Introduction

Since 1850, life expectancy has increased linearly.1 With increase in life expectancy comes an increase in medical needs for adults in late life, including surgical procedures. In 2006, inpatient procedures were performed on 4358 per 10 000 patients over the age of 65 years. Surgeons have seen an increase in the rates of certain procedure types over the last decade in this age group. As an example, the rate of total knee replacements increased from 60 per 10 000 population in 2000 to 88 per 10 000 population in 2006.2 It is estimated that more than half of people currently over the age of 65 years will undergo at least one surgical procedure.3 As the population grows and ages, the need for specialized surgical care of the elderly will grow. The role of the consulting geriatric specialist is to assist the surgeon in maximizing preoperative function, minimizing the effect of comorbid diseases and preventing or managing postoperative complications.4

The approach to perioperative management of the geriatric patient begins with an understanding of age-related changes in physiology and how these changes affect stress responses. Preoperatively, the consultant should identify patients at risk for adverse outcomes, with the intent of maximizing function and minimizing risk. Although often not modifiable, intraoperative factors, such as type of procedure, type of anaesthesia and occurrence of complications, may affect the outcome in elderly patients. Prior to surgery, ways to minimize procedure length and complications should be considered by the operative team, which includes the surgeon, anaesthesiologist and consulting geriatrician. Anticipation of potential postoperative complications leads to early identification and management of adverse outcomes. The most common postoperative complications are cardiac, pulmonary and neurological in origin. Strategies to minimize the risk to these organ systems have been studied and some guidelines exist to assist with management. Prevention and treatment of infection and venous thromboembolism begin in the preoperative period and can also greatly improve outcome. Several other problems can occur postoperatively and the consulting geriatric specialist can help ameliorate those problems with simple multidisciplinary interventions.

The aim of this chapter is to guide the geriatric specialist in perioperative risk assessment and reduction with the goal of lowering complications and improving outcomes. It focuses on evaluation and management of the geriatric patient undergoing non-cardiac surgery. For a discussion on cardiac surgery in the elderly, see Chapter 42.

Outcomes of Surgery in the Elderly

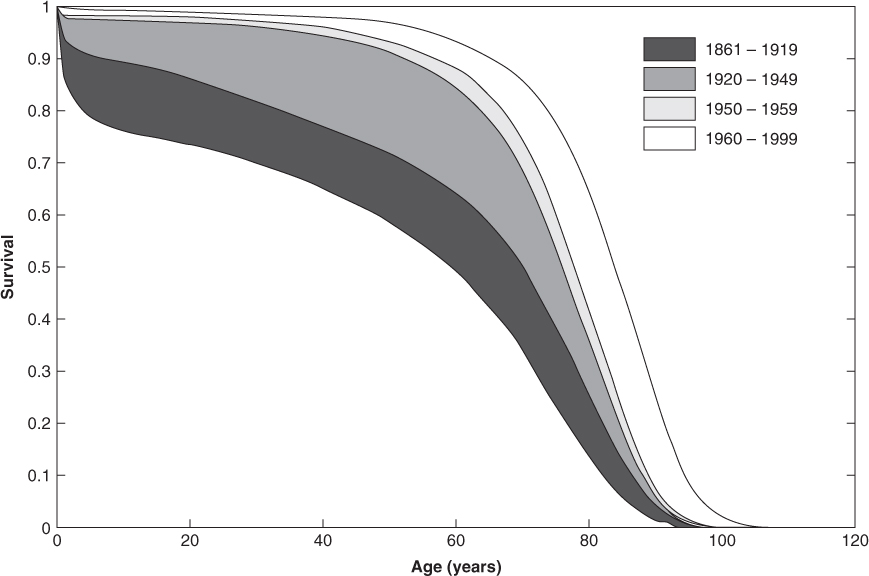

Survival curves from the UK show an increase in life expectancy with a continual rightward shift since 18501 (see Figure 127.1).5 This argues against the theory of a biologically determined limit to life. However, as mortality shifts, epidemiologists have observed a decompression of morbidity. This means that humans are living longer with more years lived in poor health.

Figure 127.1 Survival curves in Sweden over the last 140 years. Initial survival improvement trends showed a rectangularization of the survival curve, followed by parallel rightward shifts. Reprinted from Smetana,4 Copyright 2003, with permission from Elsevier.

Studies of elderly surgical patients consistently showed poorer outcomes in people over the age of 65 years versus their younger counterparts.4, 6, 7 However, when adjusted for comorbid conditions, type and length of procedure or preoperative physical state [as assessed using American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) classification or similar grading tool], the risk of adverse outcomes attributed to age alone is significantly diminished.4, 6 A description of the ASA classification system can be found on the ASA website.8 A retrospective study carried out at the end of the twentieth century showed a postoperative complication rate of 25% in patients over the age of 80 years, consistent with other studies. Although this number may be troubling, 74% of the cohort did well, with no complications, and the mortality rate was only 4.6%, down from 20% in the 1960s.9 For this reason, surgery should not be denied based solely on age. Instead, a comprehensive preoperative assessment that determines risk and maximizes function should drive decisions to proceed with surgery, even in the oldest old.

Ageing Physiology

Normal physiological changes occur with ageing. These changes should not be viewed as pathological conditions since under normal circumstances the body is able to compensate. During periods of stress, such as surgery or trauma, the ageing body is less able to counter the insult and complications may ensue.3 An understanding of normal age-related physiological changes helps the geriatric specialist to maximize functional reserve and provide adequate physiological support perioperatively. Note that although these organ system changes occur consistently with ageing, they do not occur at the same rate in each individual, such that there is often a discrepancy between the chronological age and biological age. Therefore, perioperative management must be individualized.

Age-Related Changes in the Cardiovascular System

As humans age, the physiology of the cardiovascular system undergoes numerous changes that affect vascular compliance, blood pressure and myocardial contractility. Blood vessels lose compliance due to calcification, tunica media thickening and elastic fracturing. As a result, systolic blood pressure is often elevated. However, a blunted response to baroreceptor activity predisposes the elderly to orthostatic hypotension. Changes in the peripheral vascular system cause an increase in afterload leading to myocardial hypertrophy. Cellular hypertrophy, along with calcification and fibrosis, brings about diastolic dysfunction and damage to pacemaker cells. As the ventricles stiffen, left ventricular end diastolic volume and cardiac output diminish. Increased preload with atrial enlargement compensates for the reduced cardiac output; therefore, losing atrial contraction as a result of atrial fibrillation can lead to cardiac decompensation.3, 10 Cardiovascular response to stress is also altered with age. Older people have blunted beta-adrenergic sensitivity and also reduced basal vagal tone with an inability to lower vagal tone further, leading to an inappropriate heart rate response to stress.3

Age-Related Changes in the Pulmonary System

As in the vascular system, changes in the pulmonary system associated with ageing are largely due to loss in elasticity. This loss of elastic recoil of the lungs decreases oxygen transfer and air trapping. Muscle atrophy and joint damage impair chest wall movement, further reducing ventilation and oxygenation. Vital capacity and FEV1 are decreased, in addition to ciliary function. An increase in residual volume leads to an increase in dead space during normal breathing. These age-related changes increase risk of atelectasis, aspiration and pneumonia postoperatively.3, 10

Age-Related Changes in the Renal System

Reduced cardiac output, reduced renal mass and glomerulosclerosis cause a decrease in renal plasma flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) with age. Renal clearance is slowed, affecting drug elimination and acid excretion. Patients with renal insufficiency are at higher risk of volume overload, electrolyte imbalances and drug accumulation. However, ageing kidneys also have a reduced capacity to concentrate urine, even when fluid intake is inadequate, predisposing the person to dehydration. Creatinine clearance must be calculated prior to surgery for appropriate administration of fluids, anaesthesia and pain medication.3, 10 Laboratory estimates of GFR may not be accurate in elderly populations.

Age-Related Changes in the Neurological System

The major change associated with ageing of the nervous system is loss of neuronal substance, with a decrease in brain weight. Peripheral neurons also decrease in number. This age-related loss of neuronal mass may explain the increased sensitivity to opioids and anaesthetics seen in elderly patients.

Emergency Surgery

Emergency surgery has long been associated with increased mortality rates over elective surgery.11, 12 The questions remain of whether age further increases mortality, when emergency surgery should be denied or delayed for resuscitation and if any interventions instituted prior to surgery could ameliorate the risk of mortality in the elderly.

Several observational studies have been carried out to identify the risk factors for mortality in patients undergoing emergency surgery.11–13 Most were orthopaedic, trauma or general surgery. Mortality rates were consistently higher for elderly patients and those with high ASA classes (three or higher). The leading causes of death were malignancy and septic or cardiac complications. Orthopaedic patients tended to have a more favourable outcome than general surgery patients because limb procedures are less likely to produce cardiopulmonary, metabolic or gastrointestinal (i.e. ileus) complications. Additionally, they were often labelled as ‘urgent’, meaning the operations took place within 24 h as opposed to immediate (within 1–2 h), allowing some time for stabilization and preparation.11, 12 Current guidelines recommend avoiding night-time operations; however, recent studies suggest that this may be unfounded as no association was found between late-night surgery and increased mortality.11, 12

A study restricted to elderly patients (50% over the age of 80 years) undergoing emergency abdominal surgery found that mortality rates were affected by preoperative risk (increase in comorbid conditions, high ASA class), delay in diagnosis and surgical treatment and conditions only allowing palliative surgery or non-therapeutic laparotomy. After adjusting for these conditions, age alone did not affect mortality, morbidity or length of stay.13 Emergency surgery should not be denied to patients strictly based on age.

The above studies suggest that perioperative interventions (particularly during and immediately after surgery), such as appropriate antimicrobial prophylaxis, limiting surgery length and a consideration to delay surgery for stabilization of patients with ASA class 4 or 5, may improve outcomes. Prospective studies assessing these interventions are needed.

Preoperative Medical Assessment of the Geriatric Patient

Multiple studies have been done to assess the perioperative risks of elderly patients. Several are reviewed in this chapter, with emphasis on current guidelines and recommendations. It is worth noting that although identification of factors associated with postoperative complications is helpful for risk stratification, they are often not modifiable. Additionally, although as a group patients at high surgical risk have far more complications than those at low risk, risk indices cannot predict which individual will have a poor outcome. Many patients at high risk have uneventful surgical courses. Continued research to delineate cost-effective interventions most likely to reduce adverse events that can be widely applied to the elderly surgical patient is needed.

Review of data reveals that postoperative complications, including cardiopulmonary events, neurological events or death, are more likely to occur in the setting of poor premorbid function or emergency surgery.10 Preoperative factors most likely to increase risk of morbidity and mortality include the following:9, 10, 14, 15

Based on the above factors, preoperative medical evaluation begins with a thorough history emphasizing comorbid diseases and functional status. The physical examination should focus on signs of active cardiopulmonary disease (such as jugular venous distension, rales, an S3 gallop, oedema and wheezing) and evaluation of cognitive status. Basic laboratory evaluation and radiological procedures should be obtained based on history and examination findings.10, 16 For most patients, the initial preoperative workup includes a complete blood count, electrolyte levels, renal function and electrocardiogram (ECG). It should be noted that although several sensitive risk indices exist to predict potential postoperative complications, the risk criteria are not specific. Many patients with multiple risk factors will have uncomplicated operative courses.14

Cardiac Risk Assessment

The most widely published topic in preoperative surgical evaluation is cardiac risk assessment. A PubMed search for ‘perioperative cardiac risk assessment’ brings up over 1000 articles and nearly 300 reviews. When limited to articles addressing cardiac risk in patients over 65 years of age, 500 articles and 30 reviews are listed. Current guidelines exist to aid the clinician in cardiac risk evaluation, including the 2007 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Preoperative Cardiac Risk Assessment.16 The ACC/AHA guideline utilizes the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (derived from Goldman et al.17 and Lee et al.18) for stratification and is the most widely used.

The purpose of a cardiac evaluation prior to surgery is threefold:

Table 127.1 lists unstable cardiac conditions that require stabilization prior to non-emergent surgery and strategies for management of surgical patients requiring revascularization.16

Table 127.1 Management in non-emergent surgery for unstable cardiac conditions.

| Defer surgery for management of: | Myocardial infarction within 30 days |

| Unstable or severe angina | |

| Decompensated heart failure | |

| Severe aortic stenosis (pressure gradient >40 mmHg, valve area <1 cm2 or symptoms) | |

| Symptomatic mitral stenosis | |

| Significant unstable arrhythmias | |

| Refer for PTCA or CABG if: | Stable angina and significant left main disease |

| Stable angina and triple-vessel disease | |

| Stable angina and two-vessel disease with proximal LAD lesion and EF <50% or ischaemia on testing | |

| Unstable angina (UA) or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) | |

| ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) | |

| Defer elective surgery post-PTCA for: | <14 days from balloon angioplasty |

| <30 days from bare metal stent placement | |

| <12 months from drug-eluding stent placement |

Goldman et al.17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree