Fig. 7.1

Depiction of anatomy in the midsagittal plane along with two approaches for RPP. BL bladder, P prostate, RH rhabdosphincter, RU rectourethralis; puboprostatic complex consists of puboprostatic ligaments (PPL—red); intermediate pubourethral ligament (yellow) and anterior pubourethral ligament (PUL—green). Note the dorsal vein of penis continuing over prostate as DVC

Nomenclature of Fasciae Around the Prostate (Fig. 7.2)

Fig. 7.2

Prostate with its covering fasciae. The levator ani (LA) fascia (purple) is the parietal endopelvic fascia which reflects over the prostate as visceral endopelvic fascia to fuse with the lateral prostatic fascia (LPF—green). The Denonvillier’s fascia (DF) proper (red) is located on the posterior aspect of prostate. Another ventral layer of DF is actually the ventral rectal fascia (blue). The main bulk of neuronal tissue passes at the confluence of these fascia between the layers. Modified from Costello et al. Immunohistochemical study of the cavernous nerves in the periprostatic region. BJU Int. 2011 Apr;107(8):1210–5. With permission from John Wiley and Sons

The ventral rectal fascia (posterior layer of Denonvillier’s fascia): As we go in the space between the anal canal and the bulb of the penis over the surface of external anal sphincter toward the prostate, after division of the rectourethralis muscle, we encounter the prostate covered with a shiny fascia which is the ventral rectal fascia or the fascia propria of the rectum (wrongly called the posterior layer of Denonvillier’s fascia) [4]. This fascial layer covers the ventral surface of the rectum and is continuous with the lateral rectal fascia which covers the lateral aspect of rectum. It descends in front of the rectum behind the prostate to fuse with the perineal body. As we cut the rectourethralis by keeping a downward traction over the surface of the anal canal, the space between the prostate and the rectum opens up with the ventral rectal fascia staying over the prostate.

Denonvillier’s fascia (anterior layer of Denonvillier’s fascia): It is derived from embryonic fusion of the two layers of peritoneum of the prostatorectal cul de sac. These layers are not actually separable. While descending behind the bladder, it loosely covers the seminal vesicles but lower down is densely adherent to the underlying prostate. It usually extends up to the apex of the prostate.

Lateral pelvic fascia: It is the fascia covering the medial surface of the levator ani and is actually the parietal layer of endopelvic fascia [5].

Lateral prostatic fascia: It is the fascia immediately surrounding the prostate especially anteriorly and laterally. Posteriorly it is fused with and is inseparable from Denonvillier’s fascia. Some consider this fascia to be a multilayered [4] visceral component of endopelvic fascia. This contains some nerve fibers that form the accessory distal neural pathways (see later) of the cavernous nerves and is preserved in “veil of Aphrodite” technique [6].

Prostatic capsule: There is no true capsule over the prostate. A fibromuscular tissue surrounds the prostate which is indistinct from and is a part of underlying prostatic stroma [5].

The Anatomy of the Puboprostatic Complex

Puboprostatic complex refers to the structures between the pubic symphysis and the anterior aspect of the prostate and proximal urethra. It is responsible for keeping the prostate and proximal urethra suspended behind the pubic symphysis (Fig. 7.1). Steiner [7] and Wimpissinger et al. [8] independently studied the anatomy of the puboprostatic complex in detail during surgical as well as cadaveric dissections. It consists of (i) puboprostatic ligaments (or the posterior pubourethral ligaments): they are the most proximal pyramidal structures and are said to be lying in a horizontal plane keeping the bladder neck and the proximal prostate suspended to the pubic symphysis, (ii) the DVC: it is the continuation of dorsal vein of penis into the retropubic space and runs beneath the pubic arch separated from the anterior surface of prostate by the (iii) fibromuscular connective tissue (or the intermediate pubourethral ligament): this fibromuscular soft tissue connects the anterior commissure of the prostate to the undersurface of the pubic wall. It is oriented in a vertical plane and together with the puboprostatic ligament, forms a “T”-shaped structure (iv) the pubourethral ligament proper (or the anterior pubourethral ligament) which holds the membranous urethra suspended. During the perineal approach, while dissecting at the prostatic apex, when the urethra is transected, the anterior pubourethral ligament is left undisturbed attached with the urethra and we enter the retropubic space. The insertion of the straight Lowsley through the transected apex helps downward rotation of the prostate to bring anterior prostatic surface in view. Here we bluntly separate the intermediate pubourethral ligament and further push the DVC away from the prostatic surface to allow working in an avascular plane (Fig. 7.3).

Fig. 7.3

With straight Lowsley tractor depressed toward rectum, space can be created on the anterior surface of prostate (arrow). With the prostate thus rotated, the DVC automatically remains away from surgical field. Note the anterior pubourethral ligament (green) still attached to the urethra keeping it suspended

This step has two major implications, namely, avoidance of DVC, resulting in less blood loss as compared to other approaches, and preservation of urethral suspensory mechanism which helps in achieving good “early continence” rates.

The concept of preservation of the urethral suspensory mechanism for improvement of the continence rates during the retropubic approach was introduced in the early 1990s [9]. However, it was always a natural part of the perineal approach since it leaves the pubourethral ligament anatomy undisturbed from its attachment on the pubic bone by virtue of dissection on the surface of prostate.

The Anatomy for Nerve Preservation

The neuroanatomy relevant to nerve preservation during radical prostatectomy is still evolving. Even after Walsh and Donker’s “discovery” [10] and wide application of the technique of preservation of neurovascular bundles (NVB) in the years that followed, the outcomes of erectile function were variable (56–93 %) [11]. The traditional concept that the cavernous nerves arise from the pelvic splanchnic nerves and autonomic plexus in front of and lateral to the rectum at the level just above the seminal vesicles and travel caudally in “cord-like” NVB on the posterolateral surface of prostate has been modified by recent anatomical studies. Takenaka and Tewari [12], in a review of contemporary anatomical studies, described that the relevant neural tissue encountered during radical prostatectomy rests in three zones (the “Trizonal” concept) (Fig. 7.4). The zones are: (i) proximal neurovascular plate (PNP): The neural tissue arising from the pelvic splanchnic nerves is located in a broad area extending from underneath the seminal vesicles to laterally over the lateral rectal fascia. This plate of tissue carries all the candidate fibers of the cavernous nerves, which cannot be identified surgically, and hence the entire broad plate needs to be preserved at this proximal level. Distally, ome fibers converge to form the (ii) predominant neurovascular bundle (PNB), which is the classically described NVB travelling on the posterolateral surface of the prostate. A few other fibers remain divergent over the lateral prostatic fascia as (iii) accessory distal neural pathways (ANP) and form an additional conduit for neural transmission. An earlier anatomical study by the same author on 14 formalin fixed male cadavers found that the pelvic splanchnic nerves does not solely carry parasympathetic fibers as earlier thought, but also consists of up to 36 % sympathetic fibers and consequently the nerves in the above-described zones are also contributing to the continence mechanisms in addition to erectile function [13].

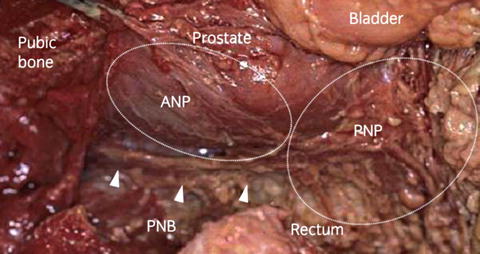

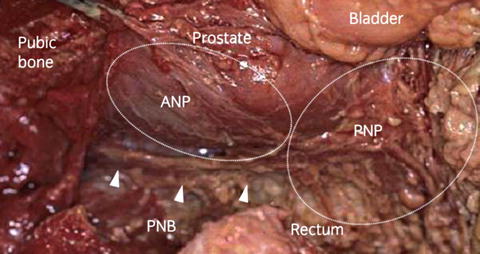

Fig. 7.4

Neuronal structures around prostate as visualized during robotic surgery. The “Trizonal concept” of Taenaka and Tewari. PNP proximal neurovascular plate (overlying the rectum), PNB predominant neurovascular bundle (posterolaterally), ANP accessory distal neural pathways (over the lateral surface). From Takenaka A., Tewari AK. Anatomical basis for carrying out a state-of-the-art radical prostatectomy. International Journal of Urology (2012) 19, 7–19. Reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons

NVB preservation alone might be giving variable results as the other two zones are not preserved. Better erectile function claimed in other techniques like high anterior release [14] and “veil of Aphrodite” nerve preservation [15] can be ascribed to respecting these evolving anatomical concepts. Another immunohistochemical study of periprostatic areas on cadavers however contradicts these findings by concluding that between 3 and 9 o’clock there is hardly any significant parasympathetic nerve distribution and that there is no anatomical evidence to practice these higher incisions [16]. A limitation of the study however was that only four cadavers were studied, two fresh and two fixed. The nerve sparing technique in RPP as described by Weldon, although not yet studied as extensively as it has been for other approaches, respects the above anatomical description and is mentioned later.

Indications

Traditionally, RPP has been advocated either when lymphadenectomy could be safely omitted, i.e. low-risk disease where risk of positive nodes would be less than 5 % according to Partin’s tables (serum PSA less than 10 ng/ml, up to T2a disease, Gleason 6 or 3 + 4 = 7) or when laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy was performed along with RPP. Now that the technique of pelvic lymphadenectomy has been developed, it has the potential to broaden the indications to include almost all patients choosing surgical treatment for localized prostatic cancer.

Some special circumstances where perineal approach is particularly suitable are:

Inability to put the patient in extended lithotomy position would form the only absolute contraindication to this approach. Performing RPP in very small prostate (<20 g), very large prostate (>100 g), and post radiation salvage situations is challenging but not contraindicated.

Preoperative Preparation

On the day prior to surgery, a thorough bowel preparation is given. Antithrombotic stockings and pneumatic compression stockings should be applied prior to surgery. A second generation cephalosporin is used for antibiotic prophylaxis. Blood typing and cross matching are done to keep blood arranged if needed.

Instruments

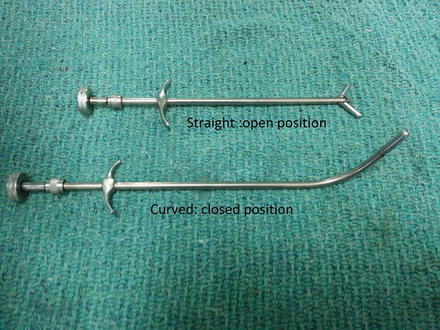

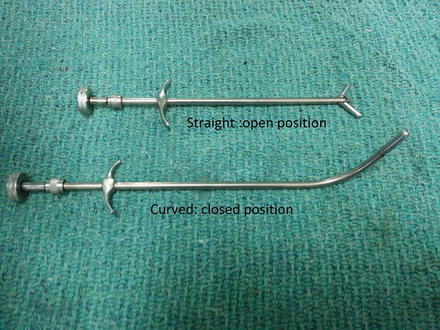

A set of curved and straight Lowsley tractor (Fig. 7.5) are the only special instruments needed to perform the prostatectomy proper. However, for performing the lymphadenectomy through the same incision, a self-retaining retractor system such as Omnitract™ with various blades and a headlight is absolutely essential.

Fig. 7.5

Lowsley tractor

Technique

Position

Patient is positioned in an exaggerated lithotomy position with buttocks protruding from the edge of the table. A rectal shield is placed to facilitate repeated rectal examinations for rectal wall assessment during the surgery to avoid getting in the anal canal or rectum. A curved Lowsley tractor is passed into the bladder and its wings are opened to allow maneuvering the prostate in various stages of dissection. The scrotum is then fixed with sutures so as to prevent falling in front of the perineum.

Approaching the Prostatic Apex

A curved incision is given 2 cm from the anal verge from 9 o’clock to 3 o’clock position remaining medial to the ischial tuberosities. After incising the subcutaneous tissue, bilateral ischiorectal fossae are developed by bluntly entering the index fingers in the visible fat and directing the fingers toward the toes of the operating surgeon (Fig. 7.6a). When in proper space, one should be able to feel the rectum between the two index fingers. Central tendon is then identified and divided (Fig. 7.6b). One can then identify the circular fibers of the anal sphincter (Fig. 7.6c).

Fig. 7.6

(a) Developing bilateral ischiorectal fossae. (b) Division of the central tendon. (c) Artery forceps passed beneath the circular fibers of external anal sphincter (superficial part)

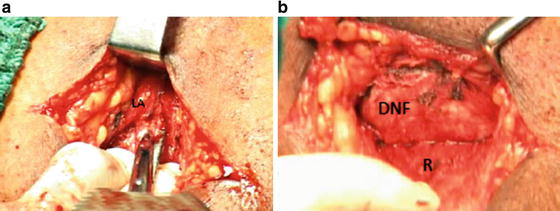

Two popular approaches for reaching the apex of the prostate from here are the traditional Young approach (suprasphincteric) and Belt (subsphincteric) approach. With the Belt approach there is more chance of anal sphincteric incontinence [2]. With sharp and blunt dissection in the midline between the anal canal and the bulb of penis, the fibers of rectourethralis are identified and sharply divided transversely not deviating from the midline (Fig. 7.7a). The direction of this dissection is not parallel to the floor but slightly upward toward the apex of the prostate which can be identified by gently shaking the Lowsley toward and away from the abdomen. Once the apex is identified, the rectum can be swept in caudad direction with the help of Kittner dissector to expose the shiny Denonvillier’s fascia of the prostate (Fig. 7.7b).

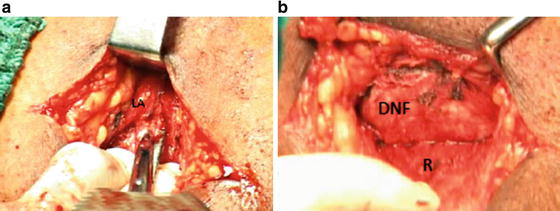

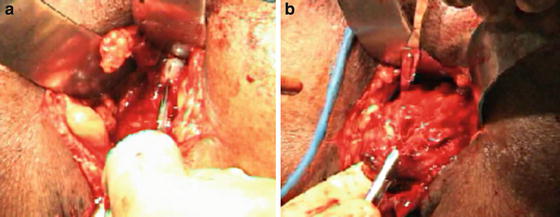

Fig. 7.7

(a) Division of the rectourethralis (note the slightly upward direction of the scissors). (b) Denonvillier’s fascia (DNF) over the prostate. LA levator ani, R rectum

One of the common modes for the rectum to get injured is when the assistant depresses the curved Lowsley tractor in order to bring the prostate toward the wound, thereby tenting the rectum further (Fig. 7.8). A useful modification to the technique of exposing the prostate is the delayed introduction of curved Lowsley after the rectourethralis is divided [21]. This prevents any distortion of the anatomy at this stage as the rectum most commonly gets injured before the prostate is exposed [3].

Fig. 7.8

Assistant’s downward traction over the curved Lowsley (towards abdomen) in order to bring the prostate towards the incision for better view during apical dissection leads to a tented anal canal and makes it more prone to injury.

Mobilization of the Lateral Surfaces and Base of Prostate

Laterally on either side the prostate is closely invested by levator ani muscles. Space can be created by inserting the finger bluntly between the prostate and the levator muscle (Fig. 7.9). This is facilitated by turning the curved Lowsley tractor to the side of the lateral surface being freed in order to push the prostate to the opposite side to open up this space.

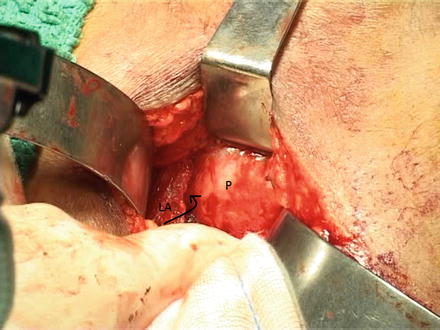

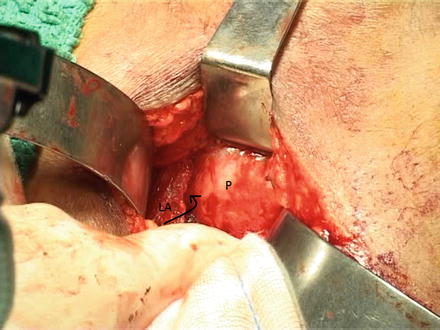

Fig. 7.9

Finger dissection between prostate (P) and levator ani (LA) creates a space between them

The assistant is then asked to hold the Lowsley inferiorly toward the surgeon so that the prostate is held in a “hung up” position (Jewett maneuver) which facilitates development of space between the base of the prostate and seminal vesicles, covered with Denonvillier’s fascia, and the rectum. Constant caudad traction over the rectum with a thin Deaver is required and using either two Kittner dissectors or a gauze piece wrapped over a suction tip pushed slowly between the rectum and the prostate, a space is developed [20]. While doing this the lateral prostatic pedicles that come into view can be put to stretch by moving the Lowsley tractor to either side and can be ligated or clipped and divided. Having cleared the pedicles, one can feel the open blades of the Lowsley tractor at the bladder neck laterally and the vesicoprostatic junction can be defined all around except anteriorly.

Dissecting Seminal Vesicles

Traditionally this step was performed after transection of the bladder neck but all contemporary techniques emphasize on dissecting out seminal vesicles prior to opening the bladder if possible. This preference has developed after it was theorized that incomplete removal of Seminal Vesicles (SVs) during RPP is responsible for higher incidence of early biochemical recurrence (BCR) [22]. After development of space between the rectum and prostate and beyond the base of prostate, the Denonvillier’s fascia overlying the SVs is incised transversely exposing the SV and vas deferens. With the help of a Mixter forceps, each vas is hooked out, clipped, and divided as proximally as possible followed by dissection and delivery of the seminal vesicles one by one after dealing with the seminal vesicular artery at the tip of each SV [23].

Dissection of Apex and Intraprostatic Urethral Dissection

At the apex, the urethra can be palpated over the Lowsley tractor where it exits the prostate. It can be encircled with a right angled forceps in this area. While doing this, the dorsal vein is automatically pushed dorsally away from urethra. The prostate often, especially if large, overhangs the membranous urethra by a few millimeters at the apex. Dissection within this overhanging prostate is required in such cases to get to the true prostatomembranous junction before its division. This is easily accomplished by gentle use of a right angled forceps to dig out the true prostatomembranous junction. The importance of preserving the urethral length proximal to rhabdosphincter was always insisted but recently it has been seen that it can safely be preserved up to verumontanum without compromising the oncological outcome and this helps in significant improvement of early continence at 3 months [24].

Transection of the Urethra and Anterior Dissection

At the prostato-urethral junction, the posterior wall of urethra is divided transversely with a no. 15 blade and after the curved Lowsley is clearly visible (Fig. 7.10a) it is replaced with a straight Lowsley passed in the bladder directly through the operative area. The anterior wall of the urethra is then divided similarly over the right angled forceps (Fig. 7.10b). Sutures may be taken in the anterior urethral wall at this time, when it is visible, for subsequent anastomosis. Keeping a downward traction on the straight Lowsley tractor, the anterior surface of the prostate is then bluntly dissected. The puboprostatic ligaments can be identified at this stage (Fig. 7.10c) and they are sharply divided no farther than the level of bladder neck. The DVC gets pushed automatically and does not come into the picture (see Fig. 7.3).

Fig. 7.10

(a) At prostatic apex, with the posterior wall of urethra divided, Lowsley can be seen shining. (b) Anterior wall of urethra ready to be divided. (c) Downward depression on straight Lowsley tractor brings anterior surface in view. PPL puboprostatic ligaments

Defining Bladder Neck and Transection

The above step exposes the anterior bladder neck which can be confirmed by rotating the straight Lowsley to feel its wing through the anterior bladder wall at the bladder neck (Fig. 7.11a). The bladder is opened at this point and the straight Lowsley is then replaced with either a Foley catheter or a penrose drain which enters the prostatic urethra and comes out through this opening to loop and maneuver the prostate during further dissection. A curved scissors is used to transect the anterior bladder neck. A thin Deaver retractor is passed in the bladder through this opening and used to retract the bladder wall to help identify the ureteric orifices before one sharply divides the posterior wall of the bladder (Fig. 7.11b). The Deaver retractor is then shifted to a subtrigonal position in the plane between bladder and seminal vesicles. If not already dissected, the vas and SVs are then dissected and the SV arteries are clipped on either side to deliver the specimen (Fig. 7.12). The rectum is inspected for any inadvertent injury before the anastomosis.

Fig. 7.11

(a) Anterior bladder wall is opened over wing of straight Lowsley felt at bladder neck. (b) Division of the posterior bladder wall after confirming that the orifices are away

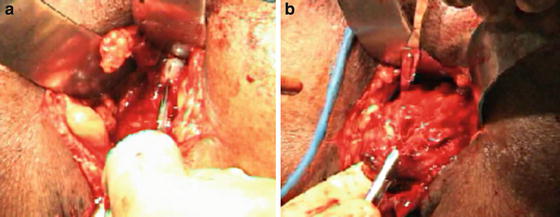

Fig. 7.12

(a) The vas deferens brought out over a right angled forceps. (b) Seminal vesicle (SV) with some pedicular tissue still attached. (It is preferable to dissect SVs prior to opening of the bladder.) (c) The complete specimen after an extrafascial dissection

Vesicourethral Anastomosis

Before the anastomosis, if the bladder opening is wide, the bladder is sutured to itself starting from 6 o’clock till the size of the bladder opening is approximately 30 Fr. This “racquet handle” closure also secures the ureteric orifices in a position away from vesicourethral anastomosis. A 2-0 Monocryl® (poliglecaprone 25) suture on a 5/8 circle needle is used for the anastomosis. Six interrupted stitches over a 3 way 18 Fr catheter are enough for a secure anastomosis. As both the urethral end and the bladder are right in front at the level of the eyes, the anastomosis is relatively easier to perform than in other techniques of radical prostatectomy (Fig. 7.13). A gloved drain or a closed suction drain is placed close to but not directly behind the anastomotic line. Before closure, the fibers of the rectourethralis are sutured to the bulb of the penis and the central tendon is reapproximated. Skin is then closed with nylon sutures or staples.

Fig. 7.13

(a) The urethra (with metal dilator protruding out) and the bladder edges (held in Babcock forceps) are usually right in front and close to each other making vesicourethral anastomosis easier. (b) Completed anastomosis. (c) Sutured incision line with a tube drain coming out separately

Technique of Nerve Sparing

Weldon and Tavel [1] are credited for the description of nerve sparing technique in RPP. Nerve sparing is indicated in men who have good preoperative erectile function and have either T1 disease (bilateral nerve sparing) or T2a disease (unilateral nerve sparing). After mobilization of the lateral surface and base of the prostate, a longitudinal midline incision is given on the ventral rectal fascia on the surface of prostate (posterior layer of Denonvillier’s fascia). The incision can be extended on either side toward the base in an inverted Y fashion if a bilateral nerve sparing is planned. The fascia along with the NVB (the PNB) is lifted away from prostatic surface along the entire length of this incision. Any attachments to the prostatic surface are clipped avoiding electrocautery use. The NVB is mobilized distally up to 1 cm beyond the prostatourethral junction and proximally up to the prostatic base. This allows moving the entire fascial layer laterally (including PNB and ANP) so that it does not get stretched during maneuvering of the prostate. The levator ani is left covered with these fascial layers in a nerve sparing dissection whereas in a non-nerve sparing dissection, the fibers lie bare (Fig. 7.14). If there is induration preventing the release of this fascial layer, ipsilateral nerve excision is performed.