of abdominal wall and ileum for carcinomatous involvement

When carcinomatosis involves pelvis and diaphragm, large excisions are required: they should comprise pelvic PRT and PRT of iliac fossae below the umbilical transverse line when the pelvis is involved, and diaphragm PRT associated with resection of the falciform and round ligament when the diaphragm is involved. Falciform and round ligament resection, in association with left hepatic triangular ligament resection, should be performed in all PRT procedures, with the aim of allowing correct placement of HIPEC catheters and optimal diffusion of chemotherapy solution.

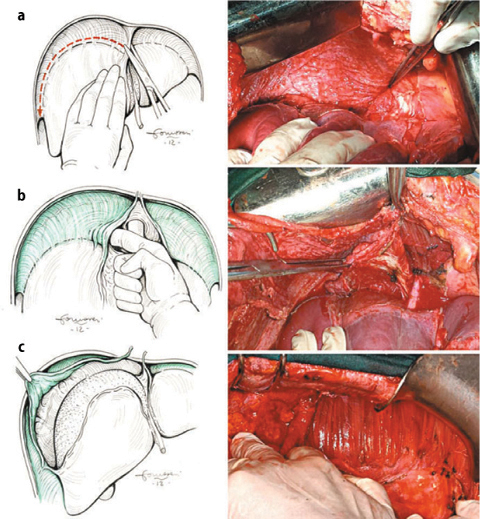

Diaphragmatic PRT is technically complex. The diaphragmatic peritoneum adheres strongly to the diaphragm and tendinous center. Therefore—especially when implants are deeply infiltrating—there is a high risk of opening the pleural cavity and it subsequently becoming contaminated by neoplastic cells. In these cases, fluid penetration into the pleural cavity should be avoided by constant use of the aspirator and by sealing the opening. When action is taken immediately and the opening is sutured, the precautionary placement of pleural drainages is not necessary. If a PRT of both diaphragms is necessary, the right and left resections should be performed separately. PRT of the right diaphragm is the more complex of the two (Fig. 9.6a–c). It begins with the sectioning of the falciform, umbilical, coronary, and triangular ligaments to allow complete liver mobilization. Sectioning of the falciform ligament up to the coronary ligament allows exposure of the precaval space and vena caval estrangement. Excision of the diaphragmatic peritoneum should begin at the margin of the laparotomy incision and continued by detaching the serous membrane from muscles and tendons, paying particular attention to preserving diaphragmatic and muscle vessels. Removing the right diaphragmatic peritoneum is completed by traction on the falciform and coronary ligaments. Glisson’s capsule is often involved: in these cases, either removing the tracts of Glisson’s capsule or in situ destruction of implants can be performed (see later chapters). The gall bladder is also frequently involved and should be removed as necessary.

Fig. 9.6

Right-diaphragm peritonectomy: hepatic mobilization (a); exposition of vena cava and right suprahepatic vein (b); stripping of the diaphragmatic perinoneum (c)

PRT of the left diaphragm is based—as for the right diaphragm—on falciform, umbilical, coronary, and left triangular ligament section. Detaching the peritoneum is begun at the left margin of the middle abdominal incision and progresses backward. Contemporary ligament traction helps in complete removal of the left peritoneum. The spleen is often involved, and in such cases, it should be removed.

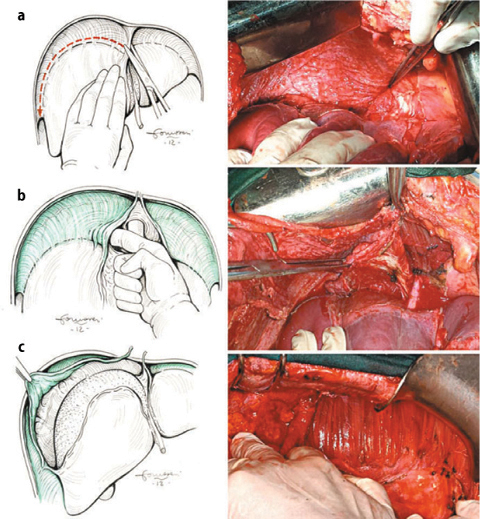

The parietal PRT comprises stripping the omental bursa peritoneum and resecting the greater and lesser omentum. Removing the greater omentum should be performed in all surgical procedures for PC. In fact, the omentum is rich in milky spots and therefore attracts neoplastic cells. Moreover, removing the greater omentum is mandatory for treating different primary tumors associated with carcinosis, such as ovarian or stomach cancer. Removing the greater omentum should be always complete and includes skeletonization of the greater curvature of the stomach. Vessels of the omentum should be ligated and cut near the gastric wall; ligation is safer than UltraCision. The right gastroepiploic vein must be cut at the intersection with the middle colic vein. Involvement of the omentum between the greater curvature and the spleen is often associated with parenchymal spleen involvement or hilar lymph node metastases: in these cases, splenectomy is mandatory (Fig. 9.7a–c)

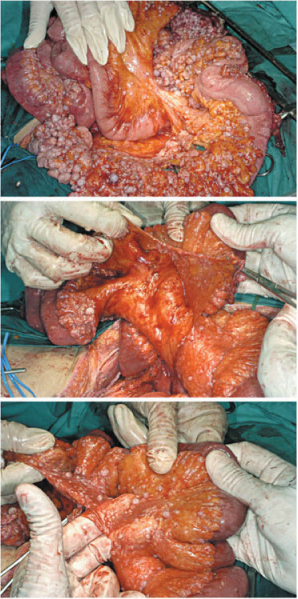

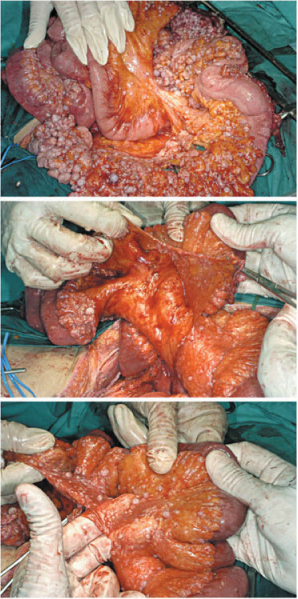

Fig. 9.7a–c

a Peritoneal carcinomatosis of the lesser and greater omentum. b Lesser omentectomy and stripping of the peritoneum from hepatoduodenal ligament. c Lesser and greater omentectomy

Lesser omentum resection should save the arteries of the lesser curvature to preserve stomach vascularization and innervation. Resection may be optionally associated with pylorotomy to control loss of tone of gastric wall. Greater omentum resection is always required and of the lesser omentum only when necessary to expose the omental bursa. Cleaning the omental bursa can also include resecting the upper sheath of the transverse mesocolon and prepancreatic peritoneum and should extend to Morrison’s pouch and the gastrohepatic ligament peritoneum when infiltrated by carcinomatosis. Resecting the peritoneum of the paracolic gutters, iliac fossae, and anterior wall does not present a technical issue; however, caution must be taken to verify integrity of the epigastric vessels to avoid postoperative bleeding (Fig. 9.8).

Fig. 9.8

Parietal peritonectomy

The pelvic peritoneum, analogously with the greater omentum, is rich in milky spots that filter and reabsorb endoperitoneal liquid. Viable neoplastic cells are thus concentrated, producing pelvic carcinomatosis. The degree of peritoneal infiltration and volume of pelvic carcinomatosis influence the strategy of pelvic cytoreduction. Simple pouch stripping without rectal resection can be performed when carcinomatosis spread is superficial. More frequently, removing pelvic and iliac fossae is associated with en bloc resection of endopelvic organs, such as female genitals and rectosigmoid colon with mesorectum (Fig. 9.9). Urinary bladder and prevesical peritoneal resection is frequent, whereas total cystectomy is exceptional.

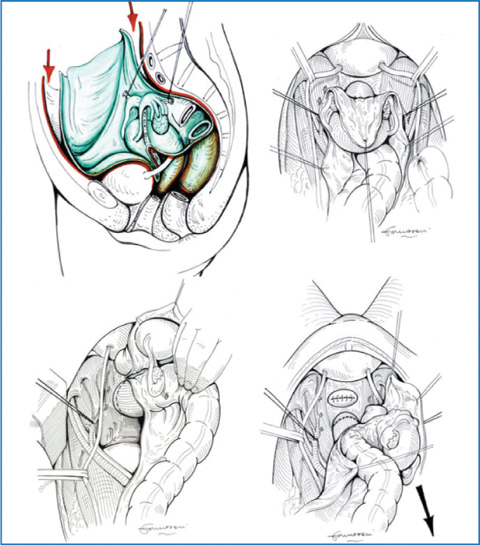

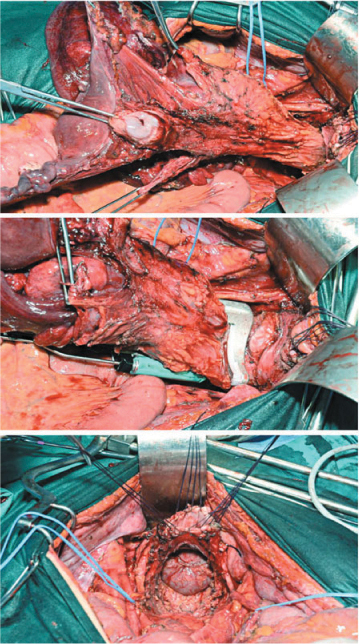

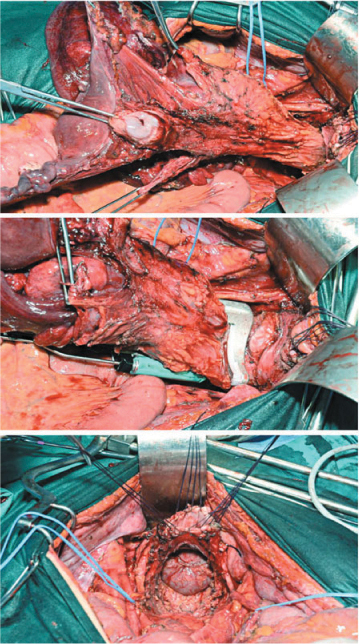

Fig. 9.9

Pelvic peritonectomy: en bloc resection of parietal peritoneum and endopelvic organs; temporary ligature of the internal iliac artery below the origin of the superior gluteal artery is optional

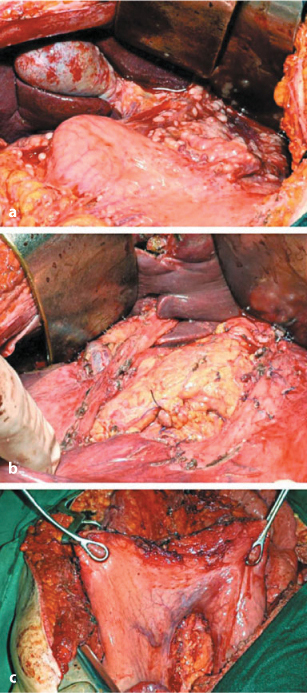

The parietal peritoneum is stripped off the posterior rectus sheath starting at the margins of the median laparotomy, round ligaments are cut (in women), and the bladder and iliac fossae peritoneum is then detached to expose the retroperitoneum. In women, ovarian vessels are ligated and cut.

Ureters are identified and underpassed with vessel loops. Iliac vessels are dissected; temporary clamping or ligation of the internal iliac artery below the origin of the superior gluteal artery may be performed to prevent major pelvic bleeding and is optionally associated with external iliac artery clamping.

Sigmoid colon and descending colon are mobilized. The inferior mesenteric artery is ligated and cut at the aortic origin, and the inferior mesenteric vein is ligated and cut at the ligament of Treitz; the descending colon is cut below the splenic flexure.

After capsizing the left colon and dissecting the rectum and mesorectum, uterine vessels are ligated where they cross the ureters. The bladder is dissected from the uterus neck, and the vagina is opened to allow complete detachment of the uterus neck. The vagina is then closed with interrupted sutures, and the anterior rectum wall is further prepared. The rectum and mesorectum are dissected up to the levator muscles; the rectum is stapled with a Roticulator, cut, and all structures are removed en bloc (Fig. 9.10).

Fig. 9.10

Pelvic peritonectomy: en bloc resection of rectum, uterus, and adnexa comprising the pouch

In patients with primary ovarian carcinomatosis, iliac-obturator lymphadenectomy is performed. In rare cases, pelvic peritoneum and, in particular, the pouch of Douglas peritoneum, can be removed, saving endopelvic structures (Fig. 9.11). The pouch peritoneum can be resected (douglassectomy) when implants are superficial. In most female patients, douglassectomy is associated with hysteroadnexectomy. Dissection of the pouch peritoneum from the rectum—sigmoid colon anterior wall should be carefully performed, avoiding opening viscera and being sure to insert muscle sutures in case of parietal injury. Stripping the peritoneum from the bladder is aided by traction of the urachus and sometimes may require partial bladder resection, in relation to implant depth, whereas the need for total cystectomy is unlikely.

Fig. 9.11

Douglassectomy

9.3.3.2 Removal of Visceral Peritoneum

The visceral peritoneum cannot be dissected from underlying layers and separately removed, which is different from parietal and diaphragmatic peritoneum. Thus, visceral PRT requires resecting viscera or organs in which peritoneal serous membrane is involved by carcinosis. Less frequently, stripping the visceral peritoneum only is an option; this occurs when carcinosis is restricted, does not deeply infiltrate the visceral wall, and is related to specific tumors (peritoneal pseudomyxoma and mesothelioma) (Fig. 9.12). Resection/destruction of single visceral implants in situ is mandatory for treating superficial carcinosis.

Fig. 9.12

Stripping of visceral peritoneum (peritoneal mesothelioma)

In primary cytoreduction, primary tumor exeresis is routinely performed with radical intent: therefore, viscera or organs with primary cancer are removed en bloc with regional lymph nodes. The initial phase of exeresis for the most frequent primary forms is represented by total gastrectomy, colorectal resection, hemicolectomy, total colectomy, and hysteroadnexectomy, all being associated in principle with total greater omentectomy, appendicectomy, and bilateral adnexectomy; resection of umbilical and falciform ligaments are routinely associated. Then, exeresis of further organs or other structures affected by carcinosis is performed: on principle all endoperitoneal organs can be removed if affected by carcinosis. Sacrificing an organ or viscus depends on carcinomatosis entity, implant size and location, and anatomic structure. Conservative treatments for bowel implants with in situ destruction are possible for small lesions and are mandatory when large resections could compromise intestinal function. When an organ or viscus is involved in massive carcinosis, its removal is recommended; splenectomy, cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, adnexectomy, and small- and large-bowel resection are the most common.

9.3.3.2.1 Liver

Hepatic implants may involve Glisson’s capsule only or infiltrate the underlying parenchyma less or more deeply. Removing hepatic Glisson’s capsule or locally destroying implants are the most frequently used techniques, whereas atypical resections of peripheral parenchyma are rarely required to remove deeply infiltrating implants. In selected cases, hepatic resection is acceptable for hematogenous metastases, as long as the lesions are single, small, and easy to resect. In selected cases with multiple hepatic metastases that are small and few, intraoperative radiofrequency could be considered. However, treating hematogenous metastases is justified only when it is possible to achieve complete cytoreduction (CC-0). The carcinosis frequently involves the ligamentum teres in its intrahepatic pathway. Resecting round and falciform ligaments should be performed in all carcinosis forms to guarantee optimal flow of chemohyperthermic solution. When a parenchymal bridge is present at the level of third inferior of the round ligament, it should be sectioned to expose the umbilical fissure of the liver and treat implants if present [3].

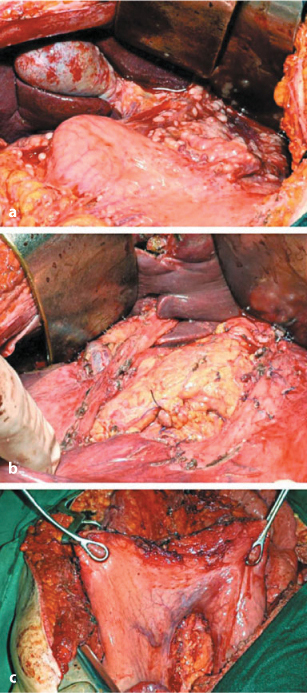

Carcinosis may involve the serous membrane of the gallbladder or hepatoduodenal ligament: cholecystectomy is mandatory, and stripping the peritoneum requires complete dissection of pedicle elements from the porta hepatis to the head of the pancreas. Only in the case of superficial carcinosis in the anterior sheath of the ligament is it technically possible to remove the serous covering or destroy in situ the implants. Direct infiltration of the elements of the hepatoduodenal ligament does not allow complete removal of implants, and the cytoreductive approach should thus be re-evaluated. Lymphadenectomy in this area is essential during PRT for carcinomatosis from primary gastric cancer and is also useful in other forms of carcinosis when lymph node involvement is evident or suspected (Fig. 9.13a, b)

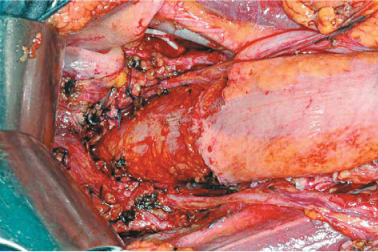

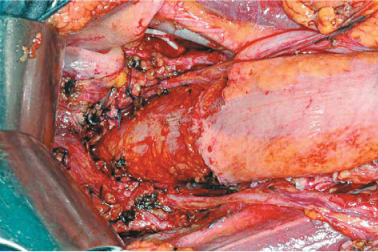

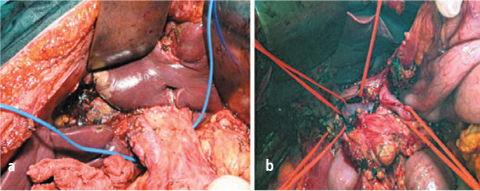

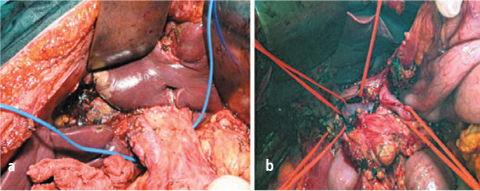

Fig. 9.13a, b

a Stripping of anterior and posterior peritoneal sheath of hepatic pedicle; b exeresis of peritoneum and lymph nodes of hepatic pedicle

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree