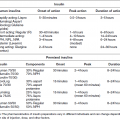

Chapter 6 George W. Taylor, DMD, DrPH; Dana T. Graves, DDS, DMSc; and Ira B. Lamster, DDS, MMSc The focus of this chapter is on the adverse effects of diabetes on periodontal health. The two major areas of emphasis are (1) discussions of the types and strength of empirical evidence from large-scale epidemiological and smaller clinical studies that support the concept that diabetes has an adverse effect on periodontal health in humans, and (2) the biologic mechanisms by which diabetes is thought to contribute to poorer periodontal health (i.e., the tissue, cellular, and molecular dynamics and their interactions). Both diabetes and periodontal diseases are globally common chronic lifestyle-related diseases [1]. The epidemiology of diabetes mellitus was presented in Chapter 2. A potentially important commonality that is increasingly becoming recognized is the association of obesity with periodontal disease as well as diabetes [2, 3]. This commonality highlights the rationale for considering periodontal disease as having an important lifestyle component in its pathogenesis [1]. The periodontal diseases are a group of chronic, microbial-induced inflammatory disease that most commonly occurs in two major forms, gingivitis and chronic periodontitis. Both forms of periodontal disease have bacterial etiologies in which Gram-negative anaerobes predominate as major periodontal pathogens. Gingivitis is a biofilm or plaque-induced inflammation of the gingiva that is reversible but can progress to chronic periodontitis, if not treated, in susceptible individuals. Gingivitis resolves clinically after mechanical disruption of the biofilm, usually by effective, regular oral hygiene. Chronic periodontitis occurs in susceptible individuals with long-term supra- and sub-gingival plaque accumulation. The chronic presence of plaque results in enrichment and maturation of the biofilm leading to sustained inflammation (or constant wounding). Chronic periodontitis is characterized by irreversible loss of the supporting tooth structures, including the connective tissue fibers of the gingiva, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. This local, irreversible destruction of periodontal tissues, in severe cases, may lead to partial or complete tooth loss [4, 5]. Like diabetes, periodontal diseases are common chronic diseases in the adult population in the United States. The prevalence of gingivitis is approximately 50% in all age groups [6]. In contrast, the prevalence of chronic periodontitis is associated with increasing age. Figure 6.1 presents the relative prevalence of moderate and severe periodontal disease (generally chronic adult periodontitis) in U.S. adults examined in the 2009–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [7]. Figure 6.1 shows that there is a gradient for the prevalence of both moderate and severe periodontal disease as age increases. This age-related gradient is due, for the most part, to the accumulated exposure over time to other risk factors. On average, the overall prevalence of moderate and severe chronic periodontal disease is approximately 30% and 8.5%, respectively, in the United States. Figure 6.1 Prevalence of moderate or severe periodontitis in US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2010 [7]. % Moderate: Moderate periodontitis is defined as 2 or more teeth with attachment loss greater than or equal to 4 mm, or 2 or more teeth with probing pocket depth greater than or equal to 5 mm at the interproximal sites. % Severe: Severe periodontitis is defined as 2 or more teeth with attachment loss greater than or equal to 6 mm, and 1 or more teeth with probing pocket depth greater than or equal to 5 mm at interproximal sites. The evidence we will consider with regard to the adverse effects of diabetes on periodontal health comes from English language reports of studies conducted in numerous parts of the world. As might be expected, reports in the literature provide answers to different kinds of questions, and vary in their ability to help us establish and understand causal associations between diabetes and periodontal diseases. In terms of study designs’ contributions to inferring causal relationships, cross-sectional studies are limited to studies of prevalence, extent, and severity. Because cross-sectional studies cannot establish temporal relationships, they are limited in providing evidence of causal relationships. In contrast, studies following individuals over time (i.e., prospective cohort or longitudinal studies) allow quantification of the risk of diabetes contributing to worsening periodontal health using any of the terms associated with the passage of time (i.e., incidence and progression) and can allow for inferences regarding causal relationships. Several comprehensive narrative reviews [8–12] and three meta-analyses [13–15] have evaluated the body of literature for original research reports to assess the adverse effect of diabetes on periodontal health. The narrative reviews and the meta-analyses consistently conclude that diabetes adversely effects periodontal health in people with diabetes. Tables 6.1 and 6.2 illustrate a way in which conclusions from reviews of the body of literature can be organized. These tables summarize the relative proportionate numbers of studies by study design (i.e., cohort and cross-sectional/descriptive) for each category of diabetes typically considered in reviews of the literature. These two tables are derived from the compilation of two comprehensive narrative reviews evaluating reports published between 1967 and 2007 [11, 12]. Table 6.1 Effects of diabetes on periodontal health. Conclusions of the 89 studies that include a non-diabetes control group [16]. The numerator represents the number of studies reporting diabetes having an adverse effect on periodontal health, the denominator the total number of studies in each group. Table 6.2 Effects of diabetes on periodontal health. Conclusions of the 61 studies that include participants with both better and poorer glycemic control [16]. The numerator represents the number of studies reporting poorer glycemic control having decreasing adverse effect on periodontal health, the denominator the total number of studies in each group. Table 6.1 summarizes the conclusions of studies reported in the literature that address the question of whether diabetes adversely affects periodontal health, comparing people with and without diabetes. The column headings indicate the type of diabetes included in the study and the row headings indicate the type of study design (i.e., cohort or cross-sectional/descriptive). In each category within Table 6.1, the numerator is the number of studies confirming that diabetes adversely affects one or more of several measures of periodontal health (e.g., gingivitis, probing pocket depth, attachment loss, or radiographic bone loss). The denominator represents the total number of studies of that particular kind (e.g., cross-sectional studies with participants having type 2 diabetes). For example, all four of the reports from cohort studies that included people with type 2 diabetes concluded that periodontal health was worse in people who had diabetes than in those without diabetes. The information presented in Table 6.1 shows the vast majority of reports, specifically 79 of 89 studies, provided evidence that diabetes adversely affects periodontal health. The stronger evidence comes from the cohort studies with all seven reports supporting a conclusion that diabetes had an adverse effect on periodontal health. An updated review of the body of literature published from 1967 to 2011 found 101 of 115 reports concluding diabetes had an adverse effect on periodontal health (Table 6.3). In Table 6.3, proportions for the types of study designs, the types of diabetes included in the studies, and studies with positive results are relatively consistent with the earlier summary of published reports shown in Table 6.1. Table 6.3 Effects of diabetes on periodontal health. Conclusions of the 115 studies that include a non-diabetes control group for the period from 1967 to 2011. The numerator represents the number of studies reporting diabetes having an adverse effect on periodontal health, the denominator the total number of studies in each group. Table 6.2 illustrates another way of organizing the literature to address the question of whether the degree of control of diabetes (i.e., glycemic control) is associated with poorer periodontal health. In this type of analysis the participants can be limited to people with diabetes who have better or poorer glycemic control. The degree to which diabetes is controlled or managed is usually assessed by measuring the amount of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in the blood. HbA1c is an indicator of persisting hyperglycemia over the previous 60–90 days. For many people with diabetes the therapeutic target for good glycemic control is to achieve an HbA1c level that is 7% or less [17]. Table 6.2 summarizes the conclusions of studies that provided information comparing the effects of better or poorer glycemic control on periodontal health in people with diabetes. Similar to Table 6.1, the evidence was derived from both cohort and cross-sectional original research reports published between 1967 and 2007 [11, 12]. A large majority (two-thirds) of the studies in Table 6.2 concluded that people with poorer glycemic control had worse periodontal health than those with better glycemic control (42 of the 61 studies). Again, the stronger evidence comes from the set of cohort studies that followed people over time, allowing for more definitive conclusions regarding a causal relationship. Eight of the 10 cohort studies supported the conclusion that poorer glycemic control leads to poorer periodontal health over time. From the information provided in Tables 6.1 to 6.3 and persisting to the present, the preponderance of studies reporting on the adverse effects of diabetes are cross-sectional and involve convenience samples of patients, principally from hospitals and clinics. A smaller subset of longitudinal and population-based studies provides additional support for the association between diabetes and periodontal disease. In extending our capacity to assess the body of evidence beyond comprehensive narrative reviews, meta-analyses provide the opportunity to combine the results of several studies and quantitatively summarize the results. Chavarry et al. (2009) published a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association of diabetes with poorer periodontal health and whether diabetes has an adverse impact on the response to periodontal treatment in 49 cross-sectional studies and eight cohort studies [13]. This meta-analysis found statistically significant greater mean clinical attachment loss and probing pocket depth in cross-sectional studies of people with type 2 diabetes compared to those without diabetes (P = 0.021 and P = 0.046 respectively). While not statistically significant and probably not clinically significant, the meta-analysis showed a tendency for people with type 1 diabetes in cross-sectional studies to have greater mean attachment loss than people without diabetes (P = 0.54) and greater mean probing depths (P = 0.137). The authors of this meta-analysis suggested that the lack of a statistically significant association of type 1 diabetes and poorer periodontal health could be explained by the low mean age of the participants with type 1 diabetes (between 11 and 15 years) and the concomitant observation that people in this age group do not frequently develop destructive periodontal disease. It should also be noted that this meta-analysis did not conduct analyses that distinguished between those with better and poorer controlled diabetes. This may have also limited their ability to find a significant difference in those with type 1 diabetes. Although the meta-analysis by Chavarry et al. did not find a statistically significant impact of diabetes on periodontal health in those with type 1 diabetes, one rigorously conducted study of children and adolescents 6–18 years old who predominantly had type 1 diabetes found significantly poorer periodontal health in those with diabetes than the control group without diabetes [18–20]. In one report the investigators found statistically significant and clinically meaningful four-fold higher prevalence of teeth with clinical attachment loss in children with type 1 diabetes [20]. In another report the investigators considered the degree of glycemic control over a two-year period prior to the periodontal examination. In that report the investigators found statistically significant greater periodontal destruction in the participants with diabetes than the controls without diabetes, even when divided into two subgroups of 6- to 11-year-olds and 12- to 18-year olds [19]. In another analysis, HbA1c was significantly associated with the degree of periodontal destruction, suggesting the need to account for glycemic control in investigations of relationships between diabetes and periodontal diseases in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes [18]. Chavarry and colleagues’ systematic review also investigated eight longitudinal studies; four assessed differences in the progression of periodontal disease between people with diabetes and those without and the effect of diabetes on the response to periodontal treatment. For the three longitudinal studies of participants with type 1 diabetes [21–23], one of the two studies of the progression of periodontal disease found the progression to be more pronounced in those with type 1 diabetes [21]. In the study that investigated diabetes effects on the response to periodontal therapy, there was no significant difference in improvements of periodontal outcomes between those with and without diabetes [23]. In Chavarry and colleagues’ systematic review of the progression of periodontal disease in type 2 diabetes, of the three studies included [24–26], two studies reported greater progression of periodontal disease [25, 26]. The study assessing the effect of diabetes on the response to periodontal treatment showed worsening of periodontal health at six months follow-up was greater in the participants with diabetes than in those who did not have diabetes [24]. In two studies investigating the response to periodontal treatment that included participants with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, neither found differences in the changes to clinical periodontal outcomes after four months [27] and five years follow-up [28]. Additional evidence supporting diabetes having an adverse effect on periodontal health comes from studies of women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Gestational diabetes is defined as any degree of glucose intolerance, that is clearly not overt diabetes, with onset or first recognition during pregnancy [17]. Approximately 7% of all pregnancies are complicated by GDM [29]. For many women the impact of GDM goes beyond the end of the pregnancy. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 studies found women who had GDM to have at least a seven-fold greater risk for developing type 2 diabetes in the future than women who had a normoglycemic pregnancy [30]. Evidence is emerging that GDM contributes to poorer periodontal health during the pregnancy. Five studies published in English since 2006 have included pregnant women with and without GDM to evaluate the role of GDM as a risk indicator for periodontal disease [31–35]. The prevalence of periodontal disease ranged from 31% to 77% in women with GDM or a history of GDM and from 13% to 57% in women who had no history of GDM. Four of the five studies, conducted in Thailand (31) and the United States [33–35], concluded that GDM was significantly associated with poorer periodontal health. These four studies estimated 2.6- to 9-fold greater odds of having periodontal disease for women with a history of GDM than women who had not had GDM. The other study, conducted in Brazil [32], did not find a significant difference in the prevalence of periodontal disease in women with and without GDM. This is an emerging body of evidence that will benefit from subsequent prospective studies to strengthen causal inferences. The studies reviewed in this section provide an overview of the evidence supporting the conclusion that diabetes has an adverse effect on periodontal health in susceptible individuals. The studies included in the reviews were conducted in different settings and different countries, with different ethnic populations and age distributions, and with a variety of measures of periodontal disease status (i.e., gingival inflammation, pathologic probing pocket depth, loss of periodontal attachment, or radiographic evidence of alveolar bone loss). The studies used different parameters to assess periodontal disease occurrence (prevalence, incidence, extent, severity, or progression). Hence, this inevitable variation in methodology and study populations limits the possibility that the same biases or confounding factors apply in all the studies and provides support for concluding that diabetes is a risk factor for periodontal disease incidence, progression, and severity. In addition, there is substantial evidence to support a “dose-response” relationship (i.e., as glycemic control worsens, the adverse effects of diabetes on periodontal health become greater). Finally, there are no studies with superior design features to refute this conclusion. This section reviews the biologic mechanisms that can explain the increased prevalence and severity of periodontal disease in people with diabetes. As with other complications of diabetes, biologic mechanisms important in diabetes-associated periodontitis are probably multi-factorial, arising from the altered cellular and molecular interactions due to the metabolic dysregulation that characterizes diabetes. The mechanisms to be considered in this section include altered subgingival microflora, altered host inflammatory response, advanced glycation end-product formation (AGEs) and their receptor (RAGE), uncoupling of bone resorption and bone formation, and several other mechanisms less frequently mentioned. Understanding the explanatory mechanisms leading to more frequent and more severe periodontal infection in diabetes involves synthesis of observations from these multiple perspectives. Sources providing major contributions to the content of this section on the biologic mechanisms include extensive reviews in journal articles [8, 11, 36] and book chapters [12, 16]. The question of whether diabetes contributes to a periodontal sulcular microflora that has a different composition and is more virulent due to elevated sulcular glucose levels has been studied since the 1980s. An extensive review of studies investigating the impact of diabetes on the periodontal microflora suggests neither diabetes nor the degree of glycemic control has an established, significant effect on the periodontal microflora [36]. The authors of that review recognize the limitations of the studies reviewed in this body of literature generally include inadequate control groups and restricted analysis of the dental plaque or biofilm species. The review’s authors suggest that techniques of microbiomics and metagenomics could, in the future, provide a different perspective on the influence of diabetes on the oral microbiome. An example of application of such techniques is a report by Casarin and colleagues using 16S rRNA gene cloning and sequencing [37]. In that report investigators found significant dissimilarities in the subgingival biodiversity of participants who had severe generalized chronic periodontitis when comparing those with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes (n = 12) to those who did not have diabetes (n = 11). Whereas the evidence for diabetes having an effect on the periodontal microbiome is inconclusive, evidence that diabetes contributes to an altered host response to the periodontal bacterial challenge is more compelling. A number of earlier investigations reported that diabetes contributes to impaired neutrophil function. The reports indicate that impaired chemotaxis [38–44], adherence [45, 46], phagocytosis, and bacteriocidal activity [47–49] could result in greater propensity for colonization and proliferation of periodontal pathogens in the dental plaque biofilm. Additional evidence also suggests that chronic hyperglycemia in diabetes contributes to defects in neutrophil function that mediate diabetes-related tissue damage to the periodontium by stimulating exaggerated production of inflammatory mediators and superoxide release by neutrophils, enhanced leukocyte rolling and attachment to the vascular endothelium in periodontal vessels, and impaired transendothelial migration [50, 51]. Neutrophils in patients with diabetes who have severe periodontitis have also been shown to have defective apoptosis, leading to longer retention of neutrophils in the periodontal tissue and prolonged and greater tissue destruction by continued release of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [52]. Metabolic routes linked to leukocyte dysfunction include advanced protein glycosylation, the polyol pathway, oxygen free radical formation, and the nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate pathway [53].

Periodontal disease as a complication of diabetes mellitus

Periodontal diseases: overview

Evidence of adverse effects of diabetes mellitus on periodontal health

Study design

Diabetes mellitus type

Total number of studies

(number with effect/number of all studies)

Type 1

Type 2

Type 1 or 2

Gestational (GDM)

Type not reported

Cohort

3/3

4/4

0/0

0/0

0/0

7/7

Cross-sectional, descriptive

22/23

20/23

15/18

3/3

11/15

72/83

Total:

25/26

24/27

15/18

3/3

11/15

79/89

Study design

Diabetes mellitus type

Total number of studies

(number with effect/number of all studies)

Type 1

Type 2

Type 1 or 2

Type not reported

Cohort

4/4

3/3

1/3

0/0

8/10

Cross-sectional, descriptive

11/18

15/17

7/11

1/5

34/51

Total:

15/22

18/20

8/14

1/5

42/61

Study design

Diabetes mellitus type

Total number of studies

(number with effect/number of all studies)

Type 1

Type 2

Type 1 or 2

Gestational

(GDM)

Type not reported

Cohort

3/3

5/6

0/0

0/0

0/0

8/9

Cross-sectional, descriptive

26/28

35/38

15/18

3/3

14/19

93/106

Total:

29/31

40/44

15/18

3/3

14/19

101/115

Biologic mechanisms contributing to the adverse effects of diabetes on periodontal health

Altered subgingival microflora

Altered host inflammatory response

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree